Life on Earth is a constant dance of movement. From the smallest microbes to the largest mammals, organisms are always on the move, seeking new opportunities, escaping danger, or simply following the rhythms of their environment. Among these fundamental movements, one process stands out as a critical driver of population dynamics and species survival: emigration.

Emigration, at its core, is the act of individuals leaving a population or habitat. It is a concept often discussed alongside its counterpart, immigration, which describes individuals arriving. Together, these movements dictate the ebb and flow of life within any given ecological system, shaping communities and influencing the very fabric of biodiversity.

Understanding the Basics: What is Emigration?

Imagine a bustling town. When residents decide to pack their bags and move away, they are emigrating from that town. In ecology, the principle is much the same. Emigration refers specifically to the one-way outward movement of individuals from a population. This departure can be permanent or temporary, and it plays a crucial role in how populations grow, shrink, and interact with their surroundings.

It is vital to distinguish emigration from other forms of movement. While migration often implies a seasonal, round-trip journey, emigration is typically a departure with no immediate intention of return to the original population. It is a fundamental component of population dynamics, influencing everything from genetic diversity to the distribution of species across landscapes.

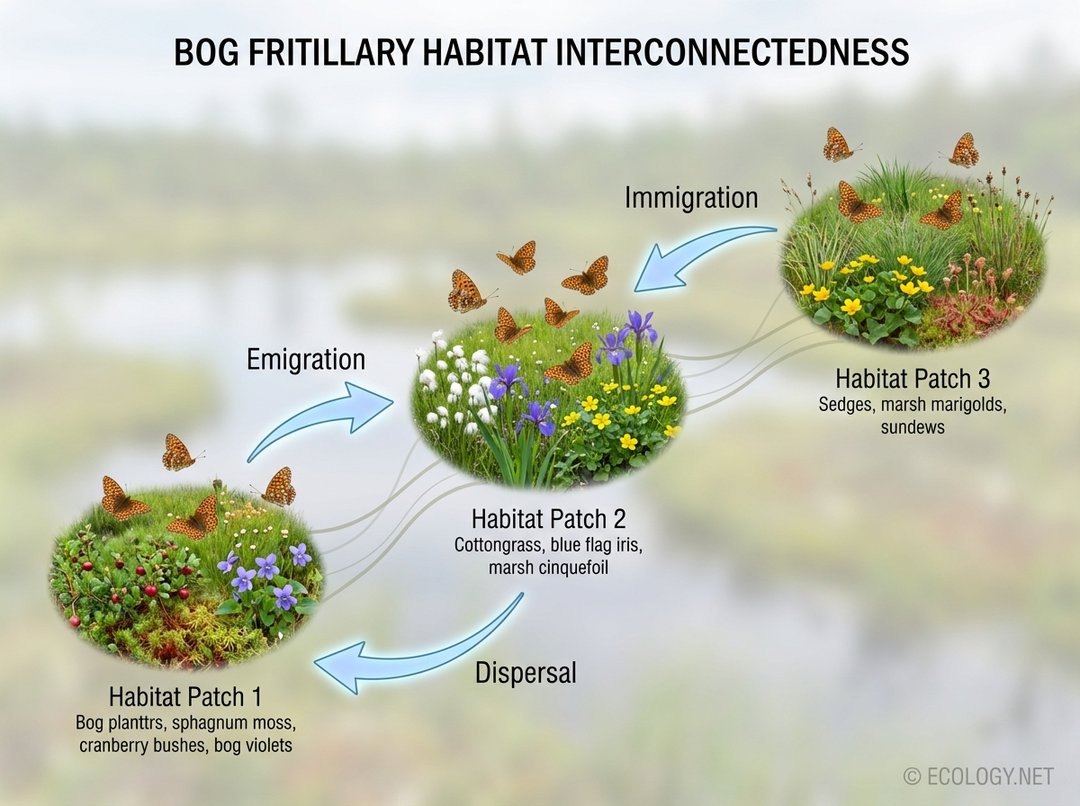

The diagram above clearly illustrates this distinction. Individuals moving out of a central population represent emigration, while those moving in represent immigration. These two processes are constantly at play, balancing each other to determine the net change in a population’s size.

The Driving Forces: Why Do Organisms Emigrate?

Organisms do not simply leave their homes without reason. Emigration is often a response to environmental pressures or an innate drive for dispersal. These “push” factors can be broadly categorized into several key areas:

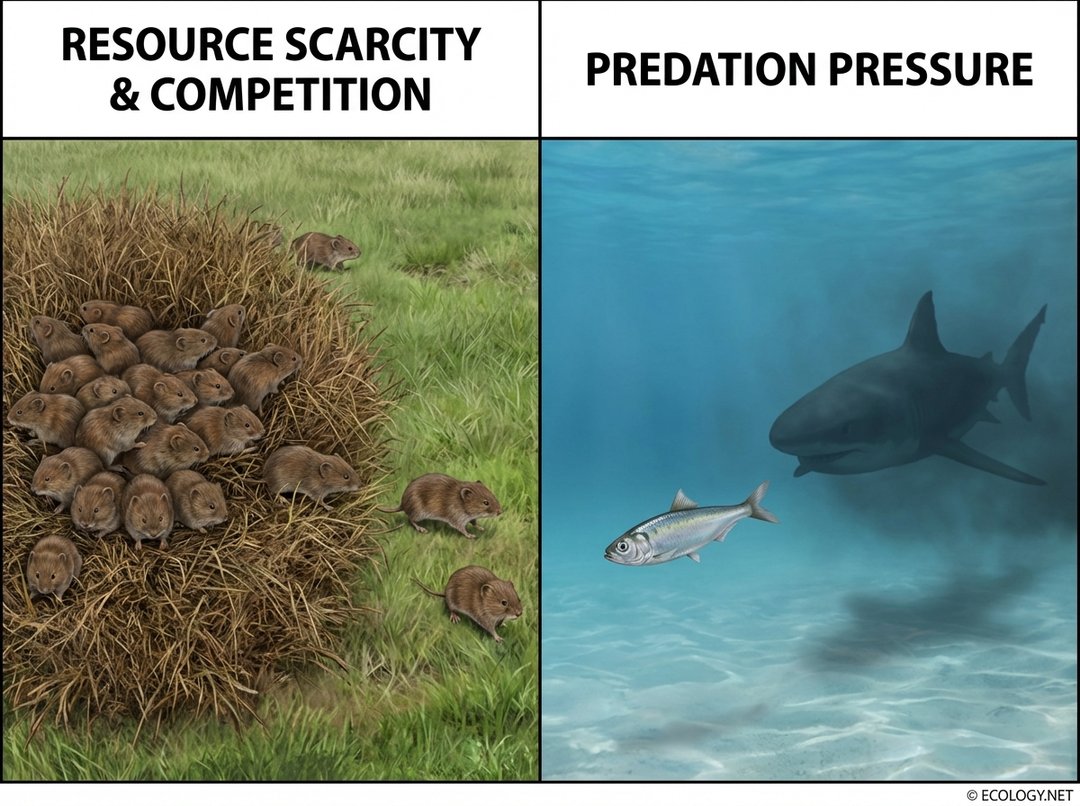

- Resource Scarcity and Competition: When a population grows too large for its habitat to support, resources like food, water, or nesting sites become scarce. Intense competition for these limited resources can force individuals, often the weaker or younger ones, to seek new territories. For instance, a dense population of deer might lead younger bucks to emigrate in search of less competitive foraging grounds.

- Predation Pressure: High numbers of predators in an area can make survival challenging. Prey species may emigrate from areas with intense predation risk to safer havens. Consider a group of gazelles moving away from a territory newly dominated by a pride of lions.

- Habitat Degradation or Loss: Environmental changes, whether natural disasters like floods or human-induced alterations like deforestation, can render a habitat unsuitable. Organisms are then compelled to emigrate to find viable living spaces.

- Social Pressures: In many social species, younger individuals or subordinates may be forced out of their natal groups by dominant members. This is common in wolf packs, lion prides, and various primate groups, where emigration prevents inbreeding and reduces competition within the group.

- Climate Change: As global temperatures shift and weather patterns become erratic, many species are emigrating from their traditional ranges to areas with more favorable climates. This is particularly evident in species moving towards higher latitudes or altitudes.

The image above vividly portrays two primary drivers of emigration. On the left, voles are seen leaving an overcrowded area, a clear response to resource scarcity and competition. On the right, a fish flees a predatory shark, illustrating emigration driven by the need to escape danger.

The Ripple Effect: Ecological Consequences of Emigration

Emigration is not just an individual act, it has profound consequences for both the population left behind and the broader ecosystem:

For the Source Population:

- Reduced Competition: The departure of individuals can alleviate pressure on remaining resources, potentially improving the survival and reproductive success of those who stay.

- Genetic Loss or Gain: If emigrants carry unique genetic traits, their departure can lead to a loss of genetic diversity in the source population. Conversely, if less fit individuals emigrate, it can strengthen the gene pool.

- Altered Demographics: Emigration often disproportionately affects certain age groups or sexes, altering the age structure and sex ratio of the remaining population. For example, young males are often the primary emigrants in many mammal species.

For the Destination Population (if successful):

- Genetic Enrichment: Arriving emigrants introduce new genes, increasing genetic diversity and potentially enhancing the fitness and adaptability of the recipient population.

- Increased Competition: New arrivals can intensify competition for resources, potentially stressing the existing population.

- Disease Transmission: Emigrants can inadvertently carry diseases or parasites to new populations, posing a threat to native species.

For the Species and Ecosystem:

- Range Expansion and Colonization: Emigration is a primary mechanism for species to expand their geographical range, colonize new habitats, and establish new populations. This is crucial for adapting to environmental change.

- Population Regulation: It acts as a natural regulator, preventing overpopulation in certain areas and facilitating the spread of species into underutilized habitats.

- Ecosystem Connectivity: By linking different populations, emigration contributes to the overall health and resilience of ecosystems.

Emigration in Complex Ecological Systems: Metapopulations

While emigration is a straightforward concept at the individual level, its implications become particularly intricate and vital when considering larger ecological structures, such as metapopulations. A metapopulation is a group of spatially separated populations of the same species which interact at some level, typically through individuals moving between them.

In a metapopulation, individual habitat patches may experience local extinctions due to various factors like disease, predation, or habitat degradation. However, emigration from healthy patches can lead to immigration into empty or declining patches, effectively “rescuing” them or allowing for recolonization. This dynamic interplay of local extinctions and recolonizations, driven by emigration and immigration, is what allows the species to persist regionally even if individual populations are unstable.

The diagram above illustrates this concept beautifully with bog fritillary butterflies. Each habitat patch supports a population, and the arrows indicate the movement of butterflies between these patches. Emigration from one patch can become immigration into another, maintaining the overall viability of the species across a fragmented landscape. Without this movement, isolated populations would be far more vulnerable to extinction.

Emigration and Conservation Efforts

Understanding emigration is paramount for effective conservation strategies. Habitat fragmentation, caused by human development, often creates isolated patches of habitat, hindering the natural movement of individuals. This can prevent emigration from occurring when it is most needed, leading to:

- Increased Inbreeding: Without new genetic material from emigrants, small, isolated populations can suffer from inbreeding depression, reducing their fitness.

- Reduced Resilience: Populations unable to receive immigrants or send out emigrants are less able to recover from disturbances or adapt to environmental changes.

- Local Extinctions: If a local population goes extinct and there are no emigrants from nearby populations to recolonize the area, the species may be permanently lost from that region.

Conservation efforts often focus on creating “wildlife corridors” or “habitat bridges” to facilitate emigration and immigration between fragmented habitats. These corridors allow animals to move safely between patches, maintaining genetic flow and strengthening metapopulation dynamics, thereby enhancing the long-term survival prospects of many species.

The Enduring Journey

Emigration is far more than just individuals moving from one place to another. It is a fundamental ecological process that shapes population structures, drives evolution, and dictates the distribution of life across the planet. From the smallest insects dispersing their genes to large mammals seeking new territories, the act of leaving plays an indispensable role in the intricate web of life.

By understanding the drivers and consequences of emigration, ecologists and conservationists can better predict how species will respond to environmental changes and develop more effective strategies to protect biodiversity. The journey of an emigrant, whether a vole, a butterfly, or a fish, is a testament to the dynamic and interconnected nature of our living world, a continuous quest for survival and adaptation that underpins all ecological processes.