Imagine a world where energy flows like a river, constantly moving, transforming, and sustaining life. At the heart of this intricate system lies a fundamental ecological concept: the energy pyramid. This powerful visual metaphor helps us understand not just who eats whom, but also the sheer amount of energy available at each step, and the profound implications for every living organism on our planet.

From the smallest blade of grass to the mightiest eagle, all life depends on the transfer of energy. The energy pyramid elegantly illustrates this transfer, revealing the hidden dynamics that shape ecosystems and dictate the very structure of food chains. Understanding this pyramid is key to grasping the delicate balance of nature and the impact of human activities on the environment.

The Basics: What is an Energy Pyramid?

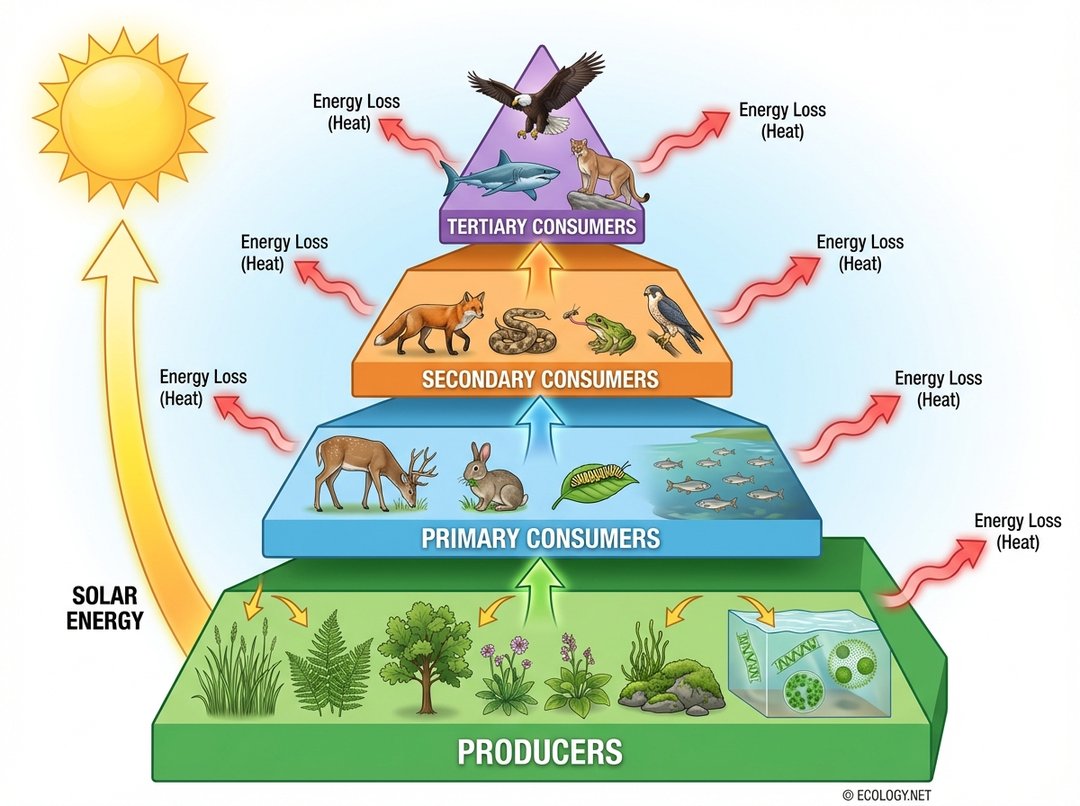

An energy pyramid, also known as a trophic pyramid, is a graphical representation designed to show the biomass or bio productivity at each trophic level in a given ecosystem. It is a foundational concept in ecology, demonstrating how energy is transferred from one organism to another within a food web. The pyramid shape itself is crucial: it signifies that there is significantly more energy at the bottom levels than at the top.

The pyramid is typically divided into distinct horizontal levels, each representing a different trophic level:

- Producers (Autotrophs): Forming the broad base of the pyramid, these organisms create their own food, primarily through photosynthesis. Examples include plants, algae, and some bacteria. They capture energy directly from the sun or chemical reactions, making it available to the rest of the ecosystem.

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These organisms feed directly on producers. Think of deer grazing on grass, rabbits munching on clover, or zooplankton consuming phytoplankton. They occupy the second level of the pyramid.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores or Omnivores): These animals eat primary consumers. A fox hunting a rabbit, a snake preying on a mouse, or a small fish eating zooplankton are all examples of secondary consumers. They form the third level.

- Tertiary Consumers (Top Carnivores or Omnivores): At the apex of the pyramid are organisms that feed on secondary consumers. An eagle catching a snake, a shark eating a larger fish, or even humans consuming various meats can be considered tertiary consumers. Some ecosystems may even have quaternary consumers, but the number of levels is limited.

Energy flows upwards through these levels, starting from the producers and moving towards the top predators. This flow is not a perfect transfer; rather, it is a process accompanied by significant energy loss at each step.

Why is Energy Lost at Each Level? The 10% Rule Explained

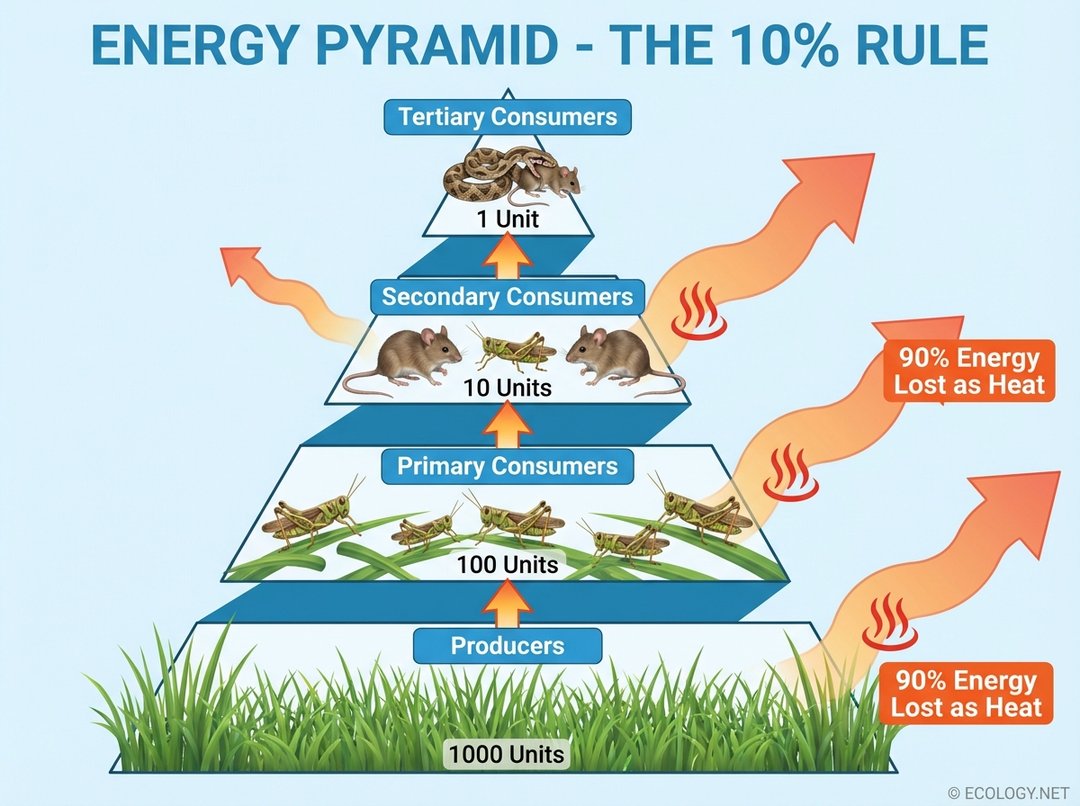

One of the most critical aspects of the energy pyramid is the dramatic reduction in available energy as one moves up the trophic levels. This phenomenon is primarily governed by what ecologists call the “10% rule” or Lindeman’s Rule.

The 10% rule states that, on average, only about 10 percent of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next trophic level. The remaining 90 percent is lost to the environment, primarily as metabolic heat, or is used for life processes such as respiration, movement, and reproduction. A significant portion of energy is also lost because not all biomass from one level is consumed by the next, and not all consumed biomass is fully digested and assimilated.

Consider this example:

- If producers capture 10,000 units of energy from the sun, only about 1,000 units will be available to the primary consumers that eat them.

- From those 1,000 units, only about 100 units will be transferred to the secondary consumers.

- And finally, a mere 10 units will reach the tertiary consumers.

This exponential decrease in energy explains why food chains rarely extend beyond four or five trophic levels. There simply is not enough energy left to support a higher level of consumers. It also highlights why there are always far more producers than primary consumers, and far more primary consumers than secondary consumers, and so on. The base of the pyramid must be vast to support the levels above it.

The Consequences of Energy Loss

The inefficiency of energy transfer has profound consequences for ecosystems:

- Limited Food Chain Length: As mentioned, the rapid decline in energy limits the number of trophic levels. Most ecosystems have a maximum of four or five levels.

- Biomass Distribution: The total biomass (the total mass of organisms) at each trophic level generally mirrors the energy pyramid. There is a much greater biomass of producers than primary consumers, and so on.

- Vulnerability of Top Predators: Organisms at higher trophic levels require a much larger base of prey to sustain themselves. This makes them particularly vulnerable to disturbances at lower levels of the food chain. A decline in producers can have a cascading effect, severely impacting top predators.

Implications and Advanced Concepts

Beyond the fundamental flow of energy, the pyramid structure also helps us understand more complex ecological phenomena, particularly concerning environmental contaminants.

Bioaccumulation & Biomagnification

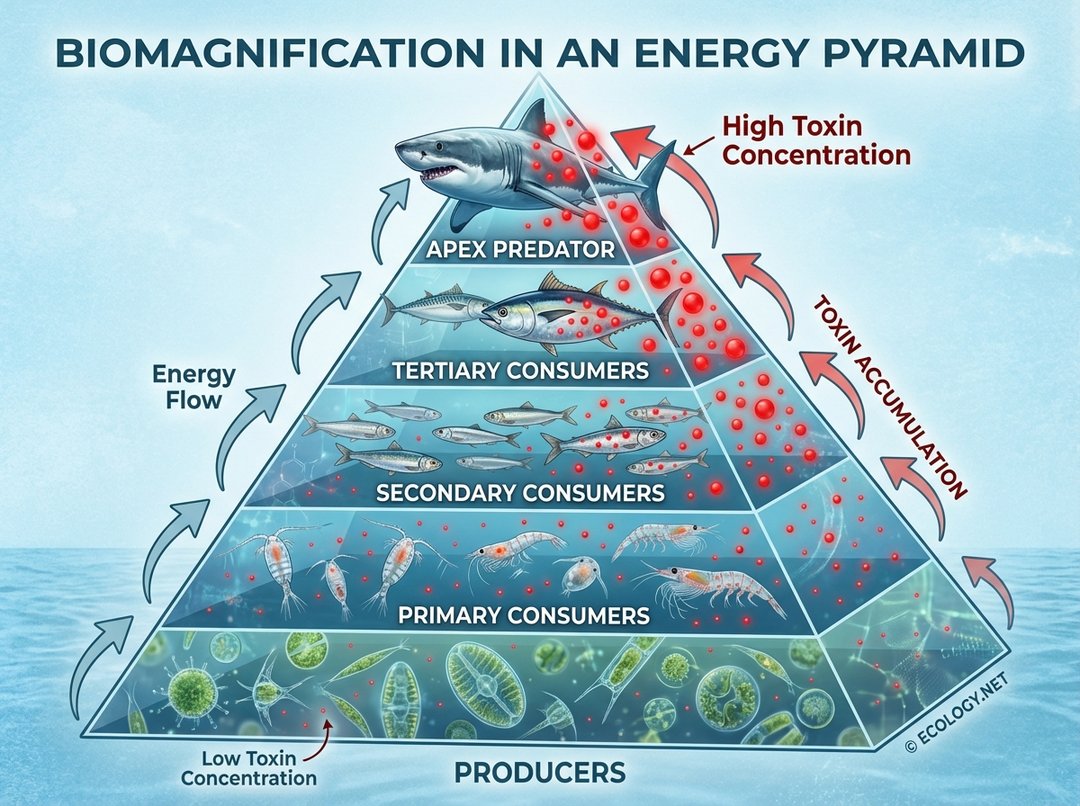

While energy decreases as you move up the pyramid, certain substances, particularly persistent toxins, can do the opposite. This leads to two critical concepts:

- Bioaccumulation: This is the gradual accumulation of substances, such as pesticides or other chemicals, in an organism. It occurs when an organism absorbs a toxic substance at a rate faster than it can excrete or metabolize it. For example, a single fish might accumulate small amounts of mercury over its lifetime.

- Biomagnification (or Bioamplification): This is the increase in concentration of a substance, such as a persistent pollutant, in organisms at successively higher trophic levels of a food chain. When a primary consumer eats many producers, it ingests all the accumulated toxins from those producers. A secondary consumer then eats many primary consumers, accumulating all their toxins, and so on.

The result is that organisms at the top of the food chain can have toxin concentrations many thousands of times higher than those found in the environment or in organisms at the base of the food chain. Classic examples include the biomagnification of DDT in birds of prey, leading to thin eggshells and population declines, or mercury in aquatic food chains, impacting top predators like tuna and sharks, and ultimately humans.

This concept underscores the interconnectedness of ecosystems and the far reaching consequences of pollution, even at seemingly low levels in the environment.

Types of Ecological Pyramids

While the energy pyramid is always upright due to the laws of thermodynamics, it is worth noting that other types of ecological pyramids exist:

- Pyramid of Numbers: Shows the number of individual organisms at each trophic level. This pyramid can sometimes be inverted, for example, if a single large tree (producer) supports many insects (primary consumers).

- Pyramid of Biomass: Represents the total mass of organisms at each trophic level. This pyramid is generally upright, but can be inverted in some aquatic ecosystems where producers (phytoplankton) have a very short lifespan and rapid turnover, meaning their total biomass at any given moment is less than the biomass of the longer lived zooplankton that feed on them.

However, the energy pyramid remains the most fundamental and universally applicable, as it directly reflects the flow of energy, which is the ultimate driver of all life.

Real World Examples and Significance

Understanding energy pyramids is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for conservation, agriculture, and human health.

Examples Across Ecosystems

- Terrestrial Ecosystems: In a grassland, vast quantities of grass (producers) support herds of herbivores like bison or antelope (primary consumers). These, in turn, support a smaller number of predators like wolves or lions (secondary consumers).

- Aquatic Ecosystems: Oceans rely on microscopic phytoplankton (producers) to fuel zooplankton (primary consumers). Small fish eat zooplankton, larger fish eat small fish, and apex predators like sharks or killer whales sit at the top.

Why Energy Pyramids Matter

- Conservation: Protecting top predators requires safeguarding the entire food web below them. If the base of the pyramid is compromised, the entire ecosystem can collapse. Conservation efforts often focus on preserving habitat for producers and primary consumers to ensure the stability of higher trophic levels.

- Human Food Choices: From an energy efficiency standpoint, consuming food from lower trophic levels (e.g., plant based diets) is far more efficient than consuming food from higher trophic levels (e.g., meat). This is because less energy is lost in the transfer. This understanding informs discussions about sustainable agriculture and feeding a growing global population.

- Environmental Monitoring: The health of an ecosystem can often be gauged by the stability and diversity of its trophic levels. Disruptions, such as the decline of a key producer or the overfishing of a primary consumer, can send ripples throughout the entire pyramid.

- Pollution Control: The concept of biomagnification highlights the critical need to control persistent pollutants at their source. Even small amounts of toxins released into the environment can have devastating effects on top predators, including humans, due to their accumulation up the food chain.

Conclusion

The energy pyramid stands as a powerful testament to the fundamental laws governing life on Earth. It visually encapsulates the flow of energy, the inevitable loss at each transfer, and the intricate web of relationships that bind all living things. From the lush forests to the deepest oceans, this ecological principle dictates the structure, stability, and vulnerability of every ecosystem.

By appreciating the energy pyramid, we gain a deeper understanding of our place within the natural world and the far reaching consequences of our actions. It serves as a vital reminder that the health of the planet, and indeed our own well being, is inextricably linked to the delicate balance of energy that sustains all life.