Life on Earth is a grand tapestry woven from countless interactions, a complex dance where organisms constantly influence one another. From the fierce competition for resources to the intimate partnerships that define symbiosis, understanding these relationships is fundamental to grasping the intricate web of ecology. Among these fascinating connections lies commensalism, a subtle yet widespread form of interaction that often goes unnoticed but plays a vital role in many ecosystems.

Unpacking the Spectrum of Biological Interactions

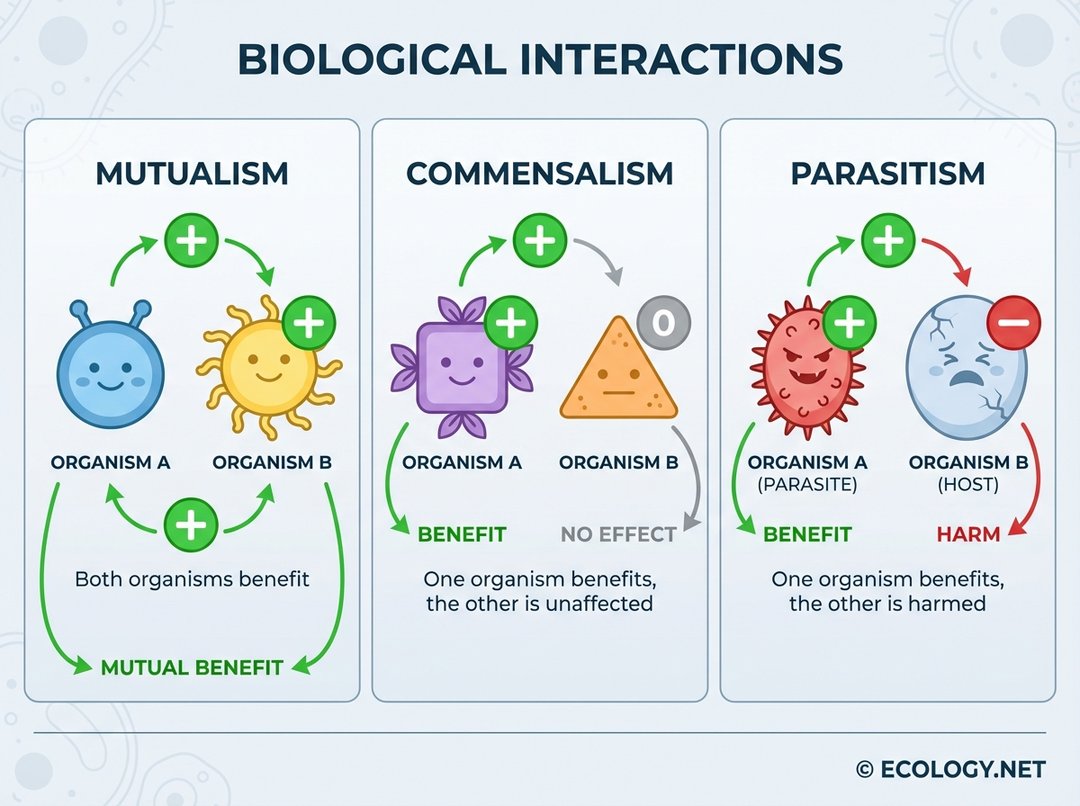

To truly appreciate commensalism, it is helpful to first place it within the broader context of biological interactions. Ecologists categorize these relationships based on the impact each organism has on the other. The three primary symbiotic relationships are mutualism, parasitism, and commensalism.

- Mutualism: This is a “win-win” scenario where both interacting species benefit from the relationship. A classic example is the relationship between bees and flowering plants, where bees get nectar and pollen, and plants achieve pollination.

- Parasitism: In this “win-lose” interaction, one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host, which is harmed. Ticks feeding on the blood of mammals exemplify this relationship.

- Commensalism: This is the focus of our exploration, a “win-neutral” interaction where one species benefits, and the other is neither significantly helped nor harmed. It is a relationship of quiet coexistence, where one party thrives without imposing a cost on its partner.

Defining Commensalism: A Closer Look at “Unaffected”

The core of commensalism lies in the concept of one organism benefiting while the other remains “unaffected.” This “unaffected” status is crucial and can sometimes be challenging to definitively prove in nature. It implies that the host organism experiences no measurable positive or negative impact on its fitness, survival, or reproductive success due to the presence of the commensal. The commensal, however, gains advantages such as food, shelter, support, or transportation.

Consider a bird nesting in a tree. The bird gains a safe place to raise its young, while the tree, typically large and robust, is generally not significantly impacted by the nest’s presence. The tree’s growth, health, or ability to reproduce remains largely unchanged. This subtle balance is what defines commensalism.

Classic Examples from the Natural World

The natural world is replete with examples of commensalism, showcasing the ingenuity of life in finding ways to thrive without causing harm. These examples highlight the diverse strategies organisms employ to gain an advantage.

The Remora and the Shark: A Hitchhiker’s Tale

One of the most iconic illustrations of commensalism involves the remora fish and larger marine animals, particularly sharks.

Remoras possess a highly specialized dorsal fin modified into a powerful suction cup, allowing them to firmly attach themselves to the bodies of sharks, whales, manta rays, and even sea turtles. What do they gain from this unique partnership?

- Transportation: Remoras expend minimal energy as they are carried effortlessly across vast ocean distances, accessing new feeding grounds.

- Protection: By associating with a large, formidable predator like a shark, remoras gain a degree of protection from their own potential predators.

- Food Scraps: As the shark feeds, remoras detach to snatch leftover morsels, scraps, and parasites from the shark’s skin, effectively cleaning it.

From the shark’s perspective, the remora’s presence is generally considered neutral. The small drag created by the remora is negligible for such a powerful swimmer, and the removal of parasites might even be a slight benefit, though not significant enough to classify the interaction as mutualism.

Other Notable Examples:

- Cattle Egrets and Grazing Livestock: These birds often follow herds of cattle, horses, or other grazing animals. As the livestock move through fields, they disturb insects and other small invertebrates, flushing them out. The egrets then easily catch and consume these dislodged prey, benefiting from the animals’ foraging activities without affecting the livestock.

- Barnacles on Whales: Barnacles are sessile crustaceans that attach themselves to hard surfaces. Many species affix themselves to the skin of whales. They benefit from constant access to nutrient-rich water currents for filter feeding and gain transportation to new areas. The whale, with its massive size, is generally unaffected by the barnacles’ presence.

- Scavengers and Predators: Many scavenger species, such as jackals or vultures, follow large predators like lions or wolves. They benefit by feeding on the remains of kills left behind by the predators, without impacting the predator’s hunting success or food availability.

The Ecological Significance of Commensalism

While seemingly less dramatic than mutualism or parasitism, commensalism plays a crucial role in shaping ecological communities. It allows for the efficient utilization of resources and habitats, enabling a greater diversity of life to coexist within an ecosystem. By finding niches that do not compete directly with dominant species, commensals can expand the overall biodiversity and complexity of a given environment. It demonstrates how organisms can find ways to thrive by leveraging the activities or structures of others without causing detriment.

Diverse Manifestations: Types of Commensalism

Commensalism is not a monolithic concept; it manifests in several distinct forms, each characterized by the specific nature of the benefit gained by the commensal. Understanding these types provides a deeper appreciation for the versatility of this ecological interaction.

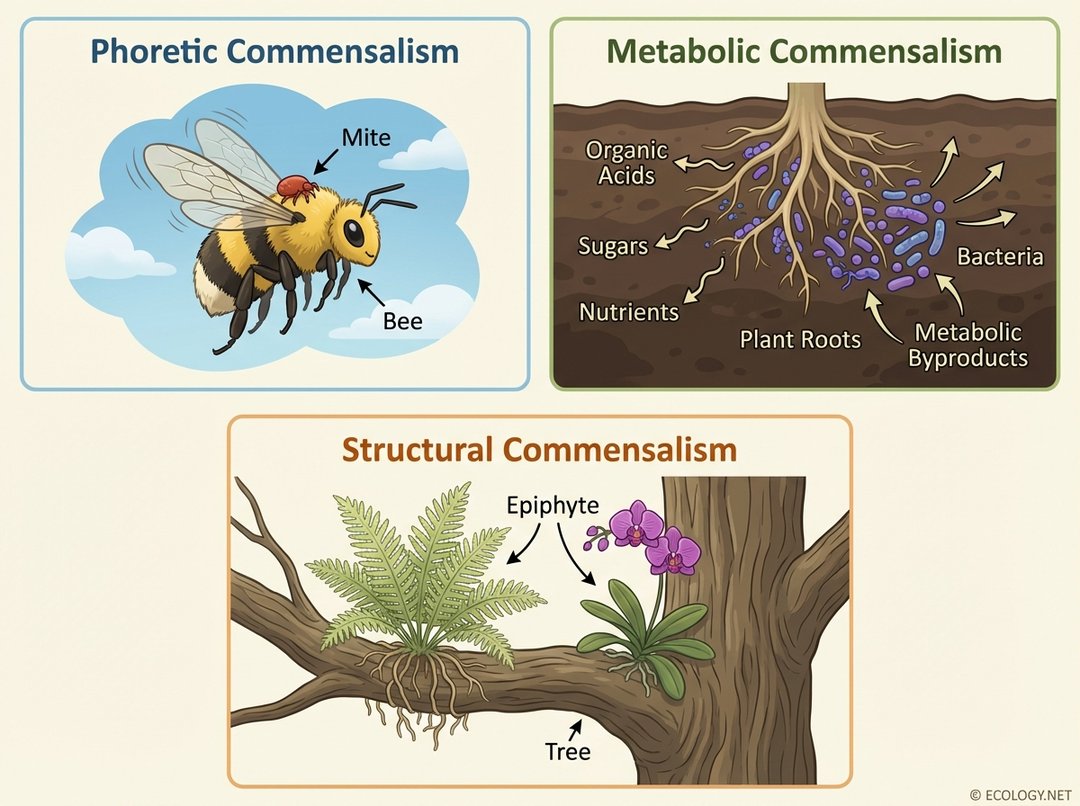

1. Phoretic Commensalism (Phoresy)

Phoresy describes a relationship where one organism uses another for transportation. The term “phoresy” comes from the Greek word “phorein,” meaning “to carry.” The host is simply a vehicle, and the commensal gains mobility.

- Examples:

- Mites on Insects: Many species of mites attach themselves to larger insects like beetles or bees. They hitch a ride to new locations, which can be crucial for finding new food sources or mates, without harming their insect host.

- Barnacles on Whales: As mentioned earlier, this is a prime example of phoresy, where barnacles gain transportation.

2. Inquilinism

Inquilinism involves one organism living within the shelter or home of another organism. The commensal benefits from protection, shelter, or a stable microenvironment provided by the host’s dwelling.

- Examples:

- Pistol Shrimp and Sponges: Some species of pistol shrimp live within the internal cavities of sponges, gaining protection from predators.

- Owl Mites in Owl Nests: These mites live in the nests of owls, feeding on detritus and leftover food scraps without affecting the owls themselves.

- Small Fish in Sea Anemones: While clownfish have a mutualistic relationship with anemones, some other small fish species might simply use the anemone’s stinging tentacles for protection without offering any benefit in return.

3. Metabolic Commensalism

This type of commensalism occurs when one organism modifies the environment or produces metabolic byproducts that another organism can then utilize. The commensal benefits from the metabolic activities of the host.

- Examples:

- Bacteria in Soil: Certain bacteria in the soil might break down complex organic matter, releasing simpler compounds that other bacterial species can then consume. The initial decomposers are unaffected by the secondary consumers.

- Scavengers and Predators: The relationship where scavengers consume the waste or leftovers from a predator’s meal can also be considered a form of metabolic commensalism, as the predator’s metabolic activity (hunting and eating) creates a resource for the scavenger.

4. Structural Commensalism (Epiphytes)

Structural commensalism, often exemplified by epiphytes, involves one organism using another for physical support or a place to grow. The host provides a substrate, often elevating the commensal to better light or air conditions, without being significantly affected itself.

- Examples:

- Orchids and Ferns on Trees: Many species of orchids, ferns, and bromeliads grow on the branches or trunks of larger trees in tropical rainforests. These epiphytes benefit from being elevated into the canopy, gaining better access to sunlight and rainfall, without drawing nutrients from the tree or harming it.

- Algae on Turtle Shells: Algae growing on the shells of slow-moving turtles gain a stable substrate and access to sunlight, while the turtle is generally unaffected.

5. Chemical Commensalism

A less commonly discussed but equally fascinating form, chemical commensalism involves one organism benefiting from chemical signals or compounds produced by another. This can include using alarm pheromones, waste products, or other chemical cues.

- Example: Certain microorganisms might thrive in environments where another species has detoxified a harmful chemical or produced a growth-promoting substance, without the producer being affected.

The Shifting Sands of Ecological Classification

It is important to acknowledge that classifying biological interactions is not always straightforward. What appears to be commensalism can, under different circumstances or with more detailed study, reveal itself as a subtle form of mutualism or even parasitism. For instance, if the remora’s drag on the shark becomes significant enough to impact its hunting efficiency, the relationship could lean towards parasitism. Conversely, if the remora’s cleaning services prove more beneficial than previously thought, it might approach mutualism.

Environmental conditions, population densities, and the specific species involved can all influence the nature of an interaction. This dynamic aspect highlights the complexity and interconnectedness of ecosystems, reminding us that nature rarely fits neatly into rigid categories.

Conclusion: The Quiet Architects of Coexistence

Commensalism, often overshadowed by the more dramatic tales of predator and prey or the intricate partnerships of mutualism, is a testament to the diverse strategies life employs to survive and thrive. From microscopic mites hitching rides on bees to majestic orchids adorning ancient trees, these “win-neutral” relationships demonstrate how organisms can find their niche by leveraging the presence of others without causing harm. Understanding commensalism enriches our appreciation for the subtle balances and intricate interdependencies that define the living world, revealing the quiet architects of coexistence that shape our planet’s incredible biodiversity.