In the intricate tapestry of nature, some of the most dynamic and biologically rich areas are not found in the heart of vast forests or expansive grasslands, but precisely where these distinct ecosystems meet. These fascinating zones, known as edge habitats, represent a vibrant intersection of life, offering a unique glimpse into ecological processes and the incredible adaptability of species.

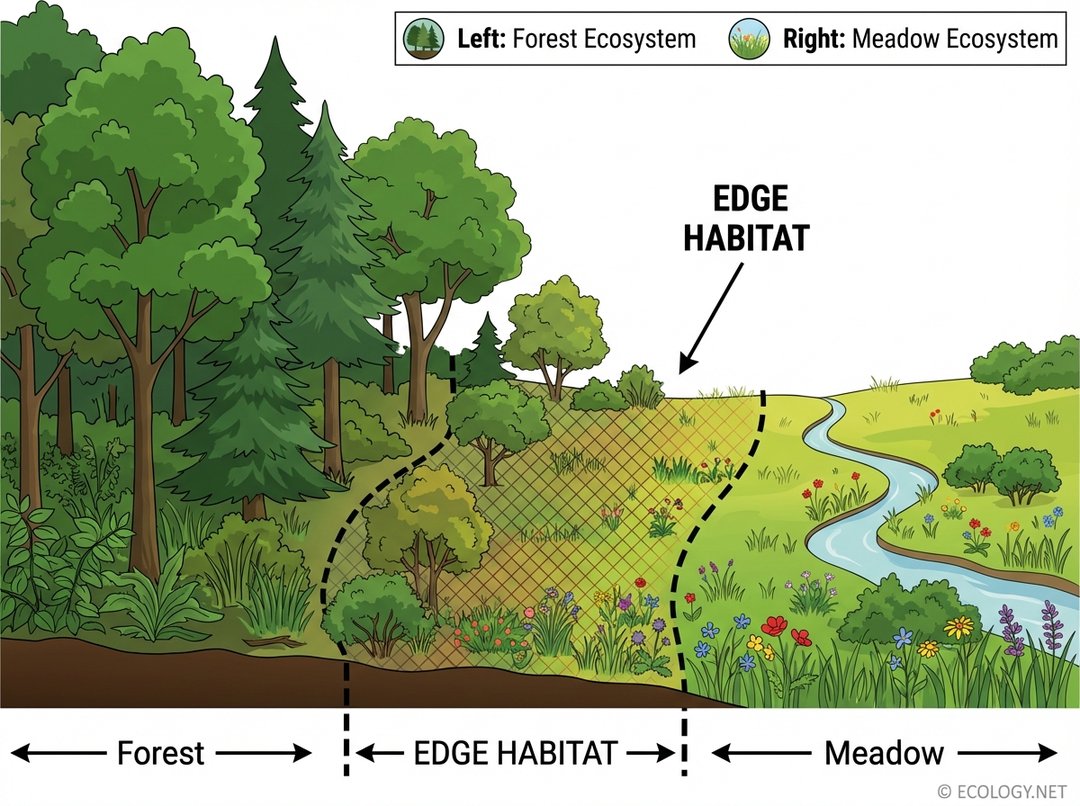

Imagine standing at the very border where a dense, towering forest gives way to an open, sun-drenched meadow. This transitional strip, neither fully forest nor fully meadow, is an edge habitat. It is a place of constant flux, where the conditions of two different worlds collide and blend, creating an environment distinct from either adjacent habitat.

What are Edge Habitats? Defining the Transition Zone

An edge habitat, also known as an ecotone, is fundamentally a transition zone between two distinct ecological communities. It is not merely a line on a map, but a three-dimensional space where environmental conditions and species composition gradually shift from one ecosystem to another. These zones can vary greatly in width, from a few meters to several kilometers, depending on the abruptness of the environmental change.

Consider the classic example of a forest meeting a field. The forest interior is characterized by shade, stable temperatures, high humidity, and specific plant and animal communities adapted to these conditions. The field, conversely, is exposed to full sunlight, experiences greater temperature fluctuations, and supports different species of grasses, wildflowers, and the animals that feed on them. The edge between them offers a blend of these conditions, providing access to resources from both sides.

Edge habitats are not limited to forest-field interfaces. They can be found wherever two different ecosystems meet. Examples include:

- Forests bordering rivers or lakes

- Mountainsides transitioning to valleys

- Deserts meeting scrublands

- Urban areas adjacent to natural parks

- Coastal zones where land meets sea

These transitional areas are crucial for understanding biodiversity and ecological dynamics, often acting as ecological hotspots.

The Ecology of Edges: Why are They So Rich in Life?

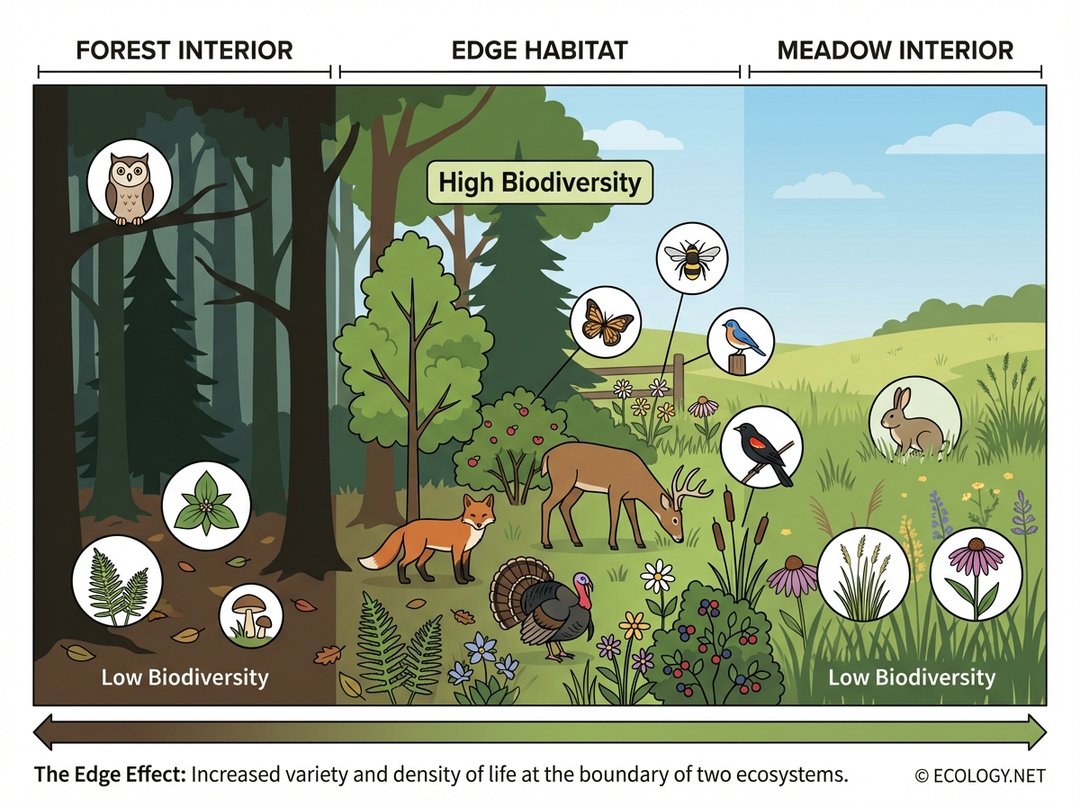

The most compelling characteristic of edge habitats is often their elevated biodiversity, a phenomenon ecologists refer to as the “edge effect.” This effect describes the tendency for the number of species, and sometimes the population densities of certain species, to be greater in edge habitats than in the interior of the adjacent communities.

Why do these borderlands teem with such a variety of life? The answer lies in the unique combination of resources and conditions they offer. Edge habitats provide access to resources from both adjacent ecosystems. For instance, an animal living at a forest edge can forage in the open field for certain foods while retreating into the forest for shelter from predators or harsh weather. This dual access significantly expands the available niche space for many species.

Furthermore, edge habitats often develop their own unique microclimates and vegetation structures. The increased light penetration at a forest edge, for example, can lead to a dense growth of shrubs, vines, and pioneering plant species that would not thrive in the deep shade of the forest interior or the open expanse of the field. This unique vegetation provides additional food sources, nesting sites, and cover, attracting a distinct set of species adapted to these specific conditions.

The Edge Effect: A Deeper Dive into Biodiversity

The heightened biodiversity in edge habitats is a result of several interacting ecological principles:

- Resource Overlap: Species from both adjacent communities can utilize resources found in the edge zone. A deer might browse on forest undergrowth and also graze on meadow grasses.

- Unique Niche Opportunities: The specific environmental conditions of the edge, such as intermediate light levels, temperature gradients, and wind patterns, create niches for species that are specialized for these transitional environments.

- Increased Structural Complexity: Edges often exhibit a greater variety of plant growth forms, from tall trees to shrubs, grasses, and ground cover. This structural diversity provides more varied opportunities for shelter, nesting, and foraging.

- Corridors for Movement: Edges can act as natural pathways or corridors, facilitating the movement of species between different habitat patches, thereby increasing the likelihood of encountering a wider array of organisms.

This combination of factors makes edge habitats incredibly productive and dynamic ecosystems, supporting a rich mosaic of life.

Species That Thrive on the Edge: Examples in Action

Many species have evolved to specifically exploit the advantages offered by edge habitats. These “edge specialists” often exhibit behaviors or adaptations that allow them to thrive in these transitional zones.

- White-tailed Deer: A prime example, white-tailed deer are frequently found along forest edges. They benefit from the dense cover and browse available in the forest for shelter and protection, while also accessing the abundant forage, such as grasses and forbs, found in adjacent open fields.

- Rabbits and Hares: These small mammals often prefer areas with dense shrubbery for cover, which is common at edges, alongside open areas for grazing.

- Brown-headed Cowbirds: This species is notorious for its brood parasitism, laying its eggs in the nests of other birds. Cowbirds are often associated with forest edges, as they can forage in open areas and easily access the nests of host birds in the adjacent forest.

- Many Bird Species: A wide array of songbirds, raptors, and game birds utilize edges. Robins might nest in shrubs at the forest edge and forage for worms in the open lawn. Jays and mockingbirds also frequently inhabit these areas, taking advantage of diverse food sources.

- Pollinators: Butterflies, bees, and other insects are often abundant in edge habitats, particularly where flowering plants from both ecosystems converge, providing a continuous supply of nectar and pollen.

- Predators: Coyotes, foxes, and various raptors often patrol edge habitats, as the increased density of prey species makes these zones attractive hunting grounds.

These examples highlight how edge habitats provide critical resources for a diverse range of wildlife, from herbivores to predators and pollinators.

Types of Edge Habitats: A Spectrum of Transitions

Not all edge habitats are created equal. Ecologists often distinguish between different types of edges based on their origin and characteristics:

Natural Edges

These edges arise from natural processes and disturbances, often forming gradual transitions. Examples include:

- Riverbanks and Lake Shores: The gradual change from aquatic to terrestrial environments.

- Cliffs and Rock Outcrops: Abrupt changes in elevation and substrate.

- Natural Disturbances: Areas affected by wildfires, floods, or landslides can create temporary or long-lasting edges as new vegetation colonizes.

- Ecotones between different soil types or geological formations.

Natural edges tend to be more stable over time and often support highly adapted, unique communities.

Induced or Anthropogenic Edges

These edges are created or significantly altered by human activities. They are often sharper and more abrupt than natural edges, and their ecological impacts can be more complex. Examples include:

- Agricultural Fields bordering Forests: One of the most common induced edges, often very sharp.

- Roads and Highways: These linear features create edges along their entire length, fragmenting habitats.

- Urban Development: The interface between cities or suburbs and natural areas.

- Logging Clear-cuts: Newly logged areas adjacent to intact forests.

Induced edges can sometimes exacerbate negative edge effects, leading to habitat degradation and loss of sensitive species.

The Dual Nature of Edges: Benefits and Challenges

While edge habitats are celebrated for their biodiversity, it is important to recognize their dual nature. They offer significant ecological benefits but also present certain challenges, particularly when they are human-created.

Benefits of Edge Habitats:

- Increased Biodiversity: As discussed, edges often support a greater variety of species than interior habitats.

- Habitat for Generalist Species: Many adaptable species thrive in the varied conditions of edges.

- Resource Access: Provides access to food, water, and shelter from multiple habitat types.

- Genetic Exchange: Can facilitate gene flow between isolated populations by acting as corridors.

Challenges and Negative Edge Effects:

- Increased Predation: Predators, such as raccoons, opossums, and domestic cats, often use edges as hunting grounds, leading to higher predation rates on nests and young animals in edge zones.

- Brood Parasitism: Species like the Brown-headed Cowbird thrive at edges, where they can easily access the nests of forest-dwelling birds to lay their eggs, often at the expense of the host species’ offspring.

- Invasive Species Colonization: The disturbed conditions and increased light at edges make them susceptible to colonization by invasive plant and animal species, which can outcompete native organisms.

- Altered Microclimates: Edges can experience greater wind penetration, increased light, higher temperatures, and lower humidity compared to forest interiors. These changes can negatively impact species that require stable interior conditions.

- Habitat Fragmentation: When human activities create numerous sharp edges, they can effectively fragment larger habitats into smaller, isolated patches. This reduces the amount of interior habitat, making it difficult for species that require large, undisturbed areas to survive.

Understanding these trade-offs is crucial for effective conservation and land management.

Managing Edge Habitats: Conservation and Land Use

Given the complex ecological role of edge habitats, their management is a critical aspect of conservation. The goal is often to maximize the benefits of edges while mitigating their potential negative impacts.

- Creating Soft Edges: Instead of abrupt, sharp transitions (like a clear-cut meeting a forest), creating gradual, “soft” edges with a gradient of vegetation (e.g., tall trees transitioning to shrubs, then to grasses) can reduce negative edge effects and enhance biodiversity.

- Minimizing Fragmentation: In areas where human development is unavoidable, efforts should be made to minimize the creation of new edges and to maintain large, contiguous blocks of interior habitat.

- Restoring Degraded Edges: Removing invasive species, planting native vegetation, and creating buffer zones can help restore the ecological integrity of degraded edge habitats.

- Considering Edge Orientation: The direction an edge faces (e.g., north-facing versus south-facing) can influence its microclimate and species composition, a factor that can be considered in landscape planning.

- Wildlife Corridors: Utilizing edges as part of broader wildlife corridor networks can help connect fragmented habitats and facilitate species movement.

Thoughtful management of edge habitats is essential for maintaining healthy ecosystems, especially in landscapes increasingly shaped by human activity.

Conclusion

Edge habitats are far more than simple boundaries; they are dynamic, complex, and ecologically vital zones where life flourishes in unique ways. From the increased biodiversity driven by the “edge effect” to the specific adaptations of species that call these transitions home, edges offer a compelling study in ecological resilience and interaction.

While they present both opportunities and challenges, particularly in human-dominated landscapes, a deeper understanding and careful management of edge habitats can unlock their full potential as hotspots of life. By appreciating these fascinating borderlands, we gain a richer perspective on the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the intricate dance of life that unfolds at their seams.