Introduction: Unveiling the World of Grasslands

Imagine vast, open landscapes stretching to the horizon, teeming with life, where the wind whispers through endless fields of green and gold. These are grasslands, dynamic ecosystems that cover roughly one-quarter of the Earth’s land surface, playing a crucial role in global ecology and human civilization. Often overlooked in favor of more dramatic forests or deserts, grasslands are vibrant biomes with unique characteristics, incredible biodiversity, and profound ecological significance. From supporting iconic wildlife to influencing global climate, understanding grasslands is key to appreciating the intricate web of life on our planet.

What Defines a Grassland? The Rainfall Connection

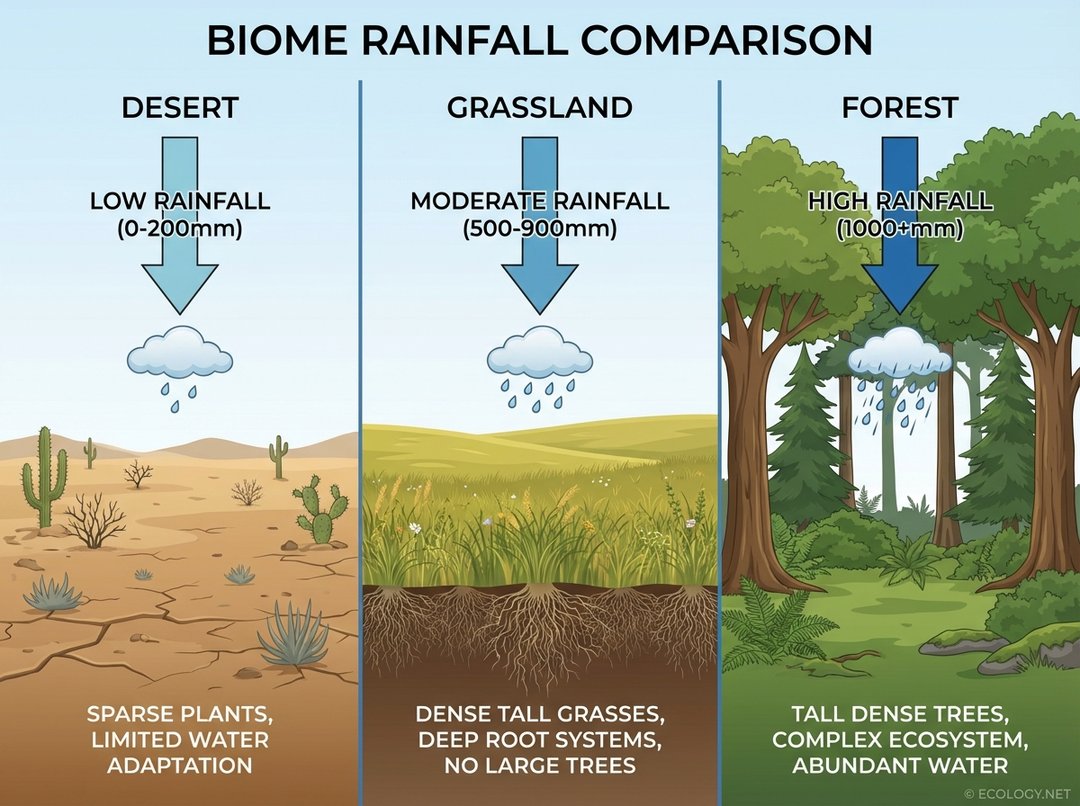

At its heart, a grassland is defined by its dominant vegetation: grasses. But what prevents these areas from becoming forests or deserts? The answer lies primarily in rainfall. Grasslands thrive in regions that receive too much rain for deserts to form, yet not enough to support the dense canopy of a forest. This delicate balance of precipitation, often coupled with factors like fire and grazing, shapes these unique environments.

Consider the spectrum of rainfall across different biomes:

- Deserts: Receive very low rainfall, typically less than 200mm annually, leading to sparse vegetation adapted to extreme aridity.

- Grasslands: Experience moderate rainfall, generally ranging from 500mm to 900mm per year. This amount is sufficient to support a continuous cover of grasses but insufficient for the growth of large, widespread trees.

- Forests: Characterized by high rainfall, often exceeding 1000mm annually, allowing for dense tree growth and complex forest structures.

This critical rainfall range dictates the types of plants that can flourish, making grasses the dominant life form in these expansive biomes. Their ability to grow quickly, reproduce efficiently, and withstand periods of drought or fire gives them a competitive edge in these moderate rainfall zones.

Types of Grasslands: A Global Perspective

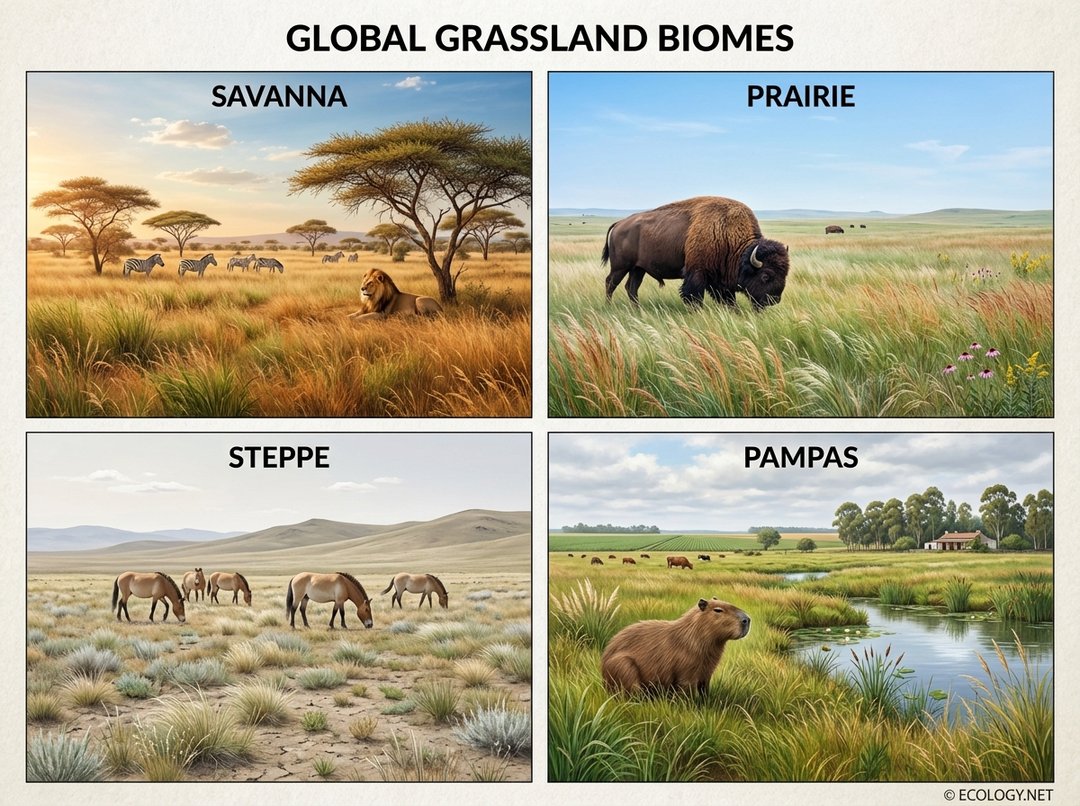

While all grasslands share the common trait of grass dominance, they are far from uniform. Variations in climate, geography, and evolutionary history have given rise to a diverse array of grassland types across the globe, each with its own distinct character and inhabitants. These major types are often categorized by their climate and typical vegetation structure.

Savannas: The Tropical Grasslands

Found in tropical and subtropical regions, savannas are characterized by tall grasses and scattered trees, often acacias or baobabs. They experience distinct wet and dry seasons. The iconic African savanna, for example, is home to an incredible diversity of large mammals, including lions, zebras, giraffes, and elephants, all adapted to its unique conditions. The presence of trees, though sparse, distinguishes savannas from other grassland types, often due to slightly higher rainfall or specific soil conditions that allow for some tree growth.

Prairies: The Temperate Grasslands of North America

Prairies are vast temperate grasslands primarily found in North America. Historically, they were dominated by tallgrass and shortgrass varieties, supporting immense herds of bison. Prairies experience hot summers and cold winters, with rainfall concentrated in the growing season. Their deep, fertile soils have made them incredibly productive agricultural lands, though much of the original prairie ecosystem has been converted for farming.

Steppes: The Dry, Open Grasslands of Eurasia

Steppes are temperate grasslands found across Eurasia, particularly in Central Asia. They are generally drier and experience more extreme temperature fluctuations than prairies, leading to shorter, sparser grasses. The Mongolian Steppe, for instance, is famous for its wild horses and nomadic cultures, reflecting an adaptation to its vast, open, and often harsh conditions. Steppes are characterized by their semi-arid climate and extensive, treeless plains.

Pampas: The Fertile Grasslands of South America

Located in South America, primarily Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil, the Pampas are fertile, temperate grasslands known for their lush, productive soils. They support a rich array of wildlife, including capybaras and various bird species, and are also significant agricultural regions, particularly for cattle ranching and crop cultivation. The Pampas generally receive more rainfall than steppes, contributing to their greater fertility and denser grass cover.

The Ecology of Grasslands: More Than Just Grass

Beyond their visual appeal and global distribution, grasslands are complex ecological systems driven by fascinating interactions between plants, animals, soil, and climate. Their resilience and productivity stem from several key adaptations and processes.

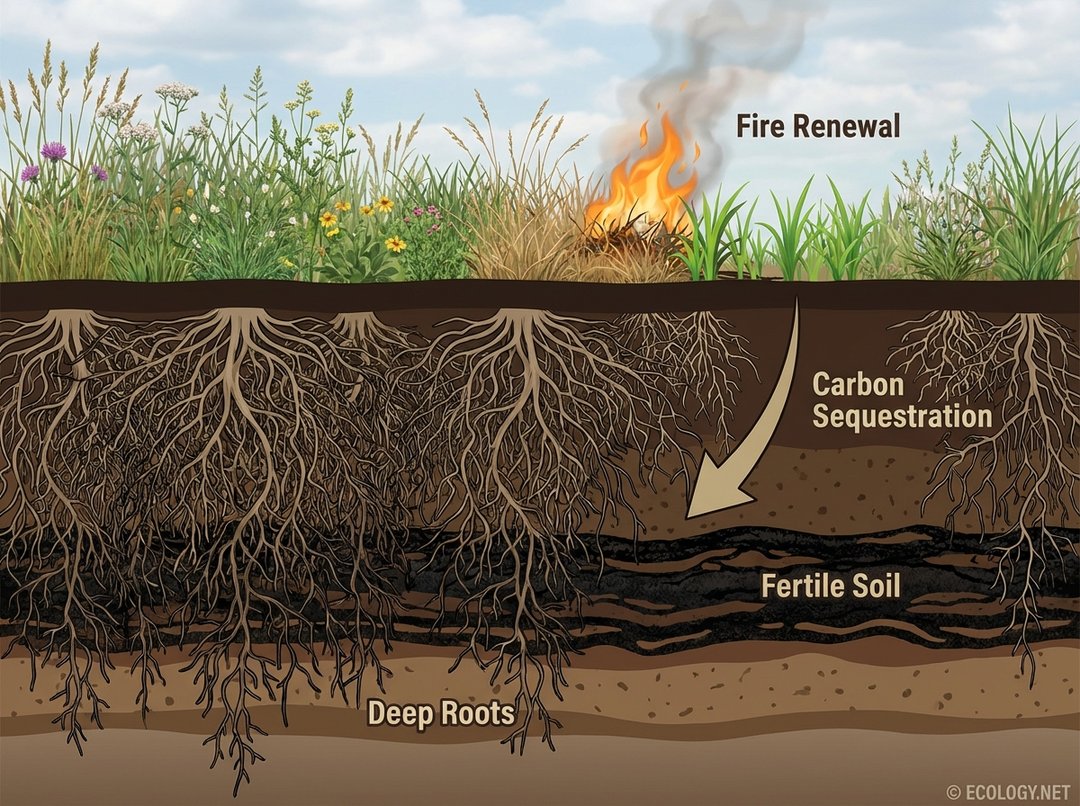

Deep Roots: The Hidden Strength

One of the most remarkable features of grassland plants, especially grasses, is their extensive and deep root systems. While the visible part of a grass plant might be relatively short, its roots can extend several feet into the soil. These deep roots serve multiple critical functions:

- Water Access: They allow grasses to tap into deeper water reserves during dry periods, making them highly resilient to drought.

- Nutrient Uptake: Deep roots efficiently absorb nutrients from various soil layers.

- Soil Stability: The dense network of roots binds the soil together, preventing erosion by wind and water.

- Regeneration: Many perennial grasses store energy in their root crowns, allowing them to quickly regrow after disturbances like fire or grazing.

Fire Renewal: A Natural Cycle

Fire is not merely a destructive force in grasslands; it is often a vital and natural component of the ecosystem. Many grasslands have evolved with regular fire regimes, which play a crucial role in maintaining their health and structure:

- Removes Woody Plants: Fires prevent the encroachment of trees and shrubs, which would otherwise outcompete grasses for light and water.

- Nutrient Cycling: Burning returns nutrients from dead plant material to the soil, enriching it for new growth.

- Stimulates Growth: Many grass species are fire-adapted, with their root systems protected underground. Fire clears old growth, allowing new, vigorous shoots to emerge.

- Pest Control: Fires can help control insect pests and plant diseases.

Controlled burns are often used in grassland management to mimic these natural processes and maintain ecosystem health.

Fertile Soil: The Foundation of Productivity

Grassland soils are renowned for their fertility, particularly the rich, dark topsoil known as chernozem. This fertility is a direct result of the continuous cycle of growth and decay of grass roots. As old roots die, they decompose, adding vast amounts of organic matter to the soil. This organic matter:

- Improves Soil Structure: Makes the soil crumbly and well-aerated.

- Increases Water Retention: Allows the soil to hold more moisture.

- Provides Nutrients: Releases essential nutrients for plant growth.

This deep, fertile soil is why many of the world’s most productive agricultural regions are found in former grasslands.

Carbon Sequestration: A Climate Ally

Grasslands are significant carbon sinks, playing a vital role in regulating the Earth’s climate. Through photosynthesis, grasses absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Instead of storing much of this carbon in woody stems above ground, as trees do, grasslands store a substantial amount in their extensive root systems and the rich organic matter of their soils. This process, known as carbon sequestration, makes grasslands crucial allies in mitigating climate change. The sheer volume of biomass below ground in a healthy grassland can store more carbon per acre than many forests.

Importance of Grasslands: Why Should We Care?

The ecological services provided by grasslands extend far beyond their aesthetic appeal. These biomes are indispensable for both natural systems and human well-being.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: Grasslands support a vast array of life, from iconic large mammals like bison and kangaroos to countless insects, birds, and reptiles. They are critical habitats for many endangered species.

- Agricultural Productivity: The fertile soils of grasslands are the foundation of much of the world’s food production, supporting extensive livestock grazing and crop cultivation, particularly grains like wheat, corn, and rice.

- Water Regulation: Grassland ecosystems help regulate water cycles by absorbing rainfall, reducing runoff, and recharging groundwater supplies. Their dense root systems prevent soil erosion, maintaining water quality.

- Climate Regulation: As significant carbon sinks, grasslands play a crucial role in mitigating climate change by storing vast amounts of carbon in their soils.

- Cultural Significance: Many human cultures have historically been shaped by grasslands, from nomadic pastoralists to agricultural societies, influencing traditions, economies, and ways of life.

Threats and Conservation: Protecting These Vital Biomes

Despite their immense value, grasslands are among the most threatened ecosystems on Earth. Major threats include:

- Habitat Loss and Conversion: The most significant threat is the conversion of grasslands to agricultural land, urban development, or other uses.

- Overgrazing: Unsustainable grazing practices can degrade grasslands, leading to soil erosion and a loss of biodiversity.

- Invasive Species: Non-native plants can outcompete native grasses, altering ecosystem structure and function.

- Altered Fire Regimes: Suppression of natural fires can lead to woody plant encroachment, while uncontrolled fires can be destructive.

- Climate Change: Changes in rainfall patterns and temperature can stress grassland ecosystems, leading to desertification or shifts in species composition.

Conservation efforts are crucial and often involve a multi-faceted approach:

- Sustainable Grazing: Implementing rotational grazing and other practices that mimic natural herbivore movements.

- Restoration: Replanting native grasses and restoring natural hydrological processes in degraded areas.

- Protected Areas: Establishing national parks and reserves to safeguard intact grassland ecosystems.

- Fire Management: Using prescribed burns to maintain ecosystem health and prevent uncontrolled wildfires.

- Policy and Education: Promoting policies that incentivize grassland conservation and educating the public about their importance.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Grasslands

Grasslands are far more than just fields of grass; they are dynamic, resilient, and profoundly important ecosystems that underpin much of life on Earth. From their defining rainfall patterns to their global diversity, from the hidden strength of their deep roots to their critical role in carbon sequestration, grasslands offer a compelling story of ecological ingenuity. As we face global challenges like climate change and biodiversity loss, recognizing and protecting these vital biomes becomes increasingly urgent. Their enduring legacy reminds us of the interconnectedness of nature and our responsibility to steward these magnificent landscapes for future generations.