Imagine an arch bridge, magnificent and strong. While every stone plays a part, there is one crucial stone at the very top, the keystone, that holds the entire structure together. Remove it, and the entire bridge collapses. In the intricate world of ecology, certain species play a remarkably similar role. These are known as keystone species, and their presence or absence can dramatically reshape an entire ecosystem.

The concept of a keystone species revolutionized our understanding of how ecosystems function, shifting focus from simply counting species to appreciating the unique and often outsized influence of particular organisms. These aren’t necessarily the most abundant species, nor are they always the largest; their power lies in their disproportionate impact on the environment around them.

The Classic Revelation: Starfish and the Intertidal Zone

The idea of a keystone species was first introduced in 1969 by ecologist Robert Paine, based on his groundbreaking research in the intertidal zones of the Pacific Northwest. Paine observed a vibrant community of marine life, including various species of mussels, barnacles, limpets, and algae, all coexisting with a predatory starfish, Pisaster ochraceus.

Paine conducted a simple yet profound experiment: he removed the starfish from specific areas of the intertidal zone and observed the consequences. The results were astonishing. Without the starfish, one species of mussel, Mytilus californianus, rapidly outcompeted and displaced nearly all other species. The mussels, no longer kept in check by their primary predator, monopolized the space, leading to a dramatic decline in biodiversity.

This experiment vividly demonstrated that the starfish, despite not being the most numerous organism, was critical for maintaining the diversity of the ecosystem. It controlled the population of a dominant competitor, thereby creating space and resources for many other species to thrive. This phenomenon, where the removal of a predator causes a cascade of effects down the food web, is often referred to as a trophic cascade.

Beyond the Starfish: Diverse Roles of Keystone Species

While Paine’s starfish provided the initial insight, ecologists have since identified keystone species across a vast array of ecosystems, performing various ecological roles. Their impact can manifest in several ways:

- Keystone Predators: Like the starfish, these predators regulate the populations of herbivores or other competitors, preventing a single species from dominating and allowing for greater biodiversity.

- Example: Wolves in Yellowstone National Park. The reintroduction of wolves in Yellowstone led to a remarkable recovery of the park’s ecosystem. By preying on elk, wolves reduced elk grazing pressure on willow and aspen trees along riverbanks. This allowed the vegetation to recover, stabilizing riverbanks, creating cooler stream temperatures, and benefiting beaver populations and fish.

- Example: Sea Otters in Kelp Forests. Sea otters prey on sea urchins. Without otters, urchin populations explode, consuming vast amounts of kelp and transforming lush kelp forests into barren “urchin barrens,” devastating the entire ecosystem that relies on kelp for food and shelter.

- Keystone Herbivores: Some herbivores can be keystone species by preventing plant overgrowth or shaping the physical structure of the landscape.

- Keystone Ecosystem Engineers: These species physically modify their environment, creating, maintaining, or destroying habitats that are essential for other species.

-

- Example: Beavers. Beavers build dams, transforming flowing streams into ponds and wetlands. These new habitats support a rich diversity of aquatic insects, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals that could not survive in the original stream environment. Their engineering creates entire new ecosystems.

- Keystone Mutualists: These species engage in mutually beneficial interactions with other species, and their absence can disrupt these critical relationships.

- Example: Pollinators. While many pollinators exist, certain species might be keystone if they are the sole or primary pollinator for a large number of plant species, or for a foundational plant species. The loss of such a pollinator could lead to the collapse of plant communities.

Distinguishing Keystone Species from Other Important Species

It is easy to confuse keystone species with other ecologically important categories. Understanding the distinctions is crucial for effective conservation.

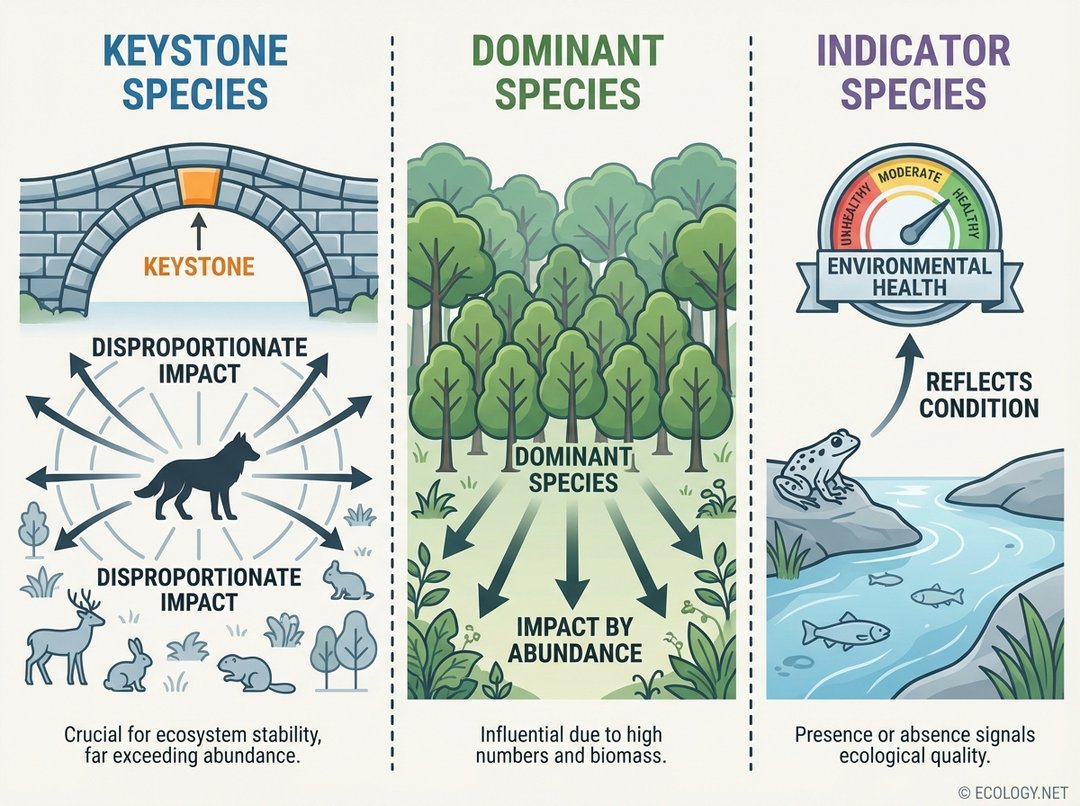

- Keystone Species: As discussed, these have a disproportionately large impact on their ecosystem relative to their abundance or biomass. Their removal causes significant ecosystem alteration. Think of them as the linchpin.

- Dominant Species: These species have a large impact primarily because of their high abundance or biomass. They are often the most numerous or largest organisms in an ecosystem.

- Example: Trees in a forest. A forest is defined by its dominant tree species. Their sheer numbers and size create the habitat structure, influence light, temperature, and nutrient cycles. While their removal would certainly alter the ecosystem, it is due to their overwhelming presence, not necessarily a unique functional role that no other species could fill.

- Indicator Species: These species serve as early warning signs of environmental change or ecosystem health. Their presence, absence, or abundance reflects specific environmental conditions.

While a species can sometimes fit into more than one category, the defining characteristic of a keystone species is that its impact is far greater than what its numbers alone would suggest.

Why Do Keystone Species Matter?

The importance of keystone species extends far beyond their individual roles. They are fundamental to:

- Maintaining Biodiversity: By regulating populations, creating habitats, or facilitating crucial interactions, keystone species prevent competitive exclusion and allow a wider array of life to flourish.

- Ecosystem Stability and Resilience: Their presence helps buffer ecosystems against disturbances and maintain their overall structure and function. The loss of a keystone species can trigger a cascade of extinctions and ecosystem collapse.

- Ecosystem Services: Many keystone species contribute directly or indirectly to vital services that benefit humans, such as clean water, fertile soil, and climate regulation. For instance, healthy kelp forests, maintained by sea otters, provide nurseries for fish populations that support fisheries.

Conservation Implications

Understanding keystone species is paramount for effective conservation strategies. Instead of trying to save every single species, identifying and protecting keystone species can be a highly efficient way to preserve entire ecosystems. Conservation efforts often focus on:

- Identifying Keystone Species: This requires extensive ecological research to understand complex food webs and species interactions.

- Protecting Keystone Species Populations: Ensuring healthy populations of these critical species through habitat preservation, anti-poaching measures, and reintroduction programs.

- Restoring Keystone Species: Reintroducing keystone species to areas where they have been extirpated can have profound positive effects, as seen with the wolves in Yellowstone.

Challenges and Nuances in Identifying Keystone Species

While the concept is powerful, identifying a true keystone species in every ecosystem can be more complex than it appears. Ecologists face several challenges:

- Defining “Disproportionate Impact”: Quantifying the exact level of impact that qualifies a species as “keystone” can be subjective and context-dependent.

- Complexity of Ecosystems: Real-world ecosystems are incredibly intricate, with countless interactions. Isolating the impact of a single species can be difficult.

- Context Dependency: A species might be a keystone in one ecosystem or under certain conditions, but not in another. For example, a predator might be keystone if its prey lacks other significant predators, but less so if multiple predators exist.

- Long-Term Studies: The full impact of a species’ removal or reintroduction might take years or even decades to become apparent, requiring long-term ecological research.

Despite these challenges, the keystone species concept remains a cornerstone of modern ecology and conservation biology. It provides a framework for understanding the delicate balance of nature and highlights the profound consequences of losing even seemingly small components of an ecosystem.

The Unseen Architects of Life

Keystone species serve as a powerful reminder that not all species are created equal in their ecological influence. They are the unseen architects, the quiet guardians, and sometimes the fierce regulators that maintain the structure and function of the natural world. By recognizing and protecting these pivotal players, we can safeguard the intricate web of life that sustains us all, ensuring the resilience and biodiversity of our planet for generations to come.