Cultivating Diversity: Unveiling the Power of Polyculture

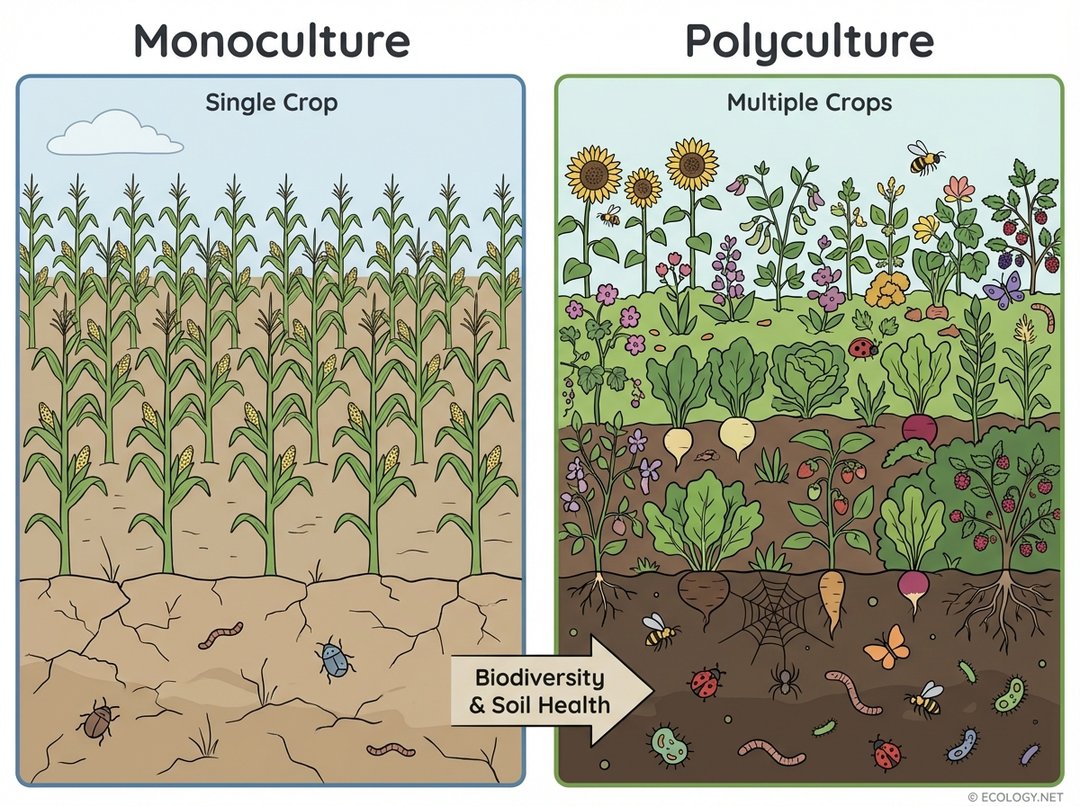

For centuries, agricultural practices have largely favored monoculture, the cultivation of a single crop species over vast areas. While seemingly efficient, this approach often leads to depleted soils, increased vulnerability to pests and diseases, and a significant loss of biodiversity. However, a different philosophy, rooted in ecological wisdom and ancient practices, offers a compelling alternative: polyculture. Polyculture represents a fundamental shift in how food is grown, moving away from uniformity and embracing the inherent strength of diversity.

What is Polyculture? A Fundamental Shift in Agriculture

At its heart, polyculture is the practice of growing multiple crop species in the same space at the same time. Unlike monoculture, which simplifies an ecosystem, polyculture seeks to mimic the complexity and resilience found in natural ecosystems. It is about creating a harmonious community of plants that interact beneficially, rather than competing in isolation. This approach leverages ecological principles to foster a more robust and sustainable agricultural system.

Imagine a natural forest: it is not composed of just one type of tree, but a rich tapestry of trees, shrubs, herbs, and fungi, all coexisting and contributing to the health of the whole. Polyculture applies this same logic to farming, recognizing that a diverse plant community can offer greater stability and productivity than a uniform one.

The Ecological Genius of Polyculture: Why It Works

The true brilliance of polyculture lies in its ability to harness synergistic relationships between different plant species. When chosen carefully, plants can support each other in numerous ways, creating a system that is greater than the sum of its parts. This ecological cooperation leads to a cascade of benefits for the entire growing environment.

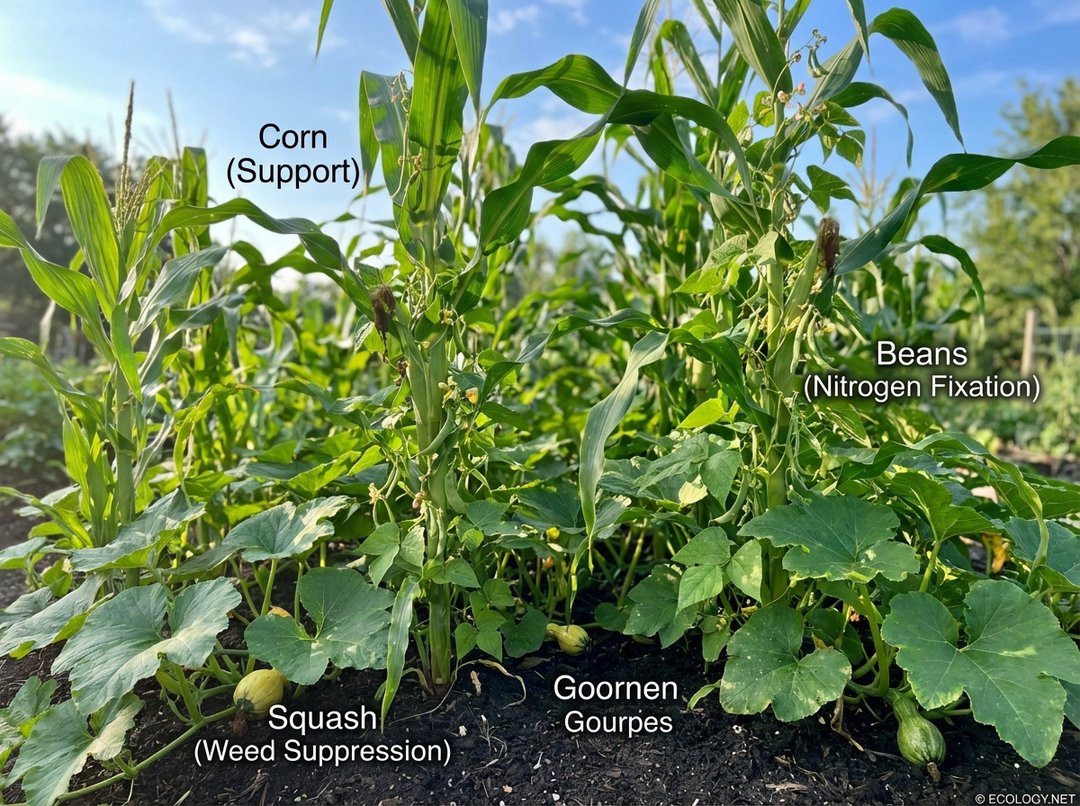

One of the most celebrated examples of polyculture is the “Three Sisters” planting system, a traditional agricultural method practiced by indigenous peoples across North America for thousands of years.

The Three Sisters consist of:

- Corn: Provides a natural trellis for the beans to climb, lifting them off the ground and into the sunlight.

- Beans: As legumes, beans are nitrogen fixers. They draw nitrogen from the air and convert it into a form usable by plants, enriching the soil for themselves and their companions.

- Squash: With its broad leaves, squash spreads across the ground, shading the soil. This helps suppress weeds, retain soil moisture, and deter pests.

This ingenious combination demonstrates how different plants can fulfill distinct roles, creating a self-sustaining and highly productive mini-ecosystem.

Beyond the Garden: Key Benefits of Polyculture

The advantages of polyculture extend far beyond simple yield increases. By working with nature rather than against it, polyculture systems deliver a wide array of ecological and economic benefits.

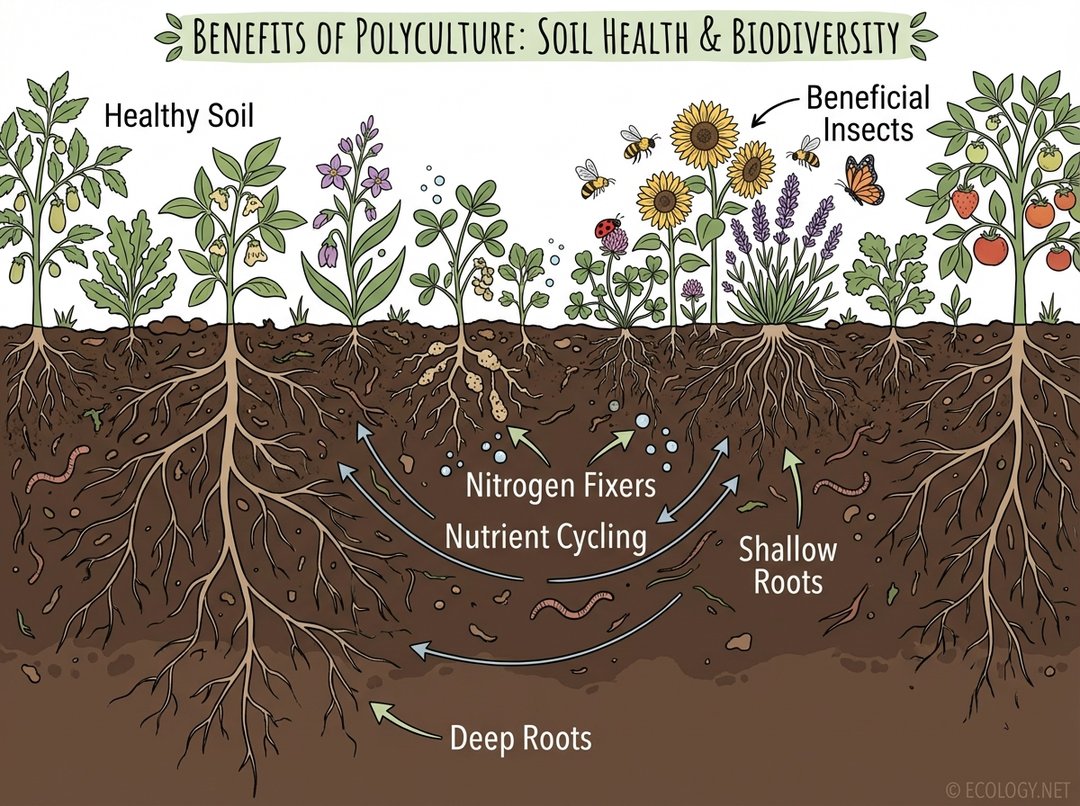

Improved Soil Health

Polyculture fosters a thriving underground ecosystem.

- Diverse Root Systems: Different plants have roots that penetrate the soil at varying depths. This creates channels for water and air, improves soil structure, and allows for the uptake of nutrients from different soil layers.

- Nitrogen Fixation: The inclusion of legumes, such as beans or clover, naturally enriches the soil with nitrogen, a vital plant nutrient, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Increased Organic Matter: A greater diversity of plant residues contributes more organic matter to the soil, enhancing its fertility, water retention capacity, and microbial life.

Increased Biodiversity and Resilience

A diverse plant community supports a diverse array of life above and below ground.

- Attracting Beneficial Insects: A variety of flowering plants provides nectar and pollen for pollinators like bees and butterflies, and habitat for natural predators of pests, such as ladybugs and parasitic wasps.

- Pest and Disease Suppression: The presence of multiple plant species can confuse pests, making it harder for them to locate their preferred host plants. Some plants also release compounds that deter pests or attract their natural enemies. Diseases are less likely to spread rapidly through a mixed planting compared to a monoculture.

- Habitat Creation: Polyculture systems offer a more complex habitat structure, supporting a wider range of wildlife, from soil microorganisms to birds.

Enhanced Productivity and Resource Efficiency

By utilizing resources more effectively, polyculture can often achieve higher overall yields.

- Niche Partitioning: Different plants occupy different ecological niches, utilizing light, water, and nutrients at different times or from different parts of the environment, leading to more complete resource utilization.

- Water and Nutrient Utilization: A diverse root system can access water and nutrients more efficiently, especially during periods of drought or nutrient scarcity.

Reduced Need for External Inputs

The natural processes within a polyculture system can significantly decrease reliance on artificial aids.

- Less demand for synthetic fertilizers due to nitrogen-fixing plants.

- Reduced need for pesticides and herbicides because of natural pest control and weed suppression.

Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation

Polyculture offers solutions for a changing climate.

- Carbon Sequestration: Healthy, diverse soils with increased organic matter are better at storing atmospheric carbon.

- Buffering Against Extreme Weather: Diverse systems are often more resilient to droughts, floods, and temperature fluctuations, ensuring more stable food production.

Types and Examples of Polyculture Systems

Polyculture is not a single method but a broad category encompassing various strategies, each tailored to specific environments and goals.

Intercropping

This involves growing two or more crops in proximity.

- Row Intercropping: Alternating rows of different crops, such as corn and soybeans.

- Strip Intercropping: Growing crops in strips wide enough for independent cultivation, but narrow enough to interact.

- Mixed Intercropping: Completely mixing crops in the same area, like a diverse garden bed of vegetables and herbs.

- Examples: Wheat and lentils grown together, or corn with pumpkins planted between the stalks.

Companion Planting

A specific form of intercropping focused on beneficial plant pairings.

- Selecting plants that provide mutual benefits, such as pest deterrence, growth enhancement, or improved flavor.

- Examples: Marigolds planted near tomatoes to deter nematodes, or basil planted with tomatoes to enhance growth and flavor.

Agroforestry

Integrating trees and shrubs with crops or livestock on the same land.

- Silvopasture: Combining trees, forage, and livestock. Trees provide shade and fodder, while livestock graze and fertilize.

- Alley Cropping: Planting rows of trees or shrubs with agricultural crops cultivated in the alleys between them.

- Benefits: Enhanced biodiversity, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, and diversified income streams.

Permaculture Design

A holistic design philosophy that often incorporates polyculture principles to create self-sustaining, resilient ecosystems.

- Food Forests: Multi-layered plantings mimicking natural forest ecosystems, including canopy trees, understory trees, shrubs, herbaceous plants, groundcovers, and root crops.

- This approach emphasizes long-term sustainability and minimal human intervention once established.

Challenges and Considerations for Implementing Polyculture

While the benefits of polyculture are compelling, its implementation is not without challenges, particularly for large-scale conventional agriculture.

- Complexity in Planning and Management: Designing effective polyculture systems requires a deep understanding of plant interactions, growth habits, and environmental conditions.

- Mechanization Difficulties: Harvesting and cultivation can be more challenging with mixed crops, as standard machinery is often designed for monoculture. This can increase labor requirements.

- Initial Knowledge Barrier: Farmers accustomed to monoculture may need to acquire new knowledge and skills to successfully transition to polyculture.

- Harvesting Challenges: Harvesting multiple crops with different maturation times from the same plot can be more labor-intensive and less amenable to large-scale mechanical harvesting.

Despite these hurdles, innovative solutions and smaller-scale applications continue to demonstrate the viability and immense potential of polyculture.

The Future of Food: Embracing Polyculture for a Sustainable Tomorrow

Polyculture offers a powerful vision for the future of agriculture, one that prioritizes ecological health, resilience, and long-term sustainability. By moving beyond the limitations of monoculture and embracing the wisdom of diversity, humanity can cultivate food systems that are not only productive but also regenerative.

As the global population grows and environmental challenges intensify, the principles of polyculture become increasingly vital. It is a pathway to healthier soils, richer biodiversity, more stable food production, and a more harmonious relationship with the natural world. Embracing polyculture is not just about growing food differently; it is about rethinking our connection to the land and building a more resilient future for all.