Often overlooked or simply admired for their fleeting beauty, fungi represent an entire kingdom of life that is as mysterious as it is vital. Far more than just the mushrooms that sprout after a rain, fungi are the silent architects of ecosystems, the hidden engineers of nutrient cycles, and even the unsung heroes of medicine and cuisine. Delving into the world of fungi reveals an intricate web of life that underpins nearly every terrestrial environment on Earth.

The Hidden World Beneath Our Feet: Structure and Function

To truly appreciate fungi, one must first understand their fundamental structure and how they interact with their environment. Unlike plants, fungi do not photosynthesize. Unlike animals, they do not ingest their food internally. Instead, fungi have developed a unique and highly efficient method of nutrient acquisition.

The Anatomy of a Fungus: More Than Just a Mushroom

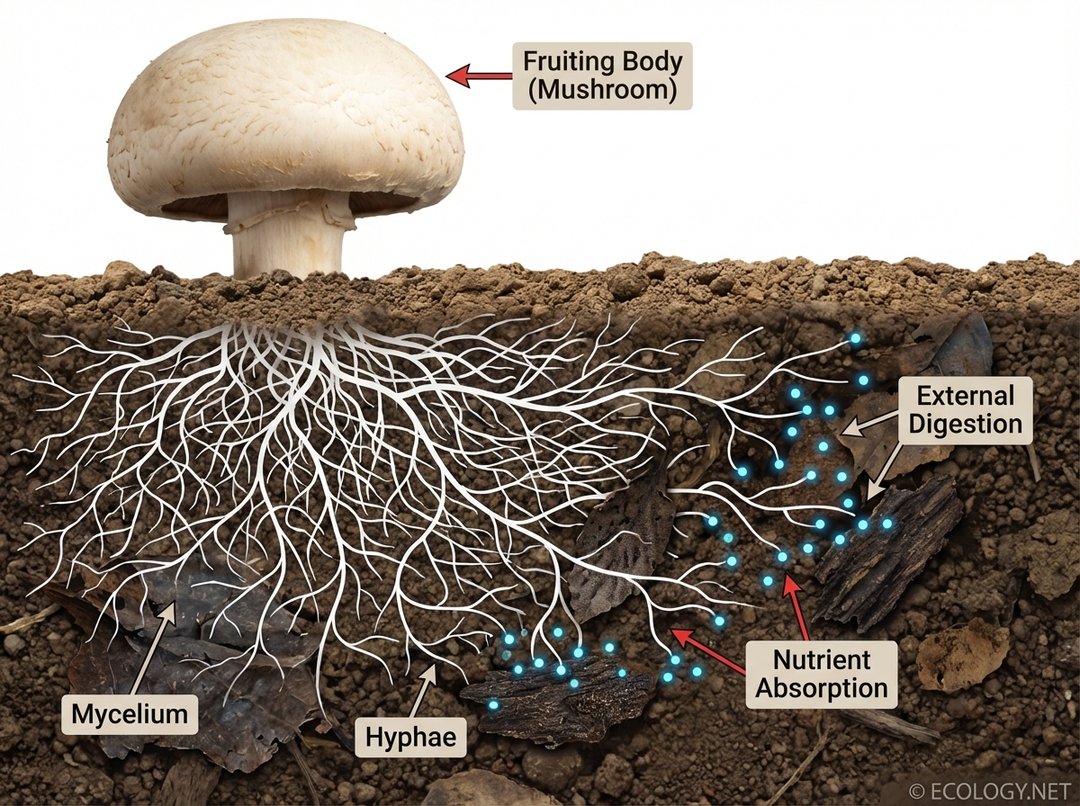

When most people think of a fungus, they picture a mushroom. However, the mushroom, known scientifically as the fruiting body, is merely the reproductive structure of a much larger organism. The true body of a fungus lies mostly hidden beneath the soil or within its food source.

- Mycelium: This is the vegetative part of a fungus, consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like structures called hyphae. The mycelium can spread for vast distances, sometimes covering acres, making it one of the largest organisms on Earth.

- Hyphae: These are individual microscopic filaments that make up the mycelium. Hyphae are the primary means by which fungi grow and absorb nutrients. They are incredibly efficient at penetrating substrates, allowing fungi to access resources unavailable to other organisms.

- Fruiting Body (Mushroom): The visible part of many fungi, responsible for producing and dispersing spores for reproduction. Its form varies wildly, from the familiar cap and stalk of a toadstool to the intricate folds of a morel.

How Fungi “Eat”: External Digestion and Absorption

Fungi are heterotrophs, meaning they obtain their nutrients from external sources. Their feeding strategy is truly remarkable and sets them apart from plants and animals. Instead of consuming food and digesting it internally, fungi perform external digestion.

- Secretion of Enzymes: Fungal hyphae release powerful digestive enzymes directly into their surroundings. These enzymes break down complex organic molecules in the environment, such as cellulose, lignin, and proteins, into smaller, soluble compounds.

- Nutrient Absorption: Once the complex molecules are broken down, the hyphae absorb these simpler nutrients directly through their cell walls. This highly efficient absorption process allows fungi to thrive on a wide range of organic materials, from dead wood and leaves to animal remains and even petroleum products.

This method of feeding makes fungi indispensable decomposers in nearly every ecosystem, recycling vital nutrients back into the soil for other organisms to use.

Fungi’s Ecological Superpowers: Decomposers, Symbionts, and More

The ecological roles of fungi are incredibly diverse and profoundly impact the health and functioning of ecosystems worldwide. They are not just passive inhabitants but active participants in the grand cycles of nature.

The Ultimate Recyclers: Decomposers

Perhaps the most critical role of fungi is that of decomposers. Without them, forests would be choked with fallen trees and dead leaves, and essential nutrients would remain locked away in organic matter. Fungi, alongside bacteria, are the primary agents responsible for breaking down dead organic material, returning carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus to the soil and atmosphere. This nutrient cycling is fundamental for sustaining plant growth and, by extension, all life on Earth.

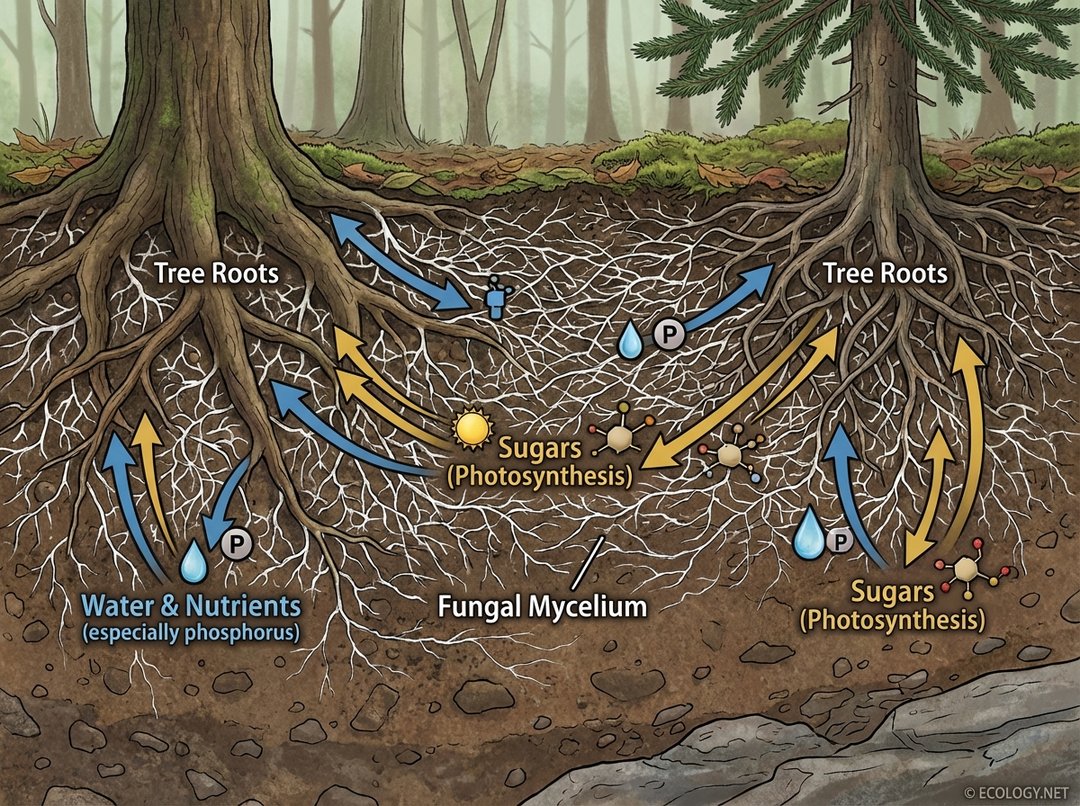

The “Wood Wide Web”: Mycorrhizal Networks

Beyond decomposition, many fungi form intricate and mutually beneficial relationships with other organisms. One of the most significant examples is mycorrhizae, a symbiotic association between fungi and plant roots. The term “mycorrhiza” literally means “fungus root.”

In these partnerships:

- Fungi Benefit: Plants, through photosynthesis, produce sugars. Fungi, unable to photosynthesize, receive a steady supply of these vital carbohydrates from their plant partners.

- Plants Benefit: The fungal hyphae extend far beyond the reach of the plant’s own roots, effectively increasing the plant’s root surface area by hundreds or even thousands of times. This allows the plant to absorb water and crucial nutrients, especially phosphorus and nitrogen, much more efficiently from the soil.

These mycorrhizal networks are so extensive and interconnected that they are often referred to as the “wood wide web,” facilitating communication and nutrient exchange between different plants in a forest. A single tree might be connected to dozens of other trees, even those of different species, through this subterranean fungal network.

Other Symbiotic Relationships

- Lichens: These fascinating organisms are a symbiotic partnership between a fungus and an alga or cyanobacterium. The fungus provides a protective structure and absorbs water and minerals, while the alga or cyanobacterium performs photosynthesis, providing food for both partners. Lichens are pioneer species, capable of colonizing harsh environments like bare rock.

- Endophytes: Some fungi live within plant tissues without causing disease, often providing benefits such as increased drought resistance or protection against herbivores.

Fungi as Parasites and Pathogens

While many fungi are beneficial, some can be parasitic, causing diseases in plants, animals, and even humans. Examples include:

- Plant Diseases: Rusts, smuts, mildews, and blights are common fungal diseases that can devastate crops and natural ecosystems.

- Animal and Human Infections: Fungi can cause a range of infections, from superficial skin conditions like athlete’s foot and ringworm to more serious systemic infections, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems.

Beyond the Mushroom: The Incredible Diversity of Fungi

The fungal kingdom is astonishingly diverse, encompassing an estimated 2.2 to 3.8 million species, only a fraction of which have been formally described. This vast array of life forms includes much more than just the familiar mushroom.

Major Fungal Groups

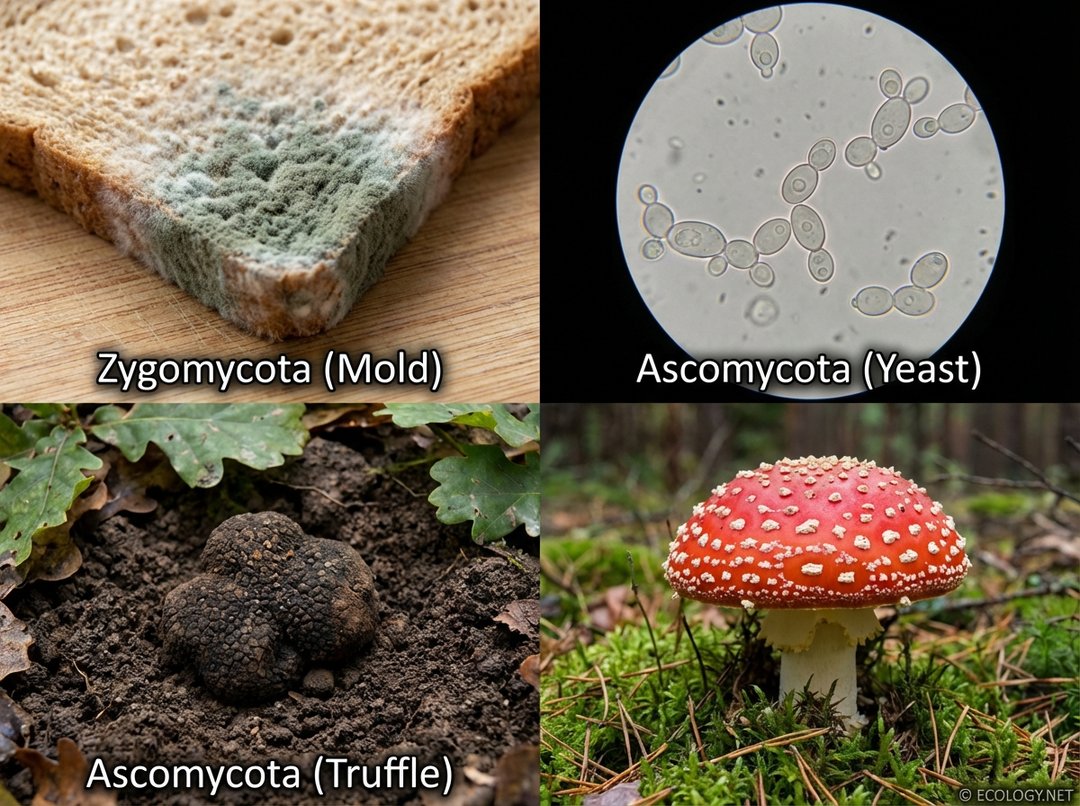

Scientists classify fungi into several major phyla, each with distinct characteristics:

- Zygomycota (Molds): This group includes many common molds, such as the fuzzy grey-green bread mold (Rhizopus stolonifer). They are characterized by their rapidly growing mycelia and the production of zygospores during sexual reproduction.

- Ascomycota (Sac Fungi): This is the largest phylum of fungi, incredibly diverse, and includes yeasts, morels, truffles, cup fungi, and many plant pathogens. They are defined by their sac-like reproductive structure called an ascus, which contains spores.

- Yeasts: Single-celled fungi, famous for their role in fermentation (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae in baking and brewing).

- Truffles: Highly prized edible fungi that grow underground in symbiotic association with tree roots.

- Basidiomycota (Club Fungi): This phylum includes most of the fungi commonly recognized as mushrooms, toadstools, puffballs, bracket fungi, and rusts. They are characterized by their club-shaped reproductive structure called a basidium, which produces spores.

Fungi in Human Society: From Food to Medicine

The impact of fungi on human civilization is immense, extending far beyond their ecological roles. They are integral to our food systems, medicine, and even industrial processes.

Culinary Delights

- Mushrooms: Many species are highly valued for their culinary properties, offering unique flavors and textures. Examples include shiitake, oyster, portobello, and the elusive truffle.

- Yeast: Essential for baking bread, where it ferments sugars to produce carbon dioxide, causing the dough to rise. It is also crucial in the production of alcoholic beverages like beer and wine.

- Cheese Production: Certain fungi are used to ripen and flavor cheeses, such as the blue veins in Roquefort or the white rind on Brie.

Medicinal Marvels

The discovery of penicillin from the fungus Penicillium chrysogenum by Alexander Fleming revolutionized medicine, ushering in the age of antibiotics. This single discovery has saved countless lives. Beyond antibiotics, fungi are sources of other important pharmaceuticals:

- Immunosuppressants: Cyclosporine, derived from a fungus, is vital for preventing organ rejection in transplant patients.

- Statins: Some cholesterol-lowering drugs, like lovastatin, were originally isolated from fungi.

Bioremediation and Biotechnology

Fungi’s powerful digestive enzymes make them valuable tools in bioremediation, the process of using biological organisms to clean up environmental pollutants. They can break down complex toxins, including pesticides, plastics, and even crude oil. In biotechnology, fungi are used to produce enzymes for industrial processes, biofuels, and various organic acids.

Conclusion: The Indispensable Kingdom

From the microscopic yeast cell to the vast underground mycelial networks, fungi are an indispensable part of life on Earth. They are the great recyclers, the silent partners in plant growth, and a source of both sustenance and healing for humanity. Understanding fungi is not just an academic exercise; it is key to comprehending the intricate balance of our planet’s ecosystems and harnessing their potential for a sustainable future. The more we learn about this fascinating kingdom, the more we appreciate its profound and often hidden influence on the world around us.