Unveiling the World of Granivores: Nature’s Seed Specialists

In the intricate tapestry of life, every creature plays a vital role, often in ways unseen or underappreciated. Among these unsung heroes are granivores, a diverse group of animals whose lives revolve around one of nature’s most potent packages: the seed. From the smallest ant to the largest rodent, these seed eaters are far more than just consumers; they are architects of ecosystems, drivers of evolution, and essential components of biodiversity. Understanding granivores unlocks a deeper appreciation for the delicate balance that sustains our planet.

What Exactly Are Granivores?

At its core, a granivore is an animal that feeds primarily on seeds. The term itself comes from the Latin words “granum” meaning grain or seed, and “vorare” meaning to devour. While this definition seems straightforward, the world of granivores is astonishingly varied, encompassing a vast array of species across different animal kingdoms. These creatures have evolved specialized adaptations to locate, access, process, and digest seeds, which are often nutrient-dense but well-protected.

Consider the common sparrow, a familiar sight in many gardens, diligently pecking at fallen seeds. Or the industrious squirrel, burying acorns for a future meal. Even tiny weevils can be found boring into seed pods, and ants are renowned for their meticulous collection of seeds, sometimes forming vast underground granaries. This incredible diversity highlights how fundamental seeds are as a food source across various ecological niches.

The granivore diet is not merely about sustenance; it is about tapping into a concentrated source of energy and nutrients. Seeds are essentially embryonic plants, packed with carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and essential minerals, all carefully stored to fuel the initial growth of a new plant. For a granivore, a seed represents a compact, high-energy meal, often available in abundance, especially after fruiting seasons.

The Granivore Diet: More Than Just Seeds

While seeds form the cornerstone of a granivore’s diet, the specific types of seeds consumed can vary widely, influencing the animal’s morphology and behavior. Some granivores are generalists, consuming a broad spectrum of seeds, while others are highly specialized, focusing on particular plant species.

Types of Seeds and Granivore Adaptations

- Small, Abundant Seeds: Many birds, like finches and sparrows, specialize in small, easily digestible seeds. Their beaks are often conical and strong, perfectly adapted for cracking open husks.

- Large, Hard-Shelled Seeds: Rodents such as squirrels and chipmunks are masters of larger, tougher seeds like nuts and acorns. They possess powerful jaws and incisors capable of gnawing through formidable shells.

- Tiny Seeds and Grains: Ants, with their incredible strength relative to their size, can carry seeds many times their own weight back to their colonies. Their mandibles are adapted for gripping and sometimes crushing these small treasures.

- Seeds within Fruits: Some granivores consume fruits primarily for the seeds within, often discarding the fleshy pulp. This can be seen in certain bird species or even bats.

Beyond the physical act of consumption, granivores have developed fascinating strategies to deal with the challenges of a seed-based diet. Some detoxify harmful compounds found in certain seeds, while others employ caching behaviors to store food for leaner times, a practice with profound ecological implications.

Ecological Roles of Granivores: Shaping Ecosystems

The impact of granivores extends far beyond their individual survival. These animals are powerful ecological agents, influencing plant populations, forest regeneration, and the overall structure of ecosystems. Their roles can be broadly categorized into seed predation and seed dispersal, two sides of the same ecological coin.

Seed Predation: A Constant Pressure

The most direct impact of granivores is, of course, the consumption of seeds. This act, often termed seed predation, can significantly reduce the number of seeds available for germination. In some cases, high levels of seed predation can limit the regeneration of certain plant species, thereby influencing the composition of plant communities. For example, if a particular tree species’ seeds are heavily preyed upon by rodents, its population might decline, allowing other, less palatable species to thrive.

However, seed predation is not always detrimental. It can act as a natural thinning mechanism, preventing overcrowding and promoting the growth of stronger, healthier plants from the seeds that do survive. It also plays a crucial role in the food web, transferring energy from plants to animals.

Seed Dispersal: The Moving Agents

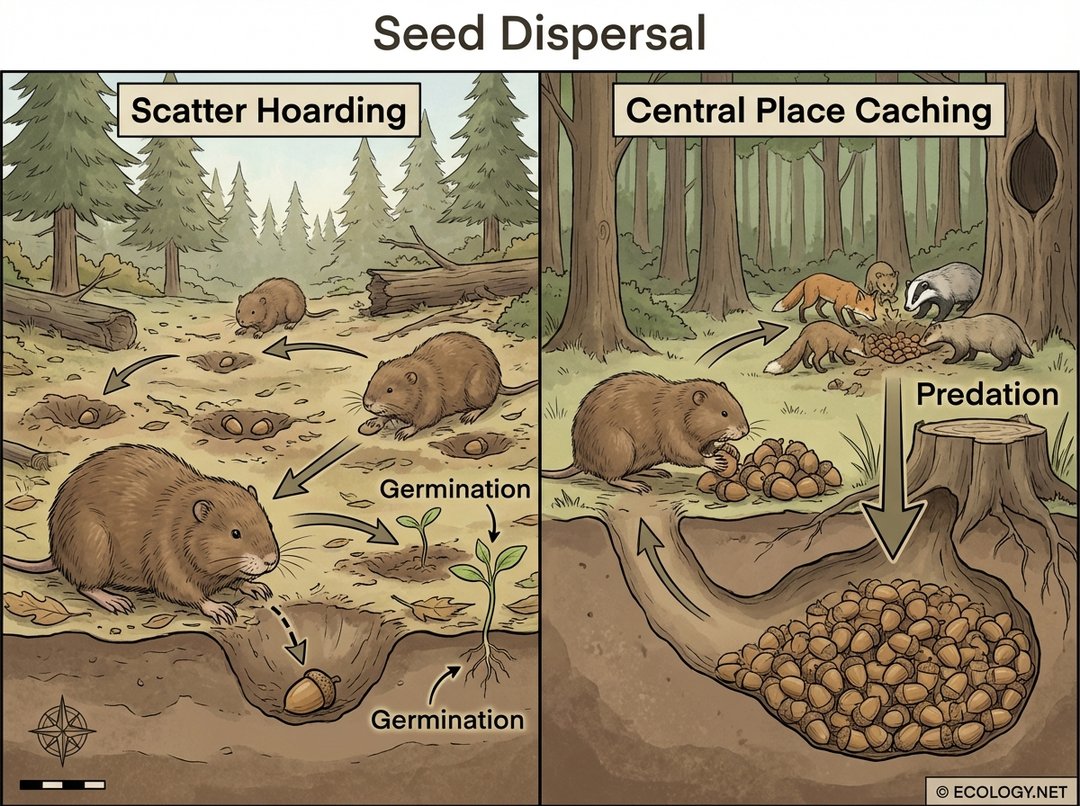

Perhaps one of the most fascinating and beneficial roles of granivores is their contribution to seed dispersal. While many seeds are consumed and destroyed, a significant portion are moved from their parent plant to new locations, often aiding in germination. This happens primarily through two distinct caching strategies:

- Scatter Hoarding: This strategy involves burying individual seeds or small groups of seeds in numerous, widely dispersed caches across a landscape. Animals like squirrels, jays, and some rodents are classic scatter hoarders. They bury seeds for future consumption, but inevitably, some caches are forgotten or abandoned. These unrecovered seeds then have a chance to germinate, often far from the parent plant, leading to successful seed dispersal and forest regeneration. This method reduces the risk of all seeds being lost to a single predator or disease.

- Central Place Caching: In contrast, central place caching involves accumulating many seeds in one large, central location, such as a burrow or a hollow log. While this strategy provides an efficient food source for the granivore, it also concentrates the seeds, making them highly vulnerable to predation by other animals or to spoilage. Consequently, the chances of successful germination from central caches are generally much lower compared to scatter hoarding.

The distinction between these two strategies highlights the complex interplay between a granivore’s feeding behavior and its ecological impact. Scatter hoarders are often considered mutualists, benefiting both themselves and the plants by facilitating dispersal, while central place cachers primarily benefit themselves.

Impact on Ecosystem Structure

By selectively preying on certain seeds and dispersing others, granivores can profoundly influence the distribution and abundance of plant species. They can contribute to the patchiness of vegetation, create new plant communities in previously barren areas, and even help plants colonize new habitats. This dynamic interaction is particularly evident in forest ecosystems, where rodents and birds play a critical role in the regeneration of trees.

Granivores and Ecosystem Health: A Delicate Balance

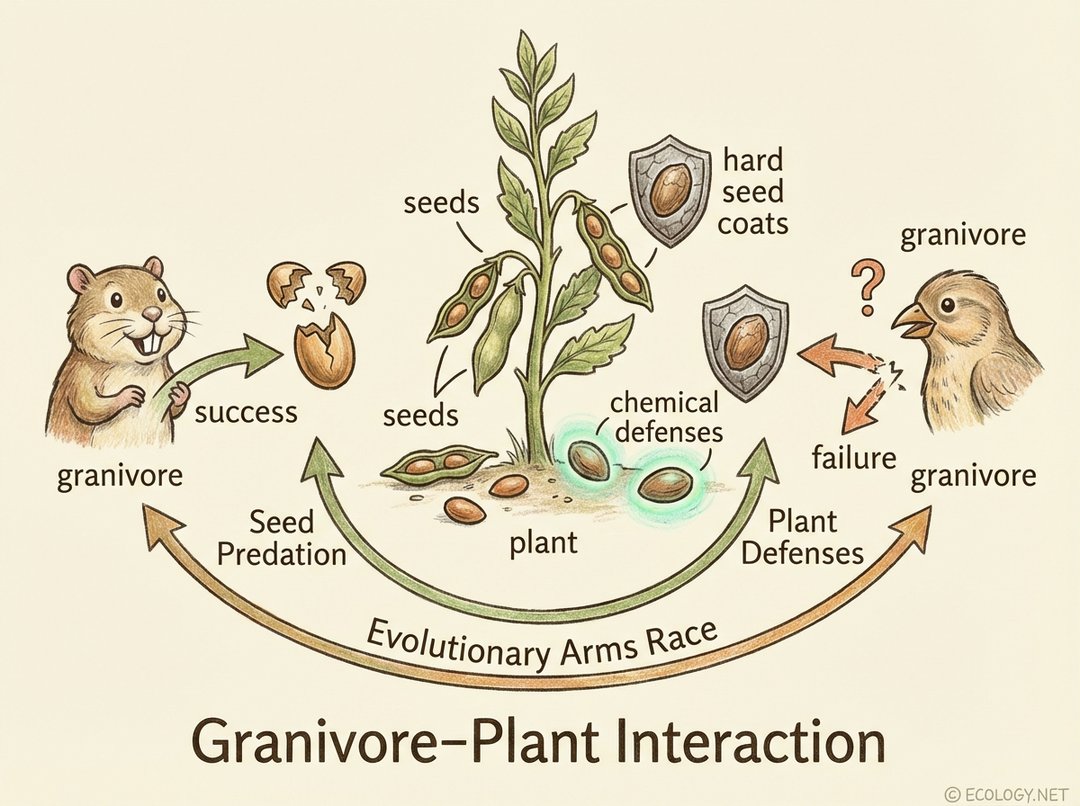

The relationship between granivores and the plants they consume is not static; it is a dynamic, ongoing interaction that has driven evolutionary change for millions of years. This constant back-and-forth is often described as an “evolutionary arms race.”

The Evolutionary Arms Race

Plants, in their endeavor to ensure reproductive success, have developed an astonishing array of defenses to protect their precious seeds from granivores. These defenses can be:

- Physical: Hard seed coats, thorns, or tough husks make seeds difficult to access or consume. Think of the impenetrable shell of a coconut or the hard casing of an acorn.

- Chemical: Many seeds contain toxic compounds, bitter tastes, or digestion inhibitors that deter granivores or make them ill. Cyanide compounds in cherry pits or tannins in acorns are classic examples.

- Temporal: Some plants employ “masting,” producing an overwhelming abundance of seeds in certain years, far more than granivores can consume, ensuring that a significant proportion survives to germinate.

In response, granivores have evolved counter-adaptations. They develop stronger jaws, specialized beaks, detoxification enzymes, or behavioral strategies like caching to overcome plant defenses. This continuous cycle of adaptation and counter-adaptation illustrates the profound co-evolutionary forces at play in nature.

This delicate balance is crucial for ecosystem health. If granivore populations become too high, they can decimate seed banks, hindering plant regeneration. Conversely, if granivore numbers plummet, seed dispersal can suffer, impacting forest health and biodiversity. The presence of a healthy granivore community indicates a thriving, resilient ecosystem.

Challenges and Threats to Granivores

Despite their ecological importance, granivore populations face numerous threats in the modern world. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to urbanization and agriculture directly reduce the areas where these animals can find food and shelter. Pesticide use can inadvertently harm insect granivores and their predators, disrupting food webs. Climate change also poses a significant challenge, altering plant flowering and fruiting times, which can mismatch with granivore breeding cycles and food availability.

Conservation: Protecting Nature’s Gardeners

Recognizing the vital roles granivores play is the first step towards their conservation. Protecting their habitats, promoting sustainable land use practices, and reducing pesticide reliance are essential. By safeguarding these often-overlooked seed specialists, we are not just protecting individual species; we are preserving the intricate ecological processes that underpin healthy, biodiverse ecosystems.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Seed Eaters

From the smallest ant to the largest rodent, granivores are a testament to nature’s ingenuity and interconnectedness. They are not merely consumers of seeds but active participants in the grand cycles of life, driving plant evolution, shaping landscapes, and ensuring the regeneration of forests and grasslands. Their story is one of constant adaptation, delicate balance, and profound ecological significance. By understanding and appreciating the world of granivores, we gain a deeper insight into the vibrant, complex web of life that surrounds us, reminding us of our shared responsibility to protect it.