Imagine a place on Earth so rich in unique life that it acts as a living museum, yet simultaneously faces such immense threats that its very existence hangs by a thread. These are biodiversity hotspots, critical regions that harbor an extraordinary concentration of species found nowhere else, but are also under severe pressure from human activities. Understanding these vital areas is not just an academic exercise; it is crucial for the future of life on our planet.

What Makes a Hotspot? Defining Earth’s Most Precious Places

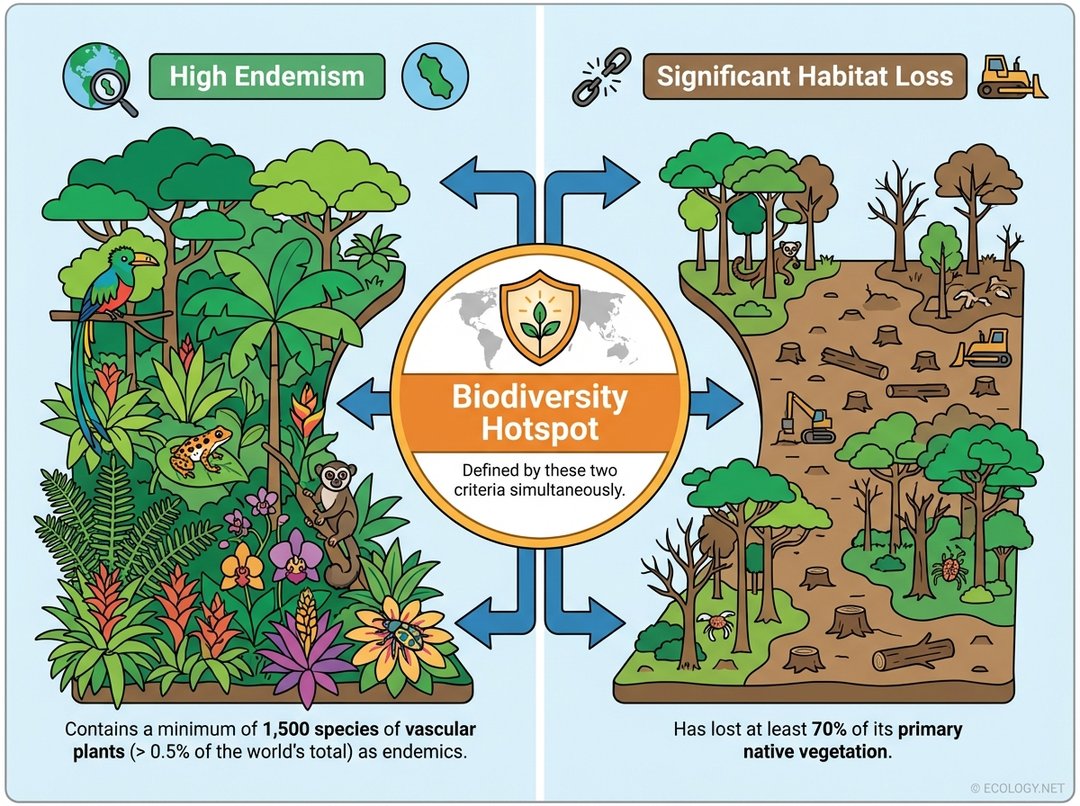

The concept of a biodiversity hotspot was first introduced to identify regions that are both exceptionally rich in species and under extreme threat. To qualify as a biodiversity hotspot, an area must meet two strict criteria:

- High Endemism: It must contain at least 1,500 species of vascular plants as endemics. This means these plant species are native to that specific region and found nowhere else on Earth. This high level of unique life is a hallmark of a hotspot.

- Significant Habitat Loss: It must have lost at least 70 percent of its primary native vegetation. This criterion highlights the urgent need for conservation, as these areas have already suffered massive ecological degradation.

These two conditions together paint a picture of irreplaceable natural heritage teetering on the brink. Hotspots are not merely areas with many species; they are areas with many unique species that are rapidly disappearing.

Why Do Hotspots Matter? The Urgency of Conservation

Biodiversity hotspots cover only about 2.5 percent of Earth’s land surface, yet they are home to more than half of the world’s plant species as endemics and nearly 43 percent of bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species as endemics. This disproportionate concentration of unique life makes their conservation efforts incredibly efficient. Protecting these relatively small areas can safeguard a vast amount of global biodiversity.

Beyond the sheer numbers, hotspots provide invaluable ecosystem services. They regulate climate, purify water, provide fertile soil, and offer potential sources for new medicines and agricultural crops. The loss of biodiversity in these regions can have cascading effects, destabilizing ecosystems globally and impacting human well-being.

The 36 Biodiversity Hotspots Around the Globe

Currently, there are 36 recognized biodiversity hotspots scattered across the continents and oceans. These regions are incredibly diverse in their geography, climate, and the types of species they harbor. From tropical rainforests to Mediterranean shrublands, each hotspot presents a unique ecological tapestry.

Some prominent examples include:

- Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands: Famous for its lemurs, chameleons, and baobab trees, many of which are found nowhere else.

- The Mediterranean Basin: Characterized by its unique flora adapted to dry summers and wet winters, including many aromatic herbs and ancient olive groves.

- The Tropical Andes: Stretching along the western coast of South America, this is the richest and most diverse hotspot on Earth, home to an incredible array of amphibians, birds, and plants.

- The California Floristic Province: Known for its redwood forests, chaparral, and oak woodlands, with a high concentration of endemic plant species.

- Sundaland: Encompassing parts of Southeast Asia, this hotspot is home to orangutans, Sumatran tigers, and a vast diversity of plant life, all under severe threat from deforestation.

Each hotspot tells a story of evolutionary uniqueness and ongoing struggle, emphasizing the global nature of biodiversity conservation.

Diving Deeper into the Ecology of Hotspots

The ecological dynamics within biodiversity hotspots are complex and fascinating, often involving intricate relationships between species and their environment. Understanding these deeper ecological principles is key to effective conservation.

The Role of Keystone Species

Within many ecosystems, certain species play a disproportionately large role in maintaining the structure and function of their environment. These are known as keystone species. Their removal can lead to a dramatic collapse or significant alteration of the ecosystem, even if their biomass is relatively small.

A classic example is the sea otter in kelp forests along the Pacific coast. Sea otters prey on sea urchins, which in turn graze on kelp. Without sea otters, sea urchin populations can explode, leading to overgrazing of kelp forests. These kelp forests are vital habitats for countless marine species, provide food, and protect coastlines. The presence of sea otters ensures the health and productivity of the entire kelp forest ecosystem.

In biodiversity hotspots, the loss of a keystone species can accelerate the decline of an already fragile ecosystem, making their identification and protection a high priority.

Endemic Species and Their Vulnerability

The high endemism that defines a hotspot also makes its species particularly vulnerable. Endemic species, by definition, have restricted geographical ranges. This means they are often highly adapted to specific environmental conditions found only in their native habitat. If that habitat is destroyed or significantly altered, these species have nowhere else to go. They cannot simply migrate to another region because the conditions or resources they need are not present there.

Furthermore, small populations of endemic species are more susceptible to genetic bottlenecks, making them less resilient to diseases or environmental changes. This inherent vulnerability underscores why habitat loss in hotspots is so devastating; it directly threatens species that have no fallback.

Threats to Hotspots: A Multifaceted Challenge

The threats facing biodiversity hotspots are numerous and interconnected, primarily driven by human activities. These include:

- Habitat Destruction and Fragmentation: This is the most significant threat, often due to agriculture, logging, mining, and urban development. Forests are cleared, wetlands are drained, and natural landscapes are converted, leaving species without homes.

- Climate Change: Shifting weather patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and rising temperatures can push species beyond their adaptive limits, especially those with narrow ecological niches.

- Invasive Species: Non-native species introduced to an ecosystem can outcompete native species for resources, prey on them, or introduce diseases, leading to declines in endemic populations.

- Pollution: Contamination of air, water, and soil from industrial activities, agriculture, and waste disposal can directly harm species and degrade their habitats.

- Overexploitation: Unsustainable hunting, fishing, and harvesting of plants can deplete populations faster than they can reproduce, leading to local extinctions.

Addressing these threats requires a comprehensive approach that integrates conservation with sustainable development and local community engagement.

Conservation Efforts and Hope for the Future

Despite the immense challenges, there is hope for biodiversity hotspots. Dedicated conservation organizations, governments, and local communities are working tirelessly to protect these invaluable regions. Strategies include:

- Establishing Protected Areas: Creating national parks, wildlife reserves, and other protected zones helps safeguard critical habitats.

- Restoration Projects: Efforts to reforest degraded areas, restore wetlands, and reintroduce native species can help reverse some of the damage.

- Sustainable Land Use: Promoting farming practices, forestry, and tourism that minimize environmental impact and benefit local communities.

- Policy and Legislation: Implementing strong environmental laws and international agreements to combat illegal wildlife trade and habitat destruction.

- Community Engagement: Empowering local populations to become stewards of their natural heritage, recognizing that their well-being is intrinsically linked to the health of the ecosystem.

The future of biodiversity hotspots depends on a global commitment to these efforts, combining scientific understanding with practical action and a shared vision for a thriving planet.

Guardians of Global Biodiversity

Biodiversity hotspots are more than just geographical locations; they are urgent calls to action. They represent the most critical battlegrounds in the fight to preserve Earth’s rich tapestry of life. By understanding what makes these areas unique, recognizing the threats they face, and supporting dedicated conservation efforts, humanity can play a pivotal role in safeguarding these irreplaceable treasures for generations to come. The health of these hotspots is a barometer for the health of our planet, and their protection is a shared responsibility that benefits all life on Earth.