Imagine standing at the very edge of a dense forest, where the towering trees suddenly give way to an open, sun-drenched meadow. The air feels different here, perhaps a bit breezier, and the sunlight streams in with an intensity not found deep within the woods. You might notice different plants thriving, or hear the calls of birds that prefer this transitional space. This fascinating zone, where two distinct habitats meet, is what ecologists call an “edge,” and the unique set of environmental conditions and ecological responses found there are known as “edge effects.”

What are Edge Effects?

At its core, an edge effect describes the changes in environmental conditions and species composition that occur at the boundary between two different habitats. Think of it as a natural transition zone, a dynamic interface where the characteristics of one habitat bleed into the other. These changes are not just subtle shifts; they can be profound, influencing everything from light levels and temperature to wind patterns and humidity.

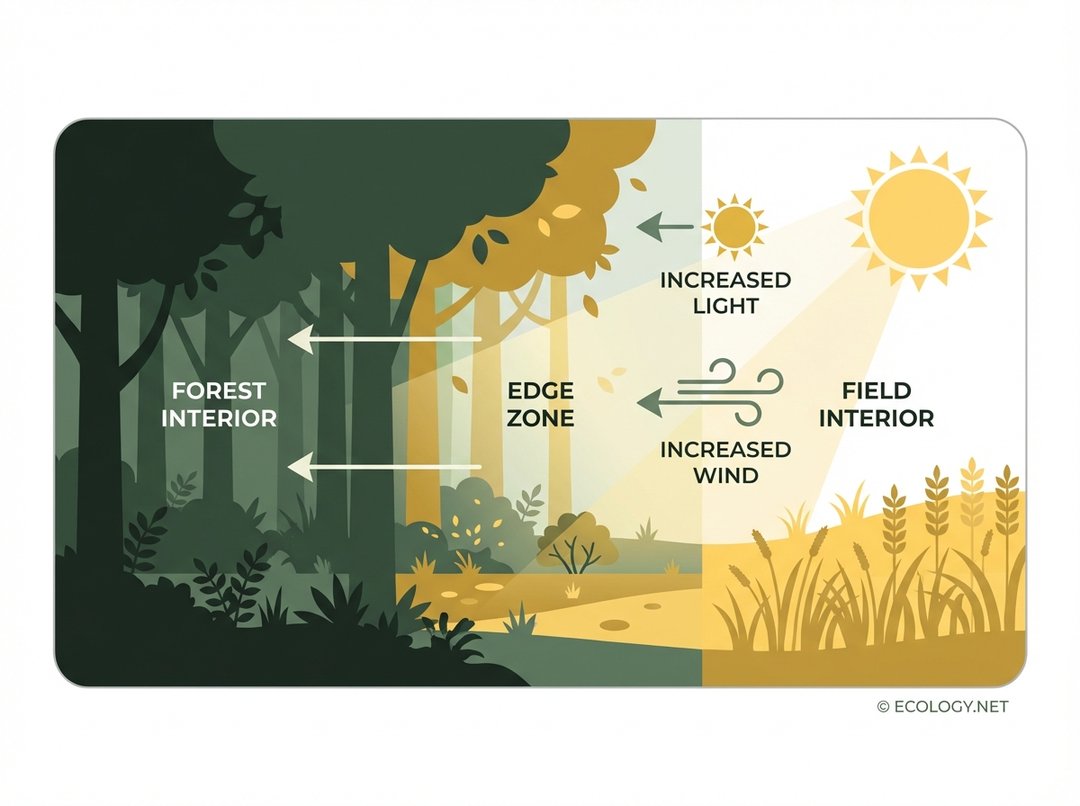

For example, when a forest meets an open field, the forest edge experiences more sunlight and wind exposure than its interior. This increased light can lead to higher temperatures and lower humidity, creating a microclimate distinct from both the deep forest and the open field. These altered conditions, in turn, affect which plants can grow there and which animals choose to live or forage in that specific area.

The image above visually defines edge effects by illustrating this distinct zone where two habitats meet. On one side, a dense forest interior, and on the other, a bright field interior. In between, the ‘Edge Zone’ clearly shows how factors like increased light and wind penetrate from the open habitat into the forest’s periphery. This interaction creates a unique ecological signature, making the edge a place of both opportunity and challenge for various species.

The Science Behind the Boundaries

Understanding edge effects goes beyond simply recognizing a boundary. Ecologists delve into how far these effects extend and how the shape of a habitat influences the proportion of its edge. These factors are critical for predicting how ecosystems respond to changes, especially in a world increasingly shaped by human activities.

Penetration Depth

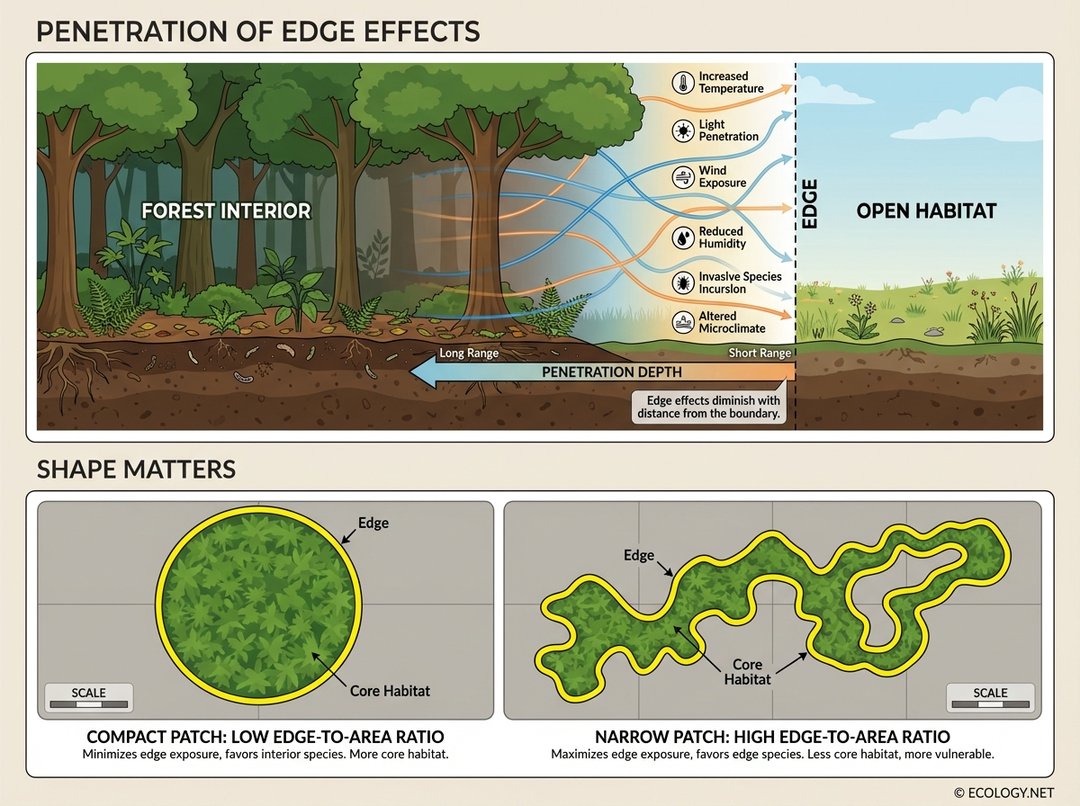

Edge effects do not stop precisely at the line where two habitats meet; they penetrate into the adjacent habitats. The distance these effects extend is known as the “penetration depth.” This depth can vary significantly depending on the specific environmental factor and the type of habitats involved. For instance, changes in light intensity might only penetrate a few meters into a forest, while alterations in wind patterns or humidity could extend much further, sometimes hundreds of meters. The species composition can also show a gradient, with some species preferring the deep interior, others the edge, and some the open habitat.

Shape Matters: Edge-to-Area Ratio

The geometry of a habitat patch plays a crucial role in determining the overall impact of edge effects. Consider two forest patches of the same total area: one is a compact, circular shape, and the other is long, narrow, and highly irregular. The narrow, irregular patch will have a much greater perimeter relative to its total area compared to the compact patch. This is known as the “edge-to-area ratio.”

- Compact Patches: Tend to have a lower edge-to-area ratio, meaning a larger proportion of their interior remains relatively undisturbed by edge effects. These are often considered more resilient for species that require interior habitat conditions.

- Narrow or Irregular Patches: Possess a high edge-to-area ratio, implying that a significant portion, or even the entirety, of the habitat patch is influenced by edge effects. This can have profound implications for the species that can survive within them.

This image clarifies these two crucial advanced concepts. The top section illustrates ‘Penetration of Edge Effects,’ showing how environmental changes extend into the forest interior from the edge. The bottom section, ‘Shape Matters,’ vividly contrasts a compact habitat patch with a low edge-to-area ratio against a narrow, irregular patch with a high edge-to-area ratio. This visual comparison makes it clear how habitat geometry directly influences the extent of edge influence.

The Dual Nature of Edges: Good, Bad, and Complex

Edge effects are not inherently good or bad; their impact is complex and context-dependent. They can create unique opportunities for some species while posing significant challenges for others. This dual nature makes understanding edges vital for conservation and land management.

The “Good” Side: Increased Biodiversity and Unique Niches

Edges often host a greater diversity of species than either of the adjacent habitats alone. This is because they provide access to resources from both ecosystems, creating a unique blend of conditions that some species thrive in. For example:

- Increased Food Sources: A deer might graze in a meadow but retreat into the forest for shelter. The edge provides both.

- Habitat for Generalists: Many species, often referred to as generalists, are well-adapted to the variable conditions of edges. Birds that nest in forest trees but forage in open fields are classic examples.

- Transitional Zones: Edges can act as corridors or stepping stones for species moving between larger habitat patches, facilitating gene flow and population connectivity.

- Unique Microclimates: The specific combination of light, temperature, and humidity at an edge can support plants and insects that are found nowhere else.

The “Bad” Side: Habitat Degradation and Vulnerability

While edges can boost biodiversity, they can also expose habitats to negative influences, especially when edges are created by human activities like deforestation or urbanization. These negative impacts are often more pronounced and can lead to significant ecological decline:

- Increased Predation: Edges can provide easy access for predators into what was once a protected interior habitat. For instance, raccoons or domestic cats might more easily access bird nests at forest edges.

- Invasive Species: Many invasive plants and animals are disturbance-adapted and thrive in the altered conditions of edges. They can quickly colonize these areas and then spread into the native habitat, outcompeting native species. Kudzu vines aggressively taking over forest edges in the southeastern United States are a prime example.

- Environmental Stress: Increased wind, desiccation, and temperature fluctuations at edges can stress native plants and make them more susceptible to disease or insect outbreaks.

- Pollution and Disturbance: Edges adjacent to human development, such as roads or agricultural fields, can suffer from increased noise, light pollution, chemical runoff, and human disturbance, negatively impacting sensitive species.

- Loss of Interior Habitat: For species that require large, undisturbed interior habitats (known as “area-sensitive species”), a high edge-to-area ratio can effectively shrink their usable habitat, leading to population declines.

This image vividly illustrates the ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’ aspects of edge effects. On the left, a healthy forest edge teeming with diverse wildlife, like a deer and a colorful bird, showcases the potential for increased biodiversity. In stark contrast, the right side depicts a disturbed edge, perhaps near human development, where aggressive invasive species are visibly encroaching, highlighting the detrimental impacts. This visual comparison makes the complex implications of edges tangible for the reader.

Managing Edges in a Fragmented World

In an increasingly fragmented landscape, where natural habitats are often broken into smaller patches by human development, understanding and managing edge effects has become a critical aspect of conservation. Land managers and conservationists often strive to:

- Minimize Edge Creation: When new developments or clearings are necessary, designing them to create fewer, more compact habitat patches can reduce the overall edge-to-area ratio.

- Soften Edges: Instead of abrupt transitions, creating gradual, “soft” edges with transitional vegetation can buffer the interior habitat from harsh external conditions and provide more diverse microhabitats.

- Control Invasive Species: Actively managing and removing invasive species from edge zones is crucial to prevent their spread into core habitats.

- Create Corridors: Connecting isolated habitat patches with vegetated corridors can help mitigate the negative effects of fragmentation by allowing species to move safely between areas, even if these corridors themselves are essentially long edges.

Conclusion

Edge effects are a fundamental concept in ecology, revealing the intricate ways in which different habitats interact at their boundaries. Far from being simple lines on a map, edges are dynamic zones of change, influencing everything from microclimates to species diversity. While they can foster unique biodiversity and provide essential resources for some species, they also present significant challenges, particularly when human activities create abrupt and extensive edges. By understanding the science behind these ecological boundaries, we can make more informed decisions about land use, conservation, and how to best protect the rich tapestry of life on Earth.