Unraveling Climate Feedbacks: The Hidden Engines of Global Change

Imagine pushing a swing. A small push makes it go a little higher. Another push, timed just right, makes it go even higher. This simple act illustrates a powerful concept at the heart of our planet’s climate system: feedback loops. Climate feedbacks are processes that can either amplify or dampen an initial change in temperature, acting as crucial accelerators or brakes on global warming. Understanding these intricate loops is not just for scientists; it is essential for anyone seeking to grasp the full scope of climate change and its potential trajectory.

The Basics: Positive and Negative Feedbacks

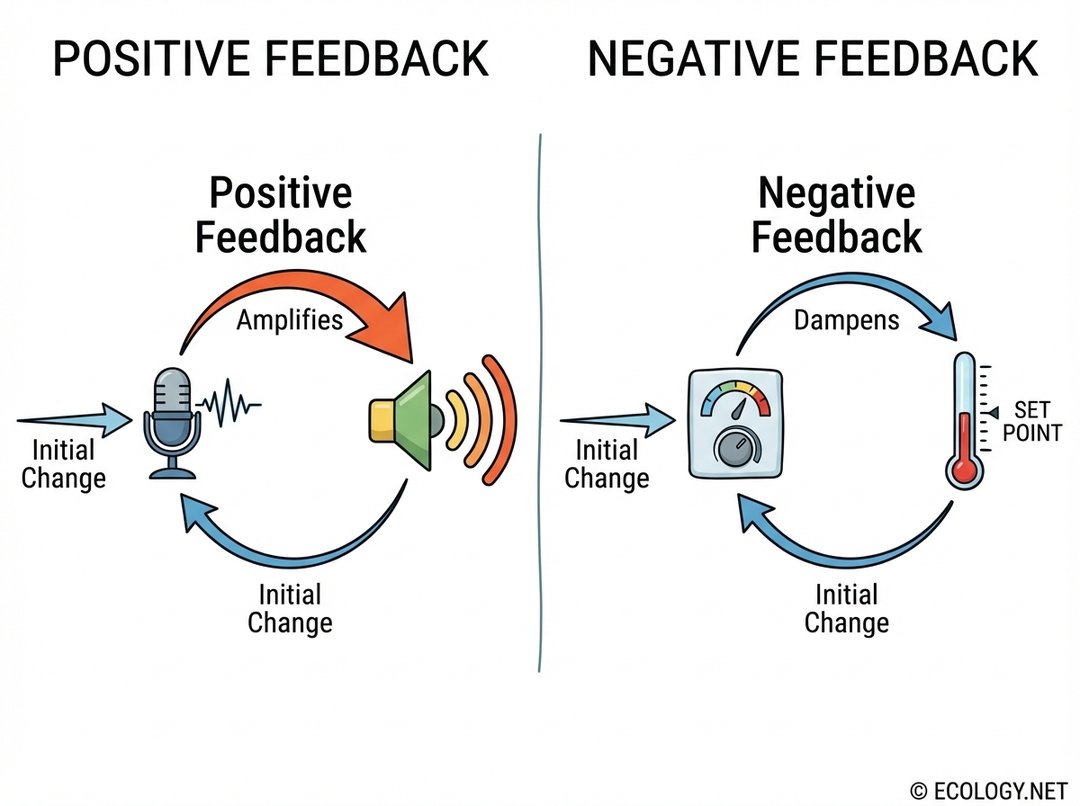

At its core, a feedback loop describes a situation where the output of a system becomes an input that influences the same system. In the context of climate, this means a change in temperature can trigger other changes, which in turn affect the temperature again. These feedbacks come in two primary forms: positive and negative.

Positive Feedbacks: Amplifying the Change

A positive feedback loop amplifies an initial change. Think of it like the screeching sound of a microphone placed too close to a speaker. A small sound enters the microphone, gets amplified, comes out of the speaker, goes back into the microphone, and gets amplified again, quickly spiraling into a loud, uncontrolled noise. In the climate system, a positive feedback means that an initial warming leads to further warming, or an initial cooling leads to further cooling.

These loops are often what concern scientists most, as they can accelerate climate change beyond what might be expected from direct greenhouse gas emissions alone. They can create a self-reinforcing cycle, making it harder to reverse the initial trend.

Negative Feedbacks: Dampening the Change

Conversely, a negative feedback loop works to dampen or counteract an initial change, bringing the system back towards a state of equilibrium. A classic example is a thermostat in a house. When the temperature rises above a set point, the thermostat turns on the air conditioning, cooling the house down. When it drops too low, it turns on the heater. The system actively works to maintain a stable temperature. In the climate, a negative feedback means an initial warming leads to processes that promote cooling, or an initial cooling leads to processes that promote warming.

These natural regulatory mechanisms are vital for maintaining the planet’s habitability, but their capacity to counteract large, rapid changes is limited.

This image introduces the fundamental concepts of positive and negative climate feedbacks, visually distinguishing how they amplify or dampen initial changes, as explained in the ‘The Basics: Positive and Negative Feedbacks’ section.

Key Positive Climate Feedbacks: Accelerators of Warming

While both types of feedbacks exist, many of the most impactful climate feedbacks currently at play are positive, meaning they are accelerating the warming trend. Understanding these is crucial for predicting future climate scenarios.

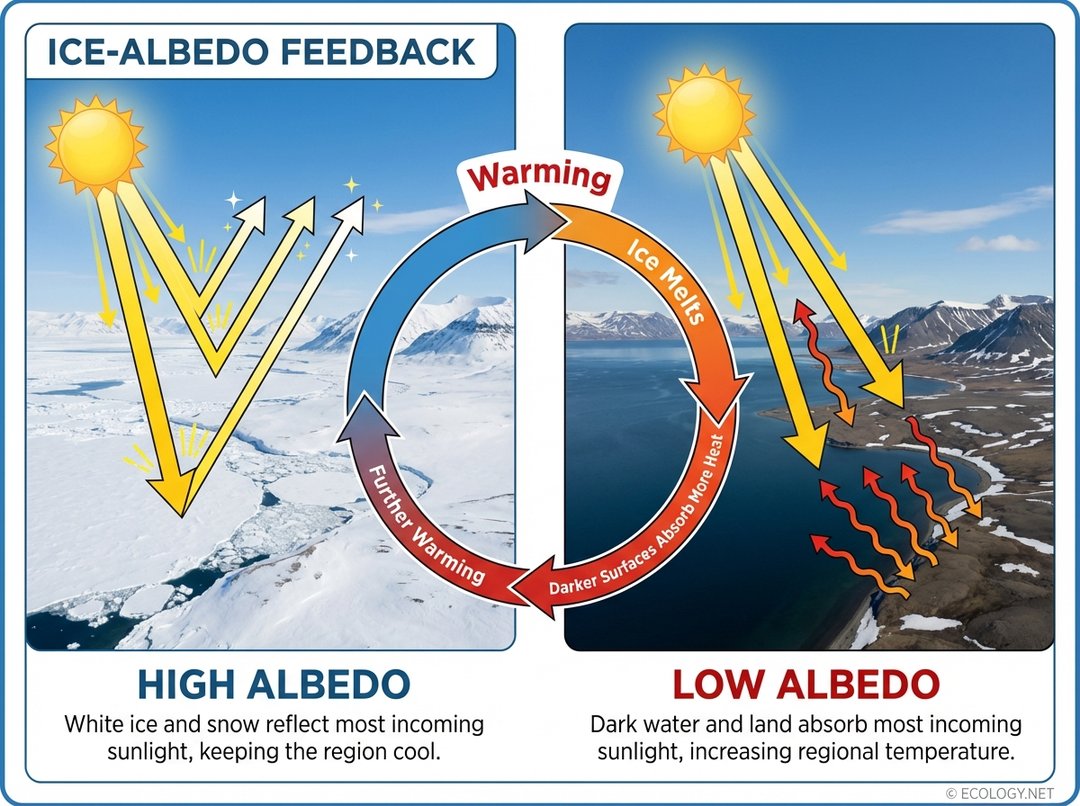

The Ice-Albedo Feedback Loop

One of the most well-known and powerful positive feedbacks is the ice-albedo feedback. Albedo refers to the reflectivity of a surface. Bright surfaces, like ice and snow, have a high albedo, reflecting a large portion of incoming sunlight back into space. Darker surfaces, like open ocean water or bare land, have a low albedo, absorbing more sunlight and converting it into heat.

Here is how the loop works:

- Initial Warming: Global temperatures rise, perhaps due to increased greenhouse gases.

- Ice Melts: This warming causes ice and snow cover, particularly in the Arctic and Antarctic, to melt.

- Darker Surfaces Exposed: As ice melts, it exposes the darker ocean water or land beneath.

- Increased Heat Absorption: These darker surfaces absorb more solar radiation instead of reflecting it.

- Further Warming: The increased absorption of heat leads to even higher temperatures, which in turn causes more ice to melt, perpetuating the cycle.

This feedback is particularly concerning in the Arctic, where warming is occurring at a rate significantly faster than the global average, often referred to as Arctic amplification.

This image visually explains the ‘Ice-Albedo Feedback’, one of the most crucial positive climate feedbacks, by contrasting how reflective ice and snow are compared to darker land and ocean surfaces, and how melting accelerates warming.

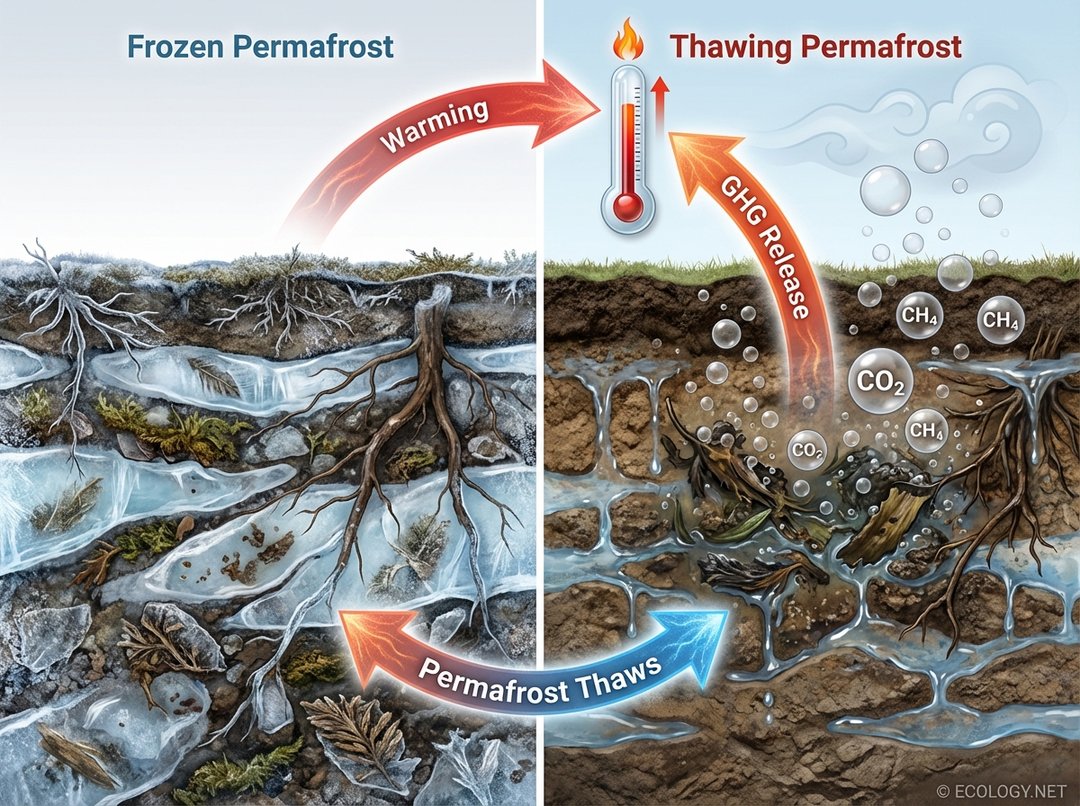

Permafrost Thaw Feedback

Permafrost is ground that has remained frozen for at least two consecutive years, often for thousands of years. Vast areas of permafrost exist in the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions, storing immense quantities of ancient organic matter, such as dead plants and animals, frozen within its layers. This organic matter contains carbon and methane.

The permafrost thaw feedback operates as follows:

- Initial Warming: Rising global temperatures cause permafrost to thaw.

- Organic Matter Decomposes: As the ground thaws, microbes become active and begin to decompose the previously frozen organic matter.

- Greenhouse Gas Release: This decomposition releases potent greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), into the atmosphere. Methane is a particularly powerful greenhouse gas, with a much higher warming potential than CO2 over a shorter timeframe.

- Increased Warming: The released CO2 and CH4 further enhance the greenhouse effect, leading to even higher global temperatures, which in turn causes more permafrost to thaw.

This feedback loop represents a significant potential “tipping point” in the climate system, as the amount of carbon stored in permafrost is estimated to be twice the amount currently in the atmosphere.

This image illustrates the ‘Permafrost Thaw Feedback’, a critical positive feedback where thawing permafrost releases potent greenhouse gases, further accelerating global warming, as described in the article.

Water Vapor Feedback

Water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas in Earth’s atmosphere. Unlike CO2, which is directly emitted by human activities, water vapor concentrations are largely controlled by temperature. This creates a powerful positive feedback:

- Initial Warming: As the Earth’s atmosphere warms, it can hold more water vapor.

- Increased Water Vapor: More water evaporates from oceans and land, increasing the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere.

- Enhanced Greenhouse Effect: Water vapor is a potent greenhouse gas, so its increase further traps heat.

- Further Warming: This additional trapped heat leads to even higher temperatures, which in turn allows the atmosphere to hold even more water vapor.

This feedback significantly amplifies the warming caused by other greenhouse gases like CO2.

Forest Fire Feedback

Another emerging positive feedback involves forest fires. As temperatures rise and droughts become more frequent and intense, forests become drier and more susceptible to large-scale wildfires. These fires release vast amounts of CO2 and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, contributing to further warming. Additionally, the destruction of forests reduces the planet’s capacity to absorb CO2, further exacerbating the problem. The charred, darker land left behind can also absorb more sunlight, adding another layer to this complex feedback.

Key Negative Climate Feedbacks: Natural Stabilizers

While positive feedbacks often dominate discussions about accelerating climate change, the Earth also possesses natural negative feedbacks that work to stabilize the climate system. However, their capacity to counteract rapid, human-induced warming is limited.

Carbon Fertilization Effect

Plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere during photosynthesis. With increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations, some plants, particularly certain types of trees and crops, can grow more vigorously. This phenomenon is known as the carbon fertilization effect. In theory, this increased plant growth could absorb more CO2 from the atmosphere, acting as a negative feedback:

- Increased CO2: Higher levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

- Enhanced Plant Growth: Plants absorb more CO2, leading to increased biomass.

- Reduced Atmospheric CO2: This increased absorption could potentially slow the rate of CO2 accumulation in the atmosphere.

However, the effectiveness of this feedback is constrained by other factors, such as nutrient availability (especially nitrogen and phosphorus), water availability, and temperature stress. As temperatures rise, the benefits of carbon fertilization can be offset by increased respiration from plants and soils, and by more frequent droughts or heatwaves that stress vegetation.

Ocean Carbon Uptake

The world’s oceans act as a massive carbon sink, absorbing a significant portion of the CO2 emitted by human activities. This process occurs through two main mechanisms:

- Physical Solubility Pump: CO2 dissolves directly into seawater. Colder water can hold more dissolved gas, so the polar oceans are particularly important for this process.

- Biological Pump: Marine organisms, particularly phytoplankton, absorb CO2 for photosynthesis. When these organisms die, their carbon-rich remains can sink to the deep ocean, effectively sequestering carbon.

This absorption of CO2 by the oceans acts as a negative feedback, slowing the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. However, there are critical limitations:

- Saturation: The ocean’s capacity to absorb CO2 is not infinite and can become saturated.

- Ocean Acidification: As the ocean absorbs more CO2, it becomes more acidic, a process known as ocean acidification. This has severe consequences for marine ecosystems, particularly for organisms that build shells or skeletons from calcium carbonate, such as corals and shellfish.

- Warming Waters: As ocean temperatures rise, the solubility of CO2 in water decreases, meaning warmer oceans absorb less CO2, potentially weakening this negative feedback.

Cloud Formation: A Complex Feedback

Clouds represent one of the most complex and uncertain climate feedbacks. Their effect can be both positive and negative, depending on their type, altitude, and location:

- Cooling Effect (Negative Feedback): Low, thick clouds tend to reflect a significant amount of incoming solar radiation back into space, thus having a net cooling effect on the planet. An increase in these types of clouds could act as a negative feedback.

- Warming Effect (Positive Feedback): High, thin clouds, like cirrus clouds, allow most sunlight to pass through to the Earth’s surface but are very effective at trapping outgoing longwave radiation (heat) from the surface. This leads to a net warming effect. An increase in these types of clouds could act as a positive feedback.

Predicting how cloud cover and type will change in a warming world is incredibly challenging, making it a major source of uncertainty in climate models. Slight shifts in cloud properties could have significant implications for global temperatures.

The Interplay of Feedbacks: A Symphony of Change

It is crucial to understand that these feedbacks do not operate in isolation. They are interconnected, forming a complex web of interactions that collectively determine the Earth’s climate response. For instance, the melting of Arctic ice (ice-albedo feedback) can expose permafrost to warmer temperatures, accelerating its thaw (permafrost thaw feedback), which then releases more greenhouse gases, further amplifying the initial warming. This cascading effect highlights the potential for non-linear, rapid changes in the climate system.

The Earth’s climate system is a dynamic, interconnected entity. A change in one component can ripple through the entire system, triggering a series of responses that can either stabilize or destabilize the climate. The balance between positive and negative feedbacks is delicate, and human activities are increasingly tipping that balance towards amplification.

Why Understanding Feedbacks Matters

For policymakers, scientists, and the public alike, comprehending climate feedbacks is paramount. They are not merely academic concepts; they are critical components that dictate the speed and magnitude of future climate change. Ignoring them would lead to severe underestimations of future warming and its impacts.

- Accurate Projections: Climate models must accurately represent these feedbacks to provide reliable projections of future temperatures, sea level rise, and extreme weather events.

- Tipping Points: Positive feedbacks increase the risk of crossing “tipping points,” thresholds beyond which certain changes become irreversible, even if greenhouse gas emissions are reduced. Examples include the complete collapse of major ice sheets or widespread permafrost thaw.

- Urgency of Action: The existence of strong positive feedbacks underscores the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The longer we wait, the more these feedbacks will kick in, making it exponentially harder to mitigate warming and adapt to its consequences.

Conclusion: Navigating a Feedback-Driven Future

Climate feedbacks are the Earth’s natural amplifiers and dampeners, shaping our planet’s response to both natural and human-induced changes. While negative feedbacks offer some natural resilience, the powerful positive feedbacks currently at play, such as the ice-albedo effect and permafrost thaw, are accelerating global warming. These processes underscore the interconnectedness of Earth’s systems and the profound implications of human activities. By understanding these intricate loops, we gain a clearer picture of the challenges ahead and the critical importance of informed action to steer our planet towards a more stable and sustainable future.