Beneath our feet lies a world teeming with life and history, a foundation for nearly all terrestrial ecosystems: soil. Far from being mere dirt, soil is a complex, living entity, constantly evolving through a fascinating process known as soil formation. Understanding how soil comes to be is not just a scientific curiosity; it is key to appreciating the delicate balance of our planet, the food we eat, and the health of our environment.

Soil formation is a slow, intricate dance between geological forces, biological activity, and atmospheric conditions, unfolding over millennia. It transforms barren rock into fertile ground, creating the very medium that sustains plant life and, by extension, all life on land. Let us embark on a journey to uncover the secrets of this vital process, from the fundamental building blocks to the intricate layers that tell a story of time and transformation.

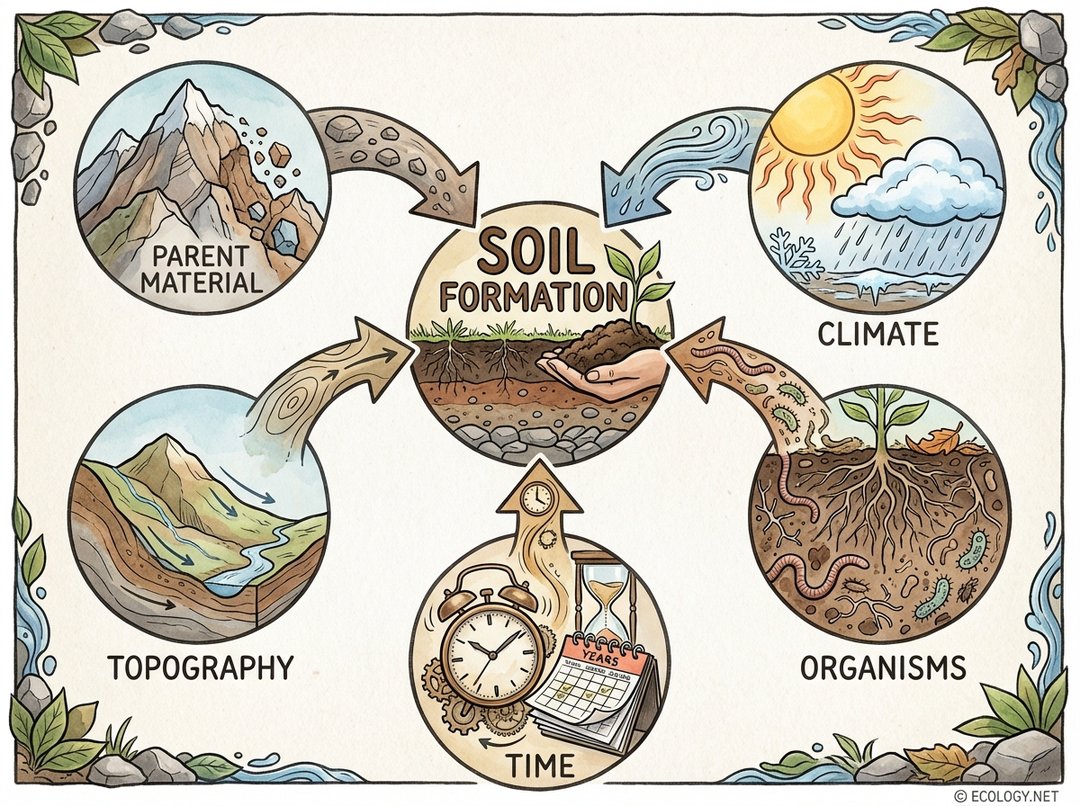

The Five Factors of Soil Formation

At the heart of soil formation lies the interplay of five fundamental factors. These are not isolated elements but rather a dynamic quintet, each influencing and being influenced by the others. Imagine them as the master sculptors, shaping the character and composition of every soil type across the globe.

Let us explore each of these crucial factors:

- Parent Material: The Starting Block

This refers to the geological material from which soil develops. It could be bedrock, such as granite or limestone, or unconsolidated sediments like glacial till, river alluvium, or wind-blown loess. The parent material dictates the initial mineral composition of the soil. For instance, soil formed from granite will be rich in quartz and feldspar, while soil from limestone will have a higher calcium content. This initial chemical signature profoundly influences the soil’s fertility, texture, and pH. - Climate: The Master Driver

Climate is arguably the most influential factor. Temperature and precipitation directly impact the rates of weathering, decomposition of organic matter, and movement of water through the soil profile.- In hot, humid climates, chemical weathering is rapid, leading to deeply weathered soils often rich in iron and aluminum oxides, like the red soils of tropical rainforests.

- In cold, dry climates, physical weathering dominates, and decomposition is slow, resulting in thinner soils with less organic matter.

- Moderate climates, with distinct seasons, foster a balance of processes, often leading to highly productive agricultural soils.

- Topography: The Landscape’s Influence

The shape of the land, its slope, aspect (direction it faces), and elevation, significantly affects soil formation.- On steep slopes, soil tends to be thinner due to erosion and runoff, which carry away weathered material.

- In flatter areas, water can accumulate, leading to deeper soils and potentially waterlogged conditions.

- Aspect influences temperature and moisture regimes; a south-facing slope in the Northern Hemisphere receives more direct sunlight, leading to warmer, drier soil than a north-facing slope.

- Organisms: The Living Architects

From microscopic bacteria and fungi to earthworms, insects, and larger animals, organisms play an indispensable role.- Plants contribute organic matter through decaying leaves and roots, forming humus, which improves soil structure and fertility. Their roots also physically break down rock.

- Microbes decompose organic matter, releasing nutrients and creating complex soil compounds.

- Earthworms and burrowing animals mix the soil, create channels for air and water, and bring deeper material to the surface.

- The type of vegetation (e.g., forest versus grassland) also dictates the amount and type of organic matter input, influencing soil acidity and nutrient cycling.

- Time: The Unseen Sculptor

Soil formation is a process that unfolds over vast spans of time, often thousands to tens of thousands of years. Young soils, like those found on recent volcanic deposits or floodplains, are often thin and closely resemble their parent material. As time progresses, the other four factors have more opportunity to act, leading to the development of distinct soil horizons, deeper profiles, and more complex chemical and physical properties. A mature soil is a testament to millennia of continuous transformation.

Weathering: Breaking Down the Foundation

Before soil can truly form, the parent material must first be broken down into smaller particles. This crucial initial step is called weathering, and it occurs through two primary mechanisms: physical and chemical.

Physical Weathering: The Mechanical Breakdown

Physical weathering involves the mechanical disintegration of rocks into smaller fragments without changing their chemical composition. Think of it as breaking a large rock into pebbles and sand.

- Freeze-thaw: In regions with fluctuating temperatures around freezing point, water seeps into cracks in rocks. When it freezes, the water expands by about 9%, exerting immense pressure that widens the cracks. Repeated freezing and thawing can eventually split rocks apart. This is a common sight in mountainous and temperate regions.

- Root Wedging: The relentless power of plant life is also a significant physical weathering agent. As tree roots grow, they can penetrate tiny fissures in rocks. With continued growth, these roots expand, exerting pressure that can pry apart even large boulders.

- Abrasion: The grinding and wearing away of rock surfaces by the friction and impact of particles carried by wind, water, or ice. Imagine river stones becoming smooth over time due to constant tumbling.

- Exfoliation (Onion-Skin Weathering): In areas with large temperature swings, the outer layers of rock expand and contract more than the inner layers, causing them to peel off in sheets, much like the layers of an onion.

Chemical Weathering: The Molecular Transformation

Chemical weathering involves the alteration of the chemical composition of rocks, transforming minerals into new substances. This process is often facilitated by water and atmospheric gases.

- Dissolution: Some minerals, like halite (rock salt) or gypsum, can dissolve directly in water. Even less soluble minerals, such as calcite in limestone, can dissolve in slightly acidic water (like rainwater, which absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to form carbonic acid), leading to the formation of caves and karst landscapes.

- Oxidation: This is a reaction where minerals combine with oxygen, often in the presence of water. A common example is the rusting of iron-bearing minerals, which gives many soils and rocks their characteristic reddish or yellowish hues. For instance, the mineral pyrite (iron sulfide) can oxidize to form iron oxides and sulfuric acid.

- Hydrolysis: The reaction of water with minerals to form new minerals. For example, feldspar, a common mineral in granite, can react with water to form clay minerals, which are crucial components of soil.

- Carbonation: The reaction of minerals with carbonic acid (formed when carbon dioxide dissolves in water). This is particularly effective in weathering carbonate rocks like limestone.

Both physical and chemical weathering often work in tandem. Physical weathering creates more surface area for chemical reactions to occur, accelerating the overall breakdown of parent material.

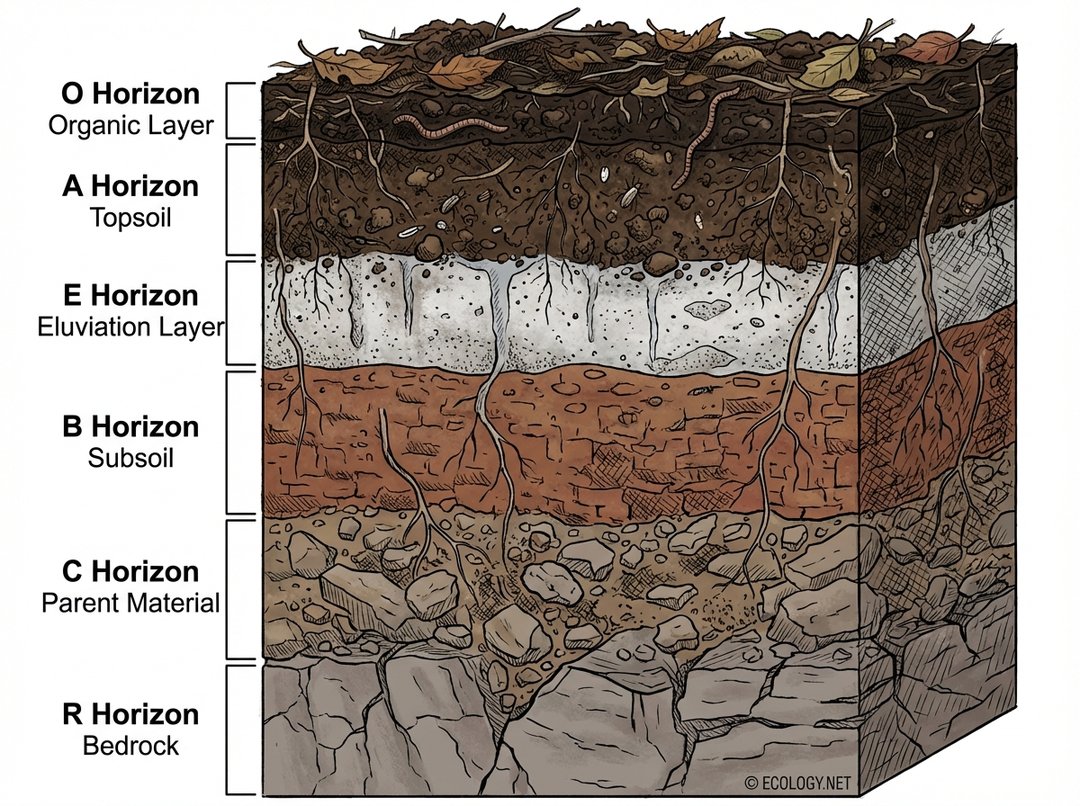

The Soil Profile: Layers of History

As weathering progresses and the other soil-forming factors exert their influence over time, soil begins to differentiate into distinct horizontal layers known as horizons. Collectively, these horizons form the soil profile, a vertical cross-section that tells the story of the soil’s development and history.

Each horizon has unique characteristics in terms of color, texture, structure, and chemical composition. Let us delve into these fascinating layers from top to bottom:

- O Horizon (Organic Layer): This uppermost layer is dominated by organic material. It consists of fresh or partially decomposed plant and animal residues, such as leaves, twigs, and moss. It is dark brown to black and is crucial for nutrient cycling and water retention. In forests, this layer can be quite thick, while in grasslands, it might be thinner and more integrated with the mineral soil below.

- A Horizon (Topsoil): Often referred to as topsoil, this is typically the darkest mineral horizon due to the accumulation of decomposed organic matter (humus) mixed with mineral particles. It is usually rich in nutrients and is where most biological activity, including root growth, occurs. This is the most productive layer for agriculture.

- E Horizon (Eluviation Layer): Not present in all soils, the E horizon is typically lighter in color than the A horizon. It is characterized by eluviation, the process where water moving downwards leaches (washes out) minerals like clay, iron, and aluminum, as well as organic matter. This leaves behind a concentration of resistant minerals, often quartz, giving it a bleached or grayish appearance.

- B Horizon (Subsoil): Also known as the subsoil, this layer is where materials leached from the A and E horizons accumulate. This process is called illuviation. The B horizon often has a reddish-brown color due to the accumulation of iron and aluminum oxides, and it can be denser and have a higher clay content than the horizons above. It is a zone of significant chemical and physical alteration.

- C Horizon (Parent Material): This layer consists of partially weathered parent material. It is less affected by biological activity and soil-forming processes than the horizons above. It can be unconsolidated sediment or fractured bedrock, and its characteristics are still very similar to the original parent material.

- R Horizon (Bedrock): The R horizon represents the unweathered, consolidated bedrock beneath the soil profile. It is the ultimate source of the parent material for the overlying soil layers.

The Dynamic Nature of Soil Formation: Beyond the Basics

While the five factors and distinct horizons provide a framework, soil formation is a continuous and highly dynamic process involving complex interactions and specific soil-forming processes. These processes lead to the incredible diversity of soils found across the planet.

Key Soil-Forming Processes:

- Humification: The decomposition of raw organic matter into stable humus, a dark, amorphous substance that is resistant to further decay. Humus is vital for soil fertility, structure, and water retention.

- Eluviation and Illuviation: As discussed with the E and B horizons, these are the downward (eluviation) and upward (illuviation) movements and accumulation of dissolved or suspended materials within the soil profile.

- Leaching: The removal of soluble materials from the soil by percolating water. This can lead to nutrient loss in some soils but is also part of the differentiation of horizons.

- Calcification: The accumulation of calcium carbonate in a specific horizon, often in drier climates where evaporation exceeds precipitation, drawing calcium upwards in the soil solution.

- Salinization: The accumulation of soluble salts in the soil, typically in arid and semi-arid regions where high evaporation rates leave salts behind on the surface or in shallow horizons.

- Gleyzation: Occurs in waterlogged conditions where oxygen is scarce. Iron is reduced, giving the soil a characteristic bluish-gray or mottled appearance. This process is common in wetlands and poorly drained areas.

These processes, driven by the five factors, create a vast array of soil types, each with unique properties. Soil scientists classify these soils into various orders, suborders, and groups, reflecting their dominant characteristics and the processes that formed them. For example, a soil formed under coniferous forest in a cool, humid climate might develop into a Spodosol, characterized by a distinct E horizon and an accumulation of organic matter and aluminum/iron oxides in the B horizon. Conversely, a soil in a hot, wet tropical region might become an Oxisol, deeply weathered and rich in iron and aluminum oxides.

The study of soil formation, known as pedogenesis, is a testament to the intricate workings of nature. It reveals how seemingly inert rock can be transformed over vast timescales into the living skin of our planet, a medium that supports an astonishing diversity of life.

Conclusion: The Living Earth Beneath Our Feet

Soil formation is a profound and continuous natural phenomenon, a testament to the Earth’s dynamic systems. It is not a static endpoint but an ongoing journey, constantly shaped by the relentless forces of parent material, climate, topography, organisms, and time. From the initial breakdown of bedrock through weathering to the intricate layering of horizons, every step in this process is vital for creating the fertile ground that sustains us.

The next time you walk across a field, hike a mountain trail, or even tend to a garden, take a moment to consider the incredible history beneath your feet. The soil is a living archive, a complex ecosystem, and an indispensable resource. Understanding its formation fosters a deeper appreciation for its value and underscores the importance of its careful stewardship for future generations.