Unpacking Ecological Fitness: Beyond Brawn and Beauty

When the word “fitness” comes to mind, many envision a powerful athlete, a chiseled physique, or perhaps a creature of immense strength and speed. We often associate fitness with survival of the fittest in a literal, physical sense. However, in the realm of ecology and evolutionary biology, the definition of fitness takes a fascinating and profoundly different turn. Here, fitness is not about how strong an individual is, but rather how successful it is at passing its genes to the next generation. It is a measure of reproductive success, the ultimate currency of evolution.

Imagine a magnificent male lion, the king of the savanna, powerful and awe inspiring. Yet, if this lion is sterile and cannot produce offspring, its ecological fitness is zero. Contrast this with a tiny, unassuming fish that lays thousands of eggs, many of which hatch and grow into reproductive adults. Despite its physical vulnerability, this fish possesses extremely high ecological fitness because it successfully perpetuates its genetic lineage. This fundamental distinction is crucial to understanding how life evolves and adapts.

The Core Concept: Reproductive Success

At its heart, ecological fitness is the ability of an organism to survive and reproduce in its environment, thereby contributing its genes to the gene pool of the next generation. It is a relative measure, meaning an individual’s fitness is often compared to the fitness of other individuals within the same population. The more viable offspring an individual produces that themselves survive to reproduce, the higher its fitness.

This concept is the driving force behind natural selection. Traits that enhance an individual’s reproductive success tend to become more common in a population over time, simply because individuals with those traits leave more descendants. Conversely, traits that hinder reproductive success tend to diminish.

Components of Ecological Fitness: A Balancing Act

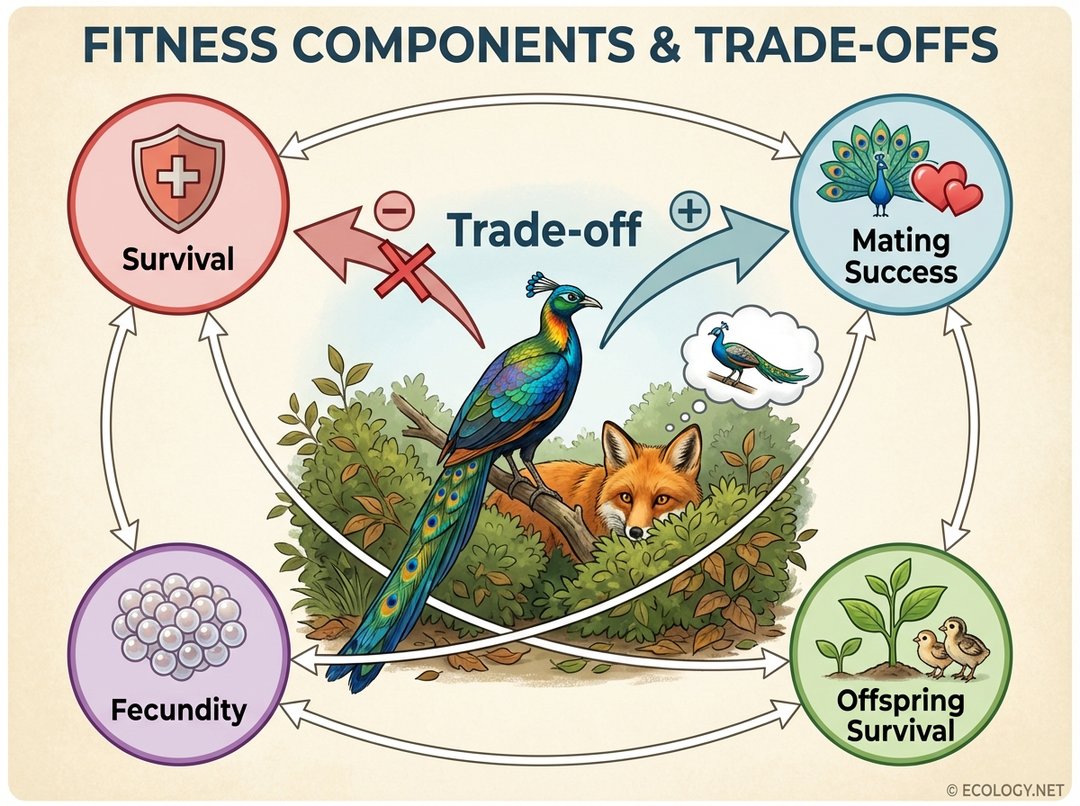

Ecological fitness is not a single, monolithic trait. Instead, it is a complex outcome influenced by several interconnected components. These components often involve evolutionary trade offs, where an improvement in one aspect might come at the expense of another.

The primary components of fitness include:

- Survival: An organism must survive long enough to reproduce. This includes avoiding predators, resisting disease, finding food, and enduring environmental challenges. However, simply surviving is not enough if reproduction does not occur.

- Mating Success: For sexually reproducing organisms, finding a mate and successfully reproducing is paramount. This can involve elaborate courtship rituals, competition for mates, or displaying attractive traits. For example, a peacock’s magnificent tail helps attract mates but also makes it more conspicuous to predators, a classic trade off.

- Fecundity: This refers to the number of offspring an individual produces. Species vary widely in their fecundity, from a single offspring per lifetime to thousands. High fecundity can compensate for low offspring survival rates.

- Offspring Survival: It is not enough to simply produce offspring; those offspring must also survive to reproductive age themselves. Parental care, provisioning of resources, and protection from predators all contribute to offspring survival.

Consider the example of a brightly colored bird. Its vibrant plumage might significantly increase its mating success, making it highly attractive to potential partners. This boosts its fitness through the “Mating Success” component. However, this same bright plumage could also make the bird more visible to predators, thereby reducing its “Survival” component. This illustrates a classic evolutionary trade off, where different components of fitness are balanced against each other to achieve the highest overall reproductive success in a given environment.

Measuring Fitness: A Relative Game

In practice, ecologists often measure relative fitness. This involves comparing the reproductive success of individuals with different traits or genotypes within a population. For instance, if individuals with a particular gene variant produce, on average, 10 offspring that survive to reproduce, while individuals with another variant produce only 5, the first variant has twice the relative fitness of the second. This relative measure is what drives evolutionary change.

The Fitness Landscape: Navigating Evolutionary Peaks and Valleys

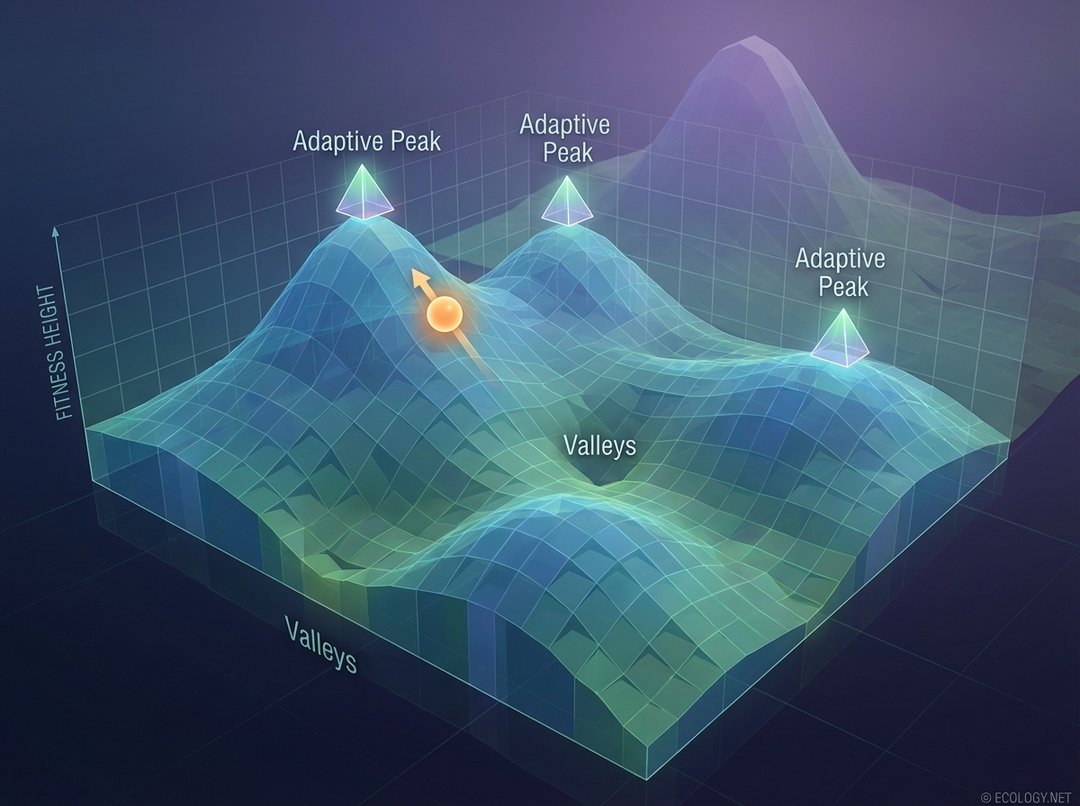

To visualize the complex interplay of traits and fitness, evolutionary biologists often use the concept of a “fitness landscape.” Imagine a three dimensional map where the horizontal axes represent different combinations of traits (e.g., body size and coloration), and the vertical axis represents the fitness associated with those trait combinations. This creates a landscape of hills and valleys.

In this landscape:

- Adaptive Peaks: These are the high points on the landscape, representing combinations of traits that confer high fitness. Natural selection tends to push populations towards these peaks.

- Valleys: These are low points, representing trait combinations that result in low fitness. Organisms with these traits are less likely to survive and reproduce.

A population evolves by “climbing” the slopes of this landscape, moving towards higher fitness. However, a population might become “stuck” on a local adaptive peak, even if a higher, global adaptive peak exists elsewhere on the landscape. This is because moving from a local peak to a higher peak might require passing through a “valley” of lower fitness, which natural selection generally resists. This concept helps explain why some organisms might not possess what appears to be the “perfect” set of traits, but rather a very good, locally optimized set.

Factors Influencing Fitness

Many factors contribute to an organism’s fitness:

- Genetics: The genes an individual inherits determine its potential traits and capabilities.

- Environment: The specific conditions of the habitat, including climate, resource availability, and the presence of predators or competitors, profoundly influence which traits are advantageous. A trait that confers high fitness in one environment might be detrimental in another.

- Behavior: An organism’s actions, such as foraging strategies, mating rituals, or parental care, can significantly impact its survival and reproductive success.

Why Understanding Fitness Matters

The concept of ecological fitness is foundational to all of evolutionary biology. It helps us understand:

- Adaptation: How organisms become so remarkably suited to their environments.

- Biodiversity: The incredible variety of life on Earth, as different species find unique ways to maximize their fitness.

- Conservation: How human activities impact the fitness of populations, informing strategies to protect endangered species and ecosystems.

- Human Health: Evolutionary medicine applies fitness principles to understand the origins of diseases and develop more effective treatments.

Conclusion

Ecological fitness, far from being a simple measure of physical prowess, is a sophisticated concept that underpins the very fabric of life. It is the relentless drive for reproductive success, a complex interplay of survival, mating, fecundity, and offspring viability, all shaped by the environment. By shifting our perspective from individual strength to genetic legacy, we gain a profound appreciation for the intricate mechanisms that have sculpted every living thing on our planet, from the smallest microbe to the largest whale. Understanding fitness is not just an academic exercise; it is a key to unlocking the secrets of evolution and appreciating the dynamic, ever changing tapestry of life.