The Epic Journeys: Unraveling the Mysteries of Animal Migration

Across continents, through vast oceans, and over towering mountain ranges, life on Earth embarks on some of the most extraordinary journeys imaginable. These are the epic migrations, annual spectacles of endurance, instinct, and navigation that have captivated humanity for millennia. From the smallest insects to the largest whales, countless species undertake these perilous voyages, driven by ancient rhythms and the fundamental needs for survival.

Understanding animal migration offers profound insights into the intricate web of life, the delicate balance of ecosystems, and the incredible adaptations that allow species to thrive in a constantly changing world. Let us delve into the fascinating science behind these remarkable expeditions.

What Defines Migration? A Journey of Purpose

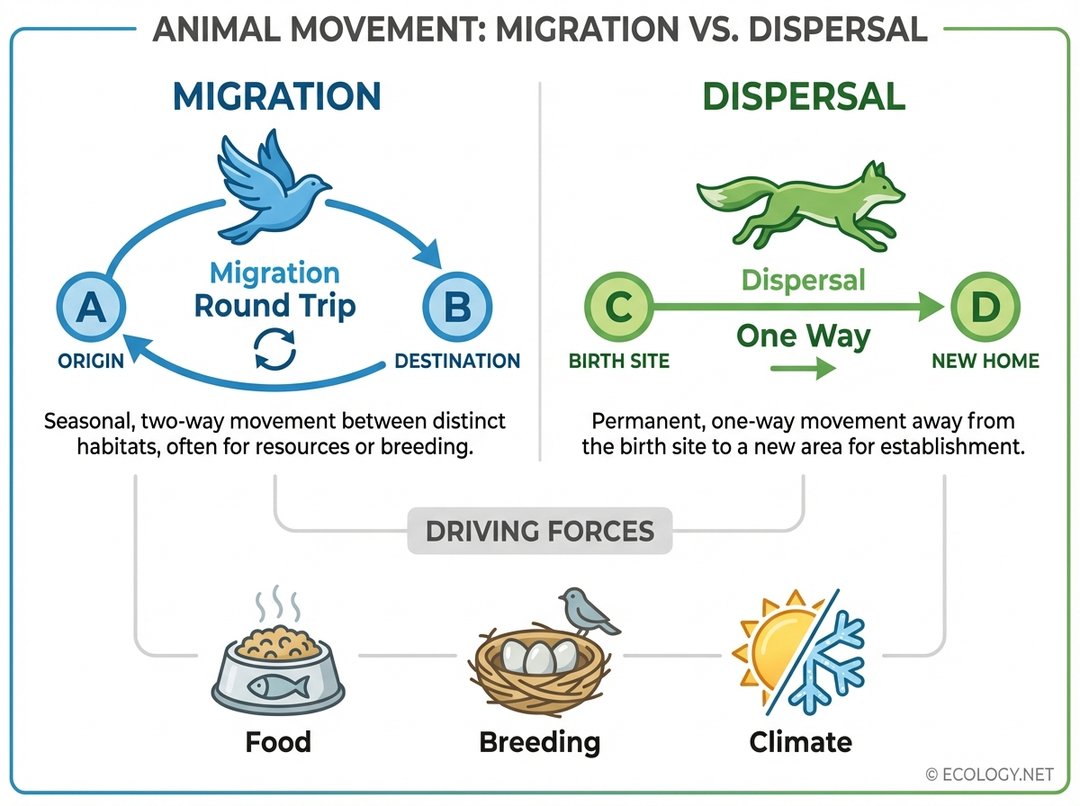

At its core, migration is more than just movement; it is a purposeful, often seasonal, two-way journey undertaken by animals between distinct habitats. It is a predictable pattern, typically occurring annually, driven by specific environmental cues and biological imperatives. This distinguishes it from other forms of animal movement.

To truly grasp the concept, it is helpful to contrast migration with a similar but distinct phenomenon: dispersal. While migration involves a round trip, a return to a previous location or region, dispersal is a one-way movement away from a natal or current area, often by younger individuals seeking new territories or resources. A young bird leaving its nest to find its own territory is dispersing; a swallow flying south for winter and returning north for summer is migrating.

The Driving Forces Behind the Journey

Why do animals undertake such arduous journeys, often risking life and limb? The primary motivators are universal and fundamental to life itself:

- Food Availability: Many environments experience seasonal fluctuations in food resources. For instance, the lush summer pastures of the Arctic become barren in winter, prompting caribou and reindeer to move south in search of forage. Similarly, many bird species migrate to warmer climates where insects and fruits remain abundant during colder months.

- Breeding and Reproduction: Optimal conditions for raising young are often found in different locations than those best for adult survival during other times of the year. Many bird species, for example, migrate to temperate or arctic regions during summer to breed, where longer daylight hours provide ample time for foraging and fewer predators might be present. Sea turtles migrate thousands of miles to specific nesting beaches where they themselves hatched.

- Climate and Temperature: Avoiding harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme cold or intense heat, is a powerful driver. Birds fly south to escape freezing winters, while some fish move to deeper, cooler waters during summer heatwaves. Conversely, some species might migrate to take advantage of favorable temperatures for growth or reproduction.

These factors often work in concert, creating a complex interplay of pressures that shape migratory routes and timings.

Types of Migration: Journeys Across Landscapes and Seas

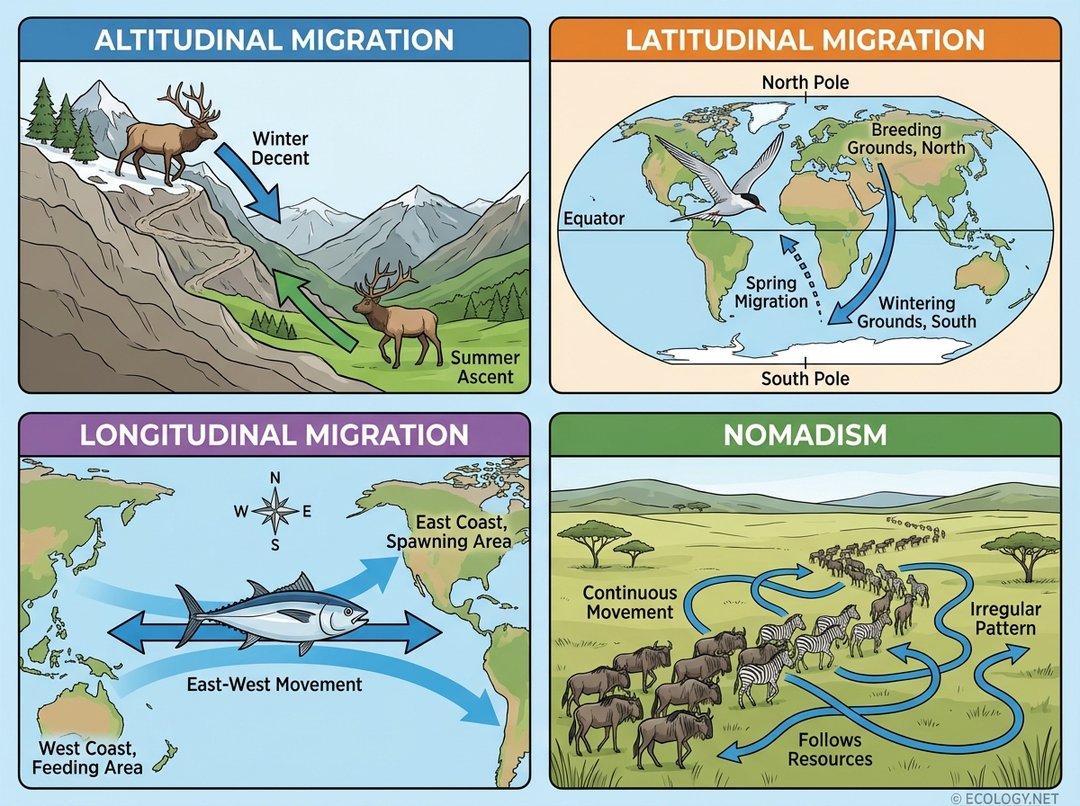

Migration is not a monolithic phenomenon; it manifests in diverse forms, each adapted to the specific ecological needs and geographical constraints of different species. These patterns can be broadly categorized by the direction and nature of the movement.

Here are some of the most common types of migration:

- Altitudinal Migration: This involves movement up and down mountain slopes. Animals like elk, bighorn sheep, and some bird species move to higher elevations during warmer months to access fresh vegetation and cooler temperatures, then descend to lower, more sheltered valleys when winter brings snow and scarcity to the peaks.

- Latitudinal Migration: Perhaps the most widely recognized form, this involves movement between northern and southern regions. The iconic journeys of many bird species, such as swallows, geese, and warblers, flying from their northern breeding grounds to southern wintering areas, exemplify latitudinal migration. The monarch butterfly’s incredible journey from Canada and the US to Mexico is another stunning example.

- Longitudinal Migration: This type of migration involves movement along an east-west axis. While less common than latitudinal movements, it is observed in some fish species that move along coastlines or ocean currents, and in certain land animals that might follow specific resource gradients across wide plains. For example, some caribou herds in North America exhibit significant east-west movements within their broader migratory patterns.

- Nomadism: Unlike the more fixed routes of other migration types, nomadic species move in less predictable, continuous patterns across vast landscapes, often in response to highly variable and patchy resources. Wildebeest in the Serengeti, for instance, undertake a continuous, circular migration driven by rainfall and the availability of fresh grass, without a fixed “home” territory they return to annually in the same way a bird returns to a specific nest site. Some bird species, like crossbills, also exhibit nomadic tendencies, moving to areas where cone crops are abundant.

The Incredible Navigators: How Animals Find Their Way

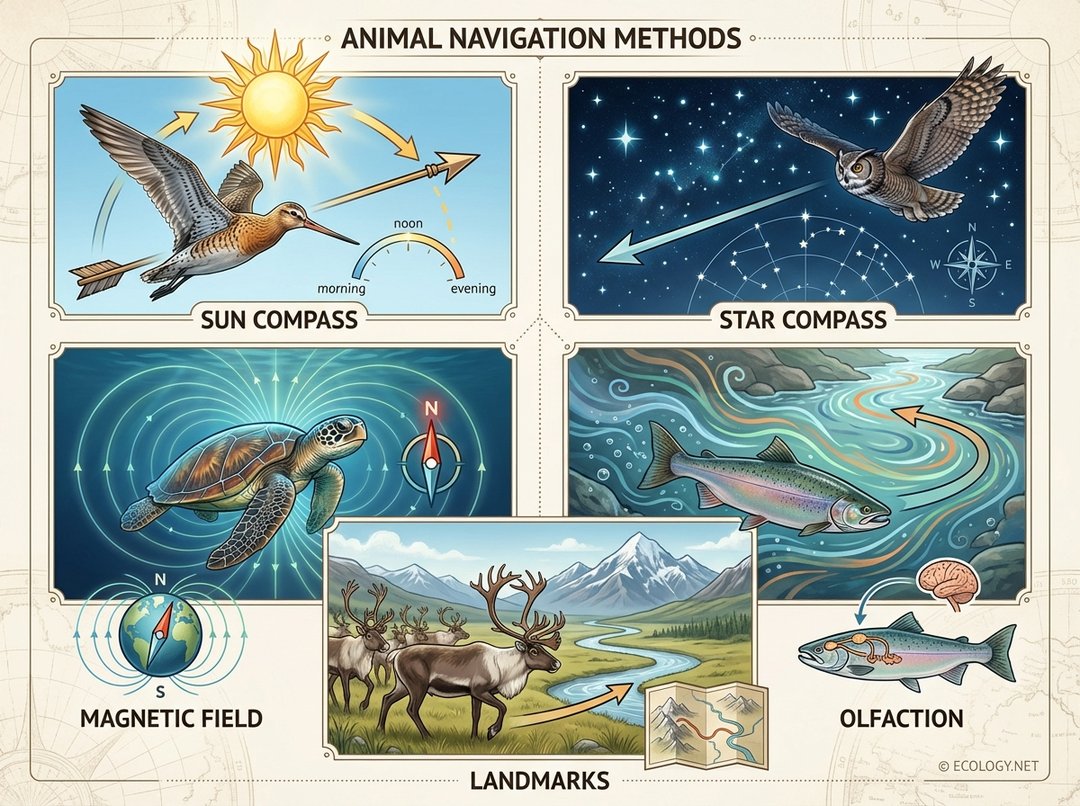

One of the most astonishing aspects of migration is the precision with which animals navigate, often across thousands of miles, to reach specific destinations they may have never seen before. This remarkable feat relies on a sophisticated toolkit of sensory abilities.

Here are some of the key navigational methods employed by migrating animals:

- Sun Compass: Many diurnal (daytime) migrants, particularly birds and insects, use the position of the sun in the sky as a compass. They can compensate for the sun’s movement throughout the day, maintaining a consistent direction. This requires an internal clock to adjust for the sun’s changing azimuth.

- Star Compass: Nocturnal migrants, especially birds, utilize patterns of stars in the night sky, particularly around the North Star (Polaris) in the Northern Hemisphere, to orient themselves. Experiments have shown that young birds can learn these celestial cues.

- Magnetic Field: The Earth’s magnetic field acts as a global positioning system for a wide array of migratory species, including birds, sea turtles, salmon, and even some insects. Animals can detect the inclination (angle) and intensity of the magnetic field, which varies across the globe, allowing them to determine their latitude and direction. Sea turtles, for example, imprint on the unique magnetic signature of their natal beaches.

- Olfaction (Sense of Smell): The sense of smell plays a crucial role for certain migrants, particularly those returning to specific breeding or spawning grounds. Salmon famously navigate back to the precise freshwater streams where they were born, guided by the unique chemical signature of the water. Homing pigeons also use olfactory cues to find their way home.

- Landmarks: For many species, especially larger mammals and birds migrating over familiar terrain, visual landmarks serve as important guides. Mountain ranges, coastlines, major rivers, and even human-made structures can be used to maintain direction or correct course. Young animals often learn these routes by following older, more experienced individuals.

It is important to note that animals rarely rely on a single navigational cue. Instead, they often use a combination of these methods, switching between them depending on environmental conditions (e.g., clear skies versus cloudy nights) and integrating information from multiple senses to create a robust and redundant navigational system.

Challenges and the Future of Migration

Despite their incredible adaptations, migratory species face unprecedented challenges in the modern world. Habitat loss and fragmentation along migratory routes, climate change altering seasonal cues and resource availability, and barriers like fences or dams disrupt ancient pathways. Pollution, overhunting, and direct human disturbance also take a heavy toll.

The conservation of migratory species requires international cooperation and a holistic approach, protecting not just breeding grounds or wintering areas, but the entire network of habitats that support these epic journeys. Understanding the intricacies of migration is not merely an academic exercise; it is vital for ensuring the survival of these magnificent travelers and the health of the ecosystems they connect.

A World in Motion: The Enduring Wonder of Migration

The phenomenon of animal migration is a testament to the power of evolution and the enduring drive of life. It is a complex dance between instinct and environment, a symphony of survival played out on a global stage. Each year, as billions of creatures embark on their incredible odysseys, they remind us of the interconnectedness of our planet and the profound beauty of the natural world. By appreciating and protecting these journeys, we safeguard not only the species themselves but also the rich tapestry of life that makes our world so vibrant and awe-inspiring.