Forests are often seen as monolithic green expanses, vital for life on Earth. However, a closer look reveals a spectrum of health and vitality within these crucial ecosystems. While the complete removal of forests, known as deforestation, rightly garners significant attention, a more insidious and widespread threat often operates under the radar: forest degradation. Understanding this nuanced concept is paramount to effective conservation and the sustainable future of our planet.

Distinguishing Degradation from Deforestation

To truly grasp the challenge of forest degradation, it is essential to first differentiate it from its more dramatic counterpart, deforestation. Both involve the loss of forest cover, but they differ fundamentally in their extent and nature.

Deforestation refers to the complete removal of forest land for other uses, such as agriculture, urban development, or mining. It results in a permanent or long-term conversion of forest to non-forest land. The trees are gone, and the land is transformed.

Forest degradation, on the other hand, is a more subtle process. It involves a reduction in the quality, structure, and ecological function of a forest, without necessarily a complete loss of tree cover. The forest is still there, but it is less healthy, less diverse, and less capable of providing its full range of ecosystem services. It is a decline in the forest’s overall integrity and resilience.

Imagine a healthy, vibrant forest as a thriving city. Deforestation is like bulldozing that city to build a factory. Forest degradation is like letting the city’s infrastructure crumble, its services decline, and its population dwindle, even while the buildings still stand.

The Many Faces of Forest Degradation

Forest degradation is not a single event but a complex process driven by a variety of human activities and natural disturbances, often exacerbated by climate change. Its manifestations are diverse, reflecting the specific pressures exerted on different forest types around the world.

Unsustainable Logging Practices

One of the most significant drivers of degradation is unsustainable logging. While selective logging, the removal of only certain tree species or sizes, can be managed sustainably, often it is not. Poorly planned logging operations can lead to:

- High-grading: The removal of the largest and most valuable trees, leaving behind a forest composed of smaller, less commercially valuable, or less resilient species. This depletes the genetic stock and alters forest composition.

- Collateral damage: Heavy machinery used for logging can compact soil, damage remaining trees, and create extensive road networks that fragment habitats and open forests to further exploitation.

- Reduced canopy cover: Even if not all trees are removed, significant gaps in the canopy can alter microclimates, increase light penetration, and change understory vegetation, impacting species that rely on shade and stable conditions.

Fuelwood Collection and Charcoal Production

In many parts of the world, particularly in developing countries, forests are a primary source of energy. The unsustainable collection of fuelwood and the production of charcoal can lead to localized but severe degradation, especially around human settlements. This often involves the removal of young trees and branches, preventing forest regeneration and reducing overall biomass.

Overgrazing

When livestock graze excessively within forest areas, they can prevent the regeneration of tree seedlings, compact soil, and alter understory vegetation. This can lead to a more open, less diverse forest structure, making it more susceptible to erosion and invasive species.

Forest Fires

While some ecosystems are adapted to natural fire regimes, human-induced fires, often linked to agricultural expansion or arson, can be devastating. Even fires that do not completely destroy a forest can degrade it by killing mature trees, altering species composition, and reducing soil fertility. Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of these fires, pushing many forests beyond their natural resilience.

Pests and Diseases

Forests naturally experience outbreaks of pests and diseases. However, degraded forests, often stressed by other factors like drought or pollution, can become more vulnerable to widespread infestations. These outbreaks can lead to significant tree mortality, altering forest structure and function over large areas.

Pollution and Climate Change

Atmospheric pollution, such as acid rain, can directly harm trees and soil health, leading to reduced growth and increased vulnerability to other stressors. Climate change itself is a major driver of degradation, causing shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns, increasing the frequency of extreme weather events, and pushing forest ecosystems beyond their adaptive capacity.

The Consequences of a Declining Forest

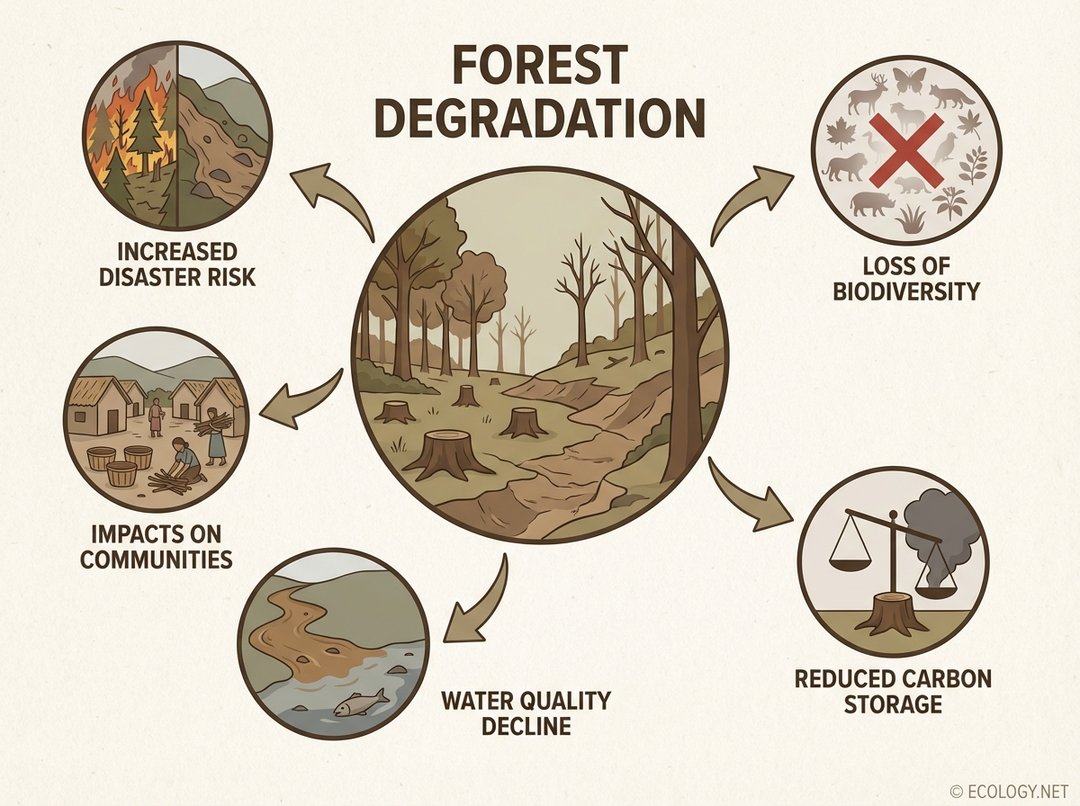

The impacts of forest degradation are far-reaching, affecting not only the immediate ecosystem but also global climate, biodiversity, and human well-being. These consequences often cascade, creating a vicious cycle of decline.

Loss of Biodiversity

Degraded forests lose their structural complexity and species diversity. The removal of specific tree species, the alteration of canopy cover, and the disturbance of undergrowth can eliminate habitats for countless plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms. This reduction in biodiversity weakens the entire ecosystem, making it less resilient to future disturbances.

Reduced Carbon Storage

Healthy forests are massive carbon sinks, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in their biomass and soils. Degradation reduces the forest’s capacity to store carbon. When large, old trees are removed, or when forest health declines, less carbon is sequestered, and stored carbon can be released back into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

Water Quality Decline and Hydrological Impacts

Forests play a critical role in regulating water cycles. Their canopies intercept rainfall, their roots stabilize soil, and their leaf litter helps water infiltrate the ground. Degraded forests lose these functions, leading to:

- Increased surface runoff and erosion, which can lead to soil loss.

- Sedimentation of rivers and streams, reducing water quality and harming aquatic life.

- Reduced groundwater recharge, impacting water availability for downstream communities.

- Increased risk of floods and droughts.

Impacts on Communities and Livelihoods

Millions of people worldwide depend directly on forests for their livelihoods, including food, medicine, building materials, and cultural resources. Degradation diminishes these vital resources, leading to food insecurity, loss of traditional knowledge, and economic hardship for forest-dependent communities. It can also exacerbate social conflicts over dwindling resources.

Increased Disaster Risk

Healthy forests act as natural buffers against many environmental hazards. Degraded forests, however, offer less protection. They are more vulnerable to:

- Wildfires: Drier, less healthy forests with altered fuel loads can burn more frequently and intensely.

- Landslides and soil erosion: With less root structure to hold soil in place, degraded slopes are more prone to collapse, especially during heavy rainfall.

- Flooding: Reduced water absorption capacity increases the risk and severity of floods.

Addressing Forest Degradation: A Path Forward

Combating forest degradation requires a multi-faceted approach that goes beyond simply preventing deforestation. It demands a shift towards sustainable forest management, restoration, and a deeper appreciation for the ecological integrity of these vital ecosystems.

Sustainable Forest Management

This involves managing forests in a way that maintains their biodiversity, productivity, regeneration capacity, vitality, and their potential to fulfill, now and in the future, relevant ecological, economic, and social functions, at local, national, and global levels, and that does not cause damage to other ecosystems. Key aspects include:

- Careful planning of logging operations to minimize impact.

- Protecting critical habitats and biodiversity hotspots.

- Promoting natural regeneration and reforestation.

- Developing non-timber forest product industries to reduce pressure on timber.

Forest Restoration

For already degraded areas, active restoration efforts are crucial. This can range from assisted natural regeneration, where human intervention helps natural processes, to active tree planting and ecological engineering to restore forest structure and function. Restoration aims to bring the forest back to a state where it can once again provide its full range of ecosystem services.

Policy and Governance

Strong policies and effective governance are essential to prevent and reverse degradation. This includes:

- Enforcing laws against illegal logging and land conversion.

- Establishing protected areas and conservation zones.

- Providing incentives for sustainable practices.

- Addressing underlying drivers of degradation, such as poverty and insecure land tenure.

Community Involvement

Engaging local and indigenous communities, who often possess invaluable traditional knowledge about forest management, is critical. Empowering communities to manage their forests sustainably can lead to more effective and equitable conservation outcomes.

Conclusion

Forest degradation is a silent crisis, often overshadowed by the more visible act of deforestation. Yet, its cumulative impact on biodiversity, climate stability, water resources, and human livelihoods is profound. Recognizing the subtle signs of a declining forest and understanding the complex interplay of its causes and consequences is the first step towards safeguarding these irreplaceable ecosystems. By embracing sustainable practices, investing in restoration, and fostering a global commitment to forest health, humanity can work towards a future where forests not only endure but thrive, continuing to provide their life-sustaining benefits for generations to come.