Imagine a vast, sun-drenched landscape stretching to the horizon, dotted with acacia trees and teeming with magnificent wildlife. This iconic image often conjures the savanna, a biome that captivates with its dramatic beauty and incredible ecological dynamism. Far from being a mere transition zone, savannas are vibrant ecosystems, shaped by unique climatic conditions and natural forces, supporting an astonishing array of life.

What is a Savanna? Defining the Golden Grasslands

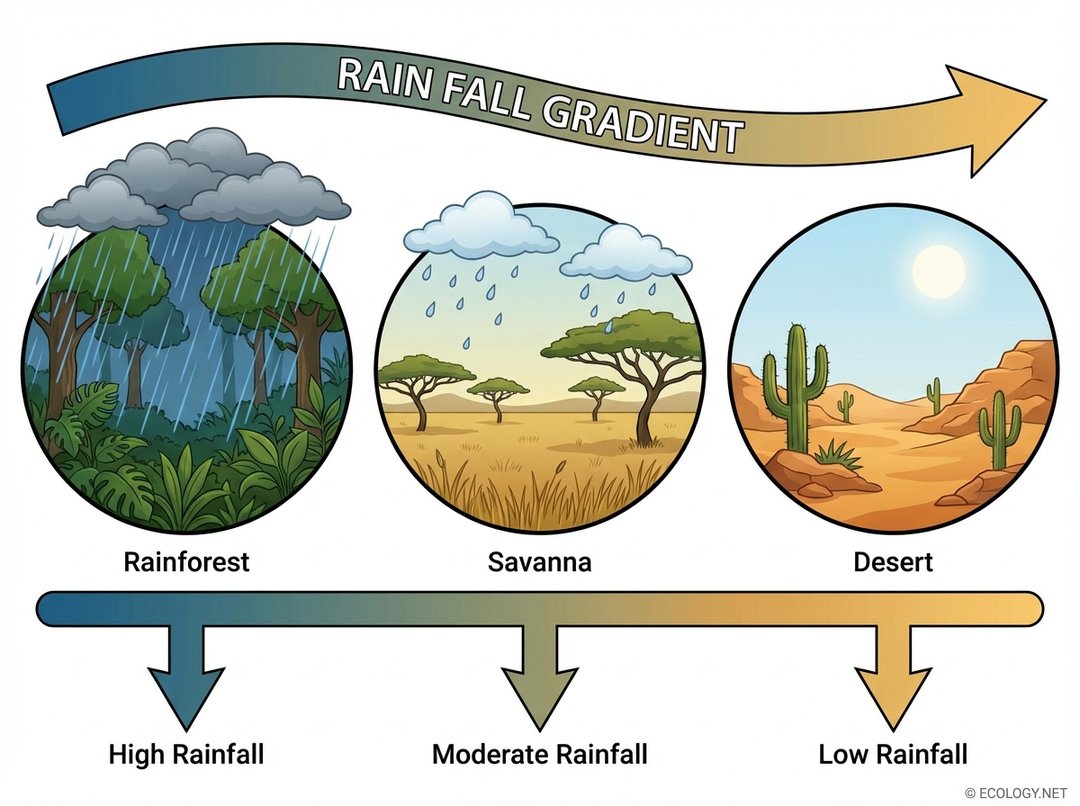

At its core, a savanna is a grassland ecosystem characterized by scattered trees and shrubs, existing in regions with distinct wet and dry seasons. The defining feature that sets savannas apart from dense forests or barren deserts is their moderate rainfall.

To truly understand a savanna, consider its position on the global rainfall spectrum. Rainforests, with their towering canopies, thrive in areas receiving over 2000 millimeters of rain annually. Deserts, conversely, receive less than 250 millimeters, supporting only sparse, specialized vegetation. Savannas occupy the crucial middle ground, typically receiving between 500 and 1500 millimeters of rainfall per year. This specific range is too little to support a continuous forest canopy, yet enough to sustain a rich growth of grasses and scattered woody plants.

This unique rainfall pattern dictates the savanna’s structure. During the wet season, the landscape bursts with lush green grasses, providing abundant forage. The dry season, however, brings a period of dormancy, where grasses turn golden and water becomes scarce, posing significant challenges for its inhabitants. This seasonal rhythm is fundamental to the savanna’s ecological processes.

Global Distribution: More Than Just Africa

While the African savanna is perhaps the most famous, these ecosystems are found on every continent except Antarctica. They are prominent in:

- Africa: Vast expanses across East, Central, and Southern Africa.

- South America: Known as the Cerrado in Brazil and the Llanos in Venezuela and Colombia.

- Australia: Covering significant portions of the northern tropics.

- Asia: Found in parts of India and Southeast Asia.

- North America: Historically, some areas of the Great Plains exhibited savanna-like characteristics.

Each region boasts its own unique flora and fauna, adapted to the specific local conditions, yet all share the fundamental characteristics of a grassland with scattered trees.

The Dynamic Duo: Fire and Grazers, Architects of the Savanna

The savanna is not a static landscape. Its very existence is a testament to the powerful interplay of two natural forces: fire and large grazing animals. These elements are not destructive anomalies; they are integral to maintaining the savanna’s open structure and biodiversity.

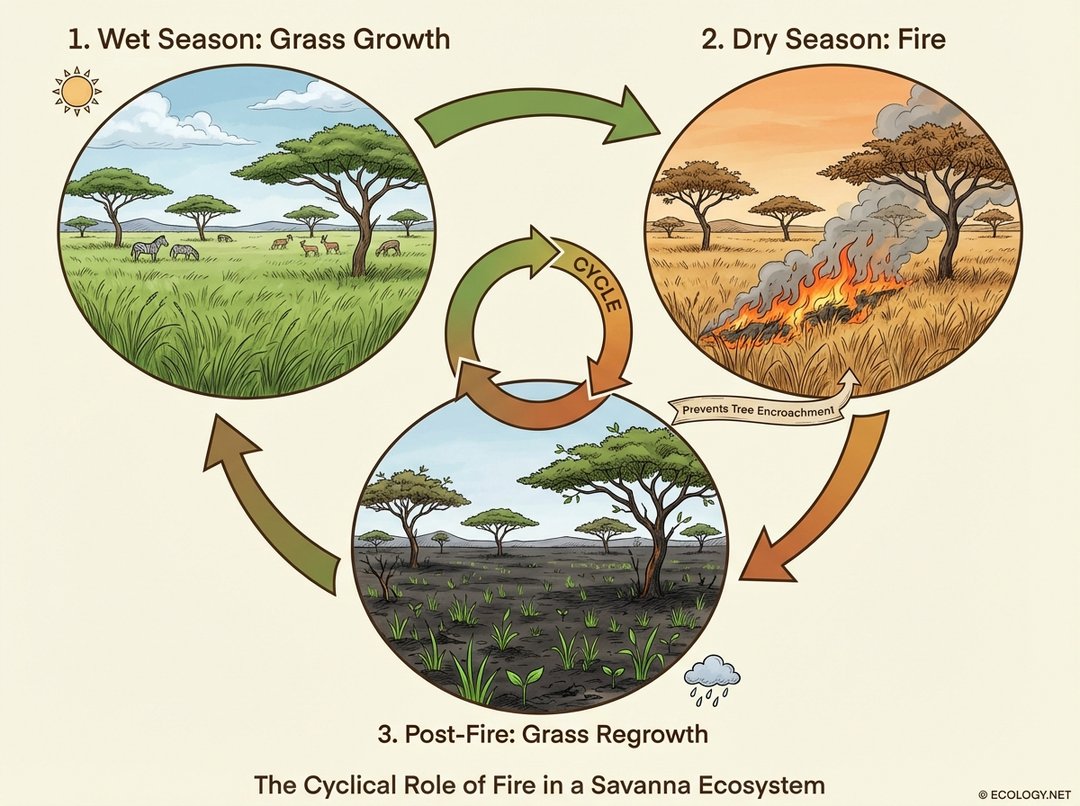

Fire’s Crucial Role: Preventing Forest Encroachment

During the long dry season, the abundant grasses of the savanna become highly flammable. Natural fires, often ignited by lightning, sweep across the landscape. While seemingly destructive, these fires are vital for the savanna’s health. They perform several critical functions:

- Nutrient Cycling: Fires rapidly return nutrients from dead plant material to the soil, fertilizing new growth.

- Controlling Woody Vegetation: Frequent fires prevent tree seedlings from establishing and growing into a dense forest. They selectively burn back young trees, favoring fire-resistant grasses and mature, thick-barked trees like acacias, which can withstand the heat. This process maintains the characteristic open, grassy structure of the savanna.

- Stimulating New Growth: Many savanna grasses and plants have evolved to quickly resprout after a fire, often producing more nutritious shoots that attract grazers.

Without fire, many savannas would gradually transform into woodlands or forests, losing their unique biodiversity and ecological functions. It is a natural process, often misunderstood, that is essential for the savanna’s long-term survival.

The Grazing Pressure: A Constant Shaping Force

Large herbivores, such as wildebeest, zebras, elephants, and kangaroos, are equally important architects of the savanna. Their constant grazing pressure:

- Maintains Grass Height: By consuming vast quantities of grass, grazers prevent the accumulation of excessive fuel, which can lead to more intense, damaging fires.

- Promotes Diversity: Different species of grazers prefer different types of grasses and plants, creating a mosaic of vegetation heights and compositions. This selective grazing can prevent a single plant species from dominating.

- Disperses Seeds: Many plant seeds pass through the digestive systems of herbivores, being dispersed across the landscape in their dung, often with a ready supply of fertilizer.

The co-evolution of savanna plants and animals with fire and grazing has resulted in a highly resilient and productive ecosystem.

Life in the Golden Grasslands: A Tapestry of Biodiversity

The savanna is renowned for its incredible biodiversity, particularly its spectacular megafauna. The open landscape, with its abundant grasses and scattered trees, provides a unique habitat that supports a complex food web.

Herbivores, Predators, and the Dance of Survival

The African savanna, in particular, is home to some of the world’s most iconic animals. Vast herds of herbivores, such as wildebeest, zebras, gazelles, and buffalo, graze on the abundant grasses. These animals often migrate in search of fresh pastures, following the seasonal rains.

This rich supply of prey, in turn, supports a formidable array of predators. Lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and wild dogs are all integral parts of the savanna ecosystem, playing crucial roles in regulating herbivore populations and maintaining ecological balance. The constant interplay between predator and prey is a dramatic and essential aspect of savanna life, driving natural selection and ensuring the health of both populations.

Beyond the Megafauna: A World of Adaptations

While large animals often steal the spotlight, savannas are also home to countless smaller creatures, from diverse bird species and reptiles to insects and amphibians. Each organism has developed remarkable adaptations to survive the challenging savanna environment:

- Plants: Many savanna grasses have deep root systems to access water during dry spells and grow quickly after fires. Trees like the acacia have small leaves to reduce water loss and thorns to deter grazers.

- Animals:

- Migration: Many herbivores undertake long migrations to find water and food.

- Burrowing: Smaller animals often burrow underground to escape the heat and predators.

- Camouflage: The striped patterns of zebras and the spotted coats of big cats provide excellent camouflage in the dappled light and tall grasses.

- Water Conservation: Many animals have physiological adaptations to conserve water.

Types of Savannas: A Diverse Global Landscape

While sharing core characteristics, savannas exhibit variations based on climate, soil, and human influence. Ecologists often categorize them into several types:

- Tropical and Subtropical Savannas: These are the most widespread, found in warm climates with distinct wet and dry seasons. The African savanna, the Brazilian Cerrado, and the Australian tropical savannas fall into this category. They are characterized by tall grasses and scattered broadleaf trees.

- Temperate Savannas: Less common, these occur in regions with more moderate temperatures and distinct seasons, including cold winters. Examples can be found in parts of North and South America, often transitioning into temperate grasslands.

- Mediterranean Savannas: Found in regions with Mediterranean climates, characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters. These often feature evergreen oaks and other drought-resistant trees.

- Flooded Savannas: These savannas experience seasonal flooding, creating unique wetland ecosystems. The Pantanal in South America is a prime example, supporting an incredible diversity of aquatic and terrestrial life.

- Montane Savannas: Found at higher altitudes, these savannas are influenced by mountain climates and topography.

Understanding these distinctions highlights the adaptability of the savanna biome to various environmental conditions.

Ecological Importance and Conservation Challenges

Savannas are not just beautiful landscapes; they provide essential ecosystem services that benefit both wildlife and humanity.

- Biodiversity Hotspots: They harbor an immense diversity of plant and animal species, many of which are found nowhere else.

- Carbon Sequestration: The vast grasslands and scattered trees play a role in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

- Water Regulation: Savanna ecosystems influence regional water cycles, affecting rainfall patterns and water availability.

- Economic Value: They support pastoralism and ecotourism, providing livelihoods for millions of people.

Threats to Savanna Ecosystems

Despite their resilience, savannas face significant threats in the modern era:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Conversion of savannas for agriculture, cattle ranching, and human settlements is a primary driver of habitat destruction.

- Climate Change: Altered rainfall patterns, increased temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events can disrupt the delicate balance of savanna ecosystems.

- Altered Fire Regimes: Suppression of natural fires or, conversely, an increase in human-caused fires can disrupt the natural cycle that maintains savanna structure.

- Poaching: Illegal hunting continues to threaten iconic savanna species, particularly large mammals.

- Invasive Species: Non-native plants and animals can outcompete native species and alter ecosystem processes.

Conservation Efforts

Protecting savannas requires a multi-faceted approach, combining scientific research, community engagement, and policy implementation. Efforts include:

- Establishing and expanding protected areas and national parks.

- Promoting sustainable land management practices that integrate conservation with local livelihoods.

- Restoring degraded savanna landscapes.

- Implementing controlled burning programs to mimic natural fire regimes.

- Combating poaching and illegal wildlife trade.

Conclusion: The Enduring Spirit of the Savanna

The savanna is a biome of extraordinary beauty, resilience, and ecological complexity. It is a testament to how life adapts and thrives under specific environmental pressures, creating a landscape that is both harsh and incredibly bountiful. From the rhythmic dance of fire and grazers to the epic migrations of its wildlife, savannas offer invaluable lessons in ecological balance and interconnectedness.

Understanding and appreciating these golden grasslands is more crucial than ever. By recognizing their vital role in global biodiversity and climate regulation, we can work towards ensuring that the enduring spirit of the savanna continues to inspire and sustain life for generations to come.