The Invisible Threat: Unraveling the Mystery of Acid Rain

Imagine rain, not as a refreshing shower, but as a silent, corrosive force slowly eroding our forests, poisoning our lakes, and even dissolving ancient monuments. This is the reality of acid rain, a pervasive environmental challenge that has shaped ecosystems and policies across the globe. Far from being a simple weather phenomenon, acid rain is a complex chemical process with far-reaching consequences, a testament to humanity’s impact on the natural world. Understanding its origins, effects, and solutions is crucial for safeguarding our planet’s delicate balance.

What is Acid Rain? A Chemical Breakdown

To truly grasp acid rain, we must first understand what makes rain acidic. All rain is naturally slightly acidic, with a pH of around 5.6, due to the absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, forming weak carbonic acid. However, when rain’s pH drops below this level, typically to 5.0 or even lower, it is classified as acid rain. The pH scale, ranging from 0 to 14, measures acidity and alkalinity, with 7 being neutral. Each whole number decrease on the pH scale represents a tenfold increase in acidity, making even small drops in pH significant.

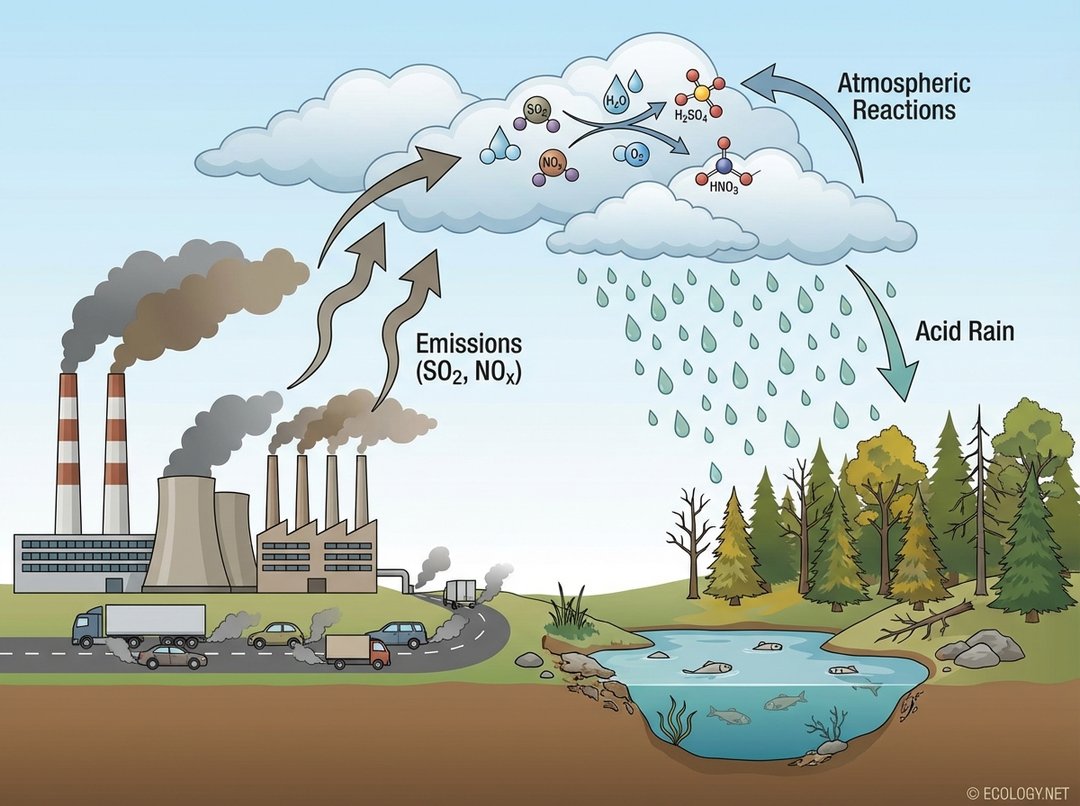

The primary culprits behind this increased acidity are two atmospheric pollutants: sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx). These gases are released into the atmosphere predominantly through human activities:

- Industrial Emissions: Power plants, especially those burning fossil fuels like coal, are major emitters of sulfur dioxide. Factories and smelters also contribute significantly.

- Vehicle Exhaust: Cars, trucks, and other forms of transportation release nitrogen oxides as a byproduct of burning gasoline and diesel.

- Other Sources: Industrial boilers, oil refineries, and even some natural sources like volcanic eruptions can contribute, though human activities are the dominant factor.

Once released, these gases do not immediately fall as acid rain. Instead, they undergo a series of complex chemical reactions in the atmosphere. Sulfur dioxide reacts with oxygen and water to form sulfuric acid, while nitrogen oxides react similarly to form nitric acid. These strong acids then mix with water vapor and other particles, eventually falling to Earth as rain, snow, fog, or even dry particles, collectively known as acid deposition.

The Silent Scourge: How Acid Rain Harms Our World

The impacts of acid rain are pervasive, affecting ecosystems, infrastructure, and even human health. Its insidious nature means that damage often accumulates slowly, making it a challenge to detect until significant harm has occurred.

Aquatic Ecosystems: The Most Vulnerable

Lakes, rivers, and streams are particularly susceptible to acid rain. When acidic precipitation falls into these bodies of water, it lowers their pH, a process known as acidification. Many aquatic organisms have a narrow pH tolerance, and even slight changes can be devastating.

- Fish and Amphibians: Fish eggs may fail to hatch, and adult fish can suffer from physiological stress, leading to reduced growth, reproductive failure, and increased mortality. Species like trout and salmon are highly sensitive. Acidification also releases toxic metals, such as aluminum, from the soil into the water, which can clog fish gills and cause suffocation.

- Invertebrates: Insects, snails, and other aquatic invertebrates, which form the base of the food web, are also severely impacted, disrupting the entire ecosystem.

- “Dead Lakes”: In extreme cases, entire lakes can become so acidic that they are unable to support most forms of life, earning them the grim moniker of “dead lakes.”

Forests: A Slow Decline

Forests, especially those at higher elevations, are also gravely threatened by acid rain. The damage is often a slow, cumulative process, weakening trees over time rather than killing them outright.

- Nutrient Leaching: Acid rain leaches vital nutrients, such as calcium and magnesium, from the soil, depriving trees of essential elements for growth.

- Aluminum Toxicity: Similar to aquatic systems, acid rain mobilizes aluminum in forest soils, which can damage tree roots and impair their ability to absorb water and nutrients.

- Weakened Resistance: Trees stressed by acid rain become more vulnerable to other environmental stressors, including disease, insect infestations, drought, and extreme cold. This can lead to widespread forest decline, characterized by yellowing leaves, sparse foliage, and bare branches.

Soil Health and Agriculture

The soil, the foundation of terrestrial life, also suffers from acid deposition. Acid rain can alter soil chemistry, reducing its fertility and affecting agricultural productivity.

- Nutrient Depletion: Essential plant nutrients are washed away, making soils less fertile.

- Heavy Metal Release: Toxic heavy metals, naturally present in soil, can become soluble and available for uptake by plants, potentially entering the food chain.

- Microbial Impact: Soil microorganisms, vital for nutrient cycling, can be negatively affected, further disrupting ecosystem health.

Material Damage: Buildings and Monuments

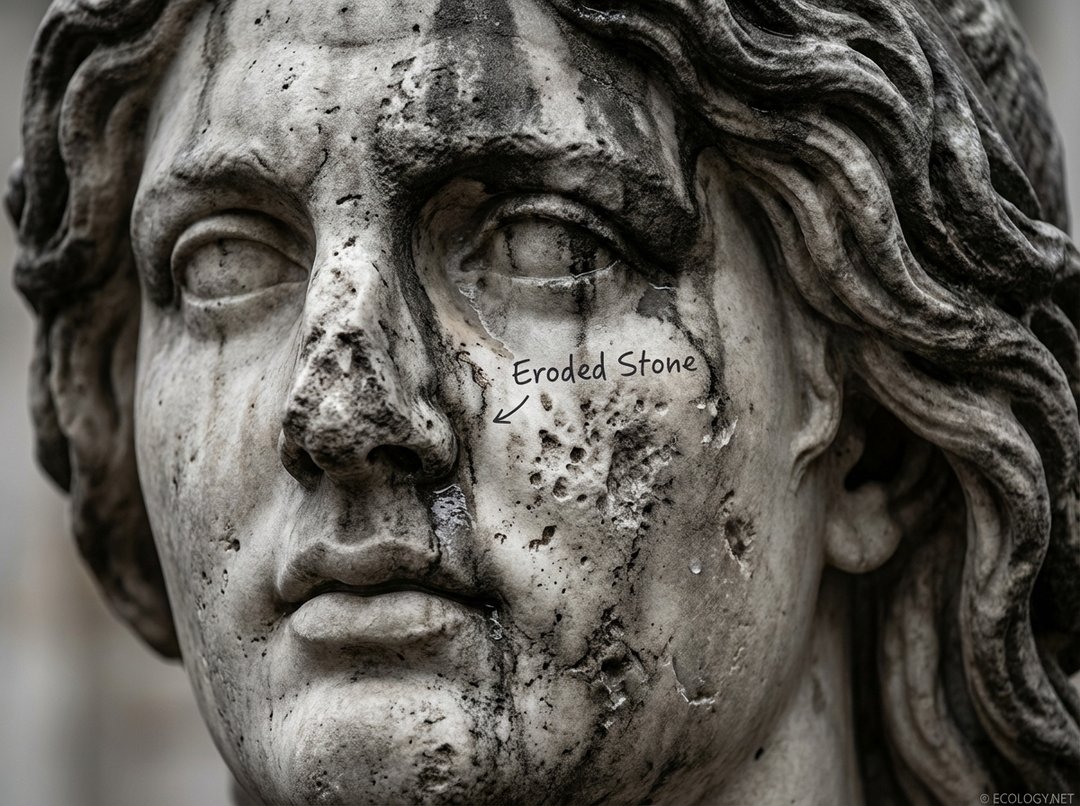

Beyond natural ecosystems, acid rain poses a significant threat to human-made structures, particularly those constructed from limestone, marble, or certain metals. These materials react chemically with the acids, leading to corrosion and erosion.

- Stone Erosion: Historic buildings, statues, and monuments made of calcium carbonate rich stones like marble and limestone are particularly vulnerable. The acids dissolve the stone, causing pitting, blackening, and the loss of intricate details. This damage is irreversible and represents a significant loss of cultural heritage.

- Metal Corrosion: Bridges, fences, and other metal structures can also corrode more rapidly when exposed to acid rain, leading to increased maintenance costs and safety concerns.

Human Health Implications

While acid rain itself does not directly harm humans through skin contact, the pollutants that cause it, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, can have serious health consequences. These gases and the fine particulate matter they form can penetrate deep into the lungs, exacerbating respiratory illnesses like asthma and bronchitis, and contributing to heart and lung disease.

Where Does It Happen? Global and Local Perspectives

Acid rain is not confined to the region where pollutants are emitted. Winds can carry sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides hundreds or even thousands of kilometers away before they are transformed into acids and deposited. This phenomenon, known as transboundary pollution, means that one country’s industrial emissions can become another country’s environmental problem.

Historically, regions in northeastern North America, central and northern Europe, and parts of Asia have been severely affected. The industrial heartlands of these continents, with their high concentrations of power plants and factories, were major sources. While significant progress has been made in some areas, particularly in North America and Europe, rapidly industrializing regions in Asia continue to face substantial challenges from acid rain.

Turning the Tide: Solutions and Mitigation

Addressing acid rain requires a multifaceted approach, combining technological innovation, policy changes, and international cooperation. The good news is that concerted efforts have shown remarkable success in reducing acid rain in many parts of the world.

- Emission Control Technologies:

- Scrubbers: These devices, installed in power plant smokestacks, remove sulfur dioxide from exhaust gases before they are released into the atmosphere.

- Catalytic Converters: Mandatory in most modern vehicles, catalytic converters reduce nitrogen oxide emissions by converting them into less harmful gases.

- Low-NOx Burners: These technologies reduce the formation of nitrogen oxides during combustion in industrial boilers.

- Cleaner Energy Sources: Shifting away from fossil fuels towards renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and hydroelectric power significantly reduces the emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides.

- Policy and Legislation: Landmark legislation, such as the Clean Air Act in the United States, has set limits on emissions and established cap and trade programs, providing economic incentives for industries to reduce pollution.

- International Cooperation: Because of transboundary pollution, international agreements and treaties are vital for addressing acid rain effectively.

- Individual Actions: Reducing personal energy consumption, using public transportation, and supporting policies that promote clean energy can collectively make a difference.

The Future of Acid Rain: Continued Vigilance

While significant strides have been made in combating acid rain in many developed nations, the fight is far from over. New industrialization in other parts of the world means that acid rain remains a persistent threat. Furthermore, the complex interplay between acid rain and other environmental issues, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, necessitates a holistic approach to environmental management.

Continued monitoring of air quality, research into new emission control technologies, and sustained policy efforts are essential. The story of acid rain serves as a powerful reminder of our interconnectedness with the environment and the profound impact our actions can have, both locally and globally. It also offers a hopeful lesson: with collective will and scientific innovation, even widespread environmental damage can be mitigated and reversed.

Conclusion

Acid rain, a consequence of industrial emissions, has left an indelible mark on our planet, from eroding ancient statues to silently devastating aquatic life and forests. Its formation from sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, and its far-reaching effects on ecosystems and infrastructure, underscore the delicate balance of our natural systems. However, the progress made in reducing acid rain in many regions demonstrates the power of human ingenuity and cooperation. By understanding this invisible threat, embracing cleaner technologies, and enacting thoughtful policies, we can continue to protect our environment and preserve its beauty and biodiversity for generations to come.