Imagine a garden that largely takes care of itself, producing an abundance of food, medicine, and useful materials year after year with minimal human intervention. This is not a utopian dream, but a practical reality known as forest gardening. Drawing inspiration from natural woodland ecosystems, forest gardening is a sustainable land management system that mimics the structure and function of a young, natural forest, but with a focus on edible and useful plants.

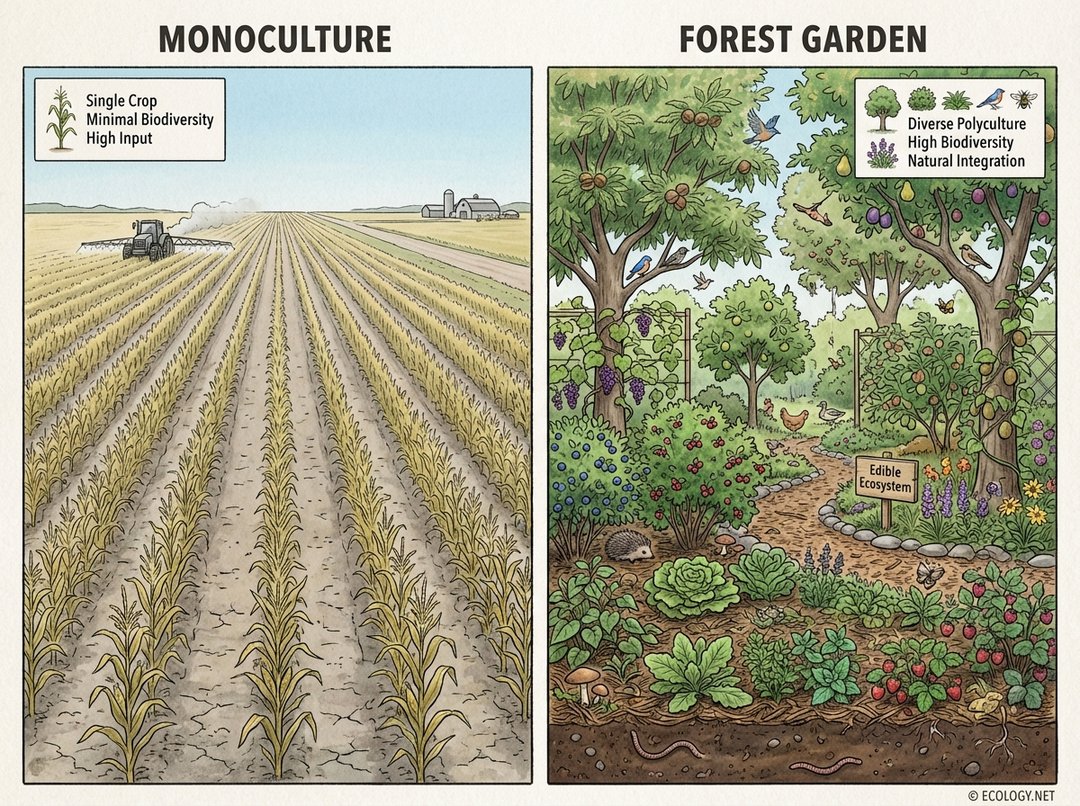

At its heart, forest gardening is about working with nature, not against it. Instead of fighting weeds or constantly tilling soil, practitioners observe natural patterns and design systems that harness ecological processes. This approach stands in stark contrast to conventional agriculture, which often relies on monocultures and external inputs.

The image above powerfully illustrates this fundamental difference. On one side, the vast, uniform expanse of a monoculture field represents a system vulnerable to pests, diseases, and soil degradation, demanding constant human intervention. On the other, the lush, integrated tapestry of a forest garden showcases resilience, biodiversity, and a self-sustaining cycle of growth and renewal. This ecological mimicry is the cornerstone of forest gardening, leading to healthier soil, greater biodiversity, and a more stable food supply.

The Foundational Principles of Forest Gardening

To truly understand forest gardening, it is essential to grasp its core principles. These are the guiding philosophies that differentiate it from traditional gardening or farming:

- Mimicking Natural Ecosystems: The most crucial principle is to observe and emulate the patterns found in nature, particularly those of a forest edge or a young woodland. This means designing for diversity, layering, and natural succession.

- Perennial Focus: Unlike annual crops that require replanting each year, forest gardens prioritize perennial plants. Trees, shrubs, and many herbs and groundcovers return year after year, reducing labor and soil disturbance.

- Biodiversity: A wide variety of plants and animals are encouraged. This diversity creates a robust ecosystem, making the garden more resistant to pests and diseases and enhancing overall productivity.

- Low Maintenance: Once established, a well-designed forest garden requires significantly less work than a conventional garden. The system largely takes care of itself, with plants supporting each other and natural processes handling fertility and pest control.

- Stacking Functions: Every element in a forest garden should ideally serve multiple purposes. For example, a fruit tree provides food, shade, habitat, and contributes to soil health.

- Closed-Loop Systems: The aim is to create a self-sustaining system where waste from one element becomes a resource for another. This minimizes the need for external inputs like fertilizers or pesticides.

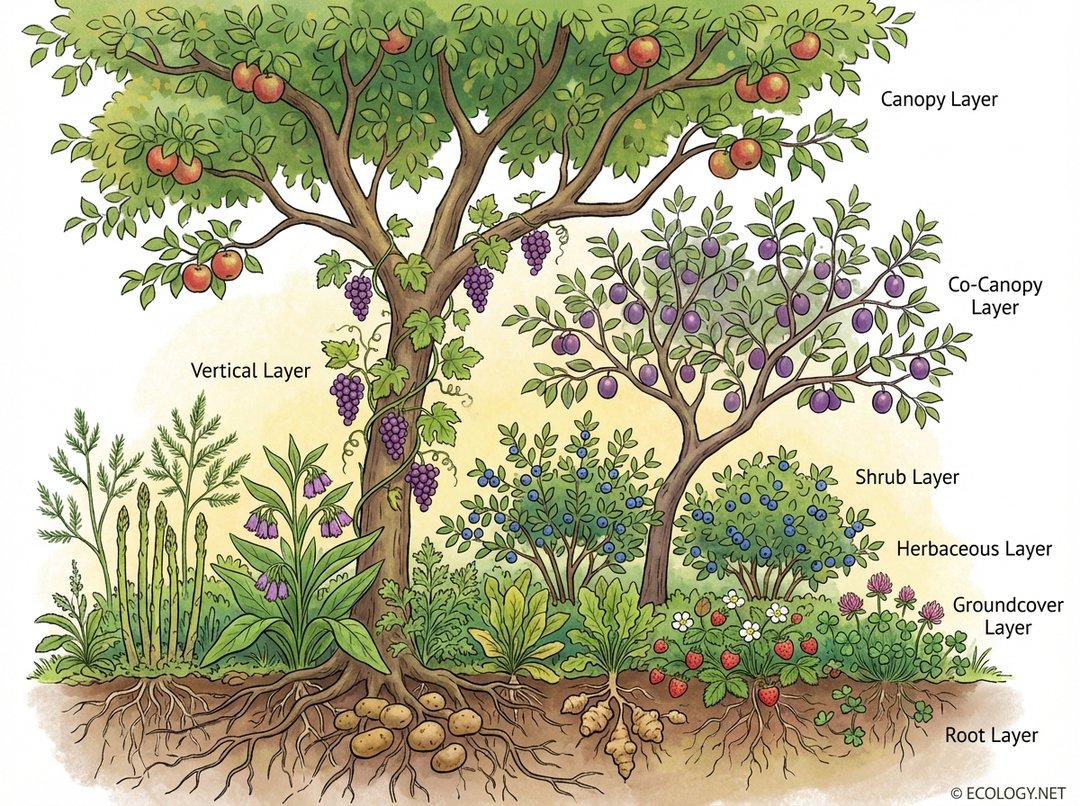

Unveiling the Seven Layers of a Forest Garden

One of the most distinctive and brilliant aspects of forest gardening is its multi-dimensional structure. By utilizing vertical space, a forest garden can produce far more food per square meter than a flat, single-layer garden. This stratification is typically broken down into seven distinct layers, each playing a vital role in the overall ecosystem.

Let us explore each layer, from the towering giants to the hidden treasures beneath the soil:

- Canopy Layer: This is the tallest layer, composed of large fruit and nut trees. These trees provide the overarching structure, create microclimates, and offer a significant yield.

- Examples: Apple trees, pear trees, chestnut trees, pecan trees.

- Co-Canopy (or Understory) Layer: Beneath the canopy, this layer consists of smaller fruit trees and large shrubs that tolerate partial shade. They fill the space below the main canopy, adding to the overall productivity.

- Examples: Plum trees, cherry trees, hazelnut bushes, pawpaw trees.

- Shrub Layer: This layer is made up of berry bushes and other productive shrubs. They thrive in the dappled light and contribute significantly to the edible harvest.

- Examples: Blueberry bushes, raspberry canes, currant bushes, elderberry.

- Vertical (or Climber) Layer: This unique layer utilizes vertical space by growing vines and climbing plants up the trunks and branches of the trees in the canopy and co-canopy layers.

- Examples: Grapes, kiwi vines, climbing beans (annuals, but can be integrated), passionfruit.

- Herbaceous Layer: This layer comprises perennial herbs, vegetables, and flowers that die back to the ground in winter and re-emerge in spring. They are crucial for ground cover, pest deterrence, and attracting beneficial insects.

- Examples: Asparagus, rhubarb, comfrey, mint, oregano, chives, calendula.

- Groundcover Layer: Low-growing plants that spread horizontally, covering the soil and suppressing weeds. They also help retain moisture, prevent erosion, and can provide additional yields.

- Examples: Strawberries, clover, creeping thyme, nasturtiums.

- Root (or Rhizosphere) Layer: The hidden layer beneath the soil surface, consisting of edible root crops and tubers. This layer is vital for soil health, aeration, and provides a unique harvest.

- Examples: Potatoes, Jerusalem artichokes, sunchokes, yacon, groundnuts.

By carefully selecting plants for each of these layers, a forest gardener creates a dense, productive, and resilient ecosystem that maximizes space and resources.

Key Concepts and Techniques for a Thriving Forest Garden

Beyond the layered structure, several other ecological concepts are fundamental to the success of a forest garden. These techniques enhance the garden’s health, productivity, and self-sufficiency.

Guilds and Companion Planting

One of the most powerful strategies in forest gardening is the creation of “guilds” or beneficial plant communities. A guild is a group of plants, often centered around a main productive plant (like a fruit tree), that work together to support each other’s growth and health. This is a sophisticated form of companion planting.

Consider the example of an apple tree guild shown above. Around the central apple tree, various companion plants are strategically placed:

- Comfrey: A dynamic accumulator, its deep taproot brings up nutrients from the subsoil, making them available to other plants when its leaves are chopped and dropped as mulch. It also attracts pollinators.

- Strawberries: A groundcover that suppresses weeds, provides an edible yield, and helps retain soil moisture.

- Chives: A pest repellent, its strong scent can deter common apple pests.

- Clover: A nitrogen fixer, it captures atmospheric nitrogen and converts it into a form usable by plants, enriching the soil naturally.

Other examples of companion planting within guilds include:

- Planting garlic or onions around fruit trees to deter borers.

- Using nasturtiums as a trap crop for aphids, diverting them from more valuable plants.

- Integrating dill or fennel to attract beneficial predatory insects.

Water Management and Soil Health

Water is life, and in a forest garden, efficient water management is paramount. Techniques like mulching are critical. A thick layer of organic mulch (wood chips, straw, leaves) helps retain soil moisture, suppress weeds, regulate soil temperature, and slowly break down to enrich the soil. In some designs, features like “swales” (ditches dug on contour) are used to slow, spread, and sink rainwater into the landscape, preventing runoff and recharging groundwater.

Soil health is the foundation of a productive forest garden. By avoiding tilling, adding organic matter, and fostering a diverse microbial community, the soil becomes a living, breathing ecosystem. Nitrogen-fixing plants (like clover, peas, beans, and certain trees like alders) are invaluable for naturally enriching the soil with nitrogen, reducing the need for external fertilizers.

Succession and Resilience

Forest gardens are designed with an understanding of ecological succession, the natural process by which ecosystems change over time. While a young forest garden might have more open spaces and annuals, it gradually transitions towards a more mature, self-sustaining system dominated by perennials. This long-term perspective builds resilience, allowing the garden to adapt to changing conditions and recover from disturbances.

Designing Your Own Forest Garden

Embarking on the journey of creating a forest garden can seem daunting, but it can be approached systematically. Here are some steps to consider:

- Site Analysis: Understand your land.

- Observe sun patterns throughout the day and year.

- Identify existing vegetation, soil type, and drainage.

- Note prevailing winds and microclimates.

- Define Your Needs and Desires: What do you want to harvest? Food, medicine, timber, animal fodder? How much time can you commit?

- Design on Paper: Sketch out your ideas.

- Map out the canopy layer first, as these trees will largely define the garden’s structure.

- Then, fill in the understory, shrub, and herbaceous layers, considering light requirements and companion planting.

- Don’t forget paths and access points.

- Plant Selection: Choose plants suitable for your climate and soil, focusing on perennials with multiple uses. Prioritize native species where possible, as they are often well-adapted to local conditions.

- Start Small: You do not need to convert your entire property at once. Begin with a small section or even a single guild around an existing tree. Learn from your experiences and expand gradually.

- Observe and Adapt: Nature is dynamic. Continuously observe how your plants are growing, how the ecosystem is developing, and be prepared to make adjustments.

The Profound Benefits of Forest Gardening

The advantages of adopting a forest gardening approach extend far beyond simply growing food. It offers a holistic solution to many contemporary challenges.

Environmental Benefits

- Enhanced Biodiversity: By creating diverse habitats, forest gardens attract a wide array of insects, birds, and other wildlife, contributing to local ecosystem health.

- Soil Regeneration: Perennial plants, minimal soil disturbance, and constant organic matter input lead to healthier, more fertile soil, rich in microbial life.

- Water Conservation: The dense canopy, groundcover, and mulching layers significantly reduce water evaporation and runoff.

- Carbon Sequestration: Trees and perennial plants store carbon in their biomass and in the soil, helping to mitigate climate change.

- Reduced Pollution: Eliminates the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, protecting waterways and beneficial organisms.

Economic and Social Benefits

- Increased Food Security: Provides a stable, diverse, and abundant food supply that is resilient to many environmental challenges.

- Reduced Inputs: Once established, the need for external inputs like fertilizers, pesticides, and even irrigation is greatly diminished, saving money and resources.

- Long-Term Productivity: Perennial systems yield year after year, often increasing in productivity as they mature.

- Community Building: Forest gardens can be excellent community projects, fostering shared knowledge and local food systems.

- Educational Value: They serve as living classrooms, demonstrating ecological principles in action.

Personal Benefits

- Improved Health: Access to fresh, organic, nutrient-dense food.

- Reduced Labor: Over time, the garden becomes less demanding, freeing up time and energy.

- Connection to Nature: Fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation for natural systems.

- Aesthetic Appeal: A well-designed forest garden is a beautiful, lush, and tranquil space.

Challenges and Considerations

While the benefits are compelling, it is also important to acknowledge potential challenges:

- Initial Setup Time and Effort: Establishing a forest garden requires careful planning and a significant upfront investment of time and labor, especially in preparing the site and planting the initial layers.

- Patience: Unlike annual vegetable gardens that yield quickly, many elements of a forest garden, particularly the trees, take several years to mature and become highly productive.

- Space Requirements: While possible on a small scale, a truly diverse and productive forest garden often benefits from more space than a typical backyard vegetable patch.

- Knowledge Curve: Understanding plant interactions, succession, and ecological design requires learning and observation.

Embracing a Greener Future

Forest gardening represents a profound shift in how humanity can interact with the land. It moves beyond mere sustainability towards a regenerative approach, actively healing and enhancing ecosystems while providing for human needs. It is a testament to the power of observation, ecological understanding, and patient design.

As the world grapples with climate change, biodiversity loss, and food insecurity, the principles and practices of forest gardening offer a beacon of hope. By cultivating edible landscapes that mimic nature’s wisdom, individuals and communities can contribute to a more resilient, abundant, and harmonious future. It is an invitation to participate in a living, breathing ecosystem, to learn from it, and to harvest its generous bounty for generations to come.