Unlocking Nature’s Schedule: The Wonders of Temporal Partitioning

Imagine a bustling city street. If everyone tried to use the same coffee shop, the same bus, and the same park bench at precisely the same moment, chaos would ensue. Resources would be stretched thin, and competition would be fierce. Nature, in its infinite wisdom, faces similar challenges, but it has devised an elegant solution to avoid constant gridlock: temporal partitioning. This fascinating ecological strategy allows diverse life forms to coexist by simply agreeing to take turns.

What is Temporal Partitioning?

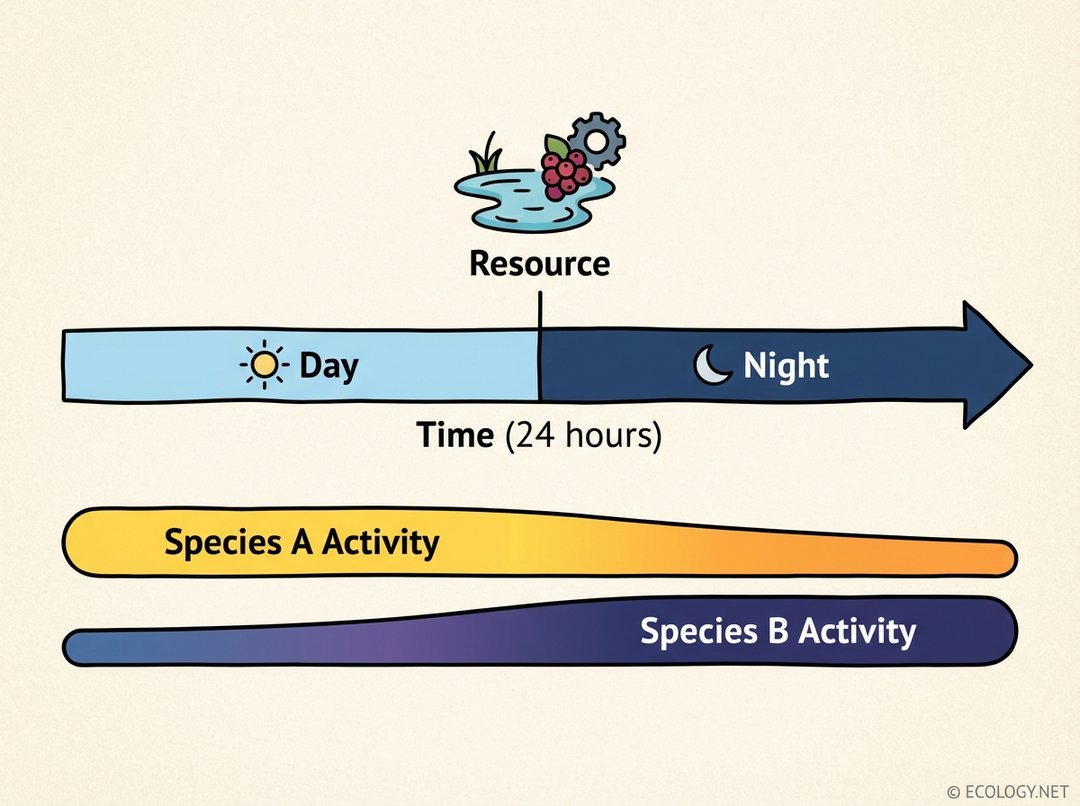

At its core, temporal partitioning is the division of time among different species to reduce direct competition for shared resources. Instead of fighting over a limited food source, a prime hunting ground, or even access to sunlight, species evolve to become active or utilize these resources at different times of the day, night, or even different seasons. It is nature’s way of scheduling, ensuring that everyone gets a turn without constant conflict.

This strategy is a fundamental aspect of how ecosystems maintain balance and support a rich diversity of life. By staggering their activities, species can effectively share a habitat, making the most of available resources without one species completely outcompeting another.

The Core Principle: Avoiding Direct Competition

The primary driver behind temporal partitioning is the reduction of interspecific competition. When two species require the same limited resource, such as food, water, or nesting sites, they can either compete directly, leading to one species dominating or even excluding the other, or they can find ways to coexist. Temporal partitioning offers a peaceful path to coexistence.

Consider a fruit tree in a forest. If all fruit-eating animals tried to feed from it simultaneously, the tree’s bounty would quickly diminish, and conflicts might arise. However, if some species feed during the day and others at night, the resource can sustain a greater number and variety of consumers over a longer period.

Real-World Examples of Temporal Partitioning

The natural world is teeming with examples of temporal partitioning, showcasing its versatility across various taxa and environments. From the smallest insects to the largest mammals, species have adapted their schedules to thrive.

Day and Night: Diurnal, Nocturnal, and Crepuscular Life

Perhaps the most intuitive example of temporal partitioning involves the division of activity between day and night.

- Diurnal Species: These are creatures active during daylight hours. Think of most songbirds, squirrels, butterflies, and many human activities. They utilize the sun’s energy, warmth, and visibility to forage, hunt, and interact.

- Nocturnal Species: These animals come alive after sunset. Owls, bats, raccoons, and many moths are classic examples. They exploit the cover of darkness to hunt prey that might be less active, avoid diurnal predators, or access resources that are only available or safer at night.

- Crepuscular Species: Some species prefer the twilight hours of dawn and dusk. Deer, rabbits, and many mosquitoes are crepuscular. These times often offer reduced visibility for predators, cooler temperatures than midday, and a transition period when both diurnal and nocturnal prey might be active.

A classic illustration is the hawk and the owl. Both are formidable predators of small rodents and birds, often inhabiting the same forest. However, hawks hunt by day, relying on keen eyesight in bright light, while owls hunt by night, using exceptional hearing and night vision. This temporal separation allows both apex predators to successfully exploit the same prey base without direct conflict.

Seasonal Shifts: A Calendar of Coexistence

Temporal partitioning extends beyond the 24-hour cycle to encompass seasonal changes.

- Migratory Birds: Many bird species migrate thousands of miles to exploit seasonal abundance of food and favorable breeding conditions. By moving to different geographical locations at different times of the year, they avoid competition with resident species and other migratory species that might follow a different schedule.

- Hibernation and Estivation: Animals that hibernate during winter or estivate during hot, dry summers are engaging in a form of temporal partitioning. They effectively “sit out” periods of resource scarcity, allowing other species to utilize the limited resources that remain active.

- Plant Flowering Times: Even plants exhibit temporal partitioning. Different species of wildflowers in the same meadow might bloom at slightly different times in spring and summer. This ensures that they attract different pollinators or reduce competition for pollinator services, maximizing their reproductive success. For example, early spring ephemerals bloom before the forest canopy leafs out, capturing sunlight that later-blooming plants cannot access.

Microbial Worlds: Invisible Schedules

Temporal partitioning is not limited to macroscopic life. In the microbial world, bacteria and fungi in a soil sample or a pond might utilize nutrients at different times, or under different light conditions, to avoid direct competition. This intricate scheduling contributes to the incredible biodiversity found even in seemingly simple environments.

Mechanisms and Factors Influencing Temporal Partitioning

The evolution of temporal partitioning is driven by a complex interplay of ecological pressures and physiological adaptations.

Environmental Cues

The most obvious cue is the light cycle, dictating day and night. However, other factors play a crucial role:

- Temperature: Some animals avoid the heat of midday, becoming active during cooler periods. Others might seek warmth during cooler parts of the day.

- Humidity: Many invertebrates are more active during periods of higher humidity, often at night, to prevent desiccation.

- Tides: Coastal organisms often synchronize their activities with tidal cycles, accessing resources exposed during low tide or feeding during high tide.

Predator Avoidance and Prey Availability

For many species, shifting their activity times is a strategy to avoid predators. A small mammal might be nocturnal to escape diurnal birds of prey. Conversely, predators might specialize in hunting at certain times to maximize their chances of encountering vulnerable prey. The availability of prey itself can dictate activity patterns; if a particular insect is only active at dusk, its predators might evolve to hunt at that time.

Physiological Adaptations

Species that engage in temporal partitioning often possess specific physiological adaptations:

- Sensory Organs: Nocturnal animals typically have highly developed night vision, acute hearing, or enhanced olfactory senses. Diurnal animals rely on excellent color vision and depth perception.

- Metabolism and Thermoregulation: Animals active at night or in cold seasons might have adaptations to maintain body temperature in cooler conditions.

- Internal Clocks: Circadian rhythms, the internal biological clocks, regulate daily cycles of activity, feeding, and sleep, ensuring species adhere to their specific temporal niche.

Advanced Concepts: Temporal Partitioning within Niche Differentiation

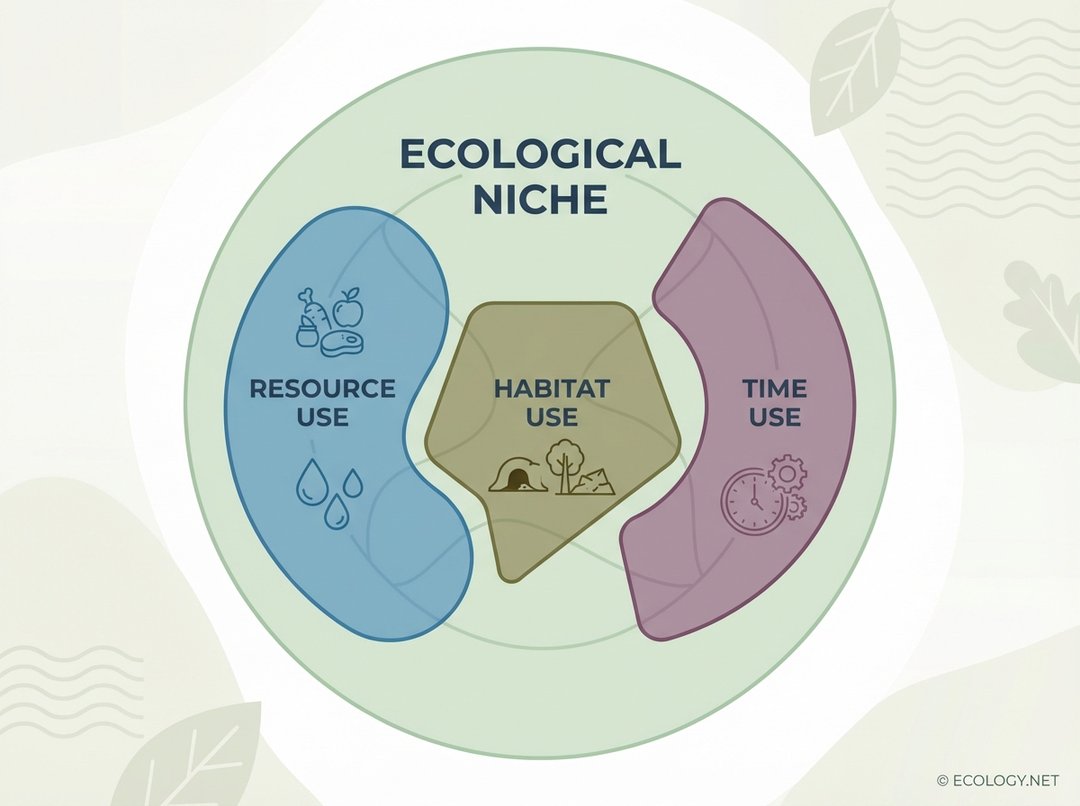

Temporal partitioning is not an isolated phenomenon but rather a critical component of a broader ecological concept known as niche differentiation. An ecological niche describes the role and position a species has in its environment, encompassing all its interactions with the biotic and abiotic factors of its habitat.

Niche differentiation occurs when competing species evolve to use different resources, habitats, or times, thereby minimizing overlap in their ecological requirements. This allows multiple species to coexist in the same general area. Temporal partitioning is one of the three primary axes along which niche differentiation can occur:

- Resource Partitioning: Species use different types of resources or different parts of the same resource. For example, different bird species might feed on different sizes of seeds from the same plant.

- Spatial Partitioning: Species use different physical locations or habitats. For instance, different warbler species might forage in different parts of the same tree canopy.

- Temporal Partitioning: Species use the same resources or habitats but at different times, as we have explored.

Often, species employ a combination of these strategies. For example, two species might be primarily nocturnal (temporal partitioning) but also forage in different parts of the forest (spatial partitioning) and consume slightly different types of insects (resource partitioning). This multi-faceted approach to niche differentiation is what allows for the incredible biodiversity observed in healthy ecosystems.

The Enduring Importance of Nature’s Schedule

Temporal partitioning is a testament to the intricate and often subtle ways in which life on Earth adapts to coexist. It highlights that competition is not always a battle to the death but can often lead to elegant solutions that promote biodiversity and ecosystem stability. By understanding how species divide their time, ecologists gain crucial insights into community structure, species interactions, and the resilience of natural systems. As environments change, understanding these fundamental ecological principles becomes ever more vital for conservation efforts and for appreciating the profound wisdom embedded in nature’s schedule.