Tropical rainforests are often described as the jewels of our planet, vibrant ecosystems teeming with an astonishing array of life. These magnificent natural wonders are far more than just dense collections of trees; they are intricate, dynamic systems that play a crucial role in global climate regulation, biodiversity, and even the discovery of new medicines. Understanding rainforests means delving into a world of constant warmth, abundant moisture, and unparalleled biological complexity.

Located primarily near the equator, rainforests receive copious amounts of rainfall throughout the year, coupled with consistently high temperatures. These ideal conditions foster an explosion of life, creating habitats for millions of species, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth. From towering trees that pierce the sky to the smallest insects hidden in the leaf litter, every organism contributes to the delicate balance of these vital ecosystems.

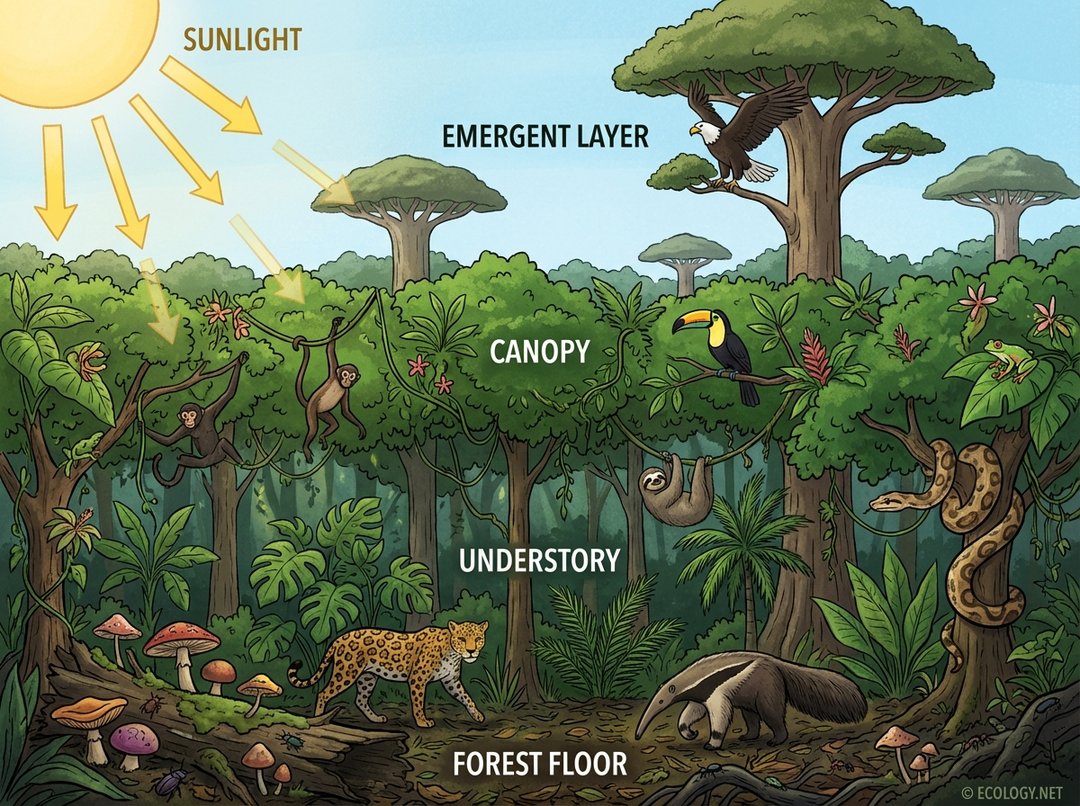

The Vertical World: Layers of Life in the Rainforest

One of the most striking features of a tropical rainforest is its distinct vertical structure. Life is not uniformly distributed but organized into several layers, each with its own unique environmental conditions and specialized inhabitants. This stratification allows for an incredible diversity of niches, enabling countless species to coexist.

Let us explore these fascinating layers from the ground up:

- The Forest Floor: This is the darkest and most humid layer, receiving less than 2 percent of the sunlight. It is relatively clear of vegetation due to the lack of light, but it is a bustling hub of decomposition. Fungi, bacteria, and insects thrive here, rapidly breaking down fallen leaves, branches, and dead animals, recycling vital nutrients back into the ecosystem. Large mammals like jaguars and tapirs often roam this layer.

- The Understory: Just above the forest floor, the understory is a dense tangle of smaller trees, shrubs, and saplings that are adapted to low light conditions. Plants here rarely grow taller than 15 feet. The air is still and humid, and many insects, amphibians, and reptiles make their home in this layer.

- The Canopy: This is arguably the most vibrant and species-rich layer of the rainforest. Forming a continuous, interlocking roof of leaves and branches, the canopy can be 60 to 100 feet above the ground. It intercepts most of the sunlight and rainfall, creating a rich habitat for an extraordinary variety of animals, including monkeys, sloths, birds, and countless insects. Many plants, known as epiphytes, grow on the branches of canopy trees, never touching the ground.

- The Emergent Layer: Soaring above the canopy, the emergent layer consists of a few scattered, giant trees that can reach heights of over 200 feet. These majestic trees are exposed to intense sunlight, strong winds, and extreme temperatures. Eagles, harpy eagles, and other large birds of prey often perch here, surveying their vast domain.

This vertical arrangement is fundamental to understanding how rainforests function and support such immense biodiversity.

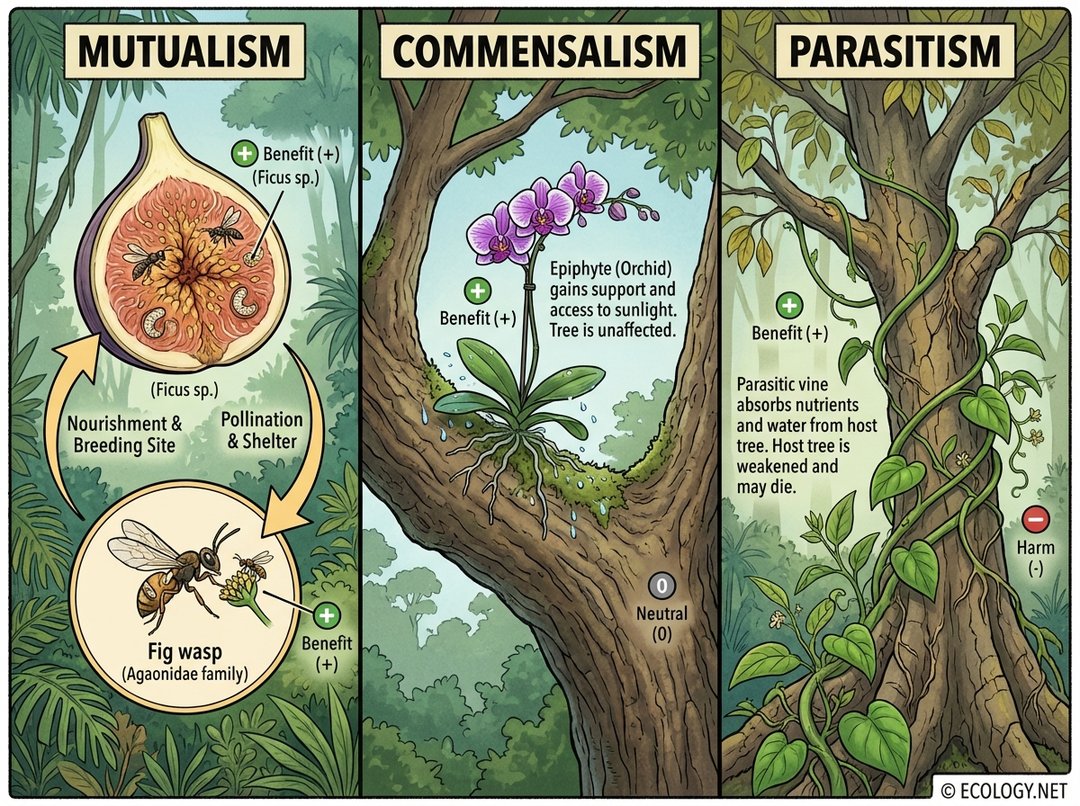

Symbiotic Relationships: A Web of Connections

The sheer density and diversity of life in rainforests lead to incredibly complex interactions between species. Many of these interactions are not competitive but rather cooperative or interdependent, known as symbiotic relationships. Symbiosis is a close and long-term interaction between two different biological organisms. These relationships are crucial for the survival and functioning of the rainforest ecosystem.

There are three primary types of symbiotic relationships commonly observed in rainforests:

- Mutualism: In mutualistic relationships, both organisms involved benefit from the interaction. This is a win-win scenario that often leads to co-evolution, where species evolve together to enhance their mutual benefit.

- Example: The relationship between fig trees and fig wasps is a classic example. Fig wasps pollinate fig flowers, which are enclosed within the fig fruit, and in return, the fig tree provides a safe place for the wasp larvae to develop. Neither species can reproduce without the other.

- Example: Leaf-cutter ants and fungi also share a mutualistic bond. The ants harvest leaves and bring them to their underground nests to cultivate a specific type of fungus, which they then eat. The fungus, in turn, relies on the ants for its food source and protection.

- Commensalism: Commensalism occurs when one organism benefits from the interaction, while the other is neither significantly harmed nor helped.

- Example: Epiphytes, such as orchids and bromeliads, growing on the branches of large rainforest trees demonstrate commensalism. The epiphyte benefits by gaining access to sunlight and moisture high above the forest floor, while the host tree is typically unaffected by its presence.

- Example: Certain insects or small animals may live in the abandoned nests or burrows of larger animals, gaining shelter without impacting the original occupant.

- Parasitism: In a parasitic relationship, one organism, the parasite, benefits at the expense of the other, the host, which is harmed.

- Example: Strangler figs begin their lives as epiphytes, growing on a host tree. As they grow, their roots descend to the ground and envelop the host tree, eventually “strangling” it and outcompeting it for light and nutrients. The fig benefits, while the host tree is ultimately killed.

- Example: Various fungi and insects can be parasitic on rainforest plants and animals, drawing nutrients from their hosts and potentially weakening or killing them.

These intricate relationships highlight the interconnectedness of rainforest life, where the survival of one species can often depend on its interactions with others.

Rainforests and Global Climate: Earth’s Green Lungs

Beyond their incredible biodiversity, rainforests play a critical role in regulating Earth’s climate and maintaining global ecological balance. They are often referred to as the “lungs of the Earth” due to their immense capacity for carbon sequestration and their influence on the global water cycle.

Carbon Sequestration

Rainforests absorb vast quantities of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. This carbon is stored in the trees, plants, and soil, effectively acting as a massive carbon sink. By removing carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas, rainforests help to mitigate climate change and stabilize global temperatures. When rainforests are destroyed, this stored carbon is released back into the atmosphere, exacerbating the greenhouse effect.

The Global Water Cycle

The influence of rainforests on the water cycle is profound. Through a process called transpiration, trees release enormous amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. This moisture contributes to cloud formation and rainfall, not only locally within the rainforest but also in regions thousands of miles away. For instance, the Amazon rainforest is a major driver of rainfall patterns across South America and beyond. The continuous cycle of evaporation and precipitation helps maintain the high humidity and rainfall characteristic of these ecosystems.

The intricate interplay between rainforests and the atmosphere underscores their indispensable role in maintaining a habitable planet. Their destruction has far-reaching consequences that extend well beyond their geographical boundaries.

Threats and Conservation: Protecting Our Green Treasures

Despite their immense value, rainforests worldwide face severe threats, primarily driven by human activities. The rapid pace of deforestation is perhaps the most pressing concern, leading to irreversible loss of biodiversity and significant contributions to climate change.

Major Threats to Rainforests:

- Deforestation for Agriculture: Large areas of rainforest are cleared for cattle ranching, soy cultivation, and palm oil plantations. These agricultural expansions are often unsustainable and lead to rapid soil degradation.

- Logging: Illegal and unsustainable logging practices remove valuable timber, fragmenting habitats and disrupting the delicate ecosystem balance.

- Mining: The extraction of minerals like gold, iron, and bauxite often involves clearing vast tracts of forest, polluting water sources, and destroying habitats.

- Infrastructure Development: Roads, dams, and other infrastructure projects open up previously inaccessible areas, leading to further encroachment and deforestation.

- Climate Change: Rising global temperatures and altered rainfall patterns can stress rainforest ecosystems, making them more vulnerable to fires and disease.

Consequences of Rainforest Destruction:

- Biodiversity Loss: Millions of species, many yet undiscovered, are lost forever as their habitats are destroyed. This represents an irreplaceable loss to Earth’s natural heritage.

- Climate Change Acceleration: The release of stored carbon from cleared forests contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, accelerating global warming.

- Disruption of Water Cycles: Deforestation can lead to reduced rainfall, increased drought, and altered weather patterns, impacting both local and distant regions.

- Loss of Indigenous Cultures: Many indigenous communities rely directly on rainforests for their livelihoods and cultural identity. Their displacement and the destruction of their ancestral lands represent a profound human tragedy.

- Potential Loss of Medicines: A significant number of modern medicines are derived from rainforest plants. The destruction of these ecosystems means losing potential cures for future diseases.

Conservation Efforts:

Protecting rainforests requires a multi-faceted approach involving governments, international organizations, local communities, and individuals. Key strategies include:

- Establishing Protected Areas: Creating national parks and reserves helps safeguard critical rainforest habitats from exploitation.

- Promoting Sustainable Agriculture and Forestry: Encouraging practices that minimize environmental impact and support local communities.

- Supporting Indigenous Rights: Empowering indigenous communities to manage and protect their traditional lands, as they are often the most effective guardians of the forest.

- Ecotourism: Developing responsible tourism that provides economic incentives for conservation and raises awareness about rainforest importance.

- International Cooperation: Global efforts to combat illegal logging, regulate trade in rainforest products, and provide financial support for conservation initiatives.

Conclusion

Rainforests are extraordinary ecosystems, vital for the health of our planet and the well-being of all its inhabitants. Their unparalleled biodiversity, complex ecological interactions, and critical role in climate regulation make them indispensable natural assets. From the towering emergent trees to the bustling forest floor, every layer and every species contributes to a magnificent web of life that continues to inspire awe and scientific discovery.

The challenges facing rainforests are immense, but so too is the potential for positive change. By understanding their intricate workings, recognizing their global importance, and actively supporting conservation efforts, humanity can ensure that these green treasures continue to thrive for generations to come. The future of rainforests, and indeed much of life on Earth, rests on our collective commitment to their protection.