The natural world is a tapestry woven with countless species, each playing a vital role in the intricate dance of ecosystems. Yet, this delicate balance is increasingly threatened by human activities, leading to unprecedented rates of biodiversity loss. In the face of such challenges, a powerful scientific discipline has emerged, offering a beacon of hope and a suite of tools to safeguard life on Earth: conservation genetics.

Conservation genetics is the application of genetic principles and methods to the conservation of biodiversity. It delves into the very blueprint of life, DNA, to understand, monitor, and protect species and populations. By examining the genetic makeup of organisms, scientists can uncover crucial information about their health, adaptability, and long-term survival prospects, guiding effective conservation strategies.

The Blueprint of Life: Understanding Genetic Diversity

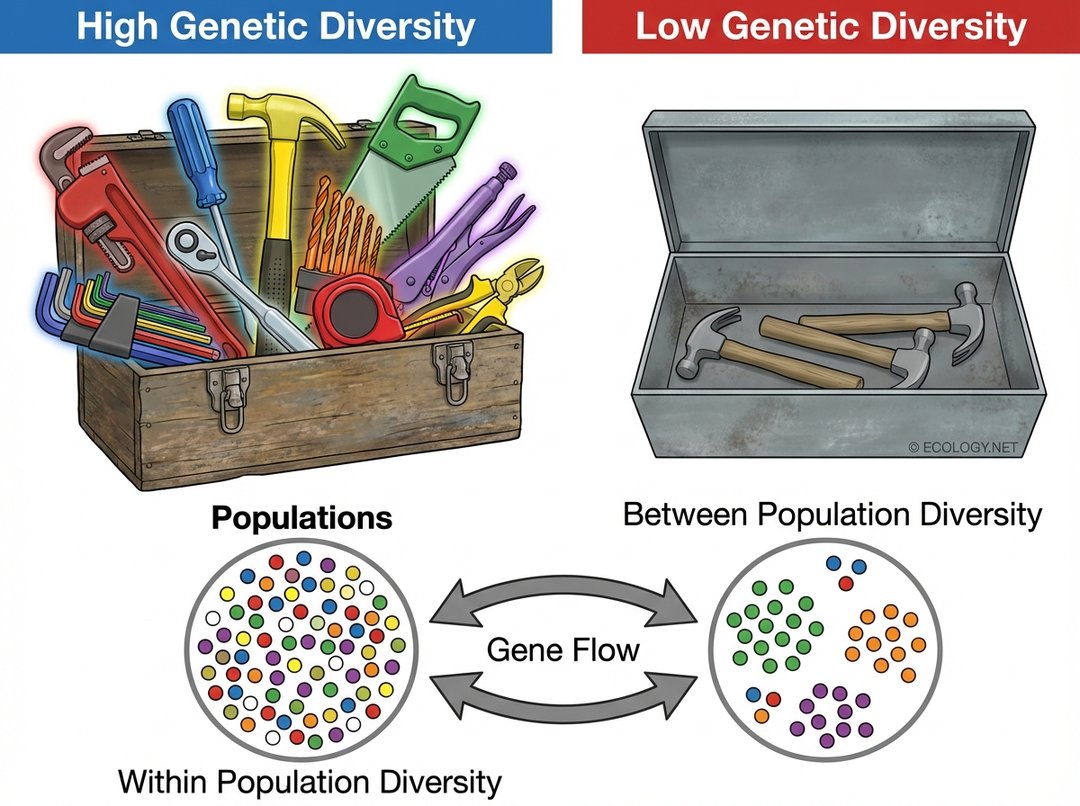

At the heart of conservation genetics lies the concept of genetic diversity. Imagine a toolbox filled with a wide array of tools: wrenches, screwdrivers, hammers, saws, pliers. Each tool serves a specific purpose, allowing you to tackle various repair jobs. Now, imagine a toolbox with only a few identical hammers. Which toolbox would you rather have when faced with an unexpected problem?

Genetic diversity is much like that well-stocked toolbox for a species. It refers to the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species. This diversity manifests in two key ways:

- Within Population Diversity: This is the variation among individuals within a single population. A population with high within-population diversity has many different versions of genes (alleles) spread among its members. This is crucial because it provides the raw material for adaptation.

- Between Population Diversity: This refers to the genetic differences between distinct populations of the same species. Different populations might have evolved unique adaptations to their local environments, leading to distinct genetic profiles.

Why is this diversity so important? It is the foundation of a species’ resilience and its ability to adapt to changing environments. Just as a diverse toolbox allows a repair person to fix many different problems, a genetically diverse population has a greater chance of containing individuals with traits that can help them survive new diseases, climate shifts, or habitat changes. Without this variation, a species becomes vulnerable, like a house built on a shaky foundation.

Threats to Genetic Health: When Diversity Declines

Unfortunately, many human activities inadvertently erode genetic diversity, pushing species closer to the brink. Understanding these threats is the first step toward mitigation.

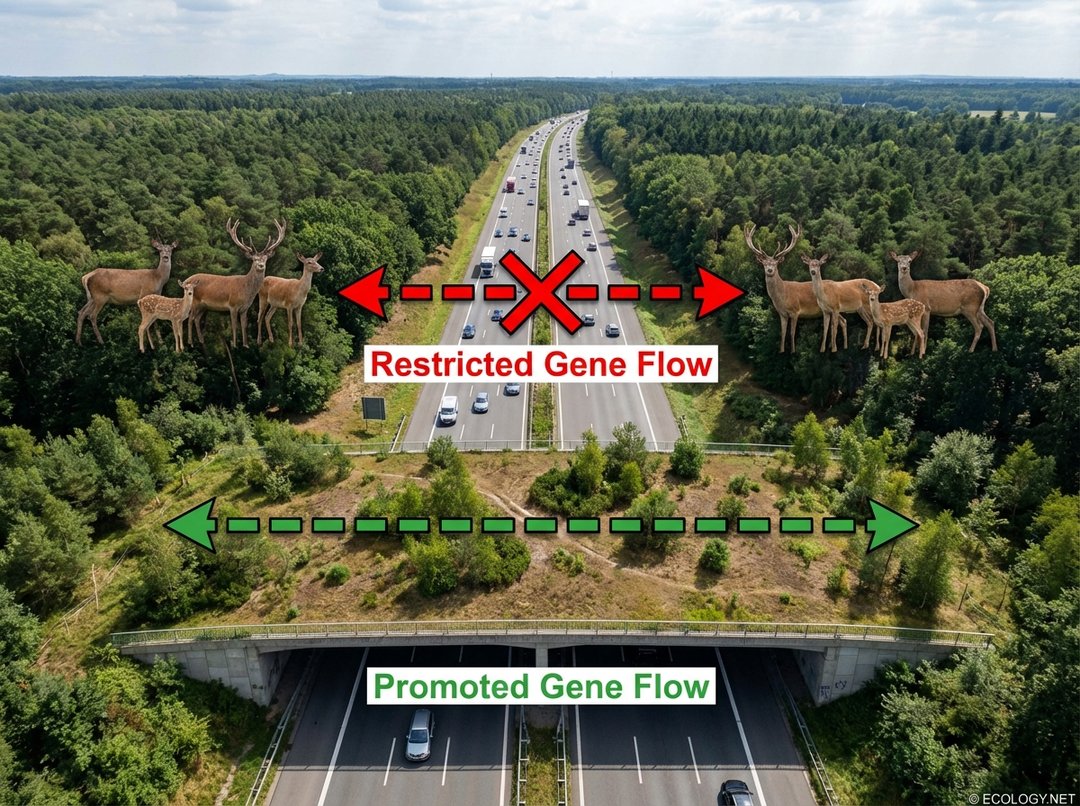

- Habitat Fragmentation: When natural habitats are broken into smaller, isolated patches by roads, agriculture, or urban development, populations become separated. This isolation prevents individuals from different groups from interbreeding, leading to a loss of gene flow.

- Inbreeding: In small, isolated populations, individuals are more likely to mate with close relatives. This inbreeding increases the chances of offspring inheriting two copies of harmful recessive genes, leading to reduced fitness, lower reproductive success, and increased susceptibility to disease. This phenomenon is known as inbreeding depression.

- Genetic Drift: In very small populations, random chance can cause certain alleles to become more or less common, or even disappear entirely, simply by accident. This “sampling error” is much more pronounced in small groups and can lead to a rapid loss of genetic diversity, irrespective of natural selection.

- Population Bottlenecks: A severe reduction in population size due to a catastrophic event (like a natural disaster or overhunting) can drastically reduce genetic diversity. Even if the population recovers in numbers, the genetic diversity may remain low for many generations, making the species less adaptable.

Consider the cheetah, a species that experienced a severe population bottleneck thousands of years ago. Today, cheetahs exhibit remarkably low genetic diversity, making them highly susceptible to diseases and environmental changes. This lack of genetic variation is a major concern for their long-term survival.

Bridging the Gaps: The Role of Gene Flow

Gene flow, the movement of genes between populations, is a critical process for maintaining genetic diversity and preventing the negative effects of isolation. When populations are connected, individuals can migrate and breed with members of other groups, introducing new genetic material and counteracting inbreeding and genetic drift.

However, habitat fragmentation often acts as a formidable barrier to gene flow. A busy highway, for instance, can effectively isolate two forest patches, preventing animals from crossing and exchanging genetic material. This leads to isolated populations that become genetically distinct and often less healthy over time.

Conservation geneticists play a crucial role in identifying these barriers and proposing solutions. By analyzing genetic patterns, they can determine if populations are isolated and how much gene flow is occurring. This information then informs the design of wildlife corridors, underpasses, or overpasses, which are essentially bridges or tunnels that allow animals to safely move between fragmented habitats, restoring vital gene flow.

Tools of the Trade: How Geneticists Unravel Nature’s Secrets

To understand and address these genetic challenges, conservation geneticists employ a sophisticated array of techniques. These tools allow them to read the genetic code, identify individuals, track populations, and even detect species without ever seeing them.

Traditional Genetic Markers

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): This type of DNA is inherited solely from the mother and evolves relatively quickly. It is often used to trace maternal lineages, understand population structure, and identify distinct evolutionary units within a species.

- Microsatellites: These are short, repetitive DNA sequences that vary greatly among individuals. They act like genetic fingerprints, allowing scientists to identify individuals, determine parentage, estimate population size, and measure genetic diversity.

Advanced Genomic Approaches

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has revolutionized conservation genetics, moving from analyzing a few genetic markers to examining entire genomes.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): This technology allows for the rapid and cost-effective sequencing of vast amounts of DNA. It provides a comprehensive view of genetic variation across an entire genome, enabling researchers to identify genes associated with adaptation, disease resistance, or susceptibility to environmental stressors.

- Genomic-Wide Association Studies (GWAS): By analyzing millions of genetic markers across the genome, GWAS can link specific genes or regions of the genome to particular traits, such as disease resistance or tolerance to pollution. This information is invaluable for identifying individuals or populations with desirable adaptive traits for conservation breeding programs.

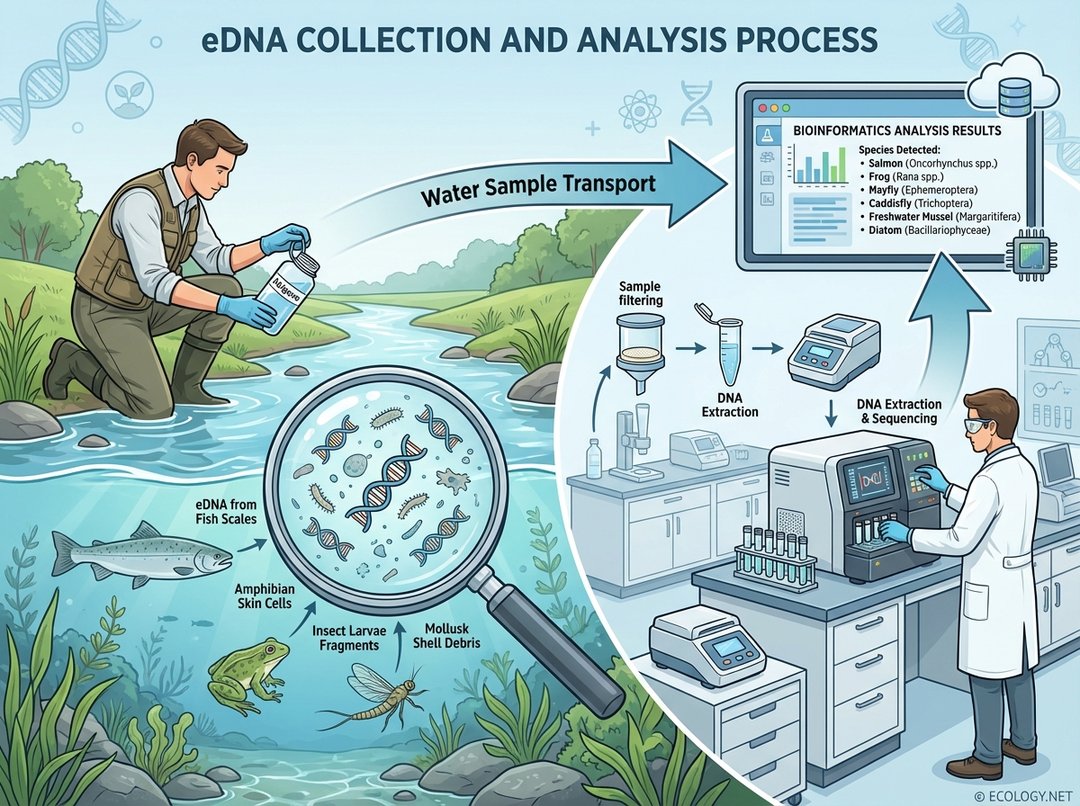

Environmental DNA (eDNA): The Unseen Detectives

One of the most exciting and rapidly developing tools is environmental DNA (eDNA). Organisms constantly shed genetic material into their environment through skin cells, feces, urine, or mucus. This eDNA can be collected from water, soil, or even air samples and then analyzed to detect the presence of species without direct observation.

eDNA offers numerous advantages:

- Non-invasive: It avoids disturbing sensitive species or habitats.

- High Sensitivity: It can detect rare or elusive species that are difficult to find through traditional surveys.

- Cost-Effective: In some cases, it can be more efficient than extensive field surveys.

For example, eDNA has been successfully used to detect invasive species in aquatic environments, monitor endangered amphibians in remote ponds, and even identify the presence of large mammals in forest samples. It is a game-changer for biodiversity monitoring, especially for species that are difficult to observe directly.

Conservation in Action: Practical Applications

The insights gleaned from conservation genetics are not merely academic; they translate directly into tangible conservation actions. Here are some key applications:

- Identifying Management Units: Genetic data helps define distinct populations or “management units” within a species. These units might require separate conservation strategies because they are genetically unique or isolated. For example, genetic analysis might reveal that a species thought to be widespread actually consists of several genetically distinct populations, each needing tailored protection.

- Designing Reintroduction Programs: When reintroducing species into areas where they have been extirpated, geneticists can select individuals from source populations that have high genetic diversity and are genetically compatible, maximizing the chances of a successful re-establishment. They can also ensure that the reintroduced population has the genetic variation needed to adapt to its new environment.

- Combating Illegal Wildlife Trade: Genetic forensics uses DNA analysis to identify the species and even the geographic origin of confiscated wildlife products (e.g., ivory, rhino horn, timber). This information helps law enforcement track down poachers and illegal traders, providing crucial evidence for prosecution.

- Managing Captive Breeding Programs: Zoos and conservation centers use genetic data to manage breeding programs for endangered species. By carefully selecting breeding pairs, they can minimize inbreeding and maintain genetic diversity, ensuring that captive populations remain healthy and viable for potential reintroduction into the wild.

- Monitoring Population Health: Regular genetic monitoring can track changes in genetic diversity over time, providing early warnings of population decline or genetic erosion. This allows conservationists to intervene before a crisis becomes irreversible.

A striking example of conservation genetics in action is the recovery of the California Condor. Genetic analysis helped guide breeding programs and reintroduction efforts, ensuring genetic health in a species brought back from the brink of extinction.

Challenges and the Future of Conservation Genetics

While immensely powerful, conservation genetics faces its own set of challenges. The cost of genomic sequencing can be high, especially for large-scale projects. Interpreting complex genetic data requires specialized expertise, and integrating genetic findings with ecological and demographic data is essential for holistic conservation planning.

The future of conservation genetics is bright and rapidly evolving. Advances in bioinformatics, artificial intelligence, and portable sequencing devices promise to make genetic tools even more accessible and powerful. The integration of genetic data with satellite imagery, climate modeling, and citizen science initiatives will create a more comprehensive understanding of biodiversity and the threats it faces.

Ultimately, conservation genetics is more than just a scientific discipline; it is a critical ally in the global effort to protect Earth’s biodiversity. By peering into the genetic code, we gain profound insights into the past, present, and future of life, empowering us to make informed decisions and build a more resilient future for all species, including our own.