In the vast tapestry of life, few creatures command as much awe and respect as the carnivores. These apex predators, skilled hunters, and vital components of nearly every ecosystem on Earth, embody power, precision, and an intricate connection to the natural world. Far more than just “meat-eaters,” carnivores represent a diverse group of animals whose very existence shapes the health and balance of their environments. Understanding them is key to comprehending the delicate dance of life on our planet.

What Exactly is a Carnivore?

At its most fundamental, a carnivore is an organism that derives its energy and nutrient requirements from a diet consisting mainly or exclusively of animal tissue, whether through predation or scavenging. This definition, while simple, encompasses an incredible array of life forms, from the microscopic to the majestic. Unlike herbivores, which specialize in consuming plant matter, or omnivores, which have a more varied diet of both plants and animals, carnivores are uniquely adapted for the capture, killing, and consumption of other creatures.

Classifying the Carnivorous World

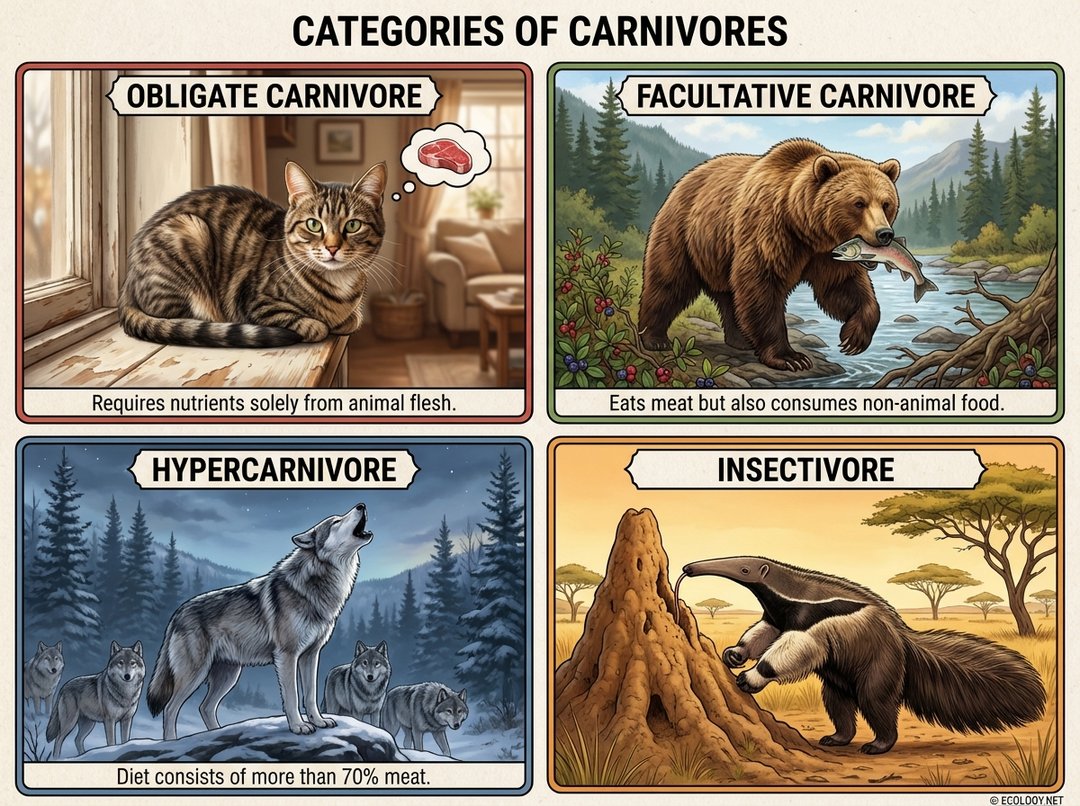

The term “carnivore” itself is broad, and within this category, scientists recognize several distinctions based on dietary specialization:

- Obligate Carnivores (True Carnivores): These animals rely entirely on animal flesh for their nutritional needs. Their digestive systems are specifically evolved to process meat, and they cannot properly digest plant matter. Examples include all species of cats, from the domestic house cat to the mighty tiger, as well as many raptors like eagles and owls.

- Facultative Carnivores: While primarily consuming meat, these animals can also digest and derive nutrients from plant matter. Their diet is flexible, often adapting to seasonal availability or opportunistic foraging. Brown bears, foxes, and even some species of wolves can be considered facultative carnivores, supplementing their meat diet with berries, roots, or insects.

- Hypercarnivores: This term describes carnivores whose diet consists of over 70% meat. Most obligate carnivores fall into this category, but it also includes animals like polar bears, which, despite being technically omnivores, have a diet overwhelmingly dominated by seals.

- Mesocarnivores: These animals have a diet composed of 50-70% meat, with the remainder being plant material, fungi, or insects. Raccoons, badgers, and skunks are classic examples, often displaying opportunistic feeding habits.

- Hypocarnivores: With less than 50% of their diet coming from meat, these are primarily omnivores or even herbivores that occasionally consume meat. Humans, for instance, are hypocarnivores, as are many primates.

- Insectivores: A specialized type of carnivore that primarily feeds on insects and other small invertebrates. Anteaters, aardvarks, and many species of bats are prime examples, showcasing unique adaptations for finding and consuming their tiny prey.

To better visualize these distinctions, consider the varied diets across the animal kingdom:

The Anatomy of a Hunter: Specialized Adaptations

The success of carnivores hinges on a suite of remarkable physical and behavioral adaptations designed for predation. These traits allow them to locate, pursue, capture, and consume their prey efficiently.

Dental and Jaw Structures

Perhaps the most striking adaptation is found in their teeth and jaws. Carnivores possess powerful jaws capable of delivering crushing bites, often equipped with specialized dentition:

- Canines: Long, sharp, and pointed, these teeth are crucial for piercing flesh, gripping prey, and delivering the killing bite.

- Incisors: Smaller, chisel-like teeth at the front of the mouth, used for nipping, grooming, and stripping meat from bones.

- Carnassial Teeth: Found in many mammalian carnivores, these are modified premolars and molars that act like shears, slicing through muscle and tendon with precision.

- Molars: While less prominent than in herbivores, carnivore molars are often sharp and pointed, designed for crushing bones or further processing meat, rather than grinding plant matter.

This specialized dental toolkit stands in stark contrast to the flat, broad molars of herbivores, which are optimized for grinding tough plant fibers.

Claws, Paws, and Locomotion

Beyond teeth, carnivores exhibit a range of adaptations for movement and capture:

- Sharp Claws: Retractable claws in felines, or non-retractable claws in canines, provide grip, aid in climbing, and are formidable weapons for subduing prey.

- Powerful Limbs: Built for speed, agility, or strength, depending on their hunting strategy. Cheetahs possess incredible speed, while bears have immense power for grappling.

- Binocular Vision: Eyes positioned at the front of the head provide excellent depth perception, crucial for tracking moving prey and judging distances.

- Acute Senses: Highly developed senses of smell and hearing often complement their vision, allowing them to detect prey from afar or in low light conditions.

Hunting Strategies and Social Dynamics

Carnivores employ a diverse array of hunting strategies, reflecting their environment, prey, and social structures.

- Solitary Hunters: Many carnivores, such as tigers, leopards, and most felines, hunt alone. This strategy often involves stealth, ambush, and powerful, decisive attacks.

- Pack Hunters: Animals like wolves, African wild dogs, and lions often hunt in groups. This allows them to tackle larger prey, coordinate complex strategies, and increase their success rate. Pack hunting also often involves sophisticated communication and social hierarchies.

- Ambush Predators: These carnivores rely on camouflage and patience, waiting for prey to come within striking distance. Crocodiles, snakes, and many large cats are masters of ambush.

- Pursuit Predators: Built for endurance and speed, these hunters chase down their prey over long distances. Wolves and wild dogs are classic examples, often wearing down their quarry.

The social dynamics of carnivores are as varied as their hunting methods, ranging from the highly territorial and solitary existence of a jaguar to the complex, cooperative family units of a wolf pack.

The Ecological Role of Carnivores: Keystone Species

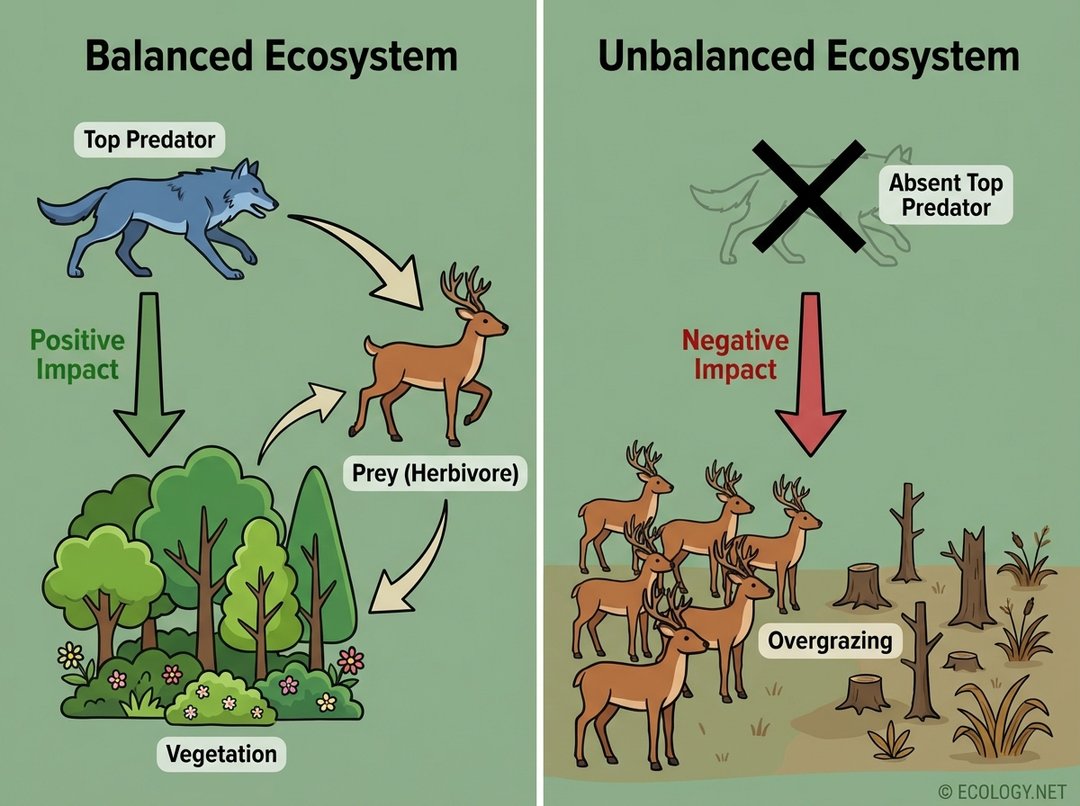

The impact of carnivores extends far beyond simply consuming other animals. They play an indispensable role in maintaining the health, diversity, and balance of ecosystems. Often, they are considered keystone species, meaning their presence or absence has a disproportionately large effect on their environment.

Top-Down Control and Trophic Cascades

Carnivores exert what is known as “top-down control” on ecosystems. By preying on herbivores, they regulate the populations of these plant-eaters. Without this control, herbivore populations can explode, leading to overgrazing and the degradation of vegetation. This ripple effect through different trophic levels is known as a trophic cascade.

For example, the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s led to a remarkable trophic cascade. With wolves preying on elk, elk populations decreased and changed their grazing habits, allowing aspen and willow trees to recover. This, in turn, stabilized riverbanks, created better habitats for beavers and fish, and increased biodiversity throughout the park. It was a powerful demonstration of how a top predator can restore an entire ecosystem.

The image below illustrates this profound impact:

This balance is not just about population numbers. Carnivores also influence the behavior of their prey, making them more vigilant and less likely to concentrate their grazing in one area, further promoting plant diversity.

Scavenging and Disease Control

Beyond active predation, many carnivores also act as scavengers, cleaning up carcasses and preventing the spread of disease. Vultures, hyenas, and even many smaller carnivores play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem hygiene.

Carnivores and Humans: Coexistence and Conservation

The relationship between humans and carnivores has historically been complex, often marked by conflict due to perceived threats to livestock or human safety. However, a growing understanding of their ecological importance has shifted focus towards conservation and coexistence.

Many large carnivore populations worldwide face significant threats, including:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: As human populations expand, natural habitats are destroyed or broken into smaller, isolated patches, making it difficult for carnivores to find food and mates.

- Prey Depletion: Overhunting by humans can reduce the prey base for carnivores, forcing them into conflict with livestock or leading to starvation.

- Direct Persecution: Carnivores are often hunted or poisoned due to fear, retaliation for livestock depredation, or for their fur and body parts.

- Climate Change: Shifting weather patterns and extreme events can disrupt ecosystems, affecting prey availability and habitat suitability for carnivores.

Conservation efforts are crucial and often involve a multi-faceted approach:

- Protected Areas: Establishing national parks and wildlife reserves provides safe havens for carnivore populations.

- Corridors: Creating wildlife corridors helps connect fragmented habitats, allowing animals to move safely between areas.

- Community Engagement: Working with local communities to implement non-lethal methods of livestock protection, such as guard dogs, improved fencing, and compensation schemes, can reduce human-wildlife conflict.

- Anti-Poaching Measures: Strict enforcement and monitoring are essential to combat illegal hunting and trade.

- Research and Monitoring: Understanding carnivore populations, movements, and behaviors is vital for effective conservation strategies.

Conclusion

Carnivores are not merely fascinating creatures; they are indispensable architects of healthy ecosystems. From the smallest insectivore to the largest apex predator, their adaptations, hunting prowess, and ecological roles are a testament to the intricate beauty and balance of the natural world. Protecting these magnificent animals is not just about preserving a species; it is about safeguarding the very fabric of life on Earth, ensuring the resilience and biodiversity of our shared planet for generations to come.