Imagine a tiny, invisible speck of pollution in a vast ocean. Now, imagine that speck growing larger and more potent as it moves through the intricate web of life, eventually landing in the very creatures we admire, or even on our dinner plates. This powerful, often unseen process is known as biomagnification, a critical ecological phenomenon that dictates how certain environmental contaminants become increasingly concentrated at higher levels of a food chain.

Understanding biomagnification is not just for scientists; it is essential for anyone who cares about the health of our planet and its inhabitants, including ourselves. It explains why seemingly minor pollution can have devastating, far-reaching consequences for entire ecosystems.

What is Biomagnification? The Escalation of Toxins

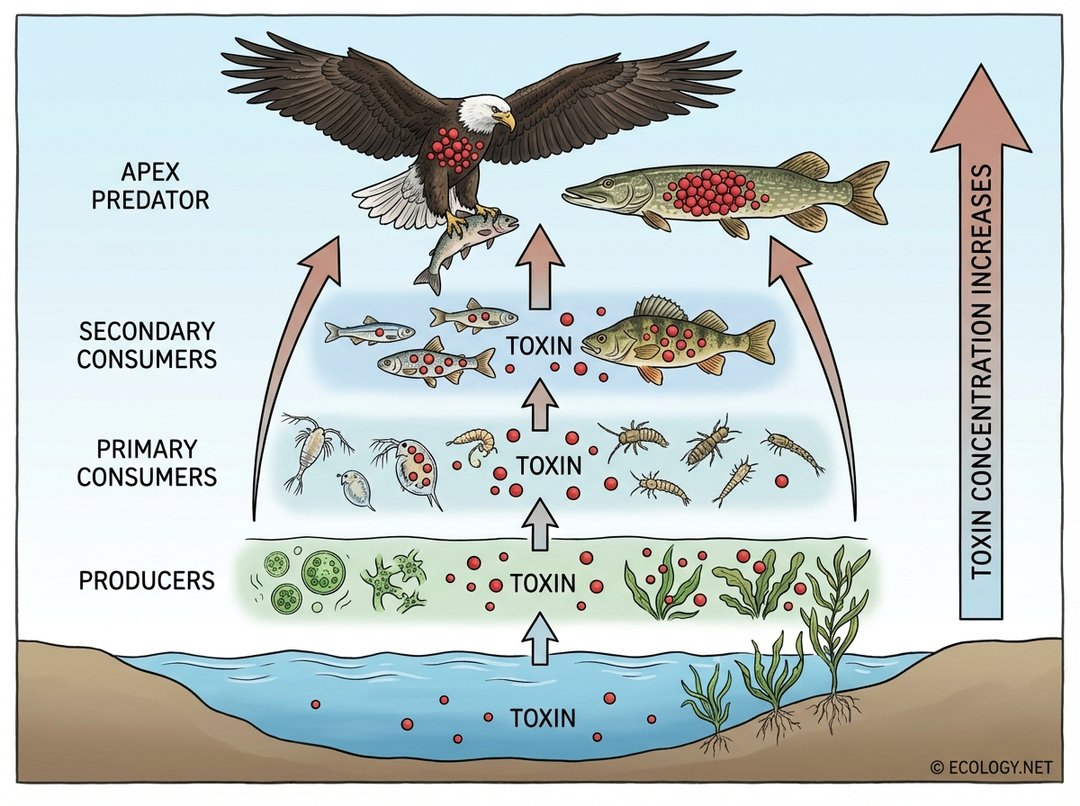

At its core, biomagnification describes the process by which the concentration of a toxin increases in organisms at successively higher trophic levels in a food chain. Think of it as a biological amplifier. A small amount of a persistent pollutant absorbed by a tiny organism at the bottom of the food chain becomes a much larger, more significant amount in the predator that consumes many of those smaller organisms, and even larger in the predator that consumes those predators.

This is distinct from bioaccumulation, which refers to the buildup of a substance, such as a pesticide or other chemical, in an individual organism over its lifetime. While bioaccumulation happens within a single organism, biomagnification specifically refers to the increase in concentration across different trophic levels of a food chain.

The journey of a toxin through an ecosystem is often depicted as an upward climb, with each step representing a new level of concentration. From microscopic algae to majestic apex predators, the impact of these substances intensifies.

The Mechanics Behind the Magnification

Why do some substances biomagnify while others do not? The answer lies in a combination of their chemical properties and the dynamics of energy transfer within ecosystems.

- Persistence: For a substance to biomagnify, it must be persistent, meaning it does not easily break down in the environment or within living organisms. Many synthetic chemicals, like certain pesticides, are designed to be stable, which unfortunately contributes to their longevity in ecosystems.

- Lipid Solubility: Many biomagnifying toxins are fat-soluble (lipophilic). This means they readily dissolve in fats and oils rather than water. When an organism ingests these toxins, they tend to be stored in fatty tissues instead of being excreted. As a predator consumes prey, it also consumes the accumulated fat-soluble toxins.

- Low Excretion Rates: Organisms often lack efficient metabolic pathways to break down or excrete these specific toxins. Consequently, the toxins remain in the body, accumulating over time.

- Energy Transfer Inefficiency: As energy flows up a food chain, only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next. This means a large biomass of lower-trophic-level organisms is required to support a smaller biomass of higher-trophic-level organisms. When a predator consumes many prey items, it ingests all the accumulated toxins from each of those prey, leading to a concentrated dose.

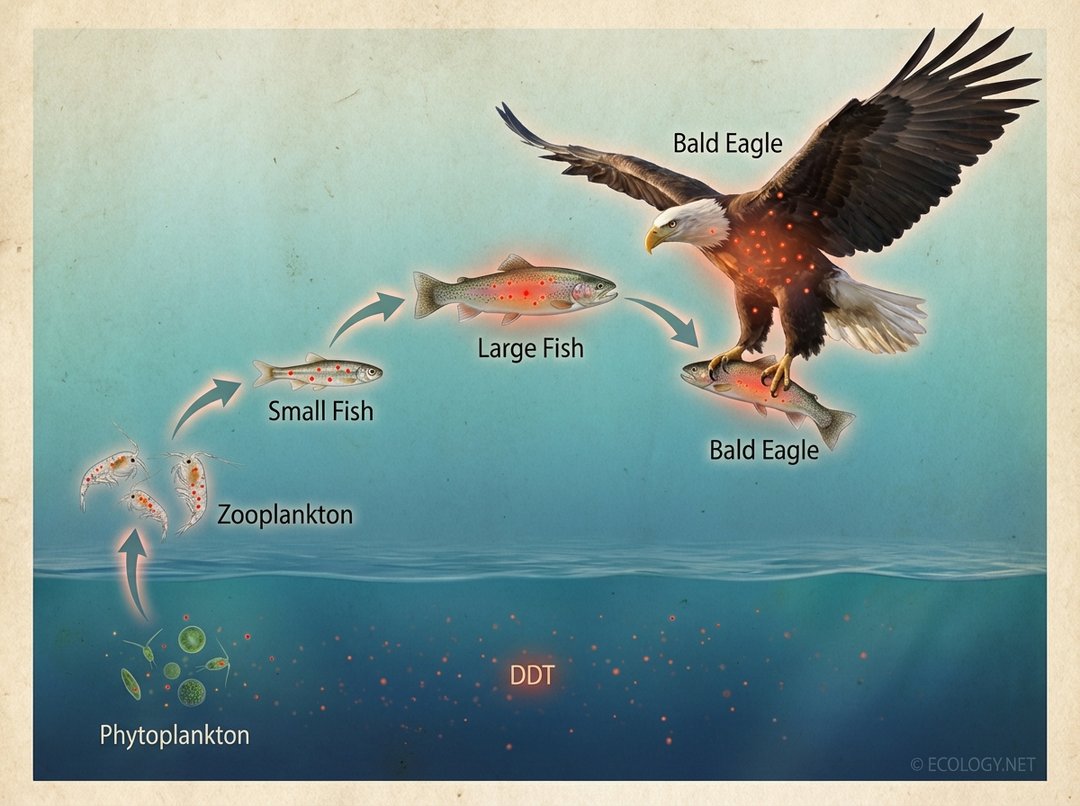

A Classic Example: DDT and the Bald Eagle

Perhaps the most famous and impactful example of biomagnification involves the pesticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and its devastating effects on bird populations, particularly the bald eagle, the national bird of the United States.

DDT was widely used as an insecticide from the 1940s to the 1960s, lauded for its effectiveness in controlling agricultural pests and disease-carrying insects like mosquitoes. However, its persistence and lipid solubility meant it did not disappear after application.

The DDT would wash into waterways, where it was absorbed by tiny phytoplankton. Zooplankton would then consume the phytoplankton, accumulating DDT. Small fish would eat the zooplankton, and larger fish would eat the small fish, each step up the aquatic food chain leading to a higher concentration of the pesticide in their tissues. Finally, apex predators like bald eagles, ospreys, and peregrine falcons would consume large quantities of these contaminated fish.

The high concentrations of DDT in these birds did not directly kill them in most cases. Instead, it interfered with their calcium metabolism, causing them to lay eggs with dangerously thin shells. These fragile eggs would often break during incubation, leading to widespread reproductive failure and a dramatic decline in bird of prey populations. The bald eagle, once abundant, faced extinction. The scientific understanding of biomagnification, largely driven by Rachel Carson’s seminal book “Silent Spring,” led to the ban of DDT in the United States in 1972, a crucial step in the recovery of these iconic species.

Other Notorious Magnifiers: Common Biomagnifying Substances

DDT is just one example. Many other substances exhibit biomagnification, posing ongoing threats to ecosystems and human health.

- Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs): These industrial chemicals were once widely used in electrical equipment, coolants, and hydraulic fluids. Like DDT, PCBs are persistent, fat-soluble, and biomagnify, leading to reproductive issues, immune system suppression, and developmental problems in wildlife, particularly marine mammals and polar bears.

- Heavy Metals:

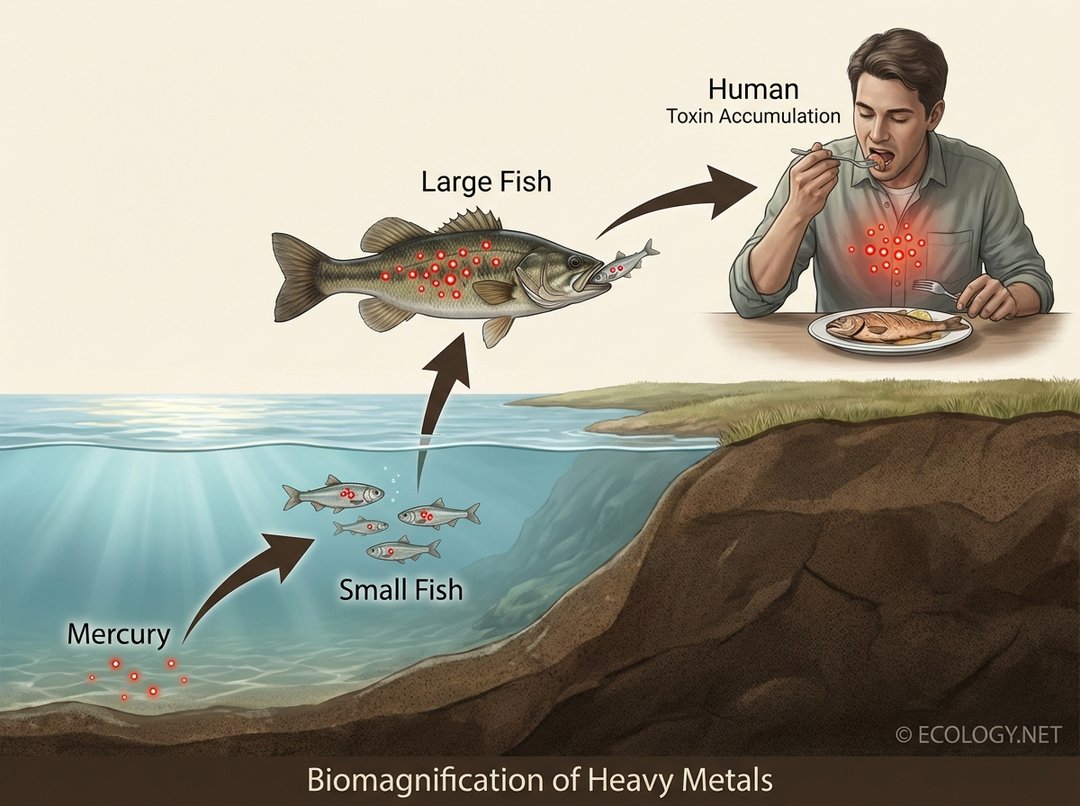

- Mercury: Released into the environment from natural sources like volcanoes and human activities such as coal burning and gold mining, mercury is transformed into highly toxic methylmercury by bacteria in aquatic environments. Methylmercury biomagnifies efficiently through aquatic food chains, posing a significant risk to fish-eating birds, mammals, and humans.

- Lead and Cadmium: While less prone to biomagnification than mercury, these heavy metals can still accumulate in food chains, particularly in terrestrial environments, leading to neurological and kidney damage in affected organisms.

- Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): Often called “forever chemicals,” PFAS are a group of synthetic chemicals found in countless consumer and industrial products. They are extremely persistent and have been shown to biomagnify in some food chains, raising concerns about their long-term health effects on wildlife and humans.

Implications for Human Health: Toxins in Our Food

Humans are not immune to the effects of biomagnification. As apex consumers in many food chains, we are particularly vulnerable to accumulating high concentrations of these persistent toxins through our diet.

The most common concern for human health related to biomagnification is the consumption of fish contaminated with methylmercury. Large, long-lived predatory fish, such as tuna, swordfish, shark, and king mackerel, are at the top of their aquatic food chains and therefore tend to have the highest levels of mercury. Regular consumption of these fish can lead to mercury accumulation in the human body, which can cause neurological damage, developmental problems in children, and other health issues.

Health advisories are often issued to guide consumers, especially pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children, on safe fish consumption limits to minimize mercury exposure. Similar concerns exist for other biomagnifying compounds found in various food sources, highlighting the interconnectedness of environmental health and human well-being.

Broader Ecological Consequences

Beyond individual organisms, biomagnification has profound impacts on entire ecosystems:

- Top Predator Vulnerability: Apex predators are disproportionately affected. Their populations can decline dramatically due to reproductive failure, weakened immune systems, or direct toxicity, leading to imbalances in the food web.

- Biodiversity Loss: The decline of key species can trigger cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, potentially leading to the loss of other species and reduced overall biodiversity.

- Ecosystem Instability: When top predators are removed or severely impacted, their prey populations can explode, leading to overgrazing or other disruptions that destabilize the entire ecosystem.

- Reduced Ecosystem Services: A compromised ecosystem may be less able to provide essential services like clean water, pollination, and pest control.

Mitigation and Solutions: Addressing the Root Cause

Addressing biomagnification requires a multi-faceted approach, focusing on preventing the release of these harmful substances into the environment in the first place.

- Source Reduction: The most effective strategy is to stop or significantly reduce the production and release of persistent, biomagnifying chemicals. This involves developing safer alternatives and implementing stricter industrial regulations.

- Regulation and Policy: International treaties and national laws, like the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), aim to ban or restrict the production and use of the most dangerous biomagnifying chemicals.

- Waste Management: Proper disposal and treatment of industrial and domestic waste are crucial to prevent contaminants from entering ecosystems.

- Consumer Awareness and Choices: Informed consumers can make choices that reduce their exposure and support sustainable practices. This includes understanding fish consumption advisories and choosing products free from known harmful chemicals.

- Research and Monitoring: Continued scientific research helps identify new biomagnifying threats, understand their pathways, and develop effective mitigation strategies. Environmental monitoring programs track contaminant levels in wildlife and ecosystems, providing vital data for policy decisions.

Conclusion: A Call for Ecological Awareness

Biomagnification serves as a powerful reminder of the intricate connections within our natural world and the far-reaching consequences of human activities. It illustrates how pollutants, even in minute quantities, can become concentrated threats to life at the top of the food chain, including humans.

By understanding this ecological principle, we gain a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance of ecosystems and the importance of responsible environmental stewardship. Protecting our planet from biomagnifying toxins requires a collective effort: from policymakers enacting stringent regulations to industries developing greener alternatives, and from individuals making conscious choices about their consumption. Only through such concerted action can we safeguard the health of our ecosystems and ensure a safer, healthier future for all living beings.