Beneath every step we take, hidden from plain sight, lies a complex and dynamic world vital to all life on Earth: the soil. Far from being a uniform mass, soil is a meticulously organized system, structured into distinct layers that tell a story of its formation, history, and ecological function. This intricate arrangement is known as a soil profile, and understanding it unlocks profound insights into our planet’s ecosystems.

What is a Soil Profile?

A soil profile is essentially a vertical cross-section of the soil, extending from the surface down to the underlying bedrock or parent material. Imagine slicing a cake vertically to see its different layers; a soil profile offers a similar view into the earth. Each distinct layer within this profile is called a horizon, characterized by unique physical, chemical, and biological properties. These horizons develop over vast stretches of time, influenced by a myriad of environmental factors.

Examining a soil profile allows scientists, farmers, and ecologists to understand the soil’s composition, its capacity to support plant life, its water retention capabilities, and its overall health. It is a fundamental concept in soil science, providing a framework for classifying and managing this invaluable natural resource.

The Layered Earth: Understanding Soil Horizons

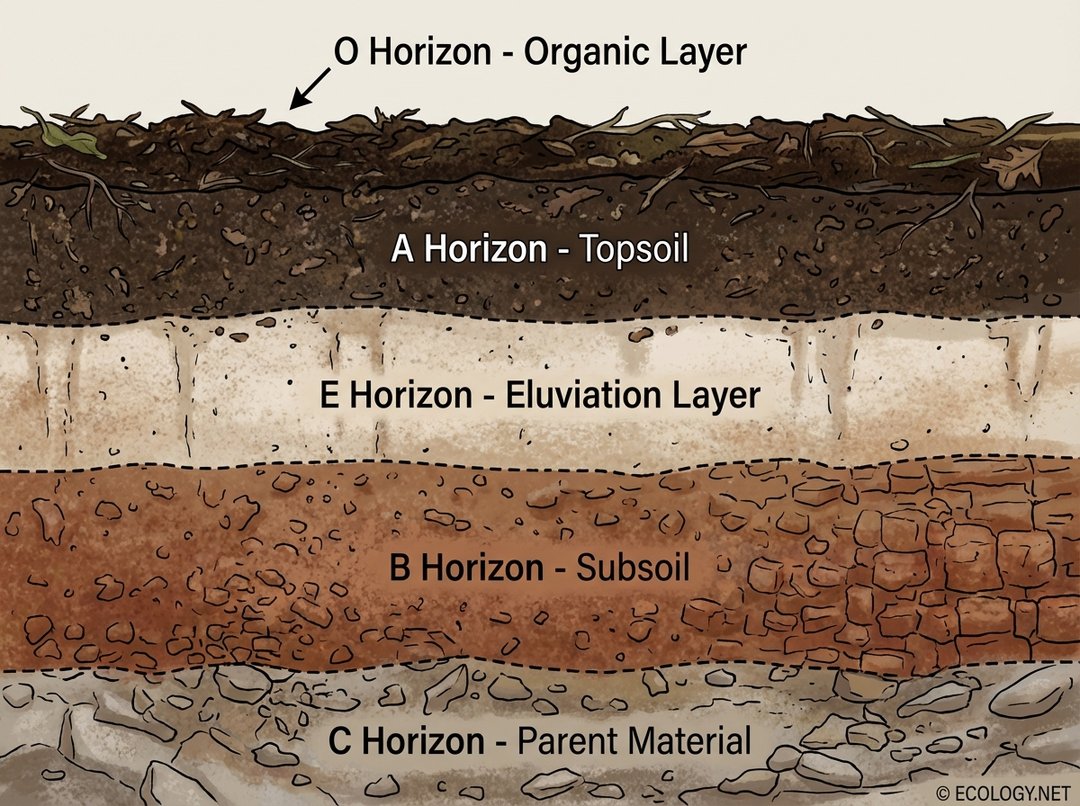

The most striking feature of a soil profile is its stratification into horizons. While the exact number and characteristics of horizons can vary greatly depending on the soil type and environment, several major layers are commonly recognized. These layers are typically designated with capital letters, forming a universal language for soil scientists.

Major Soil Horizons Explained

- O Horizon: The Organic Layer

This is the uppermost layer, primarily composed of organic materials at various stages of decomposition. It is often dark in color and can be quite thick in forested areas, consisting of leaf litter, twigs, moss, and other plant residues. The ‘O’ stands for organic. This layer is crucial for nutrient cycling and provides habitat for countless microorganisms and small invertebrates.

- Oi (Litter Layer): Undecomposed surface litter.

- Oe (Fermentation Layer): Partially decomposed organic material.

- Oa (Humus Layer): Highly decomposed organic matter, often dark and rich.

- A Horizon: The Topsoil

Often referred to as topsoil, the A horizon is typically darker than the layers below it due to the accumulation of decomposed organic matter, known as humus, mixed with mineral particles. It is a zone of intense biological activity, rich in plant roots, earthworms, insects, and microorganisms. This horizon is vital for agriculture, as it is where most plant nutrients are found and absorbed.

- E Horizon: The Eluviation Layer

The ‘E’ stands for eluviation, which means “washing out.” This horizon is characterized by the leaching of minerals and organic matter by downward-moving water. As water percolates through the A horizon, it dissolves and carries away clay, iron, aluminum, and humus, leaving behind a lighter colored layer, often rich in quartz or other resistant minerals. The E horizon is not always present but is common in older, well-developed soils, particularly in forested regions.

- B Horizon: The Subsoil

Also known as the subsoil, the B horizon is where the materials leached from the A and E horizons accumulate. This process is called illuviation, or “washing in.” It often has a distinct color, ranging from reddish to yellowish brown, due to the accumulation of iron oxides, clay minerals, and sometimes humus. The B horizon is generally denser and has less organic matter than the A horizon, but it can still be penetrated by plant roots.

- C Horizon: The Parent Material

This layer consists of partially weathered parent material from which the soil above it developed. It can be bedrock, glacial till, river sediments, or wind-blown deposits. The C horizon shows minimal biological activity and little to no evidence of soil-forming processes like eluviation or illuviation. It serves as the source of mineral particles for the overlying horizons.

- R Horizon: The Bedrock

Below the C horizon lies the R horizon, which is the unweathered, solid bedrock. This layer is not technically part of the soil itself but forms the foundation upon which the C horizon and subsequent soil layers develop. It is the ultimate source of the mineral components of the soil.

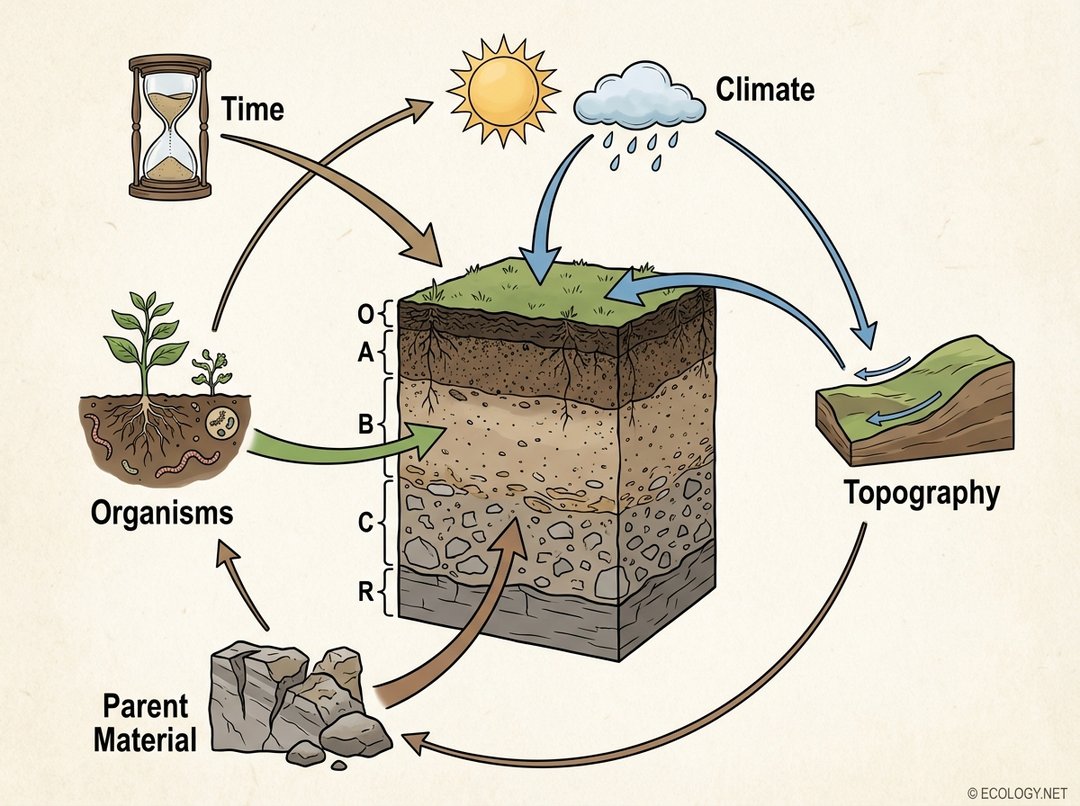

The Architects of Soil: Five Key Forming Factors

The incredible diversity of soil profiles across the globe is not random. It is the result of a complex interplay of five fundamental soil-forming factors. These factors, often remembered by the acronym CLORPT (Climate, Organisms, Relief/Topography, Parent Material, Time), dictate how soil develops and what its profile will look like.

- Parent Material: The Foundation

This refers to the geological material from which the soil forms. It can be bedrock, volcanic ash, glacial deposits, river sediments, or wind-blown sand. The parent material dictates the initial mineral composition, texture, and chemical properties of the soil. For example, soil formed from limestone will be rich in calcium, while soil from granite will be more acidic and contain different minerals.

- Climate: The Driving Force

Climate, particularly temperature and precipitation, is arguably the most influential factor. High rainfall leads to increased leaching and the development of distinct E horizons. Warm, humid climates accelerate chemical weathering and decomposition of organic matter, while cold, dry climates slow these processes. Temperature also affects biological activity and the rate of chemical reactions within the soil.

- Topography (Relief): The Landscape’s Influence

The shape of the land, including its slope, elevation, and aspect (direction it faces), significantly impacts soil development. Steep slopes often experience more erosion, leading to thinner soils, while flatter areas can accumulate deeper, richer soils. Aspect influences temperature and moisture regimes; for instance, south-facing slopes in the Northern Hemisphere receive more direct sunlight and can be drier than north-facing slopes.

- Organisms: The Living Components

Plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms profoundly influence soil formation. Plant roots break up parent material, add organic matter, and extract nutrients. Earthworms and insects mix the soil, create pores, and enhance aeration. Microbes decompose organic matter, cycle nutrients, and contribute to soil structure. The type of vegetation, whether forest, grassland, or desert flora, largely determines the amount and type of organic matter incorporated into the soil.

- Time: The Unfolding Story

Soil formation is a slow process, often taking hundreds to thousands of years to develop distinct horizons. Young soils tend to have less developed profiles, perhaps only an A and C horizon. Over time, as weathering, biological activity, and leaching continue, more complex and differentiated horizons like the E and B layers emerge. The longer a soil has been exposed to the other four factors, the more developed and distinct its profile will be.

From Diagram to Reality: A Glimpse into the Field

While diagrams provide a clear conceptual understanding, seeing a real-world soil profile brings the science to life. When examining a soil pit or a road cut, the distinct layers become tangible, revealing the subtle variations in color, texture, and structure that define each horizon.

In a typical forest setting, one might observe a dark, spongy O horizon at the very top, rich with decomposing leaves and twigs. Below it, the A horizon would appear as a darker, crumbly topsoil, often teeming with fine roots. If an E horizon is present, it might be a lighter gray or whitish band, indicating the leaching of minerals. The B horizon would then reveal itself as a denser, often reddish or yellowish layer, perhaps with visible clay accumulation or distinct structural aggregates. Finally, the C horizon would show the transition to the underlying parent material, with fragments of rock mixed with weathered soil.

The appearance of these horizons can vary dramatically. In a desert environment, the O horizon might be sparse or absent, and the A horizon could be very thin. In a wetland, the soil might be uniformly dark and waterlogged, with unique horizons formed under anaerobic conditions. Each profile is a unique fingerprint of its environment and history.

The Global Tapestry: Variations in Soil Profiles

The world’s soils are incredibly diverse, and their profiles reflect this global tapestry. From the deep, rich Mollisols of grasslands to the highly weathered Oxisols of tropical rainforests, each soil type possesses a characteristic profile. For instance:

- Grassland Soils (Mollisols): Known for their thick, dark A horizons, rich in organic matter due to the extensive root systems of grasses. They often lack a distinct E horizon.

- Forest Soils (Alfisols, Spodosols): Typically feature a prominent O horizon and often a well-developed E horizon due to significant leaching. The B horizon can be rich in clay or iron.

- Desert Soils (Aridisols): Characterized by sparse organic matter, thin A horizons, and often accumulations of salts or calcium carbonate in the B or C horizons due to limited rainfall and high evaporation.

- Tropical Soils (Oxisols, Ultisols): Often deeply weathered with thick B horizons rich in iron and aluminum oxides, giving them a reddish color. They tend to have low fertility once the organic matter is depleted.

These variations are not just academic curiosities; they have profound implications for agriculture, land use planning, and ecosystem management.

Why Soil Profiles Matter: Ecological and Human Significance

Understanding soil profiles is far more than an exercise in classification; it is crucial for managing our planet’s resources and sustaining life. The arrangement of horizons dictates:

- Water Movement and Storage: Different horizons have varying porosities and textures, influencing how water infiltrates, drains, and is retained within the soil. This impacts groundwater recharge, flood control, and plant water availability.

- Nutrient Cycling: The distribution of organic matter and minerals across horizons affects nutrient availability for plants and the overall fertility of the soil. The O and A horizons are typically nutrient powerhouses.

- Habitat for Organisms: Each horizon provides unique microhabitats for a vast array of soil organisms, from bacteria and fungi to insects and burrowing animals, all of which contribute to soil health and ecosystem function.

- Agricultural Productivity: Farmers rely on understanding their soil profiles to make informed decisions about crop selection, fertilization, irrigation, and tillage practices. The depth and quality of the A horizon are particularly critical for crop yields.

- Environmental Management: Soil profiles are essential for assessing soil degradation, pollution, and the impact of human activities. They inform strategies for erosion control, waste disposal, and land reclamation.

- Construction and Engineering: Engineers consider soil profiles when designing foundations for buildings, roads, and other infrastructure, as the stability and bearing capacity of different horizons vary significantly.

Conclusion

The soil profile is a testament to the intricate processes that shape our natural world. It is a dynamic record of geological history, climatic forces, biological activity, and the passage of time. By peeling back the layers of soil, we gain a deeper appreciation for the hidden complexity beneath our feet and the vital role this often-overlooked resource plays in supporting all terrestrial life. From filtering water to growing our food, the health and structure of soil profiles are fundamental to the well-being of both ecosystems and human societies. Protecting and understanding these layered wonders is a critical step towards a sustainable future.