The Sweet Life: Unveiling the World of Nectarivores

In the intricate tapestry of life, some creatures have found their niche by tapping into one of nature’s most delightful resources: nectar. These specialized animals, known as nectarivores, play a vital role in ecosystems worldwide, often forming indispensable partnerships with flowering plants. Far more diverse than just the buzzing bees and hovering hummingbirds we commonly imagine, the world of nectarivores is a testament to evolution’s ingenuity, showcasing an array of fascinating adaptations and ecological connections.

Beyond the Obvious: Who are the Nectarivores?

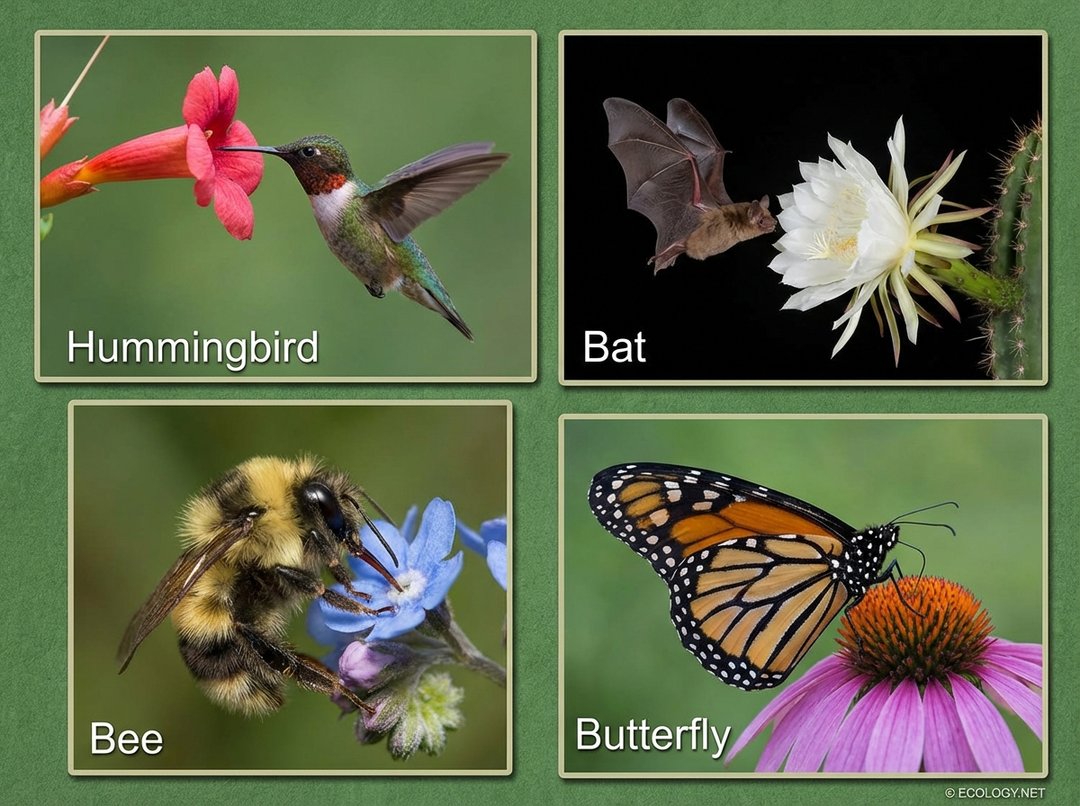

When thinking of nectar feeders, images of delicate butterflies fluttering from blossom to blossom or tiny hummingbirds darting between flowers often come to mind. These are indeed quintessential nectarivores, but the family tree of nectar-loving animals extends far wider, encompassing a surprising variety of species across different taxonomic groups.

- Insects: Bees, butterflies, moths, and certain flies and beetles are perhaps the most well-known insect nectarivores. Their sheer numbers and diversity make them critical players in many ecosystems.

- Birds: Hummingbirds in the Americas and sunbirds in Africa and Asia are iconic examples, known for their rapid wingbeats and specialized bills.

- Mammals: While less common, some mammals are dedicated nectarivores. Bats, particularly fruit bats and nectar bats, are crucial pollinators in tropical and subtropical regions. Certain marsupials, like honey possums in Australia, also rely heavily on nectar.

- Reptiles: Even some reptiles, such as certain gecko species, have been observed feeding on nectar.

This incredible diversity highlights how a simple sugar solution can drive complex evolutionary pathways and ecological interactions across the globe.

Nectar: The Sweet Fuel of Life

At its core, nectar is a sugar rich liquid produced by flowering plants, primarily to attract pollinators. It is secreted by specialized glands called nectaries, which can be located within the flower or on other parts of the plant. While primarily composed of sugars like sucrose, glucose, and fructose, nectar can also contain trace amounts of amino acids, vitamins, minerals, and volatile compounds that contribute to its scent.

The specific composition and concentration of nectar vary greatly between plant species, often tailored to attract particular types of nectarivores. For instance, flowers pollinated by hummingbirds tend to produce large volumes of dilute, sugar rich nectar, while those pollinated by bats might offer a more protein rich blend. This sweet reward serves as a vital energy source for nectarivores, fueling their active lifestyles and reproductive efforts.

Morphological Adaptations: Built for the Feast

The pursuit of nectar has driven the evolution of some truly remarkable physical adaptations. Nectarivores possess specialized tools that allow them to efficiently access and consume this precious resource, often reflecting a coevolutionary dance with the plants they visit.

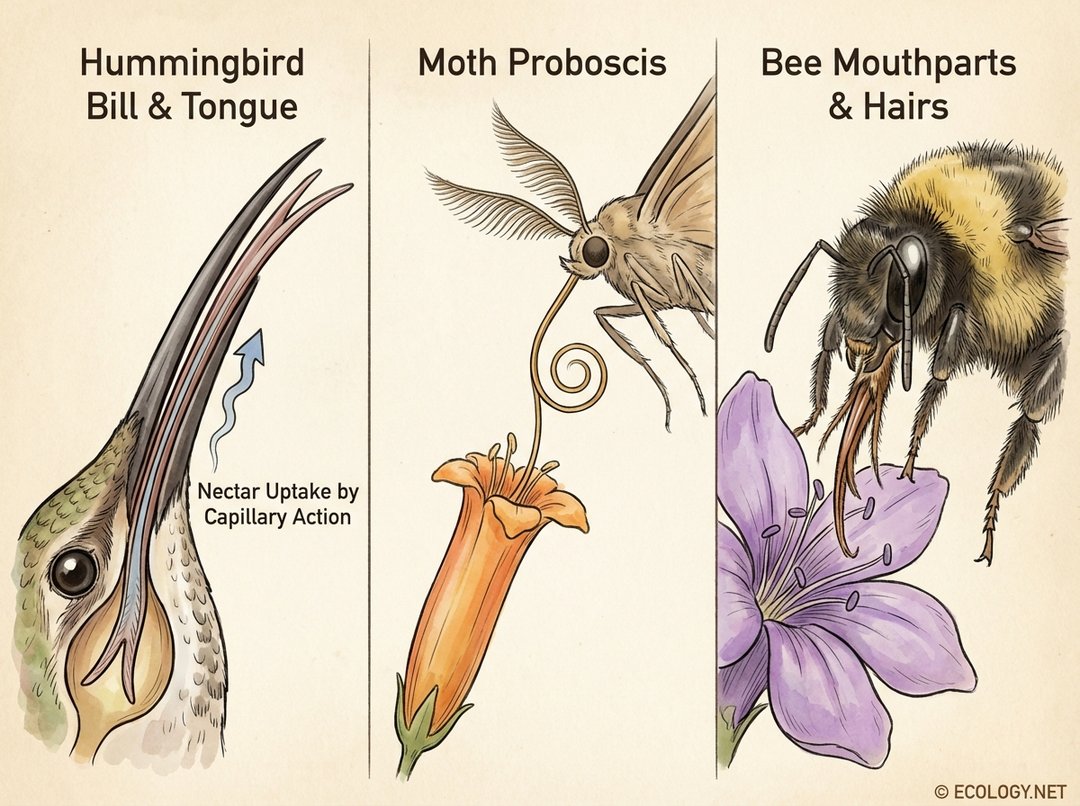

Hummingbird Bills and Tongues

Hummingbirds are masters of aerial acrobatics and nectar extraction. Their long, slender bills are perfectly shaped to reach deep into tubular flowers. Even more fascinating is their tongue, which is not a simple straw but a forked, grooved structure. When extended, the edges of the tongue curl inward, forming two tiny tubes that can rapidly wick up nectar through capillary action, much like a tiny pump.

Moth and Butterfly Proboscises

Butterflies and moths possess a unique feeding tube called a proboscis. This long, coiled structure, which resembles a miniature party blower when at rest, can extend to impressive lengths, allowing these insects to probe deep into flower corollas. The proboscis acts like a straw, enabling them to suck up nectar. The length and flexibility of the proboscis are often highly adapted to the specific flowers they visit.

Bee Mouthparts and Hairs

Bees have a complex set of mouthparts, including a tongue like glossa that can lap up nectar. Many species also have specialized hairs on their bodies, particularly on their legs, which are crucial for collecting and transporting pollen, a byproduct of their nectar foraging. This dual function makes bees incredibly efficient pollinators.

Bat Tongues

Nectar feeding bats have evolved exceptionally long, extensible tongues, sometimes reaching up to one and a half times their body length. These tongues are often covered in brush like papillae, which increase the surface area for nectar absorption, allowing them to quickly lap up large quantities of liquid.

Pollination: A Mutualistic Relationship

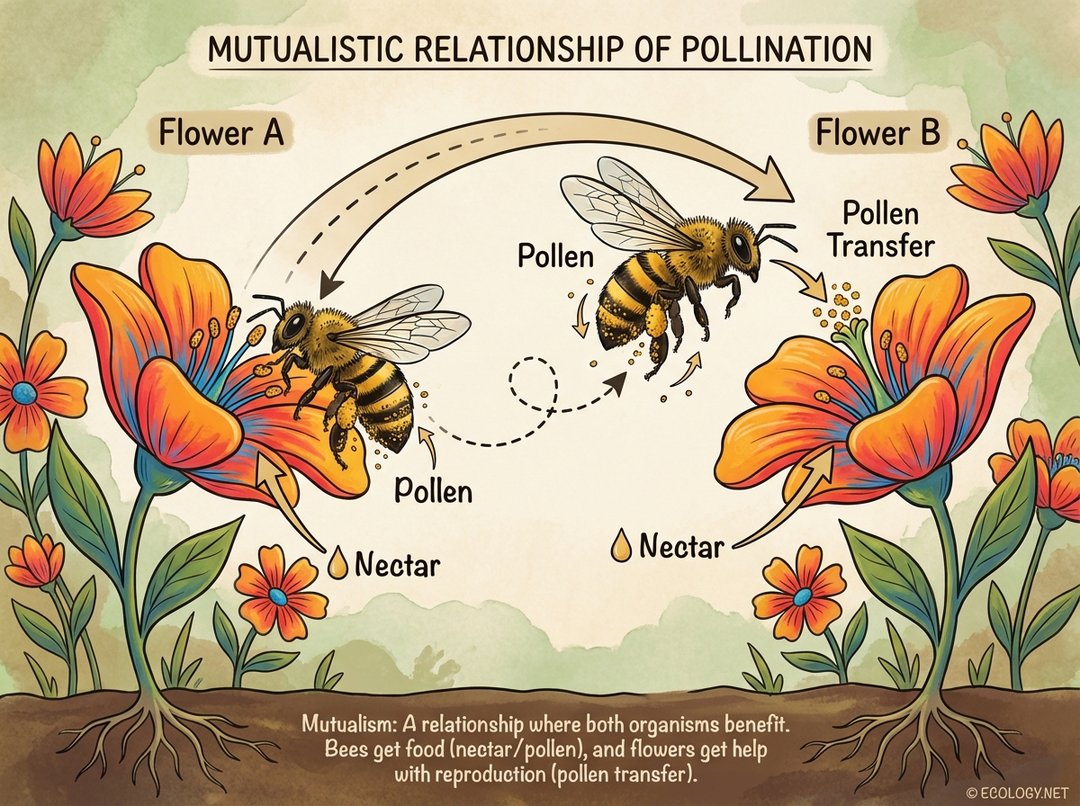

The most celebrated and ecologically significant role of nectarivores is their involvement in pollination. This is a classic example of a mutualistic relationship, where both the nectarivore and the plant benefit.

The Process of Pollen Transfer

When a nectarivore visits a flower to drink nectar, it inadvertently brushes against the flower’s anthers, which are covered in pollen. The pollen grains stick to the animal’s body, often to specialized hairs or feathers. As the nectarivore then flies or crawls to another flower of the same species, some of this pollen is transferred to the stigma of the new flower, initiating fertilization. This transfer of pollen is essential for the plant’s reproduction, leading to the formation of seeds and fruits.

Ecological Importance

Without nectarivores, many flowering plants would struggle to reproduce, leading to a cascade of negative effects throughout ecosystems. Pollinators are responsible for the reproduction of a vast majority of wild plants and a significant portion of the crops that feed humanity. From the fruits and vegetables we eat to the fibers we use, the silent work of nectarivores underpins much of our world.

Beyond Pollination: Other Ecological Roles

While pollination is their most prominent role, nectarivores contribute to ecosystems in other subtle yet important ways:

- Food Web Dynamics: Nectarivores themselves serve as a food source for predators, linking the energy from plants into higher trophic levels.

- Indicators of Ecosystem Health: Healthy populations of diverse nectarivores often indicate a thriving and biodiverse ecosystem. Declines in nectarivore populations can signal environmental problems such as habitat loss or pesticide contamination.

- Seed Dispersal (Indirectly): While not direct seed dispersers, the health of plant populations reliant on nectarivore pollination directly impacts the availability of fruits and seeds for other animals that *do* disperse them.

Challenges and Conservation

Despite their critical importance, nectarivore populations worldwide face numerous threats. Habitat loss and fragmentation, largely due to urbanization and agricultural expansion, reduce the availability of the flowering plants they depend on. The widespread use of pesticides, particularly systemic insecticides, can directly harm nectarivores or contaminate their food sources. Climate change also poses a significant challenge, altering flowering times and potentially creating mismatches between nectarivore emergence and floral availability.

Protecting nectarivores requires a multi faceted approach:

- Habitat Restoration: Planting native, nectar rich flowers in gardens, parks, and agricultural margins.

- Reducing Pesticide Use: Adopting organic farming practices and minimizing chemical applications in landscapes.

- Creating Pollinator Corridors: Connecting fragmented habitats to allow nectarivores to move freely between food sources.

- Public Awareness: Educating communities about the importance of nectarivores and how to support them.

A World Sustained by Sweetness

The world of nectarivores is a vibrant and essential component of our planet’s biodiversity. From the smallest bee to the largest nectar bat, these creatures are not merely consumers of sweet liquid; they are architects of life, driving the reproduction of countless plants and sustaining entire ecosystems. Understanding their intricate adaptations and vital ecological roles fosters a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance of nature and underscores our responsibility to protect these invaluable partners in the sweet dance of life.