Understanding Ecological Resistance: How Ecosystems Stand Their Ground

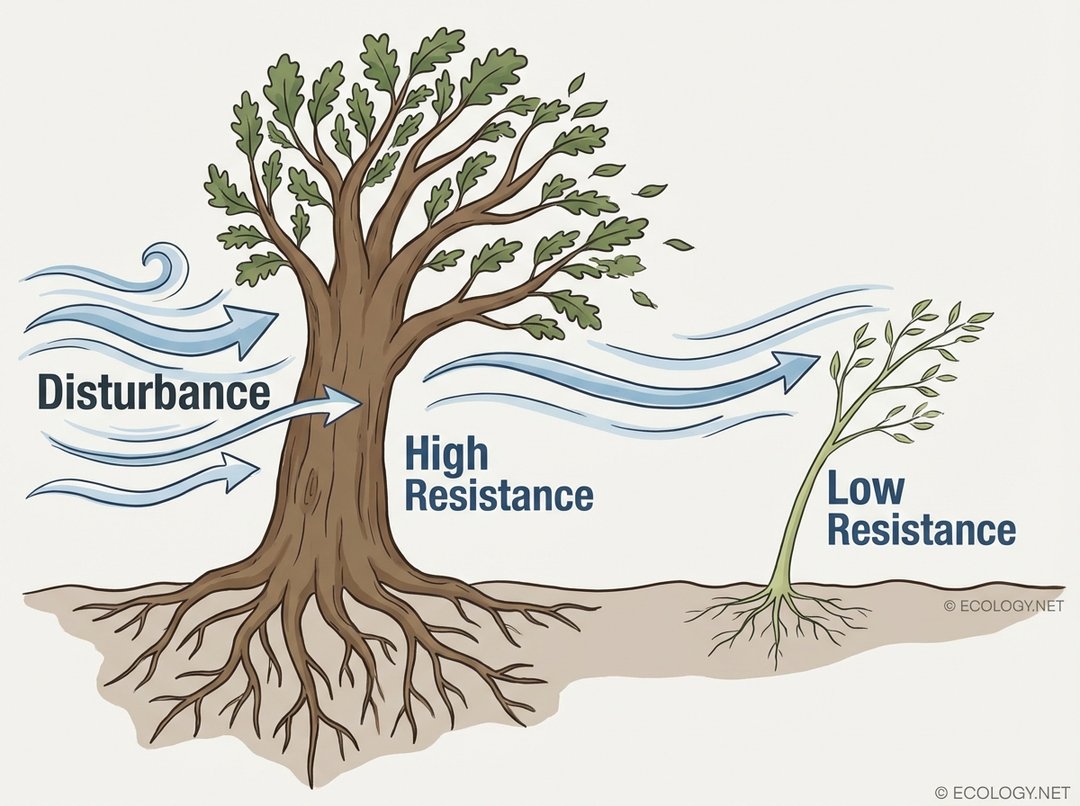

Imagine a mighty oak tree, its roots deeply anchored, its trunk unyielding against a furious storm. Now picture a slender sapling nearby, bending almost to the ground under the same gale. This vivid contrast perfectly encapsulates a fundamental concept in ecology: resistance. In a world increasingly shaped by environmental change and human impact, understanding how ecosystems resist disturbances is more critical than ever.

Ecological resistance is a cornerstone of ecosystem health and stability. It is the ability of an ecosystem, community, or population to remain relatively unchanged when subjected to a disturbance. This remarkable capacity allows nature to absorb shocks, maintain its structure, and continue providing the vital services upon which all life depends.

What Exactly Is Ecological Resistance?

At its heart, ecological resistance describes an ecosystem’s capacity to withstand or oppose change when faced with a disruptive event. Think of it as an ecosystem’s inherent strength or its ability to “push back” against forces that try to alter its state. A highly resistant ecosystem will experience minimal alteration in its species composition, biomass, nutrient cycling, or overall structure following a disturbance.

Consider the analogy of the trees in a storm. The oak tree, with its robust structure and extensive root system, exhibits high resistance. It hardly changes its form despite the strong winds. The sapling, on the other hand, demonstrates low resistance; it is significantly altered by the same disturbance, bending severely and potentially suffering damage.

This concept is crucial because disturbances are an inevitable part of natural systems. They can range from natural events like wildfires, floods, and insect outbreaks to human induced pressures such as pollution, habitat fragmentation, and climate change. An ecosystem’s resistance determines how well it can absorb these impacts without collapsing or undergoing irreversible shifts.

Resistance Versus Related Concepts

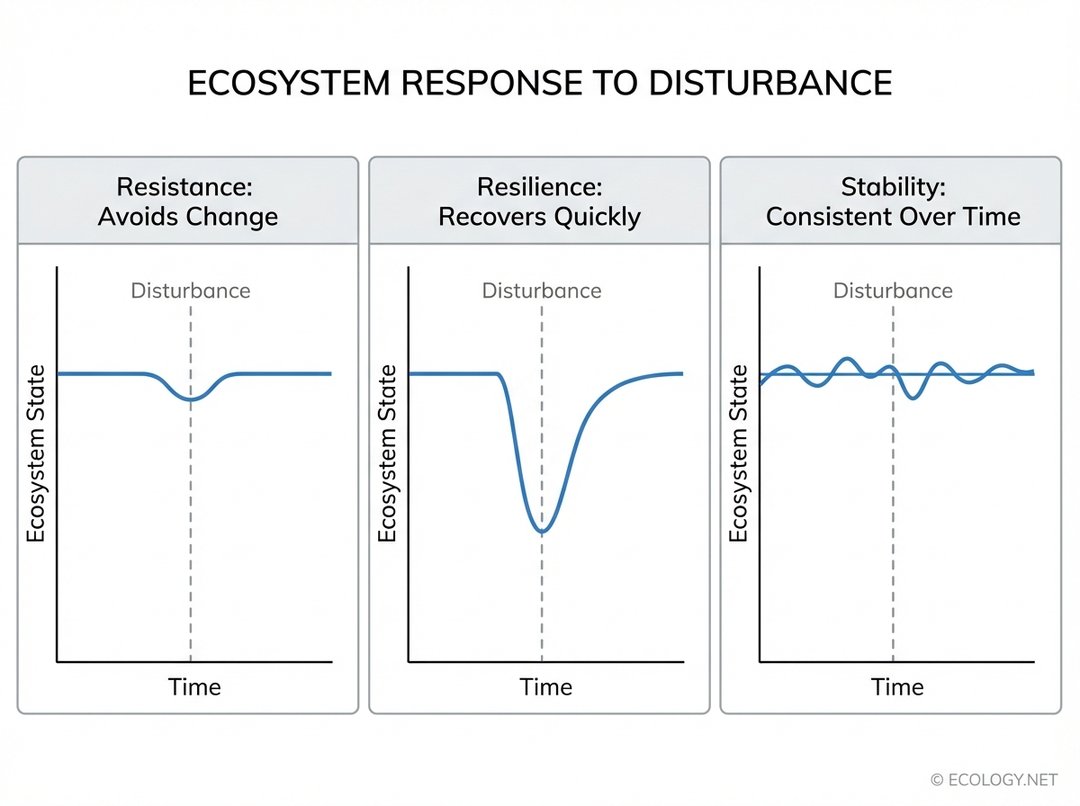

Ecological resistance is often discussed alongside other important concepts like resilience and stability. While interconnected, they describe distinct aspects of an ecosystem’s response to disturbance.

- Resistance: As we have explored, this is the ability to avoid change in the face of a disturbance. It is about staying the same.

- Resilience: This refers to the speed and extent to which an ecosystem recovers to its original state after being disturbed. An ecosystem might be highly disturbed (low resistance) but recover very quickly (high resilience).

- Stability: This is a broader term encompassing both resistance and resilience. A stable ecosystem is one that maintains its structure and function over time, often implying a combination of both the ability to resist change and to recover effectively if change occurs.

To visualize these differences, imagine a ball in a valley. Resistance is how hard you have to push the ball to get it out of the valley. Resilience is how quickly the ball rolls back to the bottom if it is pushed out. Stability is the overall tendency of the ball to remain in or return to the valley.

Understanding these distinctions is vital for ecologists and conservationists. A forest that resists a pest outbreak is different from one that is devastated but quickly regrows. Both might be considered stable in the long term, but their mechanisms for achieving that stability differ significantly.

Factors Influencing Ecological Resistance

What makes one ecosystem more resistant than another? Several key factors contribute to an ecosystem’s ability to withstand disturbance:

-

Biodiversity:

- Species Diversity: Ecosystems with a greater variety of species often exhibit higher resistance. This is due to functional redundancy, where multiple species perform similar ecological roles. If one species is negatively affected by a disturbance, others can compensate, maintaining overall ecosystem function. For example, a diverse plant community might have species with varying tolerances to drought, ensuring some productivity even in dry conditions.

- Genetic Diversity: Within a single species, a wide range of genetic traits can also confer resistance. A population with high genetic diversity is more likely to contain individuals with traits that allow them to survive a new disease or environmental stress, ensuring the population’s persistence.

- Ecosystem Complexity and Structure: Intricate food webs, diverse habitats, and complex physical structures (like old growth forests with multiple canopy layers) can buffer against disturbances. These complexities provide more pathways for energy flow and more refugia for organisms, making the system less vulnerable to single points of failure.

- Resource Availability: Ecosystems with abundant and stable resources (water, nutrients, light) tend to be more resistant. Organisms in such systems are less stressed and better equipped to cope with additional pressures.

- Disturbance History: Ecosystems that have historically experienced certain types of disturbances may evolve adaptations that increase their resistance to those specific events. For instance, fire adapted forests often have trees with thick bark or cones that open only with heat, making them resistant to low intensity fires.

- Trophic Structure: The organization of feeding relationships within an ecosystem can play a role. Strong trophic cascades or highly specialized predator prey relationships can sometimes make an ecosystem more vulnerable if a key species is removed. Conversely, robust food webs with many generalist feeders can enhance resistance.

Types of Disturbances Ecosystems Face

Disturbances come in many forms, each testing an ecosystem’s resistance in unique ways. They can be categorized broadly:

-

Natural Disturbances:

- Abiotic: Wildfires, floods, droughts, hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, landslides, extreme temperature events.

- Biotic: Insect outbreaks, disease epidemics, invasive species introductions.

-

Anthropogenic Disturbances (Human Induced):

- Pollution (air, water, soil)

- Habitat destruction and fragmentation (deforestation, urbanization)

- Climate change (altered temperature and precipitation patterns, sea level rise)

- Overexploitation of resources (overfishing, unsustainable logging)

- Introduction of non native species

The nature, intensity, frequency, and spatial extent of a disturbance all influence how an ecosystem resists it. A small, localized fire might be resisted effectively, while a massive, intense wildfire could overwhelm even a highly resistant system.

Examples of Resistance in Action

Real world examples vividly illustrate the concept of ecological resistance:

- Forests Resisting Insect Outbreaks: A diverse forest with many tree species is often more resistant to a specific insect pest than a monoculture plantation. If the pest targets one tree species, others remain unaffected, maintaining the forest’s overall structure and function.

- Coral Reefs and Thermal Stress: Some coral species possess genetic variations that allow them to tolerate higher water temperatures, making certain reefs more resistant to bleaching events than others. These resistant corals can act as refugia, helping to seed recovery in surrounding areas.

- Grasslands Resisting Drought: Grasslands with a mix of deep rooted and shallow rooted species, or those with a high diversity of functional plant types, tend to be more resistant to drought. Different species can access water from various soil depths, ensuring some plant cover and productivity persists.

- Wetlands Filtering Pollutants: Healthy wetlands, with their diverse plant communities and microbial life, can exhibit high resistance to moderate levels of nutrient pollution. The plants absorb excess nutrients, and microbes break down contaminants, preventing widespread ecological damage.

The Importance of Resistance for a Sustainable Future

The ability of ecosystems to resist change is not merely an academic concept; it has profound implications for human well being and the future of our planet.

- Maintaining Ecosystem Services: Resistant ecosystems continue to provide essential services like clean air and water, pollination, soil formation, and climate regulation even when faced with stress. For example, a resistant forest continues to sequester carbon and produce oxygen despite a minor pest infestation.

- Protecting Biodiversity: By resisting disturbances, ecosystems help safeguard the species within them, preventing local extinctions and preserving the genetic library of life.

- Economic Stability: Industries reliant on natural resources, such as agriculture, fisheries, and forestry, benefit immensely from resistant ecosystems that can withstand environmental shocks, ensuring consistent yields and livelihoods.

- Human Health and Safety: Resistant natural barriers, like coastal mangroves or healthy coral reefs, can protect human communities from storm surges and erosion, demonstrating their direct role in disaster risk reduction.

Measuring and Assessing Resistance

For ecologists, quantifying resistance is a complex but essential task. It typically involves comparing an ecosystem’s state before and after a disturbance, or comparing disturbed areas to undisturbed control areas. Key metrics often include:

- Change in Species Richness or Composition: How many species were lost or gained? Did the dominant species shift?

- Biomass or Productivity: Was there a significant reduction in the total living matter or the rate of energy production?

- Nutrient Cycling Rates: Were processes like nitrogen fixation or decomposition significantly altered?

- Structural Integrity: Did the physical structure of the ecosystem (e.g., canopy height in a forest, reef complexity) remain intact?

Experimental manipulations, where scientists intentionally apply disturbances to controlled plots, are also powerful tools for understanding resistance. Long term monitoring programs are crucial for tracking ecosystem responses over extended periods and across multiple disturbance events.

Enhancing Ecological Resistance

Given the increasing pressures on natural systems, actively working to enhance ecological resistance is a critical conservation strategy. This involves:

- Biodiversity Conservation: Protecting and restoring species diversity and genetic diversity within populations is paramount. This includes establishing protected areas, combating invasive species, and preventing overexploitation.

- Habitat Protection and Restoration: Maintaining large, connected, and intact habitats provides more opportunities for species to move and adapt, increasing overall ecosystem robustness. Restoring degraded habitats can rebuild their inherent resistance.

- Sustainable Resource Management: Practices that minimize human impact, such as sustainable forestry, responsible fishing, and regenerative agriculture, reduce chronic stressors on ecosystems, thereby bolstering their resistance to acute disturbances.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is fundamental to lessening the frequency and intensity of climate related disturbances like extreme heatwaves, droughts, and storms, which can overwhelm even highly resistant systems.

- Reducing Pollution: Minimizing chemical runoff, air pollution, and plastic waste directly reduces stressors that weaken ecosystem health and resistance.

Conclusion

Ecological resistance is a testament to the enduring power of nature. It is the silent strength that allows ecosystems to absorb shocks, maintain their intricate balance, and continue to support life on Earth. From the deep rooted oak standing firm against a gale to a diverse forest shrugging off a pest, the ability to resist change is a vital characteristic of healthy, functioning ecosystems.

As we navigate an era of unprecedented environmental challenges, fostering and protecting ecological resistance must be at the forefront of our conservation efforts. By understanding its mechanisms and actively working to enhance it, we can help ensure that our planet’s natural systems remain robust, vibrant, and capable of sustaining both wildlife and humanity for generations to come.