Beneath our feet lies a world of incredible complexity, a dynamic ecosystem that sustains life on Earth. Among its many fascinating characteristics, one of the most fundamental and impactful is soil texture. Far from being a mere academic concept, soil texture dictates everything from how well plants grow to how water moves through the landscape and even the stability of our infrastructure. Understanding it is key to unlocking the secrets of healthy ecosystems and productive gardens.

What Makes Up Soil Texture? The Building Blocks of Soil

At its core, soil texture refers to the relative proportions of three primary mineral particles: sand, silt, and clay. These particles are essentially tiny fragments of weathered rock, but their differences in size are profound and have monumental consequences for the soil’s behavior.

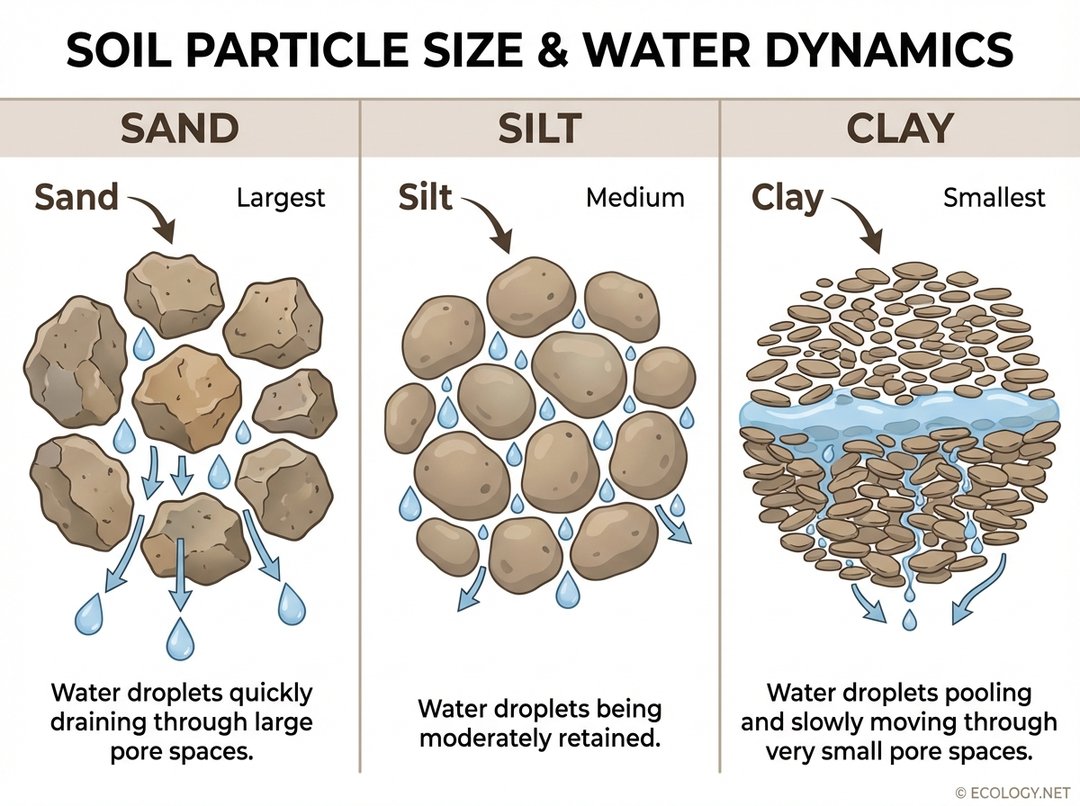

- Sand: These are the largest particles, ranging from 0.05 to 2 millimeters in diameter. Imagine tiny, irregular pebbles. Because of their size, sand particles create large pore spaces between them, allowing water to drain very quickly and air to circulate freely. Think of a beach, where water rapidly disappears into the sand.

- Silt: Medium-sized particles, silt ranges from 0.002 to 0.05 millimeters. They feel smooth and floury when dry, and somewhat slippery when wet. Silt particles are small enough to hold more water than sand, but large enough to allow for moderate drainage and aeration.

- Clay: The smallest of the three, clay particles are less than 0.002 millimeters in diameter. These microscopic particles are often flat and plate-like. Their tiny size means they pack together very tightly, creating extremely small pore spaces. This results in slow water movement, high water retention, and a sticky feel when wet. Clay also has a high surface area, which is crucial for nutrient retention.

The interplay of these three particle sizes determines the soil’s physical properties, influencing everything from water movement to nutrient availability.

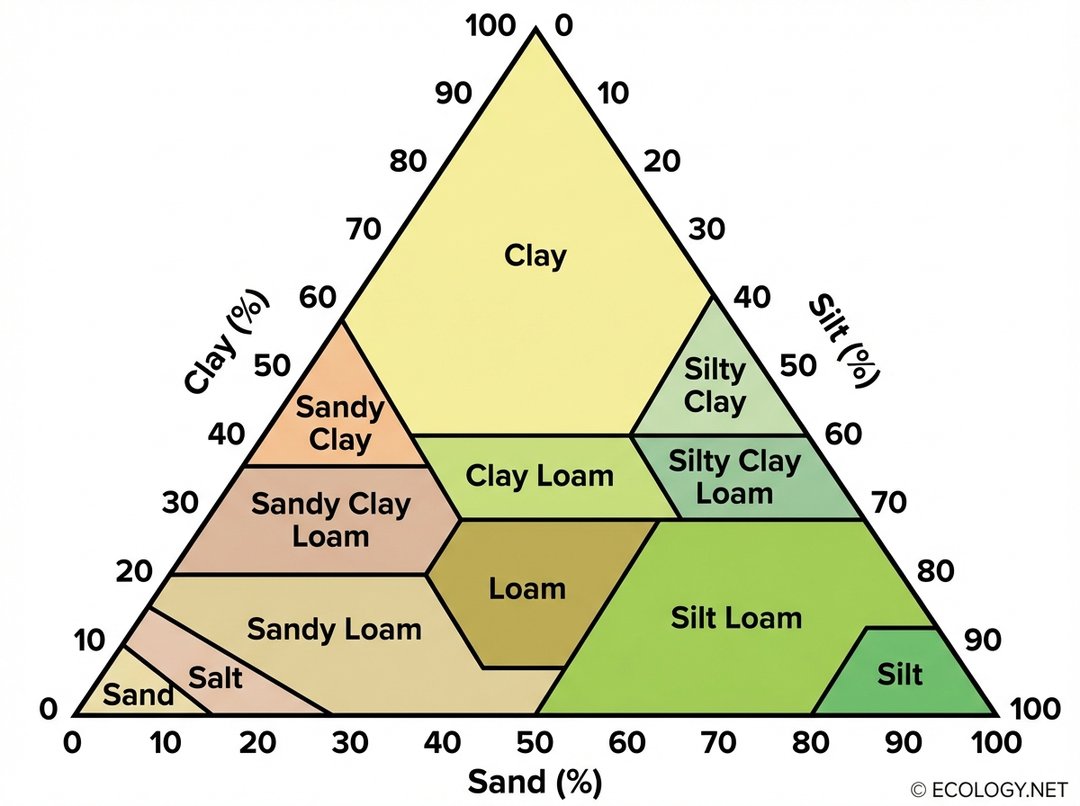

The Soil Texture Triangle: Your Soil’s ID Card

To precisely classify soil based on these proportions, scientists and land managers use a tool called the soil texture triangle. This ingenious diagram allows for a standardized classification of soil into 12 major textural classes, such as “sandy loam,” “silty clay,” or “loam.”

Imagine a triangle where each side represents the percentage of one of the three particle types: sand, silt, and clay. By knowing the percentage of any two components, you can find the intersection point on the triangle, which then reveals the soil’s textural class. For example, a soil with 40% sand, 40% silt, and 20% clay would fall into the “loam” category.

Understanding the Classes

- Sandy Soils: Dominated by sand, these soils drain quickly and warm up fast in spring. Examples include “Sand” and “Loamy Sand.”

- Silty Soils: High in silt, these soils often feel smooth and can hold a good amount of water. “Silt” and “Silt Loam” are examples.

- Clayey Soils: Rich in clay, these soils are often heavy, sticky when wet, and can hold a lot of water and nutrients, but may drain slowly. “Clay,” “Sandy Clay,” and “Silty Clay” fall into this category.

- Loamy Soils: Often considered ideal for agriculture, loams are a balanced mix of sand, silt, and clay, offering good drainage, water retention, and nutrient holding capacity. “Loam,” “Sandy Loam,” “Silt Loam,” and “Clay Loam” are common examples.

Why Does Soil Texture Matter? Practical Implications for Life

The textural class of soil has profound implications for almost every aspect of its function and how we interact with it. From gardening to engineering, understanding soil texture is paramount.

Water Holding Capacity and Drainage

This is perhaps the most immediate and noticeable impact of soil texture.

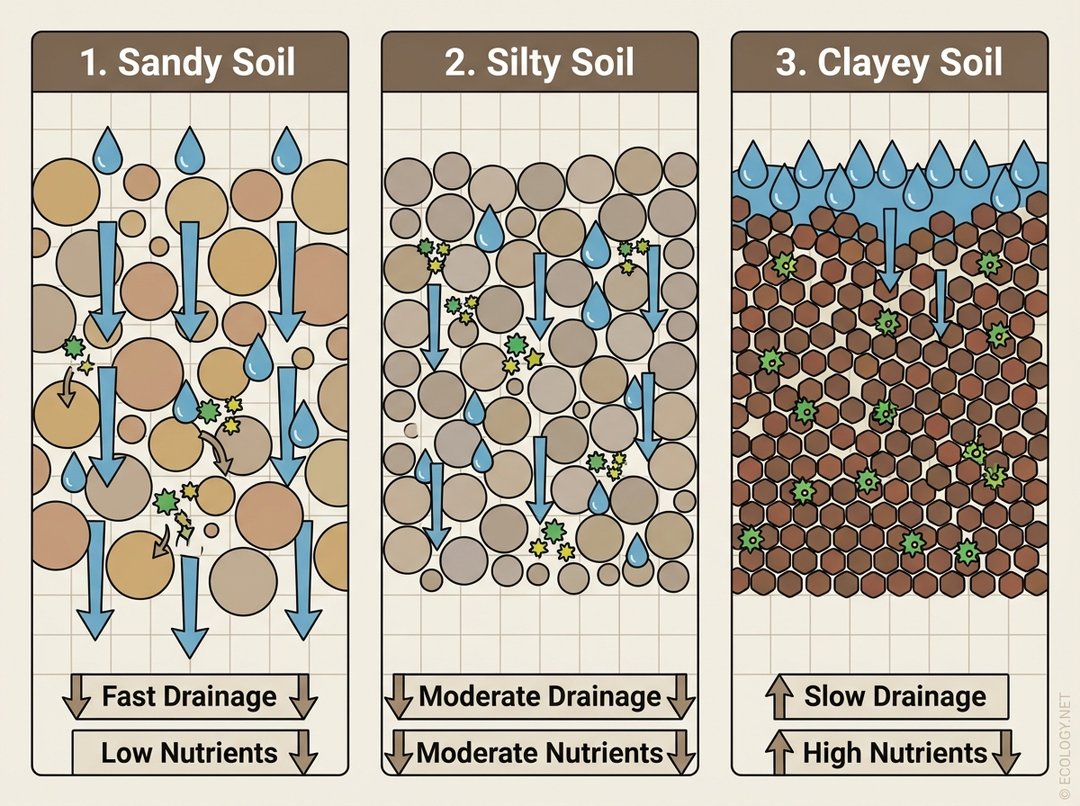

- Sandy soils, with their large pore spaces, drain very quickly. While this prevents waterlogging, it also means they dry out rapidly, requiring frequent irrigation for many plants.

- Clayey soils, conversely, have tiny, tightly packed pores. They hold a tremendous amount of water, often leading to slow drainage and potential waterlogging if not managed properly.

- Silty soils offer a middle ground, retaining moisture well but still allowing for adequate drainage.

- Loamy soils strike a desirable balance, providing good water retention without excessive waterlogging.

Nutrient Availability and Retention

Soil particles, particularly clay and organic matter, have electrical charges on their surfaces that can bind to essential plant nutrients.

- Clay particles, with their high surface area and negative charges, are excellent at holding onto positively charged nutrient ions (like calcium, magnesium, and potassium), preventing them from leaching away with water. This contributes to the fertility of clayey soils.

- Sandy soils have very little surface area and few charged sites, so nutrients tend to leach out quickly, making them less fertile unless regularly amended.

- Silty soils have moderate nutrient retention capabilities.

Aeration and Root Penetration

Plants need oxygen for their roots to respire, and roots need space to grow.

- Sandy soils are highly aerated due to large pore spaces, making it easy for roots to penetrate.

- Clayey soils can become very dense and compacted, especially when wet, limiting air circulation and making it difficult for roots to grow and spread.

- Loamy soils generally provide a good balance of aeration and ease of root penetration.

Workability and Tillage

The ease with which soil can be tilled or worked is also heavily influenced by texture.

- Sandy soils are often called “light” soils because they are easy to dig and cultivate.

- Clayey soils are “heavy” soils, becoming hard and cloddy when dry and sticky and unworkable when wet. Tilling clay at the wrong moisture content can lead to severe compaction.

- Silty soils are generally easy to work but can compact if repeatedly tilled when wet.

How to Determine Your Soil Texture

You do not need a laboratory to get a good idea of your soil’s texture. Simple field tests can provide valuable insights.

The Ribbon Test

- Take a small handful of moist soil (not soaking wet, not bone dry).

- Knead it thoroughly to break up any aggregates.

- Press the soil between your thumb and forefinger, pushing it out to form a ribbon.

- Observe how long the ribbon can be formed before it breaks:

- Sandy Soil: Forms no ribbon or a very short, crumbly one (less than 1 inch). Feels gritty.

- Silty Soil: Forms a short ribbon (1 to 2 inches) and feels smooth, like flour.

- Clayey Soil: Forms a long, strong ribbon (more than 2 inches) and feels sticky.

- Loamy Soil: Forms a moderate ribbon (1 to 2 inches) and feels somewhat gritty, somewhat smooth, and slightly sticky.

The Jar Test (Sedimentation Test)

- Fill a clear jar about one-third full with soil.

- Fill the rest of the jar with water, leaving some space at the top. Add a teaspoon of dish soap (this helps separate particles).

- Shake vigorously for several minutes until all soil aggregates are broken apart.

- Let the jar sit undisturbed.

- After 1 minute, the sand will have settled at the bottom. Mark its height.

- After 2 hours, the silt will have settled on top of the sand. Mark its height.

- After 24 hours (or even longer for very fine clay), the clay will have settled on top of the silt. Mark its height.

- Measure the height of each layer and the total height of the settled soil. Calculate the percentage of each component (e.g., (sand height / total height) * 100). You can then use the soil texture triangle to classify your soil.

Managing Soil Based on Texture

Knowing your soil’s texture empowers you to make informed decisions for gardening, landscaping, and land management.

- For Sandy Soils:

- Incorporate organic matter (compost, well-rotted manure) to improve water and nutrient retention.

- Consider drip irrigation to minimize water loss.

- Mulch heavily to conserve moisture.

- Fertilize more frequently with smaller doses.

- For Clayey Soils:

- Incorporate generous amounts of organic matter to improve drainage, aeration, and workability.

- Avoid working the soil when it is very wet, as this can lead to compaction.

- Consider raised beds to improve drainage.

- Choose plants that tolerate heavier soils.

- For Silty Soils:

- Maintain good organic matter levels to prevent compaction and crusting.

- Be mindful of erosion, as silt particles are easily carried away by wind and water.

- For Loamy Soils:

- These are often considered ideal. Focus on maintaining organic matter levels to preserve their excellent structure and fertility.

Conclusion

Soil texture is far more than a scientific classification; it is a fundamental characteristic that dictates the very lifeblood of our terrestrial ecosystems. From the microscopic interactions between water and mineral particles to the macroscopic health of forests and agricultural fields, texture plays a starring role. By understanding the simple yet profound differences between sand, silt, and clay, and by learning how to identify and manage the texture of the soil beneath our feet, we gain a deeper appreciation for the natural world and become better stewards of this invaluable resource.