The Vibrant Underwater Cities: Unveiling the Wonders of Coral Reefs

Beneath the ocean’s surface lie some of Earth’s most breathtaking and biodiverse ecosystems: coral reefs. Often called the “rainforests of the sea,” these intricate underwater structures are far more than just beautiful formations; they are bustling metropolises teeming with life, built by tiny animals over millennia. Understanding coral reefs means appreciating their delicate construction, their incredible inhabitants, and the vital role they play for our planet.

The Building Blocks: Coral Polyps

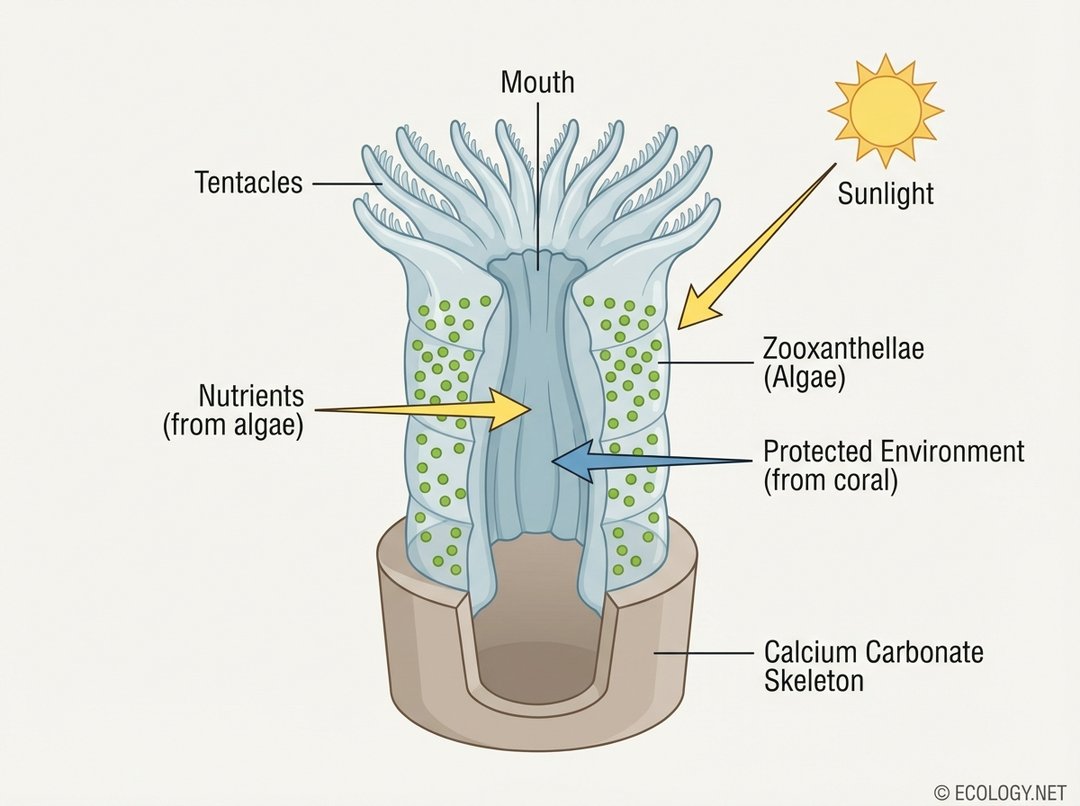

At the heart of every coral reef is a minuscule, soft-bodied animal called a coral polyp. Related to jellyfish and sea anemones, these individual polyps are the architects of the massive structures we admire. Each polyp is typically cylindrical, with a ring of tentacles surrounding a central mouth, which it uses to capture tiny plankton from the water.

What makes reef-building corals unique is their ability to extract calcium carbonate from seawater and secrete it to form a hard, cup-shaped skeleton. As polyps grow and divide, they create new skeletal material, gradually building upon the foundations of their predecessors. Over countless generations, these tiny contributions accumulate, forming the complex, stony structures that define a coral reef.

Symbiotic Relationships: Algae and Coral

A crucial secret to the success of most reef-building corals lies in an extraordinary partnership. Within the tissues of coral polyps live microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. This is a classic example of mutualism, where both partners benefit significantly.

- For the Algae: The coral polyp provides a protected environment and compounds essential for photosynthesis, such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen.

- For the Coral: The zooxanthellae, through photosynthesis, produce oxygen and a significant amount of energy-rich compounds, primarily sugars, which the coral polyp uses as its main food source. This energy allows the coral to grow, reproduce, and build its calcium carbonate skeleton much faster than it could on its own.

This symbiotic relationship is why most coral reefs thrive in shallow, clear waters where sunlight can penetrate, allowing the zooxanthellae to photosynthesize effectively. The vibrant colors of healthy corals are often due to the pigments of these symbiotic algae.

How Reefs Grow: From Tiny Polyps to Grand Structures

Coral reefs grow through a combination of individual polyp growth and the asexual budding of new polyps from existing ones, leading to the formation of colonies. These colonies can take on a myriad of shapes, from branching antlers to massive brain-like domes or delicate plate-like structures. Over vast stretches of time, these colonies merge and expand, creating the immense reef systems we see today.

The growth of a coral reef is a slow and continuous process, often taking thousands to millions of years to form large structures. The rate of growth depends on various factors including water temperature, light availability, nutrient levels, and the presence of grazers that keep algae in check.

Types of Coral Reefs

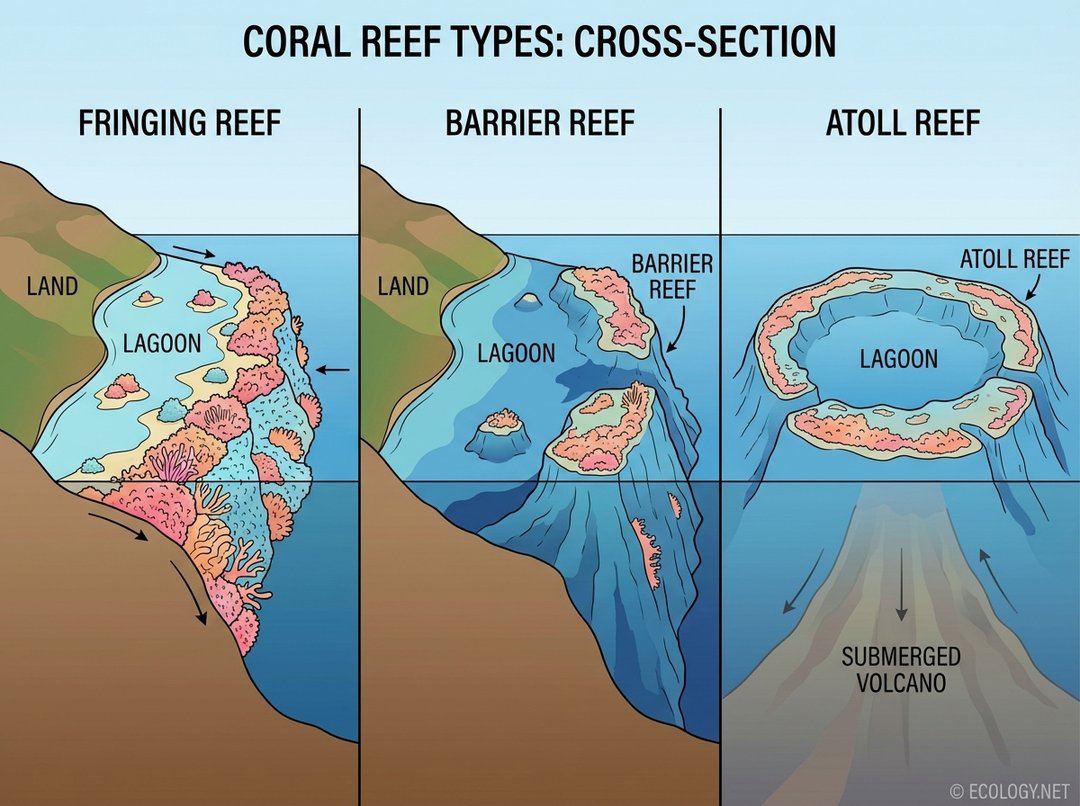

Coral reefs are not all uniform in their structure or their relationship to landmasses. Ecologists classify them into three primary geological types, each with distinct characteristics:

- Fringing Reefs: These are the most common type of coral reef. They grow directly from the shoreline of a continent or island, forming a border along the coast. They are typically relatively narrow and often have a shallow lagoon or no lagoon at all between the reef and the land.

- Example: Many reefs found along the coasts of the Red Sea or the Caribbean islands.

- Barrier Reefs: These reefs are separated from the mainland or island by a deep, wide lagoon. They run parallel to the coast, forming a “barrier” between the open ocean and the shallower coastal waters. Barrier reefs can be very large and extensive.

- Example: The Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia, the largest living structure on Earth, is a prime example.

- Atolls: An atoll is a ring-shaped coral reef, often enclosing a central lagoon, with no land in the center. Atolls typically form around submerged volcanic islands. As the volcano slowly sinks or erodes over millions of years, the coral continues to grow upwards, maintaining its position near the surface, eventually leaving only the coral ring surrounding the lagoon where the island once stood.

- Example: The Maldives and many islands in the Pacific Ocean are classic atolls.

The Incredible Biodiversity of Coral Reefs

The structural complexity of coral reefs provides an astonishing array of habitats, nooks, and crannies, supporting an unparalleled diversity of marine life. Despite covering less than 0.1% of the ocean floor, coral reefs are home to at least 25% of all marine species, making them true hotspots of biodiversity.

These vibrant ecosystems are crucial for:

- Fish Species: Thousands of species of fish, from tiny gobies to large groupers and sharks, rely on reefs for food, shelter, and breeding grounds.

- Invertebrates: A staggering variety of invertebrates, including crabs, lobsters, sea stars, sea urchins, octopuses, and countless types of worms and mollusks, inhabit the reef.

- Marine Mammals and Reptiles: Sea turtles, dolphins, and dugongs often visit or reside near reefs to feed.

- Algae and Sponges: Beyond the zooxanthellae, many other types of algae and sponges contribute to the reef’s structure and food web.

This rich tapestry of life creates a complex food web, where every organism plays a role in maintaining the health and balance of the reef ecosystem.

Threats to Coral Reefs: A Global Crisis

Despite their resilience and ancient origins, coral reefs worldwide are facing unprecedented threats, largely due to human activities. The health of these vital ecosystems is rapidly declining, with severe consequences for marine life and human communities alike.

Climate Change and Coral Bleaching

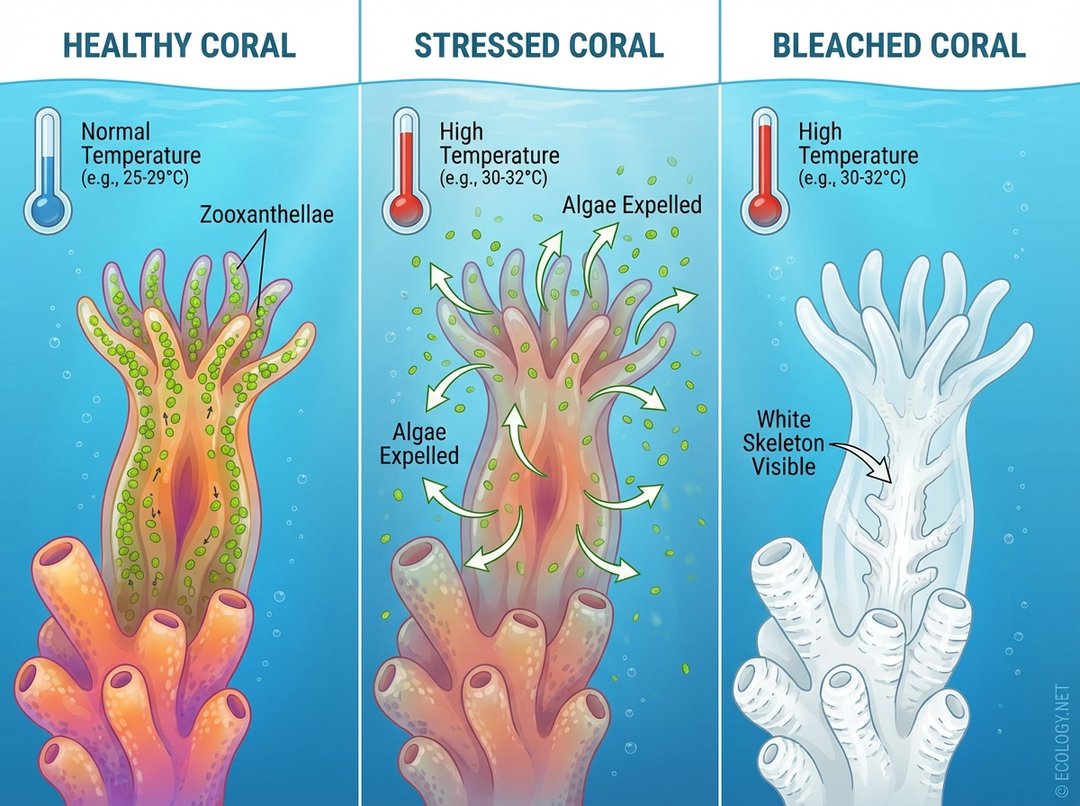

One of the most significant threats is climate change, primarily driven by rising global temperatures. As ocean temperatures increase, corals become stressed. This stress causes the coral polyps to expel their symbiotic zooxanthellae algae, leading to a phenomenon known as coral bleaching.

When corals bleach, they turn white because their tissues become transparent, revealing the white calcium carbonate skeleton beneath. While bleached corals are not immediately dead, they are severely weakened and vulnerable. If the stressful conditions persist, or if they are exposed to other stressors, they will eventually die. Widespread bleaching events have become more frequent and severe globally, leading to significant coral mortality.

Ocean Acidification

Another grave consequence of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide is ocean acidification. The oceans absorb a significant portion of the CO2 from the atmosphere, which then reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid. This process lowers the pH of the ocean, making it more acidic.

Ocean acidification directly impacts corals and other shell-forming organisms. It reduces the availability of carbonate ions, which corals need to build and maintain their calcium carbonate skeletons. This makes it harder for corals to grow and repair themselves, and can even cause existing skeletons to dissolve, effectively hindering reef growth and resilience.

Pollution

Various forms of pollution also pose a serious threat to reefs:

- Sedimentation: Runoff from land clearing, agriculture, and coastal development can carry large amounts of sediment into coastal waters. This sediment can smother corals, reduce light penetration for zooxanthellae, and clog feeding polyps.

- Nutrient Runoff: Fertilizers and sewage from land can introduce excess nutrients into reef waters. While some nutrients are essential, an overload can lead to algal blooms that outcompete and smother corals.

- Plastic Pollution: Plastic debris can physically damage corals, introduce diseases, and block sunlight.

- Chemical Pollutants: Industrial chemicals, pesticides, and oil spills can be directly toxic to corals and other reef organisms.

Overfishing and Destructive Fishing Practices

Unsustainable fishing practices can severely disrupt the delicate balance of reef ecosystems. Overfishing of herbivorous fish, such as parrotfish, can lead to an overgrowth of algae that smothers corals. Destructive methods like blast fishing or cyanide fishing directly destroy coral structures and kill non-target species, leaving behind barren rubble.

Physical Damage

Reefs are also vulnerable to direct physical damage from human activities. Anchors from boats can break off large sections of coral. Careless tourism, such as touching or standing on corals, can cause irreparable harm. Even natural events like powerful storms, while part of the natural cycle, can cause extensive damage, especially to already weakened reefs.

Why Coral Reefs Matter: Their Value to Humans and the Planet

The decline of coral reefs is not just an ecological tragedy; it has profound implications for human societies worldwide. The services provided by healthy coral reefs are invaluable:

- Coastal Protection: Reefs act as natural breakwaters, reducing wave energy and protecting coastlines from erosion, storm surges, and tsunamis. This protection is vital for coastal communities and infrastructure.

- Fisheries and Food Security: Reefs are critical breeding grounds and nurseries for countless fish species that form the basis of commercial and subsistence fisheries. Millions of people globally rely on reefs for their primary source of protein and livelihood.

- Tourism and Recreation: The beauty and biodiversity of coral reefs attract millions of tourists annually, supporting local economies through diving, snorkeling, and other recreational activities.

- Biomedical Discoveries: The unique organisms found on coral reefs are a rich source of compounds with potential pharmaceutical applications, including treatments for cancer, arthritis, and bacterial infections.

- Cultural Significance: For many indigenous cultures, coral reefs hold deep spiritual and cultural significance, intertwined with their traditions and way of life.

What Can Be Done: Conservation Efforts and Individual Actions

Protecting coral reefs requires a multi-faceted approach, involving global policy changes, local conservation efforts, and individual responsibility.

- Global Action: International agreements and national policies are crucial to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, combat climate change, and mitigate ocean acidification.

- Local Conservation: Establishing Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), implementing sustainable fisheries management, controlling pollution from land-based sources, and restoring damaged reefs are vital local initiatives.

- Research and Monitoring: Ongoing scientific research helps us better understand reef ecosystems, identify threats, and develop effective conservation strategies.

- Individual Actions: Every person can contribute to reef conservation:

- Reduce your carbon footprint to lessen climate change impacts.

- Make sustainable seafood choices to support healthy fish populations.

- Support responsible tourism practices when visiting coastal areas.

- Reduce plastic consumption and properly dispose of waste.

- Educate others about the importance of coral reefs.

A Future for Our Underwater Cities

Coral reefs are magnificent testaments to nature’s artistry and resilience, vital for the health of our oceans and the well-being of humanity. While the challenges they face are immense, understanding their intricate biology, their ecological significance, and the threats they endure empowers us to act. By working together, we can strive to protect these vibrant underwater cities, ensuring their beauty and bounty endure for generations to come.