Imagine a world born anew, a landscape utterly devoid of life, perhaps a fresh volcanic island emerging from the ocean or a barren rock face exposed by a retreating glacier. How does life begin its tenacious march on such a desolate canvas? This incredible process, one of nature’s most profound transformations, is known as primary succession. It is the story of how ecosystems rise from nothing, slowly but surely, turning sterile ground into vibrant, thriving communities.

Primary succession is a fundamental ecological process describing the sequential colonisation of a habitat that has never before supported life. Unlike secondary succession, which occurs in areas where a pre-existing community has been disturbed or removed (like after a forest fire), primary succession starts from scratch. It is a testament to life’s resilience and its remarkable ability to engineer its own environment.

The Bare Beginning: Pioneers of the New World

The initial stage of primary succession is perhaps the most challenging. The environment is harsh, with no soil, extreme temperatures, and a scarcity of nutrients and water. Yet, certain organisms are uniquely adapted to brave these conditions. These are the pioneer species.

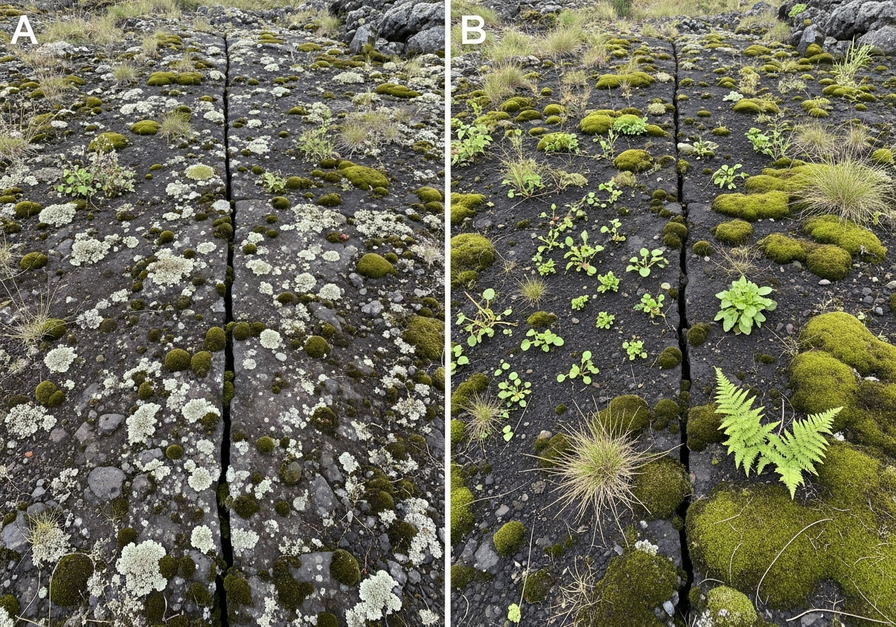

On a freshly formed volcanic rock, for instance, the first signs of life are often microscopic, but their impact is monumental. Lichens, symbiotic organisms composed of fungi and algae, are among the most famous pioneers. They cling to the rock surface, slowly breaking it down both physically and chemically. Their fungal component secretes acids that etch into the rock, while the algal component photosynthesises, providing energy. Mosses soon follow, finding purchase in the tiny crevices created by lichens and trapping moisture and dust.

This image depicts the very first stage of primary succession, showing how pioneer species such as lichens and mosses colonise barren volcanic surfaces and begin the soil-forming process.

These early colonisers might seem insignificant, but they are the unsung heroes of ecosystem development. They perform the crucial first step: creating the very foundation for future life. As lichens and mosses grow, die, and decompose, they contribute organic matter, slowly mixing with weathered rock particles to form the rudimentary beginnings of soil. This nascent soil is thin, nutrient-poor, but it is enough to support the next wave of life.

From Rock to Richness: Building the Soil Foundation

Once a thin layer of organic matter and weathered rock accumulates, the environment becomes slightly less hostile. This allows for the establishment of more complex, yet still hardy, plant species. Small annual plants, grasses, and ferns are typically the next to arrive. Their shallow root systems further break down the rock, and their decaying biomass adds more organic material to the developing soil.

The presence of these plants also begins to alter the microclimate. They provide some shade, reducing extreme temperature fluctuations, and their roots help to retain moisture. This creates a more hospitable environment for a wider array of microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, which are vital for nutrient cycling and further soil development. The soil slowly deepens, becoming richer in nutrients and more capable of holding water.

This illustration visualises the progression from bare rock to developing soil and early plant life, highlighting the key changes that occur during the intermediate phases of primary succession.

This intermediate stage is a period of rapid change and increasing complexity. The community shifts from being dominated by simple, stress-tolerant species to including those that require more developed soil and slightly more stable conditions. Insects and other small invertebrates begin to colonise the area, attracted by the new plant life, further contributing to the ecosystem’s burgeoning biodiversity.

The March of Life: Intermediate Stages and Beyond

As the soil continues to deepen and enrich, larger, longer-lived plants can take root. Shrubs and small trees, often those with nitrogen-fixing capabilities (like alders on glacial moraines), become established. These plants cast more shade, further modifying the light and temperature conditions at ground level. This shading can outcompete the earlier successional species, leading to a shift in the dominant plant community.

The increasing structural complexity of the vegetation provides more habitats and food sources, attracting a greater diversity of animal life, including birds and small mammals. These animals, in turn, play roles in seed dispersal, pollination, and nutrient cycling, accelerating the successional process. Each stage builds upon the last, creating conditions that favor new species while often making the environment less suitable for the previous inhabitants.

The Grand Finale: Climax Communities

Eventually, if left undisturbed for a sufficient period, the ecosystem reaches a relatively stable state known as a climax community. This community is characterised by its high biodiversity, complex food webs, and a balance between species. The dominant plant species are typically large, long-lived trees in many terrestrial environments, forming a mature forest. The soil is deep, rich, and well-structured, supporting a vast network of roots, fungi, and microorganisms.

A climax community is not static; it is a dynamic equilibrium. While the species composition may remain relatively stable over long periods, individual organisms are born, grow, and die, and the community can still experience minor fluctuations due to natural events like storms or disease. However, it possesses a remarkable resilience, capable of recovering from small disturbances and maintaining its overall structure and function.

This image represents the climax community stage of primary succession, showing a stable, biodiverse ecosystem that has developed after years of soil accumulation and species colonisation.

Examples of climax communities include the majestic old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest, the vast grasslands of the African savanna, or the intricate coral reefs of tropical oceans. Each is a culmination of centuries or even millennia of primary succession, a testament to the power of ecological processes.

Factors Influencing Primary Succession

While the general sequence of primary succession is broadly similar across different environments, the specific species involved and the rate of change are influenced by several key factors:

- Climate: Temperature, rainfall, and sunlight dictate which species can survive and thrive. A tropical climate will support a very different successional sequence than an arctic one.

- Topography: The slope, aspect (direction it faces), and elevation of the land influence water retention, sun exposure, and soil stability, all of which affect colonisation patterns.

- Availability of Propagules: The proximity of seed sources, spores, or other reproductive structures is crucial. Areas isolated from existing life will experience slower colonisation.

- Time Scale: Primary succession is a slow process, often taking hundreds to thousands of years to reach a climax community, particularly in harsh environments.

- Disturbances: While primary succession starts in undisturbed areas, subsequent disturbances (like volcanic eruptions, landslides, or human activity) can reset the process or alter its trajectory, leading to a mosaic of successional stages across a landscape.

Why Does Primary Succession Matter?

Understanding primary succession is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for ecology, conservation, and even our understanding of planetary processes:

- Ecological Resilience: It demonstrates how ecosystems can recover and rebuild from extreme events, highlighting nature’s inherent capacity for self-organisation.

- Biodiversity Conservation: By understanding the stages of succession, conservationists can better manage habitats and protect species that are characteristic of specific successional phases.

- Restoration Ecology: Knowledge of primary succession principles is invaluable for restoring degraded lands, such as reclaiming mining sites or re-establishing vegetation on barren slopes.

- Climate Change Insights: Studying how ecosystems establish and develop on new land provides insights into how species might adapt to changing environments or colonise newly exposed areas due to glacial retreat.

The journey from barren rock to a thriving ecosystem is one of nature’s most compelling narratives. Primary succession is a slow, relentless dance of life, where each organism, from the humble lichen to the towering tree, plays a vital role in transforming the environment. It is a powerful reminder of the interconnectedness of all living things and the incredible capacity of life to persist, adapt, and flourish against all odds.