The natural world, in all its breathtaking complexity, often appears as a collection of individual organisms living their separate lives. Yet, beneath this apparent independence lies an intricate, pulsating network of relationships, a grand tapestry woven from the fundamental need for energy. This tapestry is what ecologists call a food web, a concept far more dynamic and revealing than the simple food chain often taught in school.

Understanding food webs is not merely an academic exercise; it is a vital lens through which to view the health and resilience of every ecosystem on Earth, from the smallest pond to the vastest ocean. It reveals how the disappearance of one species can ripple through an entire community, how pollution can climb the biological ladder, and why conserving biodiversity is paramount for the stability of our planet.

The Foundation of Life: What is a Food Web?

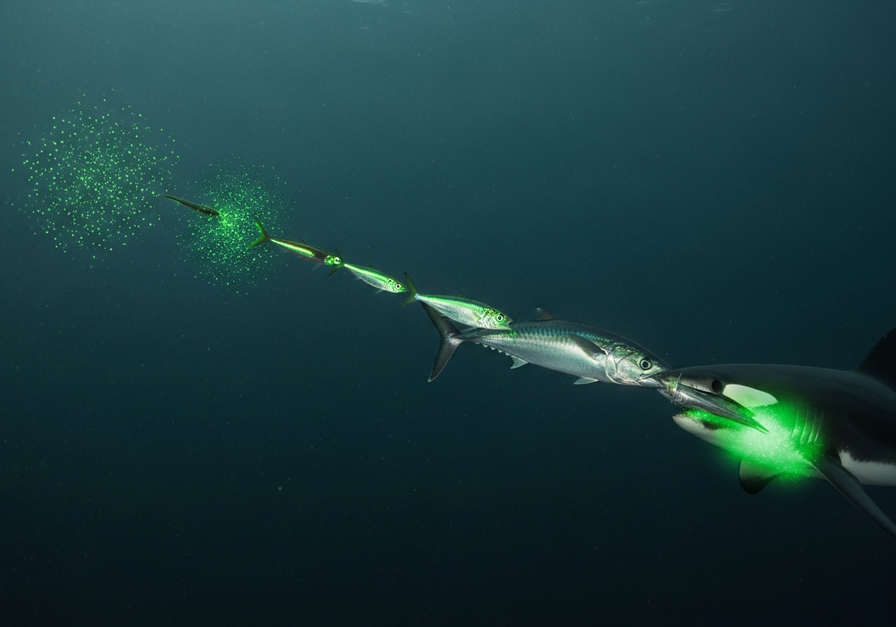

At its core, a food web illustrates who eats whom within an ecological community. It is a diagram showing the flow of energy and nutrients from one organism to another. Unlike a linear food chain, which depicts a single pathway, a food web is a complex, interconnected network of multiple food chains, reflecting the reality that most organisms have varied diets and are preyed upon by multiple predators.

Consider a forest. A deer eats various plants, but those plants are also eaten by insects, squirrels, and birds. The deer might be hunted by a wolf, but the wolf also preys on elk and moose. The insects are eaten by birds, which are then eaten by hawks. This intricate web of consumption is what defines a food web.

The Essential Players: Trophic Levels

Every organism within a food web occupies a specific trophic level, a position in the food chain determined by its primary source of energy. These levels are fundamental to understanding energy transfer.

- Producers (Autotrophs): These are the base of almost every food web. Producers create their own food, typically through photosynthesis, converting sunlight into chemical energy.

- Examples: Plants, algae, phytoplankton.

- Consumers (Heterotrophs): Organisms that obtain energy by consuming other organisms. Consumers are further categorized by what they eat:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Eat producers.

- Examples: Deer, rabbits, caterpillars, zooplankton.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): Eat primary consumers.

- Examples: Foxes eating rabbits, small birds eating insects, fish eating zooplankton.

- Tertiary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): Eat secondary consumers.

- Examples: Hawks eating small birds, wolves eating foxes, larger fish eating smaller fish.

- Quaternary Consumers: Eat tertiary consumers. These are often apex predators.

- Examples: Orcas eating seals, polar bears eating seals.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Eat producers.

- Decomposers and Detritivores: These crucial organisms break down dead organic matter from all trophic levels, returning nutrients to the soil or water, where producers can reuse them. Without them, nutrients would be locked away, and life would cease.

- Examples: Bacteria, fungi, earthworms, dung beetles, vultures.

The flow of energy is unidirectional, generally moving from producers upwards through the consumer levels. However, the flow of nutrients is cyclical, thanks to the tireless work of decomposers.

Energy Transfer: The 10% Rule

A critical concept in food webs is the efficiency of energy transfer. When one organism consumes another, only a fraction of the energy from the consumed organism is incorporated into the consumer’s biomass. A widely cited approximation is the 10% rule, suggesting that only about 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next. The remaining 90% is lost as heat during metabolic processes, or remains in uneaten or undigested parts.

This energy loss explains why food chains rarely extend beyond four or five trophic levels. There simply isn’t enough energy left to support a higher level of consumers.

This principle also explains why there are typically far more producers than primary consumers, more primary consumers than secondary consumers, and so on. This forms an ecological pyramid of numbers or biomass.

Beyond the Basics: Complexity and Dynamics

Food webs are not static diagrams; they are dynamic systems constantly responding to environmental changes and population fluctuations. Their complexity is a key indicator of ecosystem health.

Omnivores, Scavengers, and Detritivores: Specialized Roles

While the primary, secondary, tertiary consumer categories are useful, many organisms defy simple classification:

- Omnivores: Organisms that consume both plants and animals. They can occupy multiple trophic levels simultaneously.

- Examples: Bears eating berries and fish, humans, raccoons.

- Scavengers: Organisms that consume dead animals that they did not kill. They play a vital role in cleaning up carcasses and recycling nutrients.

- Examples: Vultures, hyenas, some crabs.

- Detritivores: Organisms that feed on detritus, which is dead organic matter. This includes decaying plants, animals, and fecal matter. They are distinct from decomposers (like bacteria and fungi) which break down matter at a molecular level.

- Examples: Earthworms, millipedes, woodlice, sea cucumbers.

Food Web Stability and Resilience

The more complex a food web, generally the more stable and resilient the ecosystem. A highly interconnected web with many alternative food sources for predators means that if one prey species declines, predators can switch to another, preventing a collapse. Conversely, simple food webs with few connections are more vulnerable to disturbances.

Imagine a simplified arctic food web: algae → krill → cod → seal → polar bear. If krill populations plummet due to ocean acidification, the entire chain is severely impacted, potentially leading to starvation for seals and polar bears. In a more diverse tropical forest, a predator might have dozens of prey options, making it less dependent on any single one.

Keystone Species: The Linchpins of the Web

Some species have a disproportionately large impact on their ecosystem relative to their abundance. These are called keystone species. Their removal can trigger a cascade of effects, dramatically altering the food web structure and even leading to ecosystem collapse.

- Example 1: Sea Otters. In kelp forests, sea otters prey on sea urchins. Without otters, urchin populations explode, consuming vast amounts of kelp. The loss of kelp forests, which are vital habitats, then impacts numerous other species, from fish to marine invertebrates.

- Example 2: Wolves in Yellowstone. The reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park led to a trophic cascade. By preying on elk, wolves reduced elk numbers, allowing willow and aspen trees to recover along riverbanks. This, in turn, provided habitat for birds and beavers, stabilizing riverbanks and creating new wetlands.

Trophic Cascades: Ripples Through the Web

A trophic cascade is an ecological phenomenon triggered by the addition or removal of top predators and involving reciprocal changes in the relative populations of predator and prey through a food chain, which often results in dramatic changes in ecosystem structure and nutrient cycling.

These cascades can be “top-down” (predator control prey, which controls producers) or “bottom-up” (producer abundance controls higher trophic levels). The Yellowstone wolf example is a classic top-down cascade.

Bioaccumulation and Biomagnification: Unintended Consequences

The process of energy transfer also has a darker side when pollutants are introduced into the environment. Bioaccumulation is the gradual accumulation of substances, such as pesticides or other chemicals, in an organism. Biomagnification is the increase in concentration of these substances in organisms at higher trophic levels.

Consider a pesticide like DDT. If a small amount is absorbed by algae, then zooplankton eat many algae, accumulating more DDT. Small fish eat many zooplankton, accumulating even more. Large fish eat many small fish, and apex predators like eagles eat many large fish. At each step, the concentration of the toxin increases, leading to severe health problems or death for top predators, even if the initial environmental concentration was low.

The Ecologist’s Lens: Advanced Food Web Concepts

For those delving deeper into ecological research, food webs are analyzed using sophisticated metrics and models to understand their structure, function, and response to change.

Food Web Metrics and Network Analysis

Ecologists use various metrics to quantify the properties of food webs:

- Connectance: The proportion of all possible feeding links that are actually present in the web. High connectance generally indicates greater stability.

- Chain Length: The number of links from a producer to a top predator. Average chain length can vary significantly between ecosystems.

- Compartmentalization: The degree to which a food web is divided into distinct sub-webs or modules, with strong interactions within compartments and weaker interactions between them. This can offer some resilience if a disturbance affects only one compartment.

- Omnivory Index: A measure of how much an organism feeds on multiple trophic levels.

Ecological network analysis applies principles from graph theory to study the complex interactions within food webs. This allows researchers to identify key species, predict the impact of species loss, and understand energy flow pathways with greater precision.

Types of Food Webs

Food webs can be conceptualized in different ways depending on the focus of study:

- Source Webs: Trace all the organisms that consume a particular species.

- Sink Webs: Trace all the organisms that are consumed by a particular species.

- Community Webs: Encompass all the feeding relationships within an entire ecological community. These are the most comprehensive and complex.

- Detrital Food Webs: Focus specifically on the decomposers and detritivores, and the organisms that feed on them, highlighting the recycling of nutrients. This is often overlooked but equally vital as grazing food webs.

Human Impacts and Conservation Implications

Human activities profoundly impact food webs globally, often with unforeseen consequences:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Reduces the availability of food and shelter, leading to declines in species populations and simplified food webs. When a habitat is fragmented, species may lose access to diverse food sources, making them more vulnerable.

- Climate Change: Alters species distributions, phenology (timing of biological events like migration or breeding), and productivity. A mismatch in timing, for example, if insects hatch earlier due to warmer temperatures but migratory birds arrive later, can disrupt crucial feeding links.

- Invasive Species: Introduce new predators, competitors, or diseases, often outcompeting native species or disrupting established predator-prey relationships. The introduction of the brown tree snake to Guam, for instance, decimated native bird populations, leading to a cascade of ecological changes.

- Pollution: As seen with biomagnification, pollutants like pesticides, heavy metals, and plastics can accumulate up the food web, harming top predators and even humans.

- Overexploitation: Overfishing or overhunting can remove key species from a food web, leading to trophic cascades and ecosystem instability. The collapse of cod fisheries in the North Atlantic, for example, had widespread impacts on the marine food web.

Understanding these impacts through the lens of food webs is crucial for effective conservation. Protecting biodiversity means not just saving individual species, but preserving the intricate connections that sustain entire ecosystems. Conservation efforts often focus on protecting keystone species, restoring habitats to support a diverse array of organisms, and mitigating pollution to prevent its ascent through the food web.

The Grand Tapestry of Life

From the microscopic plankton in the ocean to the majestic predators of the savanna, every organism plays a role in the grand, interconnected drama of life. Food webs are not just diagrams; they are living, breathing representations of energy, survival, and the delicate balance that sustains our planet.

By appreciating the complexity and fragility of these ecological networks, a deeper understanding of our place within nature emerges. It becomes clear that the health of a distant forest or ocean ultimately affects us all, underscoring the profound responsibility humanity holds as stewards of Earth’s magnificent and intricate food webs.