In the grand tapestry of agriculture, few practices are as fundamental and ecologically sound as crop rotation. It is a time-honored strategy, refined over centuries, that stands as a testament to humanity’s understanding of natural cycles and their profound impact on the land. Far from being a mere farming technique, crop rotation is a sophisticated dance with nature, a proactive approach to cultivating healthy soil, robust crops, and a sustainable future.

What is Crop Rotation?

At its heart, crop rotation is the practice of growing a series of different types of crops in the same area across a sequence of growing seasons. Instead of planting the same crop year after year, farmers strategically vary what they cultivate. This seemingly simple change unleashes a cascade of benefits, transforming the health and productivity of agricultural land.

Why Monoculture is a Problem

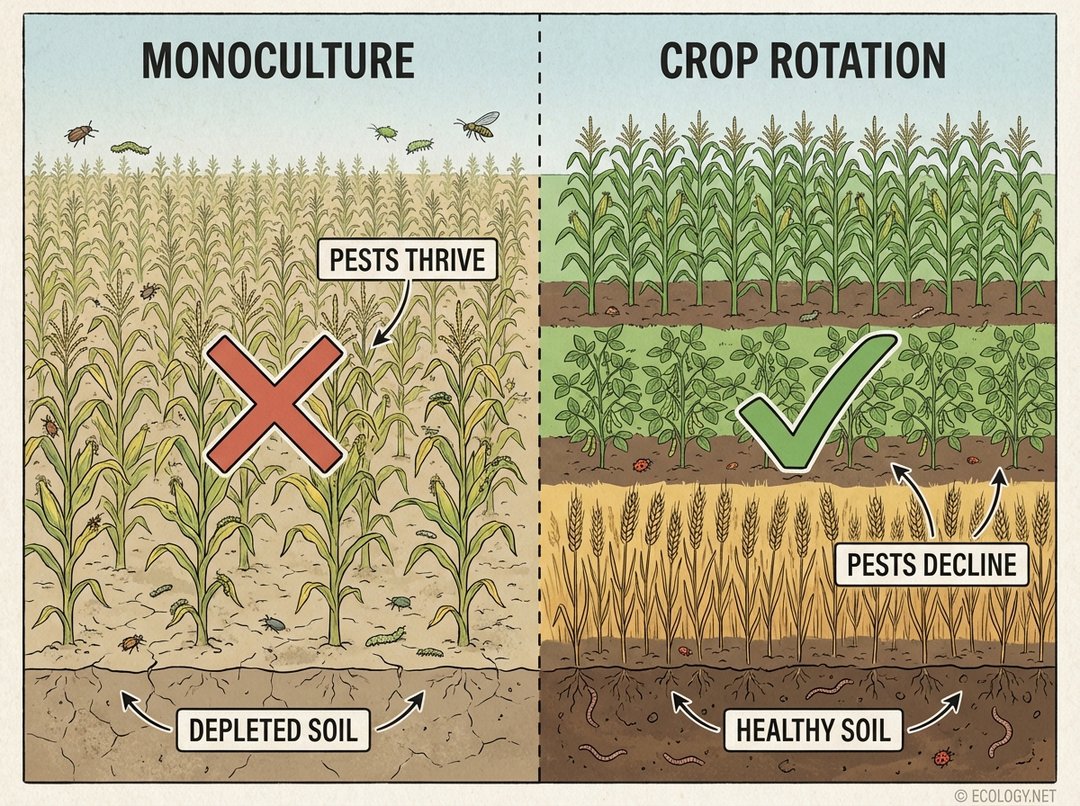

To truly appreciate the genius of crop rotation, one must first understand the pitfalls of its opposite: monoculture. Monoculture is the practice of growing a single crop species repeatedly on the same land. While it might offer short-term efficiencies in planting and harvesting, its long-term consequences are often detrimental to both the environment and agricultural sustainability.

- Nutrient Depletion: Every plant has specific nutrient requirements. When the same crop is grown repeatedly, it continuously draws the same nutrients from the soil, leading to a rapid depletion of essential elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. This forces farmers to rely heavily on synthetic fertilizers, which can have their own environmental drawbacks.

- Pest and Disease Buildup: A field of a single crop is an open invitation for pests and diseases that specifically target that crop. Without any interruption in their food source or host, these populations can explode, leading to widespread damage and an increased need for pesticides. This creates a vicious cycle, where more chemicals are needed to combat problems exacerbated by the farming method itself.

- Soil Degradation: Monoculture often leads to a decline in soil organic matter and microbial diversity. The soil structure can deteriorate, making it more susceptible to erosion by wind and water. This loss of healthy soil is a direct threat to long-term agricultural viability.

- Reduced Biodiversity: Large expanses of a single crop create biological deserts, offering little habitat or food for beneficial insects, pollinators, and other wildlife that contribute to a healthy ecosystem.

The Core Principles of Crop Rotation

Crop rotation directly addresses the problems of monoculture by leveraging fundamental ecological principles. It is a proactive strategy that works with nature, rather than against it.

Nutrient Cycling and Soil Health

One of the most profound benefits of crop rotation is its ability to enhance soil fertility naturally. Different crops interact with the soil in distinct ways:

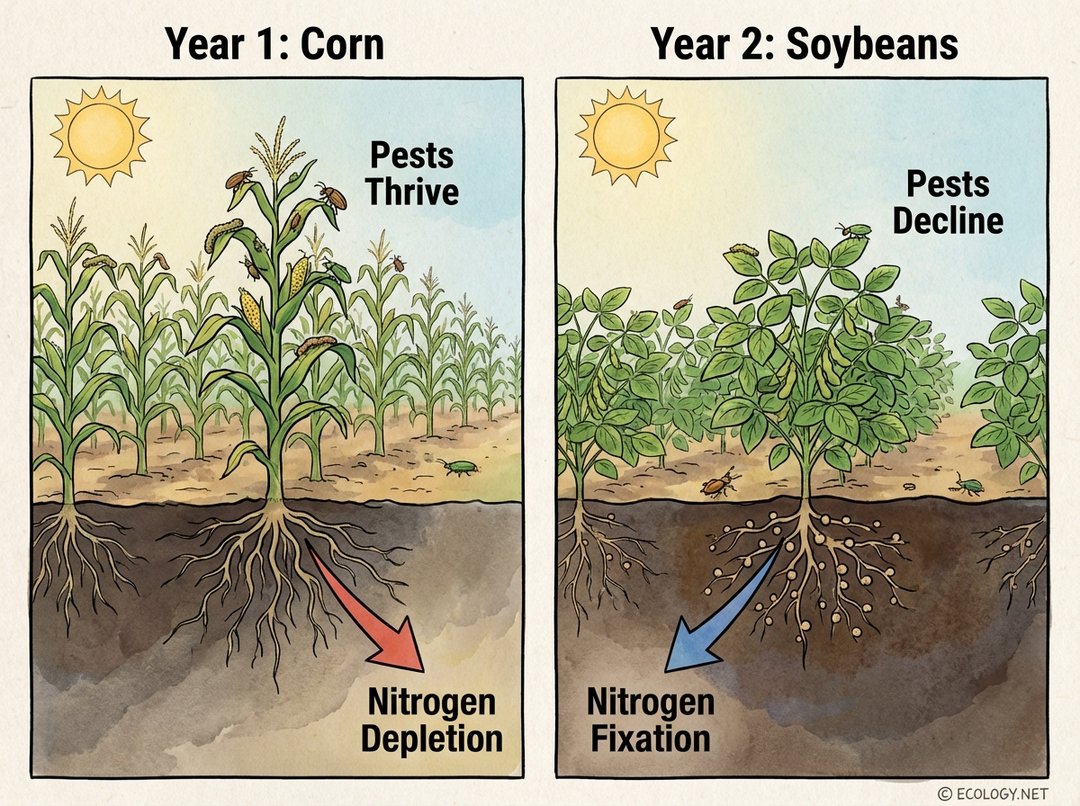

- Nitrogen Fixers: Leguminous plants, such as soybeans, peas, clover, and alfalfa, have a remarkable ability to form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their root nodules. These bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form usable by plants, enriching the soil with this vital nutrient. Planting legumes after a nitrogen-demanding crop like corn replenishes the soil’s nitrogen stores, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Nutrient Scavengers: Some crops, particularly those with deep root systems like alfalfa or certain grains, can access nutrients from deeper soil layers that shallower-rooted crops cannot reach. When these plants decompose, they bring those nutrients closer to the surface, making them available for subsequent crops.

- Organic Matter Contribution: Diverse root systems and varying plant residues contribute a greater variety of organic matter to the soil. This organic matter improves soil structure, water retention, and provides food for a thriving community of beneficial microorganisms, which are the unsung heroes of soil health.

Pest and Disease Interruption

Crop rotation is a powerful tool in integrated pest management. By breaking the continuous cycle of a host plant, it disrupts the life cycles of pests and pathogens.

- Starvation and Disorientation: Pests that specialize in a particular crop will find their food source gone in the subsequent season. This can starve them out or force them to migrate, significantly reducing their populations. Similarly, disease-causing pathogens in the soil lose their host and decline over time.

- Beneficial Organism Support: A diverse rotation can support a wider array of beneficial insects and microorganisms that prey on or outcompete pests and diseases.

Weed Management

Varying crops also helps in managing weeds. Different crops have different growth habits, planting times, and cultivation requirements. This variation can disrupt weed life cycles and prevent specific weed species from dominating a field.

Benefits of Crop Rotation

The advantages of implementing crop rotation extend far beyond the immediate field, touching upon environmental health, economic stability, and food security.

- Enhanced Soil Fertility: Naturally enriches the soil with essential nutrients, reducing reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

- Reduced Pest and Disease Pressure: Minimizes the need for chemical pesticides and herbicides, leading to healthier ecosystems.

- Improved Soil Structure: Increases organic matter, enhances water infiltration, and reduces soil erosion.

- Increased Crop Yields: Healthier soil and fewer pests often translate to more robust and productive harvests.

- Economic Savings: Lower input costs for fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides can significantly improve a farm’s profitability.

- Environmental Stewardship: Contributes to biodiversity, protects water quality, and sequesters carbon in the soil.

Designing a Crop Rotation Plan

Crafting an effective crop rotation plan requires thoughtful consideration of several factors. It is not a one-size-fits-all solution, but rather a tailored strategy based on local climate, soil type, available crops, and market demands.

Key Considerations:

- Crop Families: Grouping crops by family (e.g., Solanaceae, Brassicaceae, Leguminosae) is crucial because members of the same family often share similar nutrient requirements, pests, and diseases. Rotating between different families helps break these cycles.

- Root Depths: Alternate between shallow-rooted crops (like lettuce or spinach) and deep-rooted crops (like alfalfa or carrots) to utilize nutrients from different soil horizons and improve soil structure throughout the profile.

- Nutrient Demands: Follow heavy feeders (e.g., corn, potatoes) with light feeders (e.g., herbs) or nitrogen-fixing legumes to balance soil nutrient levels.

- Pest and Disease Susceptibility: Avoid planting crops susceptible to the same pests or diseases consecutively. For example, if a field had a potato blight issue, avoid planting other Solanaceae crops like tomatoes or peppers in the following year.

- Residue Management: Consider the amount and type of residue each crop leaves behind. Some residues can suppress weeds or add significant organic matter.

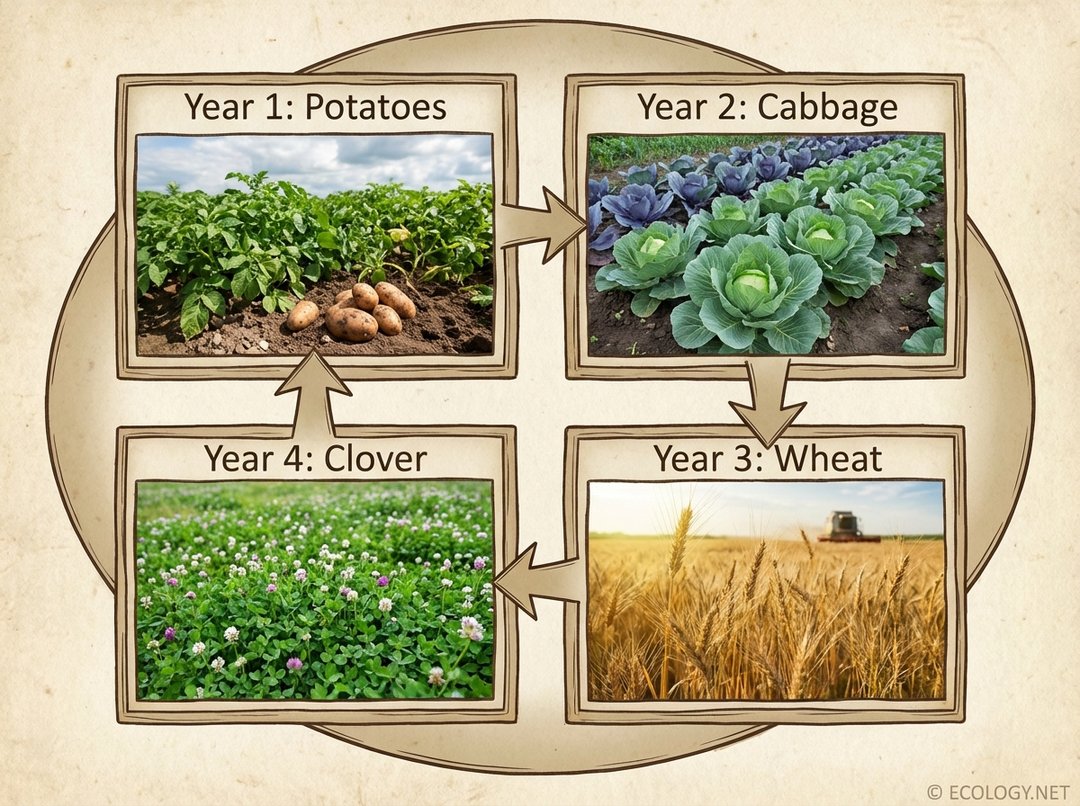

Classic Crop Rotation Examples

Historical and modern agricultural systems offer numerous examples of successful crop rotation. These models provide a framework that can be adapted to various contexts.

The Norfolk Four-Course System

One of the most famous and influential crop rotation systems, developed in Norfolk, England, in the 18th century, revolutionized agriculture. It typically involved:

- Year 1: Wheat (a cash crop, heavy feeder)

- Year 2: Turnips (a root crop, fed to livestock, helps clean the field of weeds)

- Year 3: Barley (another grain, often undersown with clover)

- Year 4: Clover (a legume, nitrogen fixer, forage for livestock, improves soil structure)

This system was brilliant because it integrated livestock, replenished soil nitrogen, provided diverse food sources, and controlled weeds, all without leaving land fallow.

Simple Two-Year Rotations

- Corn – Soybeans: A very common rotation in many parts of the world. Corn is a heavy nitrogen feeder, and soybeans, being a legume, replenish nitrogen. This also helps break the life cycles of pests specific to either crop.

- Wheat – Fallow/Cover Crop: In drier regions, a year of wheat followed by a year of fallow or a cover crop can help conserve moisture and build soil health.

More Complex Multi-Year Rotations

Many modern organic and sustainable farms employ rotations that span three, four, or even more years, incorporating a wider variety of crops including vegetables, grains, legumes, and cover crops. These longer rotations offer maximum benefits in terms of pest control, nutrient cycling, and soil building.

A well-designed rotation is like a symphony for the soil, where each crop plays a vital role in maintaining harmony and productivity.

Challenges and Considerations

While the benefits of crop rotation are undeniable, implementing it effectively can present certain challenges:

- Market Demands: Farmers often face pressure to grow high-value cash crops, which can make it difficult to incorporate less profitable rotation crops.

- Farm Size and Equipment: Smaller farms or those with specialized equipment might find it challenging to diversify their crop portfolio.

- Knowledge and Planning: Designing an optimal rotation requires a deep understanding of crop biology, soil science, and local ecological conditions. It demands careful planning and record-keeping.

- Transition Period: Shifting from monoculture to a rotational system may involve an initial learning curve and potentially some adjustments in yield or management practices.

The Future of Farming is Rotational

Crop rotation is not just an ancient practice; it is a cornerstone of modern sustainable agriculture. As the world grapples with challenges like climate change, soil degradation, and food security, the principles of crop rotation become ever more relevant. It offers a pathway to reduce reliance on synthetic inputs, enhance biodiversity, build resilient farming systems, and ensure the long-term health of our planet’s most precious resource: its soil.

Embracing crop rotation is an investment in the future, a commitment to working with nature to produce abundant, healthy food for generations to come. It is a powerful reminder that sometimes, the most innovative solutions are those that look back to the wisdom of ecological balance.