Life on Earth is an intricate dance of energy. From the smallest microbe to the largest whale, every organism plays a role in a grand, interconnected system of give and take. At the heart of this system lies a fundamental concept: the food chain. Far from being a simple linear sequence, food chains are the building blocks of complex food webs, dictating the flow of energy and the very structure of ecosystems.

The Basics: What is a Food Chain?

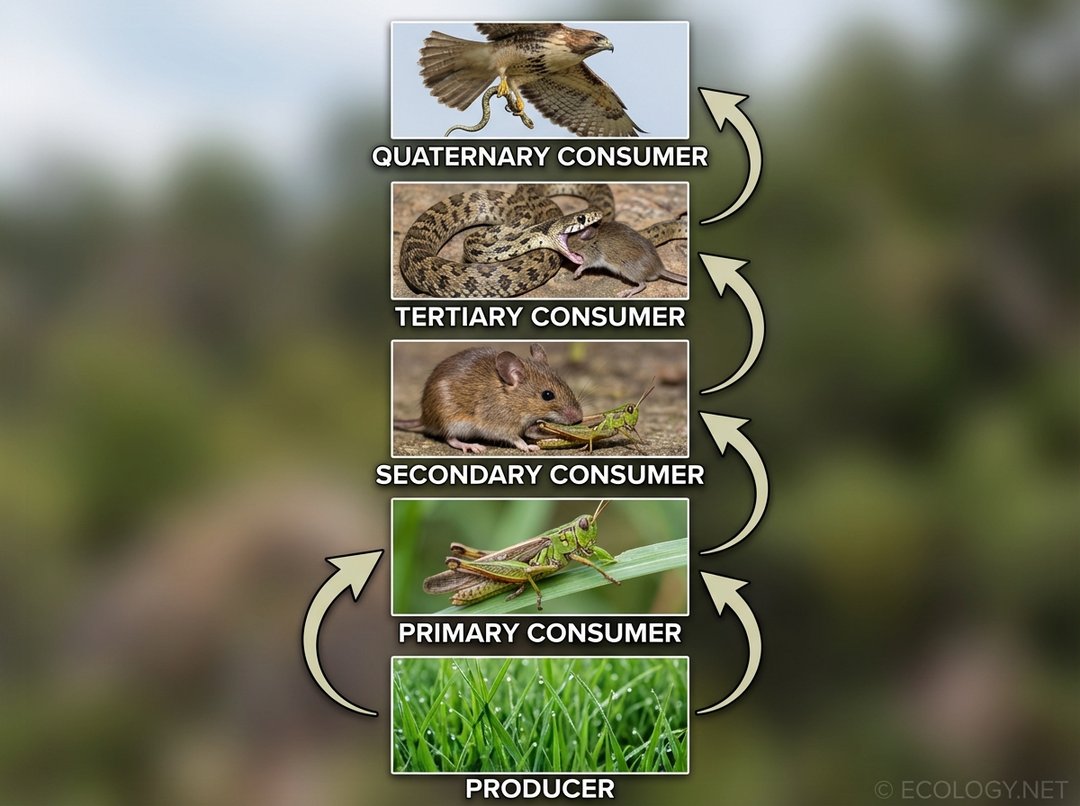

At its core, a food chain describes a single pathway of energy flow in an ecosystem. It illustrates who eats whom, tracing the journey of energy from its initial source through a series of organisms. Think of it as a direct line, showing how nutrients and energy are transferred from one living thing to another.

Every food chain begins with the sun, the ultimate energy source for almost all life on Earth. This solar energy is captured by organisms known as producers.

- Producers: These are organisms, primarily plants and algae, that create their own food through photosynthesis. They convert sunlight into chemical energy, forming the base of nearly every food chain. Without producers, no other life forms could exist.

Following the producers are the consumers, organisms that obtain energy by eating other organisms. Consumers are categorized by what they eat and their position in the chain:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These organisms feed directly on producers. Examples include deer grazing on grass, rabbits eating clover, or insects munching on leaves.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): These organisms eat primary consumers. A fox eating a rabbit, a snake eating a mouse, or a bird eating an insect are all examples of secondary consumption.

- Tertiary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): These organisms feed on secondary consumers. A hawk preying on a snake, or a larger fish eating a smaller fish, fits this category.

- Quaternary Consumers: In some longer food chains, there might be a fourth level of consumers that prey on tertiary consumers. A large apex predator might occupy this role.

This image would illustrate the fundamental concept of a food chain, showing the linear flow of energy through specific organisms and clearly defining the different trophic levels (producers, primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary consumers) as introduced in the ‘The Basics: What is a Food Chain?’ section.

Beyond the Line: Understanding Food Webs

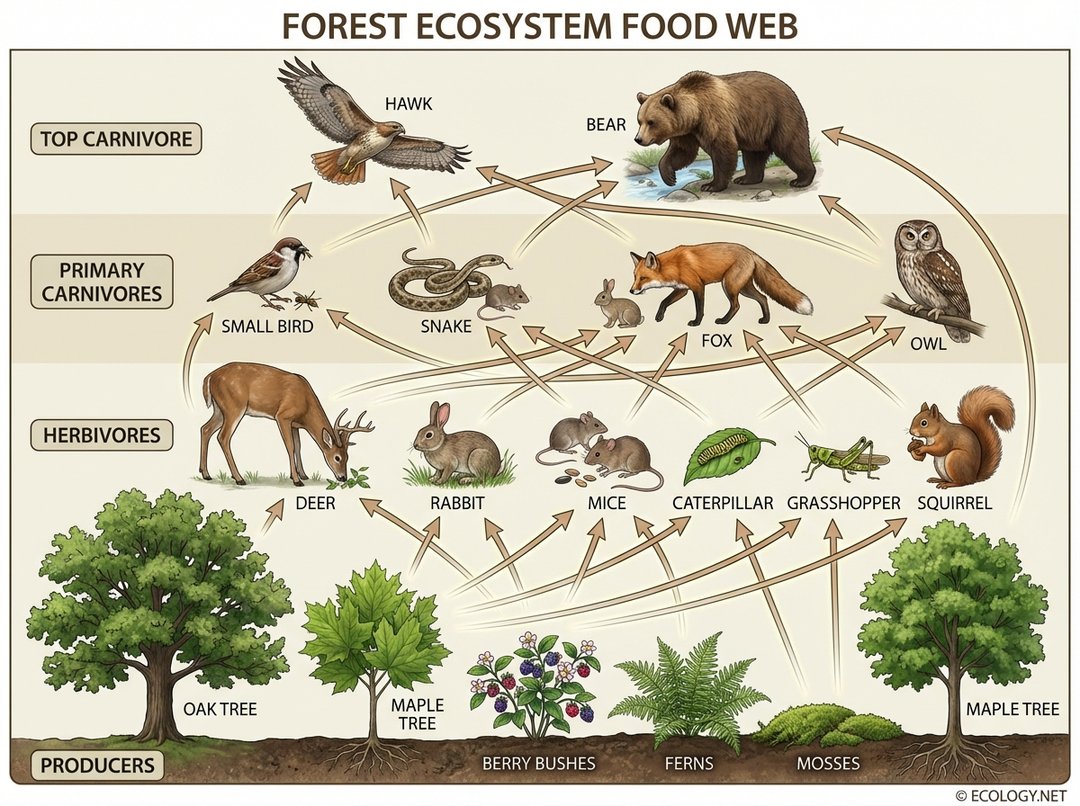

While a food chain provides a clear, linear path, it is often an oversimplification of reality. In most ecosystems, organisms do not rely on just one type of food. A mouse might eat seeds, insects, and berries. A hawk might eat mice, snakes, and small birds. This complex reality leads us to the concept of a food web.

A food web is essentially a collection of interconnected food chains within an ecosystem. It illustrates how multiple food chains intertwine, showing that most organisms have several food sources and are themselves food for multiple predators. This intricate network of feeding relationships provides a much more accurate picture of energy flow and ecological interactions.

Why are Food Webs Important?

- Stability: Food webs contribute significantly to the stability of an ecosystem. If one food source for an animal becomes scarce, it can often switch to another, preventing a collapse of its population. This redundancy makes the ecosystem more resilient to disturbances.

- Biodiversity: The complexity of a food web often reflects the biodiversity of an ecosystem. A greater variety of species typically leads to a more intricate and robust food web.

- Interconnectedness: Food webs highlight the profound interconnectedness of all living things. A change in one population, whether an increase or decrease, can have ripple effects throughout the entire web, impacting many other species.

This illustration would visually represent the concept of a ‘Food Web’ as described in the article, highlighting how organisms typically have multiple food sources and are part of a complex, interwoven network of food chains, rather than simple linear sequences.

The Engine of Life: Energy Transfer and Ecological Efficiency

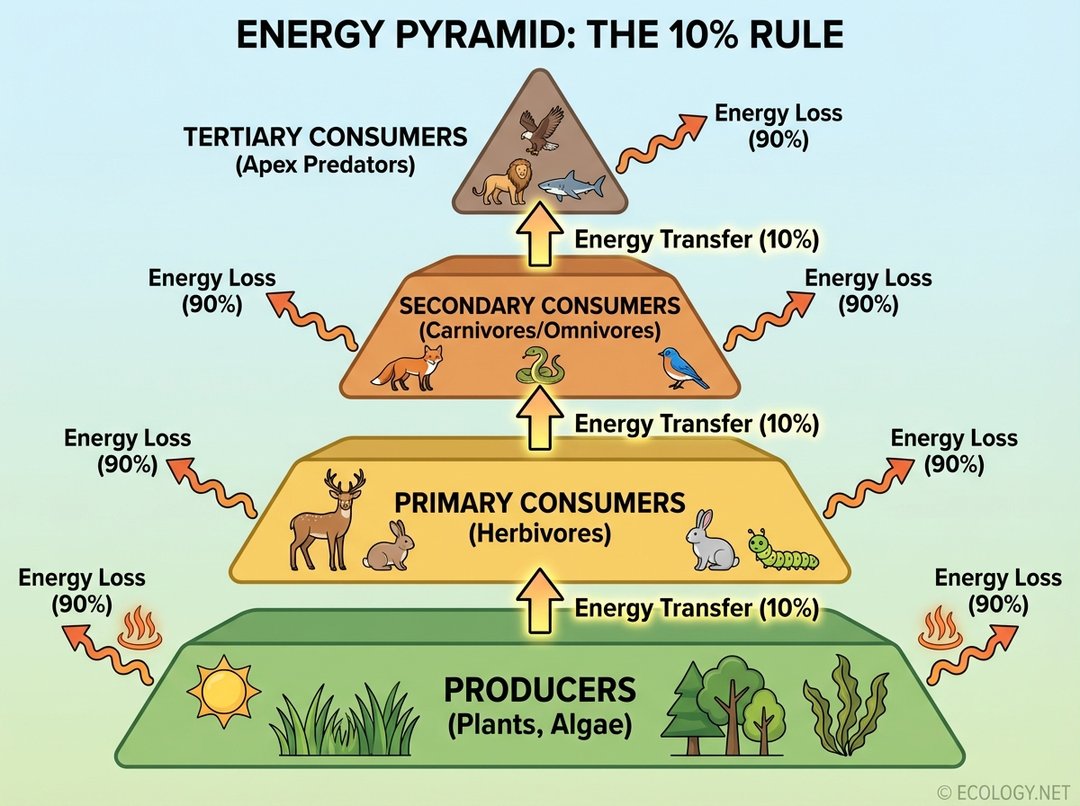

Energy is the driving force behind all life, and its transfer through food chains and webs is not a perfectly efficient process. When one organism consumes another, only a fraction of the energy from the consumed organism is transferred to the consumer. The rest is lost, primarily as heat, during metabolic processes, or remains in uneaten or undigested parts.

The 10% Rule

A widely accepted principle in ecology is the “10% Rule” of energy transfer. This rule states that, on average, only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next trophic level. The remaining 90% is lost to the environment or used for the organism’s own life processes (respiration, movement, reproduction) before it can be consumed.

Consider the implications of this rule:

- If producers capture 10,000 units of energy, primary consumers will only assimilate about 1,000 units.

- Secondary consumers will then only get about 100 units from the primary consumers.

- Tertiary consumers will receive a mere 10 units.

This dramatic reduction in available energy explains several key ecological phenomena:

- Pyramid Structure: Ecosystems typically have a pyramid structure, with a large base of producers supporting progressively smaller populations of consumers at higher trophic levels. There are always more plants than herbivores, and more herbivores than carnivores.

- Limited Trophic Levels: Most food chains rarely extend beyond four or five trophic levels because there simply isn’t enough energy left to support a higher level of consumers.

- Biomass Distribution: The total biomass (the total mass of living organisms) also decreases significantly at each successive trophic level.

This image would effectively explain the ‘Energy Transfer and Ecological Efficiency’ section, visually demonstrating the ‘10% rule’ and why there are fewer organisms at higher trophic levels due to significant energy loss at each step of the food chain.

Types of Food Chains

While the general principles apply, food chains can be broadly categorized into two main types based on their starting point:

Grazing Food Chains

These are the most commonly depicted food chains, starting with producers that photosynthesize. Energy flows from plants to herbivores (grazers) and then to carnivores. Examples include:

- Grass → Zebra → Lion

- Algae → Zooplankton → Small Fish → Large Fish

Detrital Food Chains

These food chains begin with dead organic matter, known as detritus. Decomposers, such as bacteria and fungi, break down this detritus, releasing nutrients back into the ecosystem and serving as a food source for detritivores (e.g., earthworms, millipedes, some insects). Energy then flows from detritivores to their predators.

- Dead Leaves → Earthworm → Robin

- Dead Wood → Fungi → Beetle Larvae → Shrew

Detrital food chains are incredibly important for nutrient cycling and are often overlooked, yet they process a vast amount of organic material, ensuring that valuable nutrients are not locked away but are instead made available for new life.

The Importance of Food Chains and Webs in Ecosystems

Understanding food chains and webs is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for comprehending the health and functioning of our planet’s ecosystems. They are the circulatory system of nature, moving energy and nutrients and maintaining ecological balance.

- Population Control: Predators keep herbivore populations in check, preventing overgrazing and allowing plant communities to thrive. Conversely, the availability of food sources limits predator populations.

- Nutrient Cycling: While food chains focus on energy, they are intrinsically linked to nutrient cycling. Decomposers, particularly in detrital food chains, play a vital role in breaking down organic matter and returning essential nutrients to the soil or water, making them available for producers once again.

- Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification: Food chains also illustrate how certain substances, particularly toxins and pollutants, can accumulate in organisms (bioaccumulation) and become more concentrated at higher trophic levels (biomagnification). This is why apex predators often carry the highest burdens of environmental contaminants.

- Conservation: Disruptions to food webs, such as the removal of a key species or the introduction of an invasive one, can have cascading effects throughout an ecosystem. Conservation efforts often focus on protecting entire food webs, recognizing the interconnectedness of all species.

Conclusion

From the simplest blade of grass harnessing the sun’s energy to the apex predator at the top of the food web, every organism plays a vital role in the grand tapestry of life. Food chains and webs are not just diagrams in a textbook; they are the dynamic, living networks that sustain all ecosystems, including our own. By understanding these fundamental ecological principles, we gain a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance of nature and our responsibility to protect the intricate connections that make life on Earth possible.