The Fruit Fanatics: Unveiling the World of Frugivores

In the intricate tapestry of Earth’s ecosystems, certain creatures play roles so vital that their absence would unravel entire communities. Among these unsung heroes are frugivores, a fascinating group of animals whose lives revolve around one delicious, often colorful, and incredibly important food source: fruit. Far more than just picky eaters, frugivores are master gardeners of the wild, shaping landscapes and fostering biodiversity with every bite and every dispersed seed.

What Defines a Frugivore?

At its core, a frugivore is an animal whose diet consists primarily of fruit. While many animals might snack on fruit occasionally, true frugivores have evolved specialized adaptations that make them exceptionally efficient at finding, consuming, and processing this unique food source. Their entire biology is often geared towards a fruit-rich lifestyle.

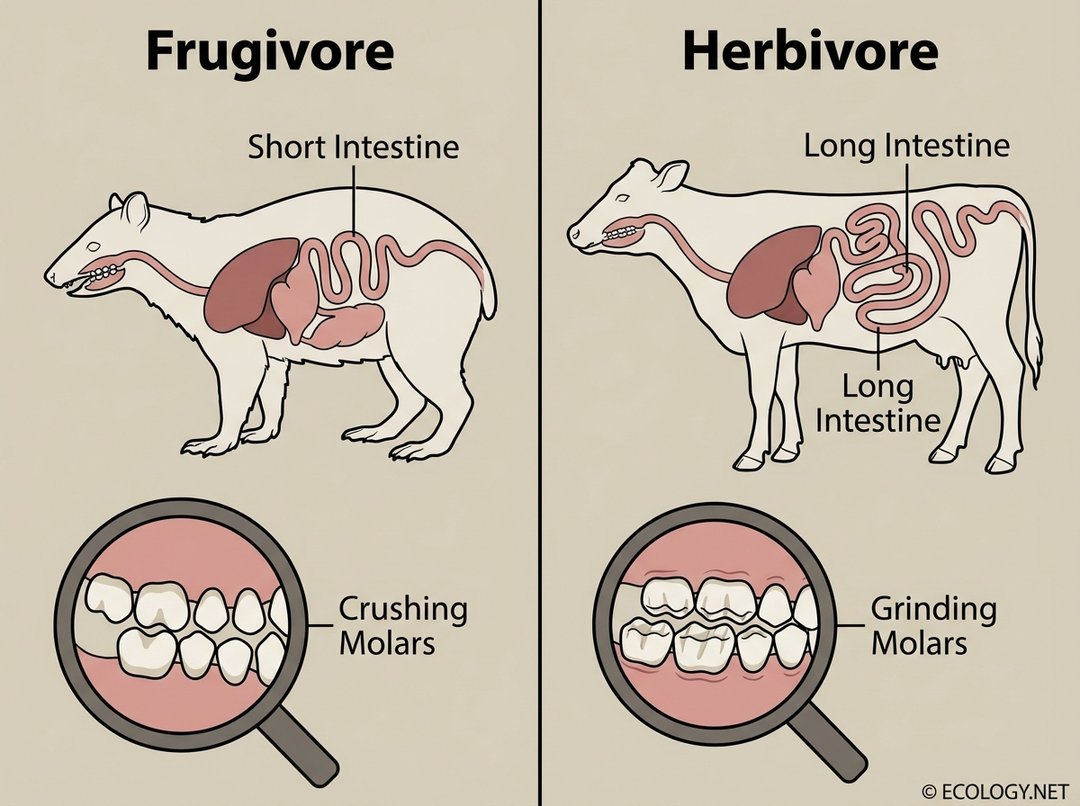

One of the most striking differences between a frugivore and a general herbivore lies in their internal machinery. Frugivores typically possess a relatively short digestive tract. This adaptation allows them to quickly process the easily digestible sugars and carbohydrates found in fruit, minimizing the time spent on less nutritious fibrous material. In contrast, general herbivores, which consume tougher plant matter like leaves and stems, often have long, complex digestive systems designed for extensive fermentation and nutrient extraction.

Their dental structure also tells a compelling story. Frugivores often feature broad, relatively flat molars designed for crushing and mashing soft fruits, rather than the sharp tearing teeth of carnivores or the robust grinding molars of herbivores built for tough vegetation. These specialized teeth allow them to efficiently break down fruit pulp and access the sugary goodness within.

This image visually explains the key physiological and dental adaptations that define a frugivore, making the comparison with a general herbivore clear and easy to understand.

A Diverse Bunch: Examples of Frugivores

The world of frugivores is incredibly diverse, spanning across nearly every animal class and continent. From tiny insects to large mammals, many species have discovered the nutritional benefits of fruit. This wide array of fruit-eaters highlights the success of this dietary strategy and the abundance of fruit in various ecosystems.

Consider some of these remarkable examples:

- Mammals: Primates like spider monkeys, orangutans, and chimpanzees are well-known frugivores, spending much of their day foraging for ripe fruits in tropical forests. Fruit bats, found across tropical and subtropical regions, are nocturnal fruit specialists, playing a crucial role in pollination and seed dispersal. Even some bears, like the spectacled bear, incorporate significant amounts of fruit into their omnivorous diet.

- Birds: Toucans, hornbills, and many species of parrots are iconic avian frugivores, their vibrant colors often mirroring the fruits they consume. These birds are adept at plucking fruits from branches and often have specialized beaks for the task.

- Fish: Less commonly known, but equally fascinating, are frugivorous fish. The pacu fish, native to South American rivers, possesses surprisingly human-like teeth, perfectly adapted for crushing fallen fruits and nuts that drop into the water.

- Reptiles: Some species of tortoises and iguanas also include fruit as a significant part of their diet, particularly in island ecosystems where fruit may be readily available.

This image provides concrete, photo-realistic examples of the wide variety of animals that are frugivores, illustrating the concept and making it more tangible and engaging for the reader.

The Ecological Role of Frugivores: Seed Dispersal

Beyond their intriguing dietary habits, frugivores are indispensable architects of healthy ecosystems. Their most critical ecological contribution is undoubtedly seed dispersal, a process fundamental to plant reproduction and the regeneration of forests and other plant communities. Without frugivores, many plant species would struggle to spread their offspring, leading to reduced biodiversity and ecosystem collapse.

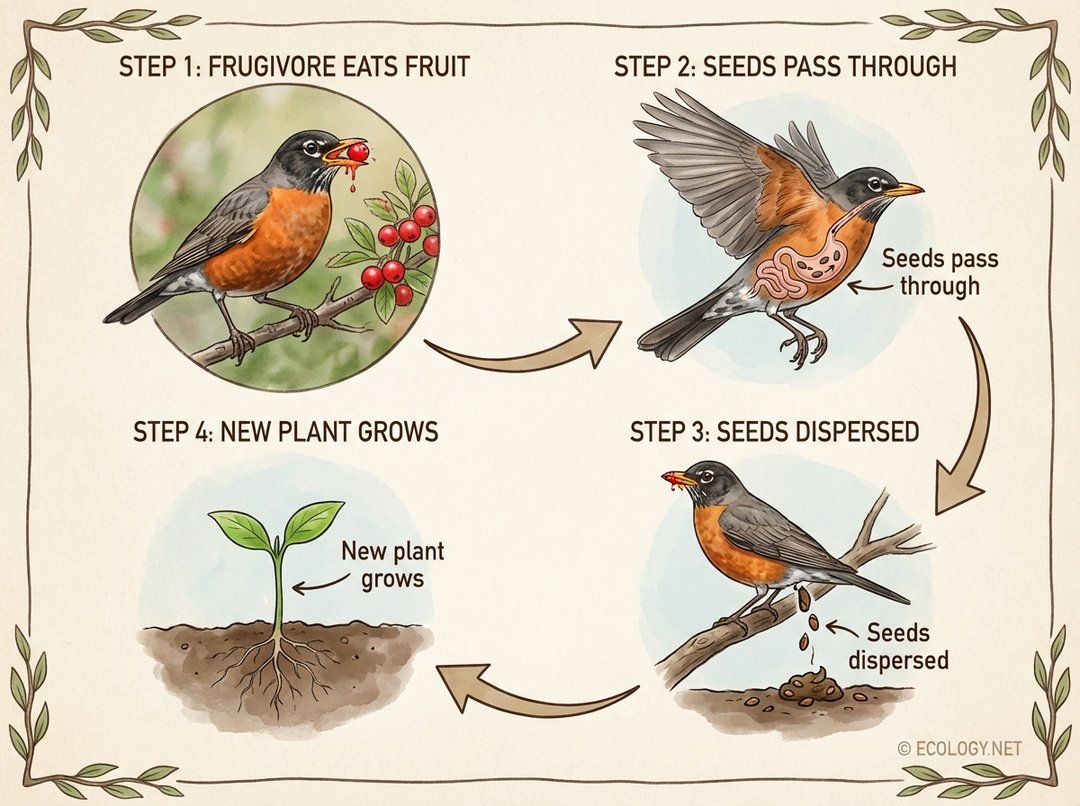

The process of seed dispersal by frugivores is a remarkable example of co-evolution, a biological dance between plants and animals that has unfolded over millions of years. Here is how it typically works:

- Frugivore Eats Fruit: An animal consumes a ripe fruit, attracted by its color, scent, and nutritional content. The fruit’s fleshy pulp is digested, but the seeds, often protected by a hard coat, usually pass through the digestive system unharmed.

- Seeds Pass Through: As the frugivore moves through its habitat, the seeds travel through its gut. This journey can sometimes even aid germination by scarifying the seed coat, making it easier for water to penetrate once deposited.

- Seeds Dispersed: Eventually, the seeds are expelled in the animal’s feces, often far from the parent plant. This dispersal is crucial, as it reduces competition between parent and offspring, allows plants to colonize new areas, and helps avoid pathogen accumulation around the parent plant.

- New Plant Grows: Deposited in a nutrient-rich package of feces, the seeds have a better chance of germinating and growing into new plants, continuing the cycle of life.

This image clearly illustrates the critical ecological role of frugivores in seed dispersal, breaking down the process into easy-to-understand steps, enhancing clarity and engagement.

This symbiotic relationship is a cornerstone of forest dynamics. Many tropical trees, for instance, rely almost entirely on frugivores for their propagation. The loss of these fruit-eating animals can have cascading effects, leading to a decline in tree populations and a reduction in forest health and resilience.

Beyond the Basics: Specialized Frugivory and Nutritional Aspects

While the general definition of a frugivore is straightforward, the reality is far more nuanced. Ecologists often categorize frugivores based on their degree of fruit dependence:

- Obligate Frugivores: These animals rely almost exclusively on fruit for their survival. Their physiology and behavior are highly specialized for a fruit-only diet. Examples include many species of fruit bats and some tropical birds.

- Facultative Frugivores: These animals consume fruit as a significant part of their diet, but also incorporate other food sources like leaves, insects, or nectar. Many primates and bears fall into this category, adapting their diet based on seasonal availability.

The nutritional challenges of a fruit-heavy diet are also fascinating. While fruit is rich in sugars and vitamins, it can be relatively low in protein and certain minerals. Frugivores have evolved various strategies to overcome these limitations:

- Selective Foraging: They often seek out specific fruits that offer a better balance of nutrients, or they might supplement their diet with insects or young leaves to boost protein intake.

- High Consumption: To compensate for lower nutrient density, many frugivores consume vast quantities of fruit, processing large volumes to extract sufficient energy and nutrients.

- Seasonal Shifts: Their diets often shift seasonally, consuming more protein-rich foods when fruit is scarce, or focusing on fruits with higher fat content when available.

The co-evolutionary dance between plants and frugivores is also evident in the fruits themselves. Plants have evolved a dazzling array of colors, scents, and flavors to attract specific dispersers. Some fruits are designed to be eaten quickly and their seeds passed rapidly, while others might have tougher exteriors to withstand a longer journey or specific digestive processes. This intricate relationship underscores the deep interconnectedness of life in ecosystems.

Threats and Conservation

Despite their vital role, frugivores and the ecosystems they support face numerous threats. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to deforestation for agriculture, logging, and urban expansion are primary concerns. When forests are cleared, not only do frugivores lose their homes, but their food sources also disappear, disrupting the entire seed dispersal cycle.

Hunting also poses a significant threat to many larger frugivores, particularly primates and birds, which are often targeted for bushmeat or the pet trade. The decline of these key dispersers can lead to a phenomenon known as “empty forests,” where trees are present but the crucial process of regeneration through seed dispersal is severely hampered.

Conservation efforts for frugivores are intrinsically linked to forest conservation. Protecting and restoring natural habitats, establishing protected areas, and combating illegal hunting are all crucial steps. Understanding the specific dietary needs and dispersal patterns of different frugivore species is also vital for effective conservation strategies. By safeguarding these fruit fanatics, humanity helps to preserve the health and biodiversity of our planet’s most precious ecosystems.

Conclusion

Frugivores, from the smallest fruit fly to the largest ape, are far more than just fruit-eaters. They are essential components of healthy ecosystems, acting as vital links in the chain of life. Their unique adaptations, diverse forms, and indispensable role in seed dispersal highlight the intricate beauty and delicate balance of nature. Recognizing and protecting these incredible creatures is not just about saving a species; it is about preserving the very fabric of the forests and the biodiversity that enriches our world. Their story is a powerful reminder of how interconnected all life truly is, and how the fate of one group of animals can profoundly impact the health of an entire planet.