In the intricate tapestry of life, where every creature plays a unique role, some animals have carved out a highly specialized niche: the consumption of leaves. These fascinating organisms, known as folivores, are masters of a diet that, at first glance, seems simple, yet presents a myriad of complex challenges. From the towering rainforest canopies to the arid scrublands, folivores demonstrate remarkable evolutionary ingenuity, shaping ecosystems and influencing the very plants they depend upon.

What Defines a Folivore?

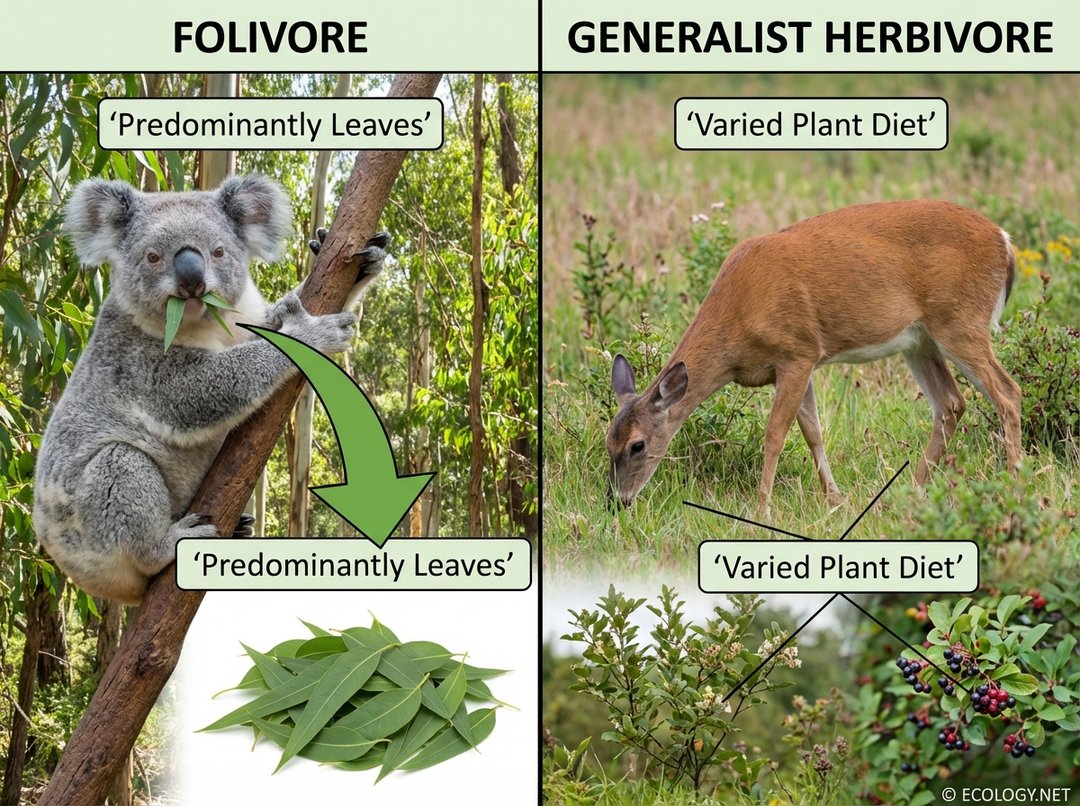

At its core, a folivore is an herbivore whose diet consists primarily of leaves. While many herbivores might occasionally munch on a leaf or two, true folivores have evolved to subsist almost exclusively on this specific plant part. This specialization sets them apart from generalist herbivores, which consume a wide variety of plant materials including fruits, seeds, stems, and roots.

Consider the iconic koala, a quintessential folivore. Its diet is almost entirely restricted to the leaves of eucalyptus trees. In stark contrast, a deer, while certainly an herbivore, browses on leaves, twigs, fruits, and grasses, making it a generalist. This distinction is crucial for understanding the unique biological and ecological pressures folivores face.

The Nutritional Paradox of Leaves

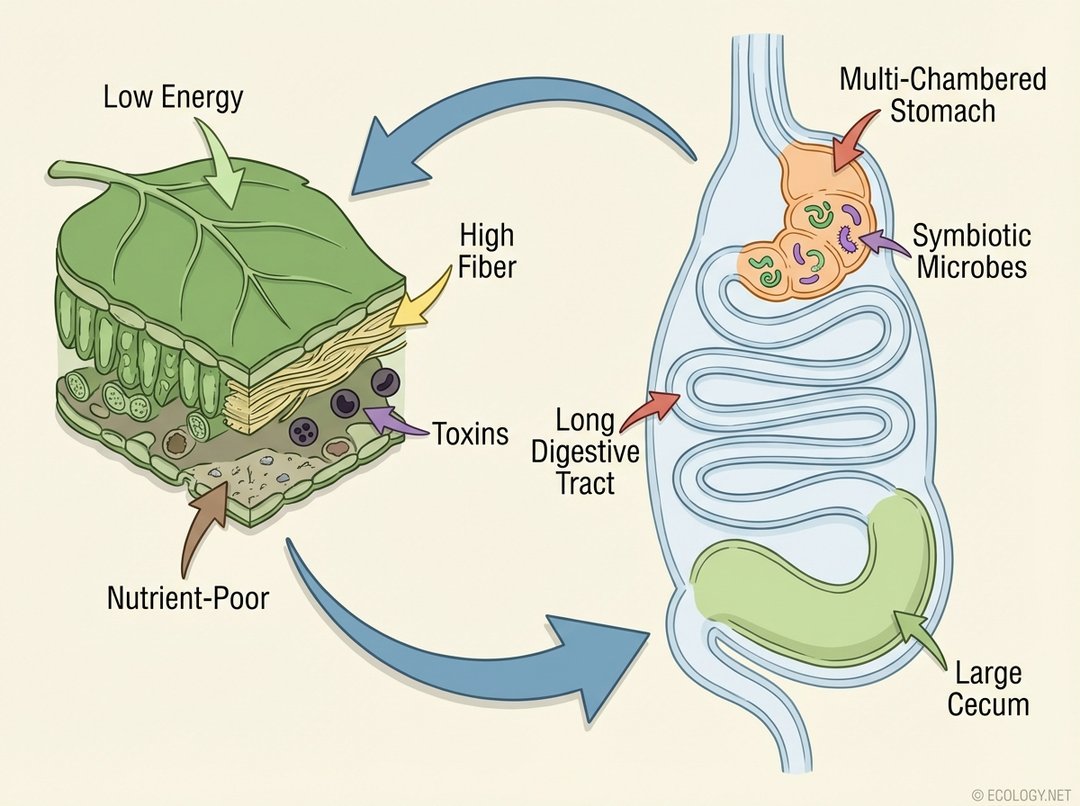

Leaves, despite their abundance, are not an easy food source. They present a significant nutritional paradox for any animal attempting to live off them. Here are some of the primary challenges:

- Low Energy Content: Leaves are generally low in calories and readily digestible nutrients compared to fruits or seeds. Much of their bulk is structural fiber.

- High Fiber Content: Cellulose and lignin, the primary components of plant cell walls, are difficult to break down and extract nutrients from.

- Presence of Toxins: Plants have evolved a vast arsenal of chemical defenses to deter herbivores. Many leaves contain secondary metabolites, such as tannins, alkaloids, and terpenes, which can be toxic or reduce nutrient absorption.

- Nutrient Imbalance: Leaves can be deficient in certain essential minerals or amino acids, requiring folivores to consume large quantities or seek out specific plant species.

Evolutionary Ingenuity: Adaptations for a Leafy Life

To overcome the formidable challenges of a leaf-based diet, folivores have developed an astonishing array of adaptations, both physiological and behavioral. These specializations allow them to extract maximum nutrition from a difficult food source while neutralizing its harmful components.

Digestive System Marvels

The most significant adaptations are found within the digestive system:

- Long Digestive Tracts: Folivores often possess exceptionally long digestive tracts, providing more time for food to be processed and nutrients absorbed.

- Specialized Stomachs: Many folivores, particularly ruminants like cattle (though primarily grazers, they consume leaves), have multi-chambered stomachs. These chambers, especially the rumen, house vast communities of symbiotic microbes.

- Symbiotic Microbes: Bacteria, fungi, and protozoa residing in the gut are the true heroes of folivory. These microorganisms produce enzymes that can break down cellulose and other complex plant fibers, releasing digestible sugars and fatty acids that the host animal can then absorb. This process is often referred to as fermentation.

- Large Cecum: In animals like koalas and sloths, which are hindgut fermenters, a greatly enlarged cecum (a pouch at the beginning of the large intestine) serves as the primary fermentation chamber.

- Coprophagy: Some folivores, such as rabbits, practice coprophagy, re-ingesting their own feces to extract additional nutrients from partially digested plant matter that has undergone a second pass through the digestive system.

Beyond Digestion: Other Adaptations

- Detoxification Mechanisms: Folivores have evolved specialized liver enzymes and other metabolic pathways to neutralize or excrete plant toxins. This often involves a trade-off, as detoxifying can be energetically costly.

- Slow Metabolism: Many folivores, like sloths, exhibit remarkably slow metabolic rates. This allows them to conserve energy when their diet provides limited calories and to spend more time digesting their food.

- Selective Feeding: Folivores often exhibit sophisticated feeding behaviors. They might select younger, more tender leaves which are less fibrous and contain fewer toxins, or they might rotate between different plant species to avoid accumulating high levels of specific toxins. Some even use their sense of smell to detect less toxic leaves.

- Dental Adaptations: Strong, broad molars with ridged surfaces are common among folivores, designed for grinding tough plant material.

A World of Leaf-Eaters: Diverse Examples

Folivory is a strategy found across the animal kingdom, showcasing convergent evolution in response to similar dietary pressures.

- Mammals:

- Koalas: Famous for their eucalyptus-only diet, they have a very long cecum and slow metabolism.

- Sloths: Their extremely slow movement is directly linked to their low-energy leaf diet and slow digestion.

- Howler Monkeys: These New World primates are primarily folivorous, using their specialized digestive systems to process large quantities of leaves.

- Gorillas: While they also eat fruits and stems, leaves form a significant portion of their diet, particularly for mountain gorillas.

- Giant Pandas: Though carnivores by lineage, pandas have adapted to a bamboo-heavy diet, which is essentially a form of folivory due to the high fiber and low nutrient content of bamboo leaves and shoots.

- Insects:

- Caterpillars: The larval stage of butterflies and moths are voracious leaf-eaters, often highly specialized to specific host plants.

- Leaf Beetles: Many species feed exclusively on leaves, sometimes causing significant damage to plants.

- Leaf-cutter Ants: These ants don’t eat the leaves directly but cultivate fungi on them, which they then consume. This is a unique form of indirect folivory.

- Reptiles:

- Green Iguanas: As adults, these lizards are primarily folivorous, consuming a wide range of leaves and flowers.

Ecological Roles of Folivores

Far from being mere consumers, folivores play critical roles in shaping the ecosystems they inhabit. Their feeding habits have cascading effects throughout the food web and nutrient cycles.

Influencing Plant Communities

- Plant Population Control: By consuming leaves, folivores can regulate the growth and population size of certain plant species. This can prevent dominant species from outcompeting others, thereby promoting overall plant diversity.

- Seed Dispersal (Indirect): While not direct seed dispersers like frugivores, folivores can indirectly influence plant distribution by creating gaps in vegetation or altering light conditions, allowing new seedlings to establish.

- Stimulating Plant Growth: Moderate defoliation can sometimes stimulate compensatory growth in plants, leading to increased productivity.

Nutrient Cycling

Folivores are vital intermediaries in nutrient cycling. They convert plant biomass, which is often indigestible to many other organisms, into forms that can be re-integrated into the ecosystem:

- Decomposition: Their waste products (feces) are rich in partially digested organic matter and nutrients. These are readily broken down by decomposers, returning essential elements like nitrogen and phosphorus to the soil, where they become available for new plant growth.

- Energy Transfer: By consuming leaves, folivores transfer energy from the primary producers (plants) to higher trophic levels in the food web.

Food Web Dynamics

As a significant component of herbivore biomass in many ecosystems, folivores serve as a crucial food source for a variety of predators. For example, sloths are prey for jaguars and harpy eagles, while countless insects that feed on leaves become meals for birds, reptiles, and other invertebrates. This linkage is fundamental to maintaining the balance and stability of ecological communities.

Conservation Concerns

Due to their highly specialized diets, many folivores are particularly vulnerable to habitat loss and environmental change. The destruction of specific plant species they depend upon, or alterations to their habitat that impact food availability, can have devastating consequences for these unique animals. Protecting folivores often means protecting the specific plant communities they call home.

Conclusion

Folivores are more than just animals that eat leaves; they are living testaments to the power of evolution, demonstrating incredible adaptations to thrive on a challenging diet. From their complex digestive systems to their crucial roles in nutrient cycling and food web dynamics, these specialized herbivores are indispensable components of Earth’s biodiversity. Understanding folivores not only deepens our appreciation for the natural world but also highlights the intricate connections that sustain life on our planet.