Forests are more than just collections of trees; they are dynamic, complex ecosystems vital for life on Earth. They provide clean air and water, host incredible biodiversity, offer recreational spaces, and supply essential resources. However, without thoughtful intervention, these invaluable resources can be depleted or damaged. This is where the science and art of forest management come into play, a practice dedicated to balancing human needs with the long term health and vitality of forest ecosystems.

At its heart, forest management is the process of planning and implementing practices for the stewardship and use of forests and other associated land. It involves a holistic approach, considering ecological, economic, and social factors to ensure forests remain productive and resilient for generations to come. It is not simply about cutting down trees, but about understanding the intricate web of life within a forest and making informed decisions that benefit both nature and humanity.

The Foundational Principles Guiding Forest Management

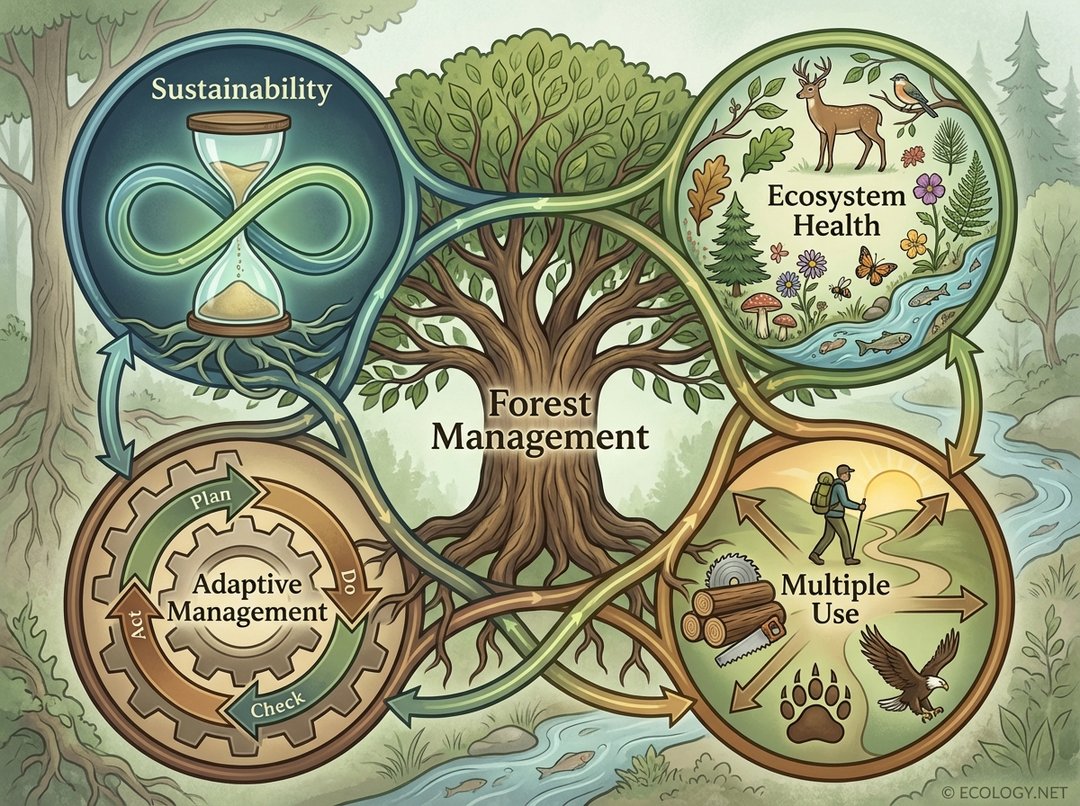

Effective forest management is built upon several core principles that guide decision making and ensure a balanced approach. These principles are interconnected, forming a framework for sustainable forest stewardship.

- Sustainability: This is perhaps the most crucial principle. Sustainable forest management means meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It involves harvesting timber at a rate that allows for natural regeneration, protecting soil and water resources, and maintaining the forest’s overall productive capacity.

- Ecosystem Health: A healthy forest is a resilient forest. This principle emphasizes maintaining or restoring the natural processes and biodiversity within a forest ecosystem. It involves protecting native species, managing invasive species, preventing widespread disease and pest outbreaks, and ensuring the integrity of forest habitats.

- Multiple Use: Forests provide a wide array of benefits beyond timber. The multiple use principle recognizes and strives to balance various forest uses, including timber production, wildlife habitat, recreation, water quality protection, and aesthetic values. For example, a single forest might be managed for sustainable logging, while also providing trails for hikers and critical habitat for endangered birds.

- Adaptive Management: Forests are constantly changing, influenced by natural processes, climate shifts, and human activities. Adaptive management is a flexible approach that involves continuously monitoring forest conditions, evaluating the effectiveness of management practices, and adjusting strategies as new information becomes available. It acknowledges uncertainty and promotes learning from experience.

Why Forest Management Matters: A Multifaceted Impact

The importance of sound forest management cannot be overstated. Its impacts ripple across environmental, economic, and social spheres.

Environmental Benefits

- Biodiversity Conservation: Well managed forests provide critical habitats for countless species of plants, animals, and microorganisms, helping to prevent species extinction and maintain ecological balance.

- Water Quality Protection: Forest canopies and root systems help regulate water cycles, reduce soil erosion, filter pollutants, and ensure a steady supply of clean water for communities.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Forests act as significant carbon sinks, absorbing vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Proper management enhances this sequestration capacity.

- Soil Health: Forest litter and root systems enrich soil, prevent erosion, and maintain soil structure, which is vital for nutrient cycling and overall ecosystem productivity.

Economic Contributions

- Timber and Wood Products: Forests provide renewable resources for construction, paper, furniture, and bioenergy, supporting industries and creating jobs.

- Non Timber Forest Products: Beyond wood, forests offer a wealth of other valuable products such as medicinal plants, wild foods, resins, and decorative materials.

- Recreation and Tourism: Forests attract visitors for hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, and wildlife viewing, boosting local economies through tourism.

Social and Cultural Values

- Recreational Opportunities: Forests offer spaces for relaxation, exercise, and connection with nature, contributing to human health and well being.

- Cultural and Spiritual Significance: Many indigenous communities and cultures hold deep spiritual and historical connections to forests, which are preserved through respectful management.

- Community Resilience: Healthy, well managed forests can protect communities from natural disasters like floods and landslides, and provide resources for local livelihoods.

Common Forest Harvesting Methods: A Closer Look

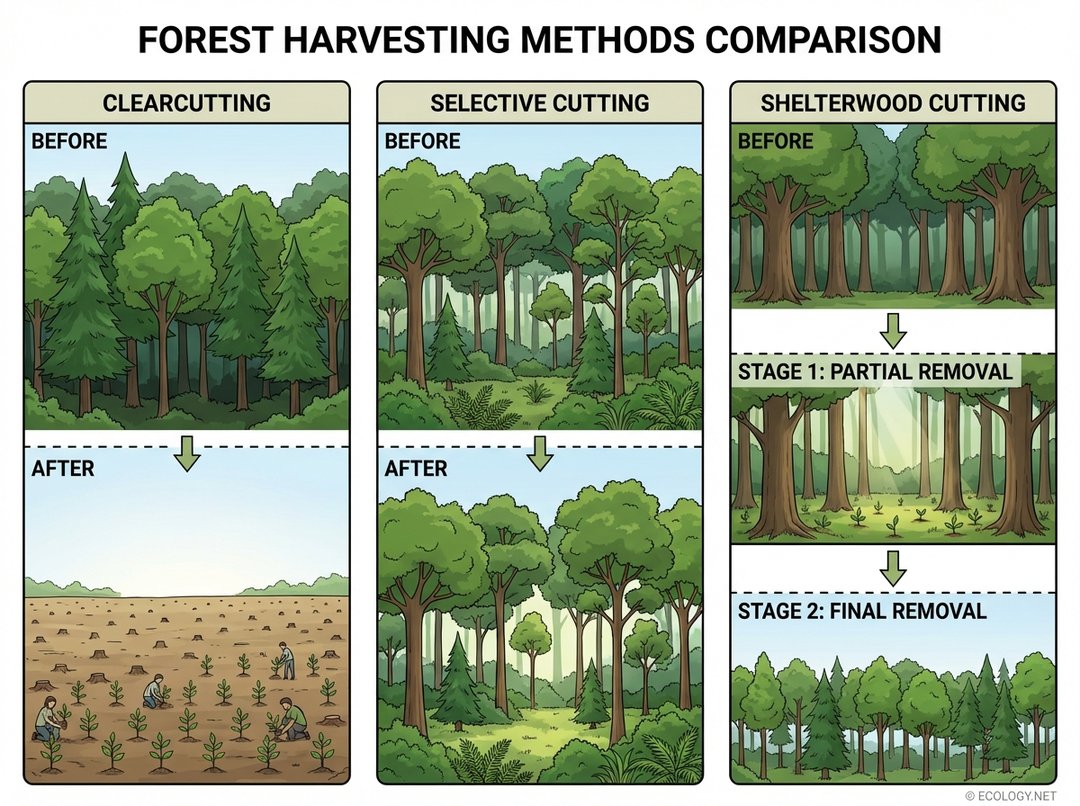

One of the most visible aspects of forest management is timber harvesting. Far from being a uniform process, various methods are employed, each with distinct ecological and economic outcomes. Understanding these methods is crucial for appreciating the nuances of sustainable forestry.

- Clearcutting: This method involves removing all trees from a designated area. While it can be controversial due to its dramatic visual impact, clearcutting can mimic natural disturbances like wildfires or insect outbreaks, promoting the regeneration of sun loving species. It is often used for species that require full sunlight to grow. After clearcutting, the area is typically replanted or allowed to regenerate naturally.

- Selective Cutting: In contrast to clearcutting, selective cutting involves removing only a portion of the trees in a stand, typically the mature, diseased, or poorly formed ones. This method aims to create an uneven aged forest structure, promoting continuous regeneration and maintaining a diverse canopy. It is less disruptive to the ecosystem and can preserve aesthetic values, but it is also more labor intensive.

- Shelterwood Cutting: This method is a two or three step process designed to create conditions for natural regeneration under the partial shade of existing trees.

- Initially, a portion of the mature trees is removed, creating an opening in the canopy that allows sunlight to reach the forest floor, encouraging new seedlings to grow.

- Once the new generation of trees is established, the remaining mature trees, which provided “shelter” for the young growth, are removed.

This method is particularly effective for species that thrive with some initial shade but eventually need more light to grow to maturity.

Advanced Concepts in Forest Management

Beyond the basic principles and harvesting techniques, modern forest management incorporates more sophisticated ecological understanding and addresses contemporary challenges.

Forests and Carbon Sequestration

One of the most critical roles forests play in the global ecosystem is their capacity for carbon sequestration. This is the process by which forests absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and store it in their biomass (trees, roots, leaves) and in the soil. This natural process is a powerful tool in mitigating climate change.

Forest management practices can significantly influence a forest’s carbon sequestration potential. For instance, maintaining healthy, growing forests, extending rotation lengths for timber harvesting, and promoting reforestation efforts all contribute to increased carbon storage. Conversely, deforestation and forest degradation release stored carbon back into the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change.

The careful management of forests is not just about timber or recreation; it is a fundamental strategy in the global effort to stabilize our climate. Every tree planted, every forest protected, contributes to a healthier planet.

Managing for Biodiversity

While timber production is a traditional focus, modern forest management places a strong emphasis on biodiversity conservation. This involves creating and maintaining diverse habitats, protecting old growth forests, managing for a variety of tree species and age classes, and ensuring connectivity between forest patches to allow wildlife movement. Strategies include:

- Retaining Snags and Downed Wood: Dead trees and logs provide crucial habitat for insects, fungi, birds, and small mammals.

- Protecting Riparian Zones: Areas along streams and rivers are vital for water quality and provide unique habitats.

- Creating Structural Diversity: Encouraging a mix of tree sizes, canopy layers, and understory vegetation supports a wider range of species.

Integrated Pest and Disease Management

Forests are susceptible to various pests and diseases, which can cause widespread damage and even mortality. Integrated pest management (IPM) in forestry involves a combination of strategies to prevent and control outbreaks, minimizing the need for chemical interventions. This includes:

- Monitoring: Regular surveys to detect early signs of pest or disease.

- Silvicultural Practices: Thinning, species selection, and promoting tree vigor to make forests more resistant.

- Biological Control: Using natural predators or pathogens to control pest populations.

- Targeted Treatments: Applying pesticides or fungicides only when necessary and in specific areas.

Challenges and the Future of Forest Management

Forest management faces numerous challenges in the 21st century, from the accelerating impacts of climate change to increasing demands for forest resources. Wildfires, prolonged droughts, and new invasive species pose significant threats, requiring innovative and adaptive solutions.

The future of forest management will likely involve an even greater emphasis on:

- Climate Smart Forestry: Practices that enhance a forest’s ability to adapt to climate change while also maximizing its carbon sequestration potential.

- Community Engagement: Greater involvement of local communities, indigenous peoples, and stakeholders in forest planning and decision making.

- Technological Advancements: Utilizing remote sensing, GIS, and data analytics for more precise monitoring, planning, and management.

- Restoration Ecology: Focusing on restoring degraded forest ecosystems to their natural health and function.

Conclusion

Forest management is a dynamic and essential discipline that bridges the gap between human needs and ecological imperatives. It is a continuous journey of learning, adapting, and striving for balance. By understanding and applying its core principles, from sustainable harvesting to carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation, humanity can ensure that forests continue to thrive, providing their invaluable benefits for all living things, now and far into the future. The health of our forests is inextricably linked to the health of our planet, making thoughtful forest stewardship a responsibility we all share.