Unlocking Nature’s Wisdom: The Power of Agroforestry

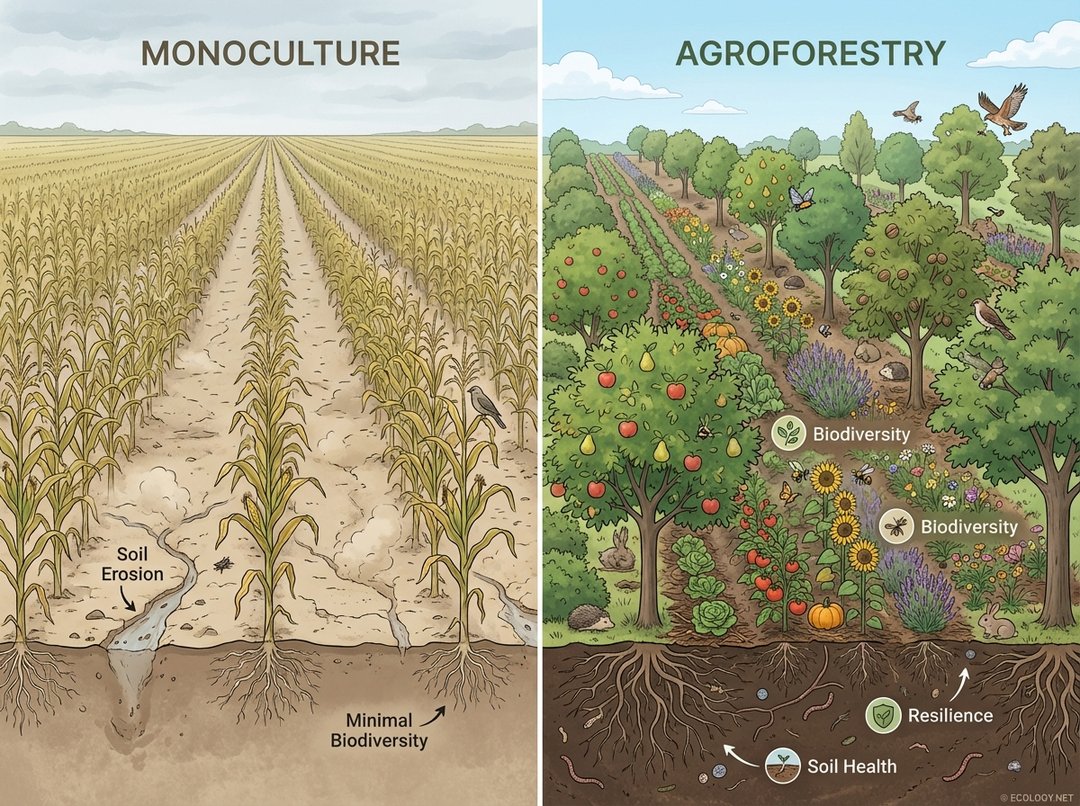

For centuries, agriculture has largely focused on maximizing yield from single crops, often at a significant cost to the environment. Vast monoculture fields, while efficient in some respects, have contributed to soil degradation, biodiversity loss, and increased vulnerability to climate change. But what if there was a way to grow food, fiber, and fuel that not only sustained us but also healed the planet? Enter agroforestry, an ancient practice reimagined for the modern world, offering a powerful solution to many of today’s ecological and agricultural challenges.

Core Principles: A New Vision for Agriculture

Agroforestry is a land use management system in which trees or shrubs are grown around or among crops or pastureland. This intentional integration of woody perennials with agricultural crops and/or livestock on the same land management unit is more than just planting trees on a farm. It is a dynamic, ecologically based natural resource management system that diversifies and sustains production to increase social, economic, and environmental benefits for land users at all levels.

The fundamental concept behind agroforestry is to mimic the natural complexity and resilience of forest ecosystems. By combining different elements that interact synergistically, agroforestry systems create a more robust and productive landscape compared to conventional monoculture farming. Imagine a field where towering fruit trees provide shade for shade-tolerant vegetables below, while their roots stabilize the soil and attract beneficial insects. This is the essence of agroforestry: working with nature, not against it.

Key Benefits: A Symbiotic Approach

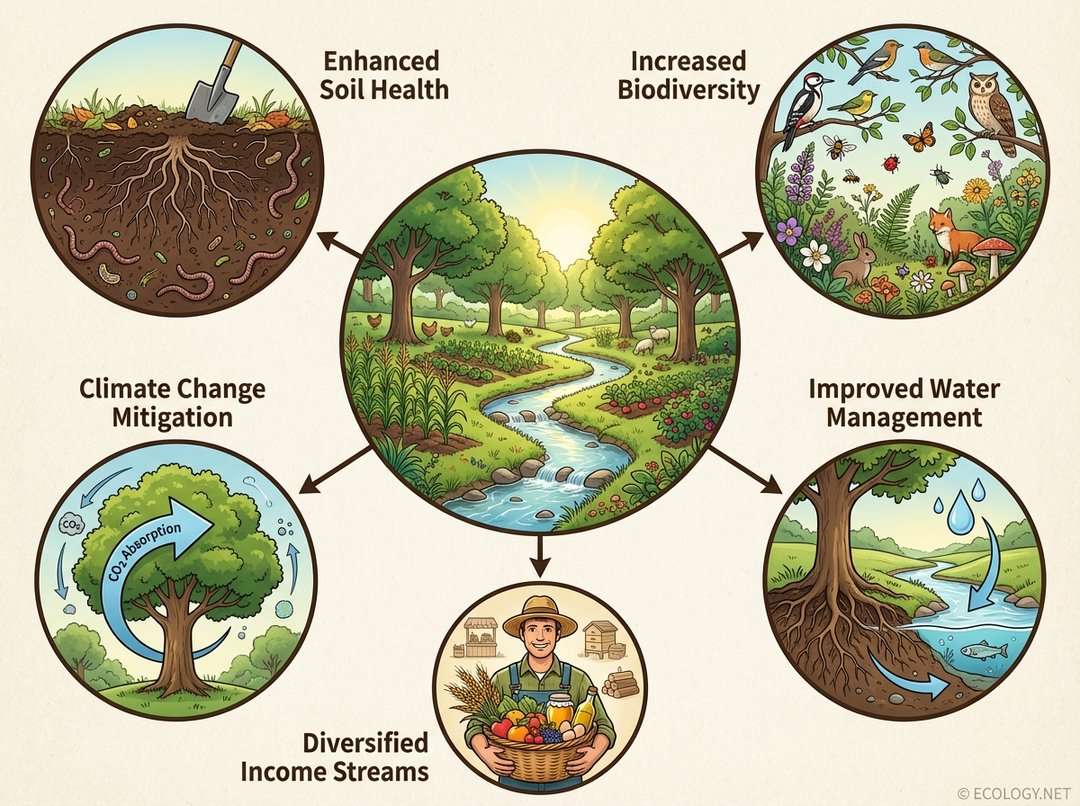

The advantages of integrating trees into agricultural landscapes are extensive, touching upon ecological, economic, and social dimensions. Agroforestry systems are not just about sustainability; they are about creating thriving, resilient ecosystems that benefit both people and the planet.

- Enhanced Soil Health: Trees contribute organic matter to the soil through leaf litter and root decomposition, enriching its fertility and structure. Their extensive root systems prevent erosion, improve water infiltration, and sequester carbon, transforming degraded land into vibrant, productive soil. This leads to a reduction in the need for synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

- Increased Biodiversity: By providing diverse habitats, agroforestry systems become magnets for wildlife. Birds, beneficial insects, pollinators like bees and butterflies, and various microorganisms find shelter and food, creating a balanced ecosystem that naturally controls pests and enhances crop pollination. A farm becomes a haven for life, not just a food factory.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Trees are powerful carbon sinks, absorbing significant amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in their biomass and the soil. Agroforestry practices can play a crucial role in reducing greenhouse gas concentrations, making farms part of the climate solution.

- Improved Water Management: Tree roots act as natural sponges, helping to retain moisture in the soil, reducing runoff, and recharging groundwater. This is particularly vital in drought-prone areas or regions experiencing erratic rainfall, ensuring more consistent water availability for crops and livestock. Riparian buffers, for example, filter pollutants before they reach waterways.

- Diversified Income Streams: Farmers can harvest a variety of products from an agroforestry system, including fruits, nuts, timber, medicinal plants, and forage for livestock, in addition to traditional crops. This diversification reduces reliance on a single commodity, making farms more economically resilient to market fluctuations or crop failures.

- Increased Resilience: A diverse system is inherently more resilient. If one crop fails due to disease or extreme weather, others may still thrive, providing a safety net for farmers. The presence of trees can also moderate microclimates, offering shade and windbreaks that protect crops and livestock from harsh conditions.

Different Flavors of Agroforestry: Systems in Practice

Agroforestry is not a one-size-fits-all solution. It encompasses a range of distinct systems, each tailored to specific environmental conditions, agricultural goals, and local needs. Understanding these different approaches is key to appreciating the versatility and adaptability of agroforestry.

- Alley Cropping: This system involves growing rows of trees or shrubs simultaneously with annual or perennial crops cultivated in the alleys between the tree rows. The trees can provide shade, nutrients, and windbreaks, while the crops benefit from improved soil conditions.

- Example: Rows of black walnut trees planted with corn or soybeans growing in the wide spaces between them. The walnuts will eventually yield valuable timber and nuts, while the annual crops provide immediate income.

- Silvopasture: Combining trees, forage, and livestock in an integrated system. Trees provide shade and shelter for animals, improve pasture quality, and can yield timber or other products. Livestock, in turn, can help manage undergrowth and fertilize the soil.

- Example: Cattle grazing in a pasture dotted with mature oak trees. The trees offer crucial shade during hot summers, reducing animal stress, and their acorns can provide additional forage.

- Forest Farming: This practice cultivates specialty crops under the canopy of an existing or newly planted forest. It leverages the natural shade and microclimate of the forest environment to grow high-value, shade-tolerant non-timber forest products.

- Example: Growing ginseng, shiitake mushrooms, or ramps beneath a hardwood forest canopy. These products thrive in the dappled light and moist conditions provided by the trees.

- Riparian Forest Buffers: Strips of trees, shrubs, and grasses planted along streams, rivers, and other water bodies. These buffers are crucial for protecting water quality, stabilizing streambanks, and providing habitat for aquatic and terrestrial wildlife.

- Example: A dense band of willows, alders, and native grasses planted along a farm stream, separating it from adjacent crop fields. This buffer filters agricultural runoff, preventing pollutants from entering the waterway.

- Windbreaks/Shelterbelts: Rows of trees and shrubs strategically planted to reduce wind speed, protect crops and livestock, and prevent soil erosion. They can also provide habitat and aesthetic value.

- Example: A multi-row planting of conifers and deciduous trees on the windward side of a farm, protecting a vegetable field from damaging winds and reducing moisture evaporation.

The Ecological and Economic Imperative

The global challenges of food security, climate change, and biodiversity loss demand innovative and holistic solutions. Agroforestry stands out as a powerful tool in addressing these complex issues. By integrating ecological principles with agricultural production, it offers a pathway towards more resilient food systems, healthier ecosystems, and stronger rural economies.

From a global perspective, the widespread adoption of agroforestry could significantly contribute to carbon sequestration targets, helping to mitigate the impacts of climate change. Locally, it empowers farmers to diversify their income, reduce input costs, and build greater resilience against environmental shocks. It fosters a deeper connection to the land, promoting stewardship and long-term sustainability.

Challenges and Future Outlook

While the benefits are clear, the transition to agroforestry is not without its challenges. It often requires a shift in mindset, new knowledge and skills, and an initial investment of time and resources for tree establishment. Planning for long-term yields from trees requires patience and a different approach to farm management.

However, the growing recognition of agroforestry’s potential is leading to increased research, education, and support for farmers. Governments, non-governmental organizations, and academic institutions are increasingly promoting agroforestry as a cornerstone of sustainable agriculture. As our understanding of ecological systems deepens, and as the pressures of climate change intensify, agroforestry is poised to become an indispensable component of future food production systems.

Cultivating a Greener Tomorrow

Agroforestry represents a profound shift in how humanity interacts with the land. It moves beyond the simplistic view of agriculture as merely a means to extract resources, embracing a vision where farms are vibrant, interconnected ecosystems that produce abundance while enhancing environmental health. By weaving trees back into the fabric of our agricultural landscapes, we are not just growing food; we are cultivating a more resilient, biodiverse, and sustainable future for all. It is a testament to the wisdom of nature, offering a practical and powerful path towards ecological regeneration and enduring prosperity.