In the grand tapestry of life on Earth, there are fundamental distinctions that dictate how organisms acquire the energy necessary to survive, grow, and reproduce. At the very foundation of nearly every ecosystem lies a remarkable group of organisms known as autotrophs. These are the unsung heroes, the primary producers, the architects of life as we know it.

Imagine a world where every living thing had to constantly hunt or forage for its food. It would be a chaotic, unsustainable existence. Thankfully, autotrophs provide the crucial service of converting raw, inorganic materials into organic compounds, essentially creating their own food. This incredible ability underpins the entire food web, making them indispensable for all other life forms.

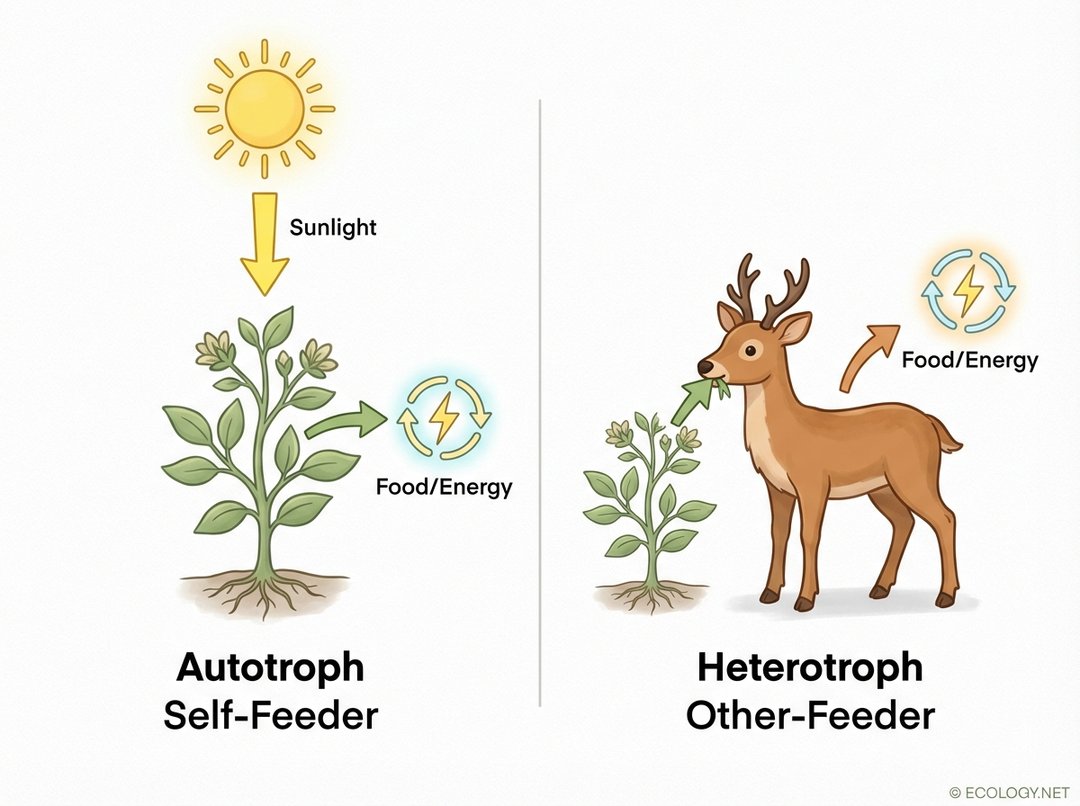

Autotrophs vs. Heterotrophs: The Fundamental Divide

To truly appreciate autotrophs, it is helpful to understand their counterparts: heterotrophs. The distinction is simple yet profound, defining how an organism obtains its energy.

- Autotrophs: From the Greek words “auto” (self) and “troph” (nourishment), autotrophs are “self-feeders.” They produce their own food using energy from non-living sources, such as sunlight or chemical reactions. They are the producers in an ecosystem.

- Heterotrophs: From the Greek “hetero” (other) and “troph” (nourishment), heterotrophs are “other-feeders.” They cannot produce their own food and must consume other organisms or organic matter to obtain energy. They are the consumers in an ecosystem.

Think of it this way: autotrophs are like the chefs who prepare the meals from scratch, using basic ingredients. Heterotrophs are the diners who come to the restaurant to eat the meals prepared by the chefs. Without the chefs, there would be no food for anyone else.

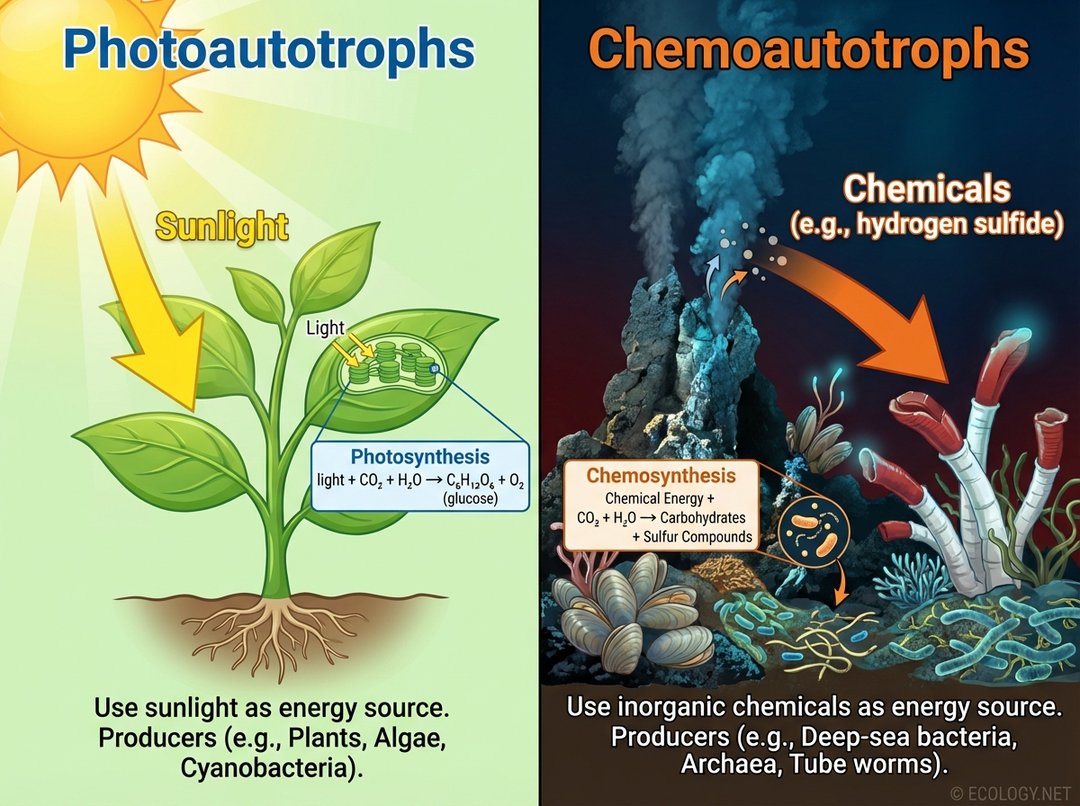

Two Main Types of Autotrophs: Harnessing Diverse Energy Sources

While the concept of “self-feeding” is consistent, autotrophs employ different strategies to capture and convert energy. These strategies lead to two primary classifications:

Photoautotrophs: The Sun’s Architects

The most widely recognized autotrophs are photoautotrophs. These organisms harness the power of sunlight to create their food through a process called photosynthesis. They are the green giants of our world, forming the base of nearly all terrestrial and most aquatic food webs.

- Energy Source: Sunlight

- Process: Photosynthesis

- Examples: Plants, algae, cyanobacteria (blue-green algae)

Chemoautotrophs: Life in the Dark

Less familiar, but equally vital, are chemoautotrophs. These remarkable organisms do not rely on sunlight. Instead, they derive energy from the oxidation of inorganic chemical compounds, a process known as chemosynthesis. They thrive in environments where sunlight cannot penetrate, such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents, volcanic springs, and even within the soil.

- Energy Source: Chemical reactions (e.g., hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, ferrous iron)

- Process: Chemosynthesis

- Examples: Certain bacteria and archaea found in extreme environments

The existence of chemoautotrophs dramatically expanded our understanding of where life can flourish, proving that sunlight is not the only prerequisite for primary production.

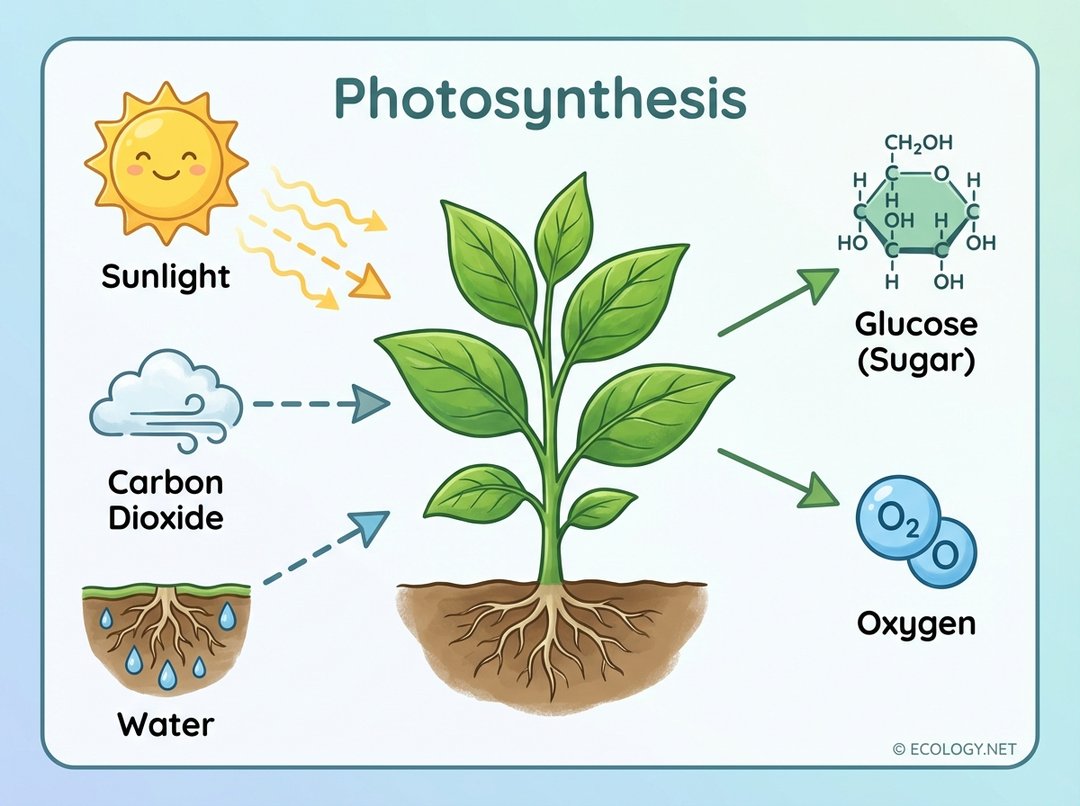

Photosynthesis in Detail: The Engine of Green Life

Since photoautotrophs are so prevalent, it is worth delving deeper into their primary energy-generating process: photosynthesis. This complex biochemical pathway is nothing short of miraculous, converting simple inorganic molecules into energy-rich sugars.

The word “photosynthesis” literally means “making with light.” It is the process by which green plants, algae, and some bacteria use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create glucose (a sugar, which is their food) and oxygen as a byproduct.

Here is a simplified breakdown of the inputs and outputs:

- Inputs:

- Sunlight: Provides the energy to drive the reaction.

- Carbon Dioxide (CO2): Absorbed from the atmosphere through tiny pores (stomata) on leaves.

- Water (H2O): Absorbed from the soil through roots.

- Outputs:

- Glucose (C6H12O6): A sugar molecule that serves as the plant’s primary energy source and building block.

- Oxygen (O2): Released into the atmosphere as a waste product, vital for the respiration of most living organisms.

This elegant process is carried out within specialized organelles called chloroplasts, which contain the green pigment chlorophyll. Chlorophyll is what gives plants their characteristic color and is essential for capturing light energy.

The Indispensable Role of Autotrophs in Ecosystems

Autotrophs are far more than just “self-feeders”; they are the bedrock of nearly every ecosystem on Earth. Their ecological importance cannot be overstated.

Producers at the Base of Food Webs

As primary producers, autotrophs are the first trophic level in almost all food chains. They convert inorganic energy into organic matter, making it available to heterotrophs. Without them, there would be no energy transfer to herbivores, and subsequently, no energy for carnivores or omnivores. Every bite of food any animal takes can ultimately be traced back to an autotroph.

Oxygen Production

Photoautotrophs, through photosynthesis, are responsible for producing the vast majority of the oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere. This oxygen is crucial for the aerobic respiration of most life forms, including humans. Forests, grasslands, and especially marine phytoplankton (microscopic algae) are constantly replenishing our planet’s oxygen supply.

Carbon Cycle Regulation

Autotrophs play a critical role in the global carbon cycle. They absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere during photosynthesis, converting it into organic compounds. This process helps to regulate Earth’s climate by sequestering carbon, preventing excessive buildup of greenhouse gases. When autotrophs die and decompose, or are consumed, carbon is transferred through the ecosystem.

Habitat Creation and Soil Formation

Beyond providing food and oxygen, autotrophs physically shape their environments. Plants create habitats for countless species, from the smallest insects to the largest mammals. Their roots stabilize soil, prevent erosion, and contribute to soil formation and nutrient cycling, creating fertile ground for future generations of life.

A World of Autotrophs: Diverse Examples

While plants are the most obvious examples, the autotrophic kingdom is incredibly diverse:

- Terrestrial Plants: From towering redwood trees to delicate mosses, all green plants are photoautotrophs. They dominate land ecosystems.

- Algae: A diverse group ranging from microscopic phytoplankton in oceans and freshwater to large seaweeds like kelp forests. Algae are crucial primary producers in aquatic environments.

- Cyanobacteria: Often called “blue-green algae,” these ancient bacteria were among the first organisms to perform oxygenic photosynthesis, fundamentally changing Earth’s atmosphere billions of years ago. They are still vital in many ecosystems.

- Chemosynthetic Bacteria and Archaea: These microscopic organisms thrive in extreme environments. Examples include sulfur-oxidizing bacteria near hydrothermal vents, nitrifying bacteria in soil, and iron-oxidizing bacteria.

Beyond the Basics: Autotrophic Adaptations and Extremes

The success of autotrophs lies in their incredible adaptability. They have evolved diverse strategies to thrive in nearly every corner of the planet.

- Light Adaptation: Some plants, like those in rainforest understories, have evolved large, thin leaves to capture scarce light. Others, like desert cacti, have reduced leaves and thick stems to minimize water loss while still photosynthesizing.

- Nutrient Acquisition: Autotrophs have developed intricate root systems to efficiently absorb water and minerals. Some, like carnivorous plants, even supplement their nutrient intake by trapping and digesting insects in nutrient-poor soils.

- Water Conservation: In arid environments, many autotrophs employ specialized photosynthetic pathways (like CAM photosynthesis) that allow them to open their stomata at night to absorb carbon dioxide, minimizing water loss during the hot day.

- Extreme Environments: Chemoautotrophs are the ultimate survivors, forming the base of ecosystems in places previously thought incapable of supporting life. Their ability to harness chemical energy allows them to flourish in the crushing pressures and toxic environments of deep-sea vents or the acidic waters of volcanic springs.

Conclusion: The Foundation of Life

Autotrophs are not just a category of organisms; they are the very foundation upon which almost all life on Earth is built. From the towering trees of a forest to the invisible bacteria at the bottom of the ocean, these self-feeding organisms tirelessly convert raw energy into the sustenance that fuels every other living thing. They produce the oxygen we breathe, regulate our climate, and create the habitats that shelter countless species.

Understanding autotrophs is key to understanding ecology, the flow of energy, and the interconnectedness of all life. They remind us of the incredible ingenuity of nature and the delicate balance that sustains our vibrant planet.