Beneath our feet, a hidden world of intricate layers quietly supports all terrestrial life. This subterranean architecture, often taken for granted, is known as soil horizons. Far from being a uniform mass, soil is a complex, stratified system, each layer telling a story of its formation, composition, and the vital roles it plays in our ecosystem.

Understanding soil horizons is akin to reading the Earth’s autobiography. Each distinct band, differentiated by color, texture, and chemical makeup, reveals the dynamic processes that have shaped it over millennia. From the bustling biological activity of the topsoil to the ancient bedrock below, these layers are fundamental to agriculture, environmental health, and even the stability of our built world.

What are Soil Horizons? The Earth’s Layered Skin

Soil horizons are essentially horizontal layers within the soil profile, each with unique characteristics that distinguish it from the layers above and below. Think of them as geological strata, but formed by a combination of biological, chemical, and physical processes rather than just sedimentation.

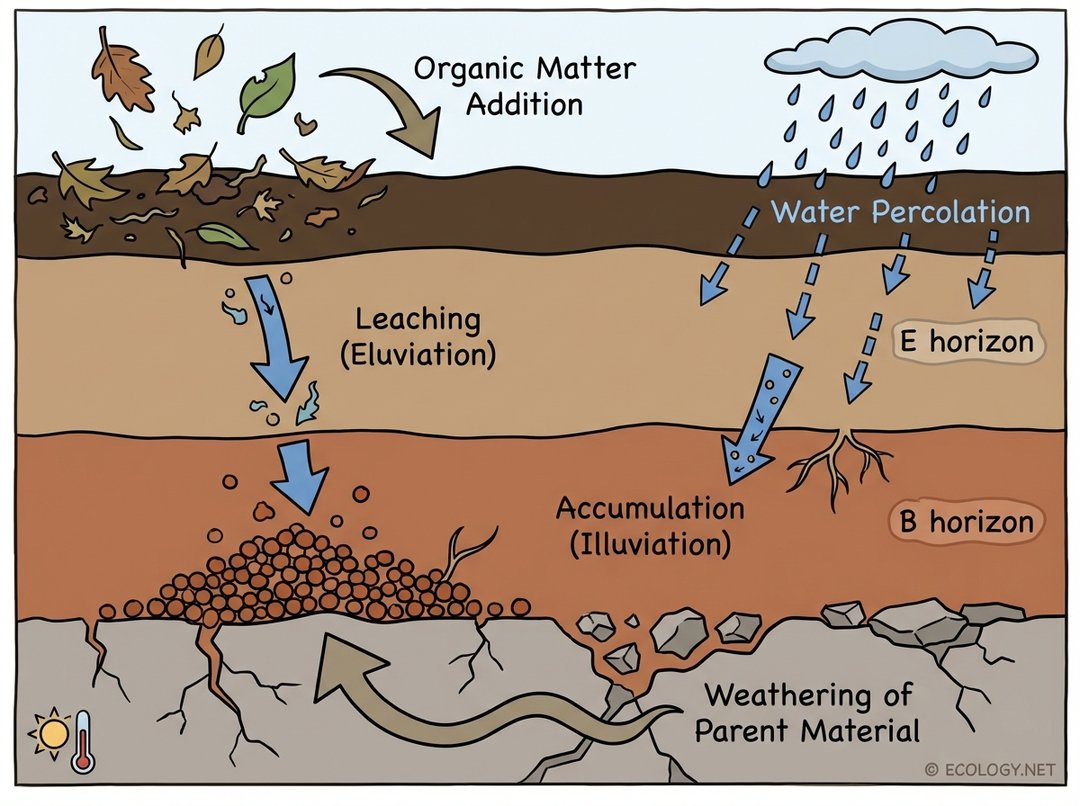

The development of these layers is a slow, continuous dance influenced by several key factors:

- Parent Material: The original rock or sediment from which the soil forms.

- Climate: Temperature and rainfall dictate the speed of weathering, decomposition of organic matter, and the movement of water and dissolved substances.

- Organisms: Plants, animals, and microorganisms contribute organic matter, mix the soil, and facilitate nutrient cycling.

- Relief (Topography): The slope of the land affects water runoff, erosion, and soil depth.

- Time: Soil formation is a gradual process; older soils generally have more distinct and developed horizons.

These factors interact to create a vertical sequence of layers, each contributing to the overall function of the soil. Water percolates downwards, carrying dissolved minerals and fine particles from upper layers to accumulate in lower ones. Organic matter from decaying plants and animals enriches the surface, while weathering slowly breaks down the underlying rock.

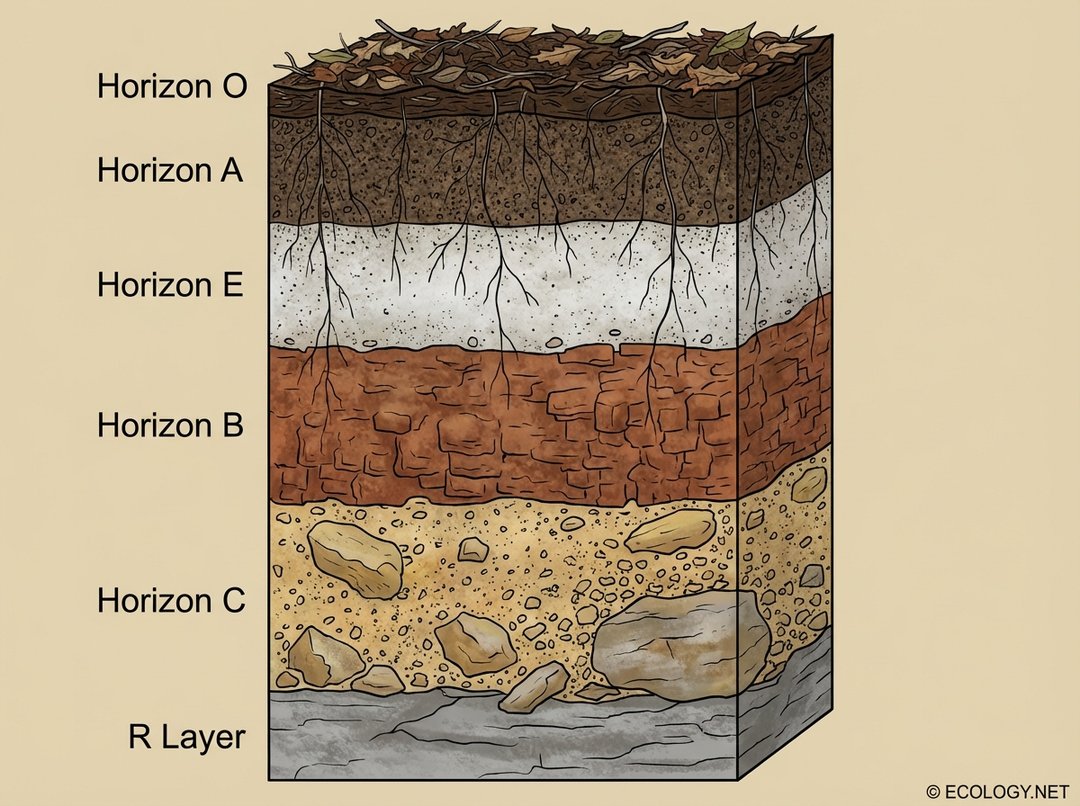

The Master Profile: The Five Major Horizons

While soils vary greatly across different regions, a generalized system of major horizons helps scientists classify and understand them. These are typically designated with capital letters: O, A, E, B, C, and R. Not all soils will have every single horizon, but this sequence represents a complete, well-developed soil profile.

Horizon O: The Organic Layer

This is the uppermost layer, primarily composed of organic materials at various stages of decomposition. It is often found in forested areas, but can also be present in grasslands. The ‘O’ stands for organic.

- Characteristics: Dark brown to black, rich in plant and animal residues such as leaves, twigs, mosses, and humus. It can be further divided into Oi (slightly decomposed), Oe (moderately decomposed), and Oa (highly decomposed).

- Significance: Crucial for nutrient cycling, water retention, and providing energy for soil organisms. It acts like a sponge, absorbing rainfall and slowly releasing it, preventing erosion.

Horizon A: The Topsoil

Often considered the most vital layer for agriculture, Horizon A is a mineral horizon that is rich in decomposed organic matter, giving it a darker color than the layers below. It is the zone where most biological activity occurs.

- Characteristics: Darker brown or black, crumbly texture, abundant roots, earthworms, insects, and microorganisms. It is a mix of organic matter and weathered mineral particles.

- Significance: The primary zone for plant growth, nutrient absorption, and biological activity. Its fertility is paramount for crop production and ecosystem health. This is where the magic of life truly happens in the soil.

Horizon E: The Eluviation Layer

The ‘E’ stands for eluviation, which means “washing out.” This layer is typically lighter in color than the A horizon because water moving downwards has leached out clay, iron, aluminum, and organic matter.

- Characteristics: Often pale gray or whitish, sandy texture, lower in organic matter and nutrients compared to the A horizon. It is more common in older, highly weathered soils, particularly in forest environments.

- Significance: A zone of maximum leaching, indicating significant downward movement of water and dissolved substances.

Horizon B: The Subsoil (Accumulation Layer)

This horizon is often called the subsoil and is characterized by the accumulation of materials leached from the horizons above. The ‘B’ stands for illuviation, meaning “washing in.”

- Characteristics: Often reddish, yellowish, or brownish due to the accumulation of clay, iron oxides, aluminum hydroxides, and sometimes organic matter. It is generally denser and has a blockier or prismatic structure compared to the A horizon.

- Significance: Stores water and nutrients that have moved down from the topsoil. It can be a significant reservoir for plant roots, especially during dry periods.

Horizon C: The Parent Material

The C horizon consists of partially weathered parent material. It is the least affected by biological activity and the processes that form the O, A, E, and B horizons.

- Characteristics: Light brown or yellowish, composed of weathered rock fragments, gravel, and unconsolidated sediments. It has little to no organic matter.

- Significance: Represents the raw material from which the upper horizons are formed. It provides the mineral base and influences the texture and chemical properties of the overlying soil.

R Layer: The Bedrock

The ‘R’ layer stands for Regolith or Rock. This is the unweathered, solid bedrock that lies beneath the soil profile.

- Characteristics: Solid rock, such as granite, limestone, or sandstone.

- Significance: The ultimate source of the parent material for the soil above, though it may take thousands to millions of years for it to weather and contribute to soil formation.

Why Do Soil Horizons Matter? Practical Insights

Understanding soil horizons is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound practical implications across various fields.

For Agriculture and Food Security

Farmers rely heavily on the health of the A horizon for crop productivity. Its depth, organic matter content, and nutrient levels directly influence yield. The B horizon’s ability to store water and nutrients is also critical, especially in drought-prone areas. Knowledge of horizons helps in:

- Fertilizer application: Tailoring nutrient inputs to specific soil layers.

- Irrigation management: Understanding water infiltration and retention.

- Tillage practices: Minimizing disturbance to the fragile topsoil.

- Crop selection: Choosing plants best suited to the soil’s characteristics.

For Environmental Health

Soil horizons are integral to ecosystem services that benefit all life:

- Water filtration: Different layers filter pollutants and regulate water flow into groundwater systems.

- Carbon sequestration: The O and A horizons are major carbon sinks, playing a crucial role in mitigating climate change.

- Biodiversity: Each horizon provides unique habitats for a vast array of organisms, from microbes to burrowing animals.

- Waste decomposition: Soil organisms break down organic waste, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem.

For Construction and Engineering

Engineers and builders must consider soil horizons when designing foundations for buildings, roads, and other infrastructure. The bearing capacity, stability, and drainage properties vary significantly between layers, impacting construction costs and safety.

Factors Influencing Horizon Development: A Deeper Dive

While the basic definitions provide a framework, the specific characteristics and thickness of horizons are highly variable, shaped by a dynamic interplay of environmental factors over long periods.

Climate’s Dominant Role

Climate is arguably the most influential factor. In humid climates, high rainfall leads to intense leaching, often resulting in pronounced E horizons and significant accumulation in the B horizon. In arid regions, water movement is upward due to evaporation, leading to salt accumulation near the surface. Temperature affects the rate of chemical reactions and organic matter decomposition; warmer climates generally have faster decomposition and less organic matter accumulation in the O horizon, while colder climates can lead to thick, peaty O horizons.

The Living Influence of Organisms

From microscopic bacteria to large burrowing mammals, organisms are constant architects of soil. Plant roots penetrate deep, extracting nutrients and water, while their decaying leaves and stems form the O horizon. Earthworms and insects mix soil particles, create channels for air and water, and incorporate organic matter into the A horizon. Fungi and bacteria are the primary decomposers, transforming raw organic material into stable humus.

Relief and the Landscape

The shape of the land, or topography, dictates how water moves across and through the soil. On steep slopes, erosion can strip away the O and A horizons, leaving thinner, less developed soils. In depressions, water accumulates, leading to thicker, often waterlogged horizons. Aspect, the direction a slope faces, also influences soil temperature and moisture, affecting vegetation and decomposition rates.

Parent Material’s Legacy

The type of rock or sediment from which the soil originates imparts its initial characteristics. Granite, for example, weathers into sandy soils, while basalt forms clay-rich soils. The mineral composition of the parent material determines the initial nutrient content and influences the soil’s pH and fertility. For instance, soils derived from limestone tend to be more alkaline.

The Unfolding of Time

Soil formation is a testament to patience. Young soils, like those on recent volcanic deposits or floodplains, may only have rudimentary A and C horizons. Over thousands to millions of years, as weathering continues, organic matter accumulates, and materials are translocated, the full suite of O, E, and B horizons can develop, becoming more distinct and complex. Time allows for the full expression of all other soil-forming factors.

Variations and Beyond the Basics

While the O, A, E, B, C, R system is a powerful generalization, real-world soils exhibit immense diversity. Soil scientists recognize numerous sub-horizons and specific horizon designations to capture this complexity. For example, a B horizon might be further classified as Bt (accumulation of clay), Bs (accumulation of iron and aluminum oxides), or Bk (accumulation of carbonates).

Different soil orders, the broadest classification of soils, are defined by their unique horizon sequences and characteristics. Mollisols, common in grasslands, are known for their thick, dark A horizons. Spodosols, often found in coniferous forests, feature a prominent E horizon and a distinct Bs horizon. Oxisols, prevalent in tropical regions, are highly weathered and often lack distinct O and A horizons, instead having deep, reddish B horizons.

The boundaries between horizons can be sharp and abrupt, or they can be gradual and diffuse, blending imperceptibly into one another. This variability reflects the specific combination of soil-forming factors at any given location. Soil horizons are not merely static layers, but dynamic interfaces where geological, biological, and climatic forces constantly interact and reshape the Earth’s living skin.

Conclusion: A Deeper Appreciation for the Ground Beneath Us

The intricate world of soil horizons offers a profound glimpse into the Earth’s natural processes. From the bustling life of the organic rich topsoil to the ancient bedrock that anchors it all, each layer plays a critical role in sustaining life on our planet. These hidden strata are not just dirt; they are the foundation of our ecosystems, the engine of our agriculture, and a vital component of our global climate system.

By understanding the formation, characteristics, and significance of soil horizons, we gain a deeper appreciation for the ground beneath our feet. This knowledge empowers us to make more informed decisions about land use, conservation, and sustainable practices, ensuring the health and productivity of our soils for generations to come. The next time you walk across a field or through a forest, remember the complex, living layers beneath you, silently working to support the world above.