Deserts, often perceived as barren and lifeless expanses, are in fact some of Earth’s most captivating and resilient ecosystems. Far from being empty, these arid lands teem with unique life forms that have mastered the art of survival in extreme conditions. From scorching sands to icy plateaus, deserts challenge our conventional understanding of what it means for life to thrive, showcasing an extraordinary tapestry of geological wonders, climatic phenomena, and remarkable biological adaptations.

What Defines a Desert?

The defining characteristic of a desert is not necessarily heat or sand, but rather a profound lack of precipitation. Generally, an area is classified as a desert if it receives less than 250 millimeters (approximately 10 inches) of rainfall annually. This scarcity of water dictates everything about these environments, from their geology to the life they support.

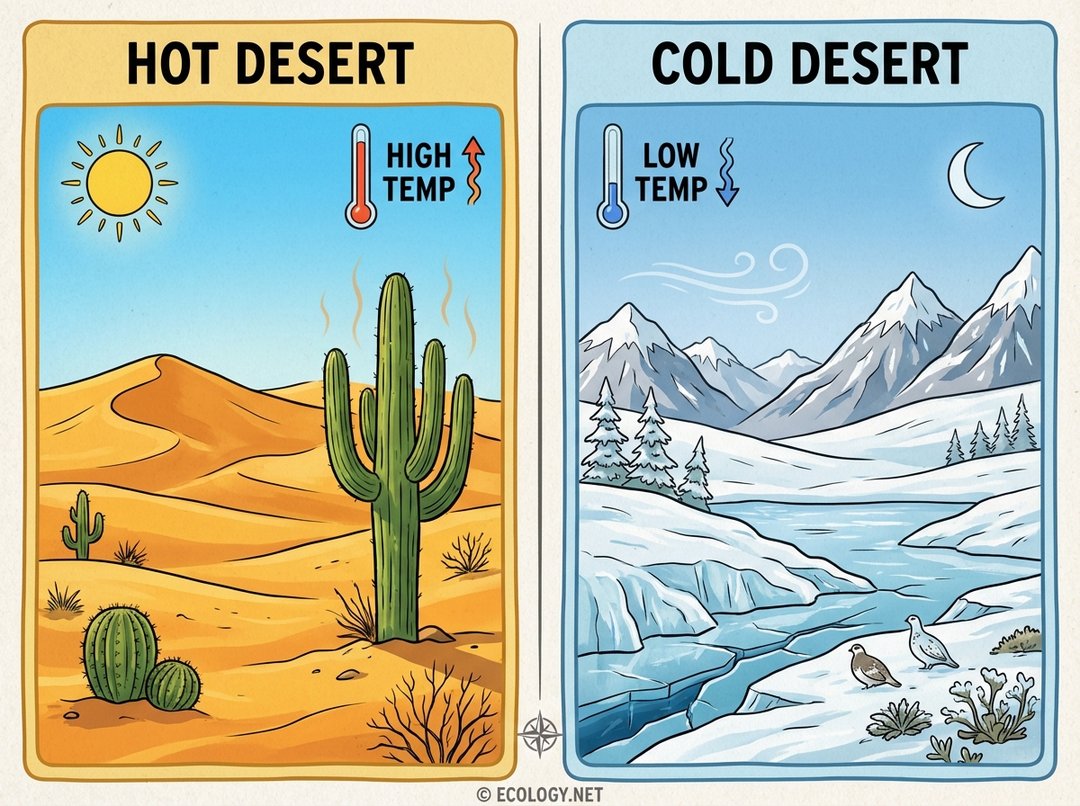

While many envision deserts as scorching hot landscapes, the reality is far more diverse. Deserts can be broadly categorized into two main types based on temperature:

- Hot Deserts: These are the classic deserts with which most people are familiar, characterized by high daytime temperatures, significant temperature drops at night, and often vast stretches of sand dunes. Examples include the Sahara Desert in Africa and the Arabian Desert in the Middle East.

- Cold Deserts: Found in temperate regions or at high altitudes, cold deserts experience extremely low temperatures, especially during winter, and often receive precipitation in the form of snow. Despite the cold, the air remains very dry, leading to arid conditions. The Gobi Desert in Asia and the Great Basin Desert in North America are prime examples.

Understanding this distinction is crucial for appreciating the full spectrum of desert environments.

How are Deserts Formed?

The formation of deserts is a fascinating interplay of global atmospheric circulation, topography, and oceanic influences. Several key mechanisms contribute to these arid conditions:

Subtropical High-Pressure Zones

The most widespread deserts, such as the Sahara and the Australian Outback, are found around 30 degrees latitude north and south of the equator. This is due to global atmospheric circulation patterns known as Hadley cells. Warm, moist air rises at the equator, cools, releases its moisture as rain, and then moves towards the poles. As this dry air descends around 30 degrees latitude, it warms and absorbs moisture from the land, creating persistent high-pressure systems that inhibit cloud formation and precipitation.

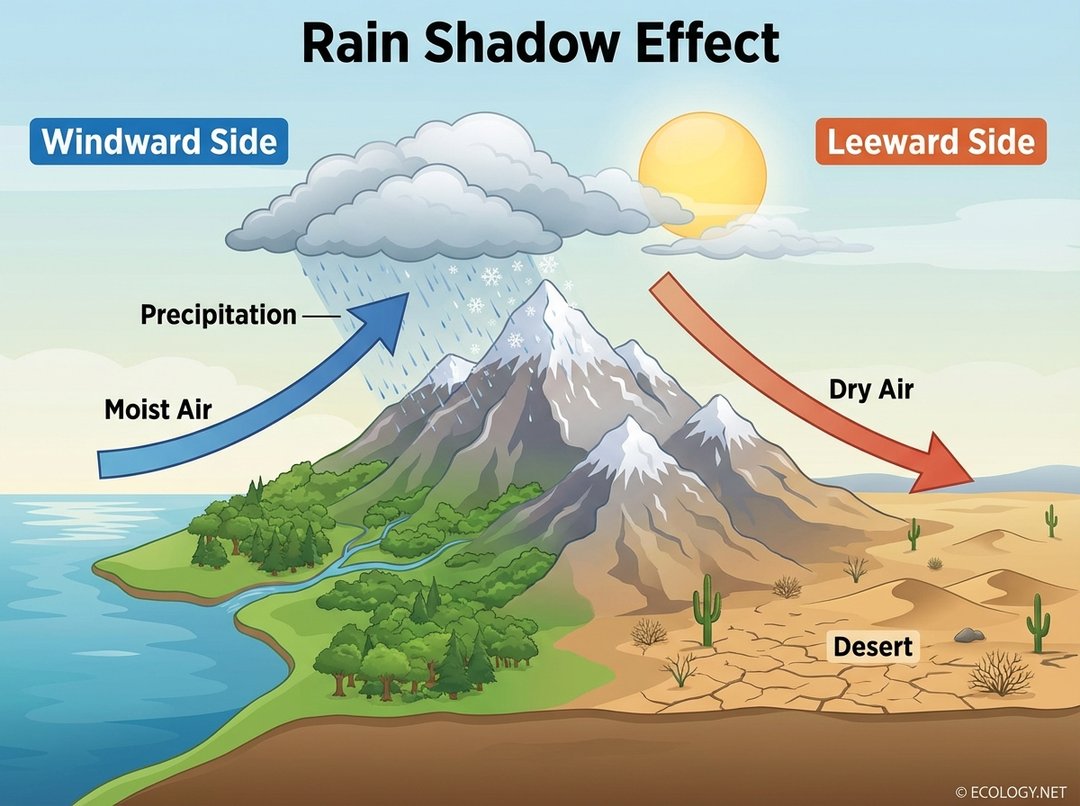

The Rain Shadow Effect

Mountain ranges play a significant role in creating deserts through what is known as the rain shadow effect. When moist air from an ocean encounters a mountain range, it is forced to rise. As the air ascends, it cools, and its moisture condenses, leading to precipitation on the windward side of the mountains. By the time the air crosses the mountain peaks and descends on the leeward side, it has lost most of its moisture, becoming dry and warm. This dry, descending air creates an arid zone, or “rain shadow,” on the leeward side.

A classic example of this phenomenon is the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California, which creates the vast arid landscapes of the Great Basin Desert to its east.

Continental Interiors

Deserts can also form deep within continents, far from any significant moisture source. By the time air masses travel thousands of kilometers inland from the coast, they have often lost much of their moisture, leading to arid conditions in the continental interior. The Gobi Desert in Central Asia is a prime example of a desert formed by its extreme distance from oceans.

Cold Ocean Currents

Along some coastlines, cold ocean currents flow parallel to the shore. These currents cool the air above them, creating stable atmospheric conditions that prevent the formation of rain-producing clouds. While fog may be common, it rarely translates into significant rainfall. The Atacama Desert in Chile, one of the driest places on Earth, and the Namib Desert in southwestern Africa are striking examples of deserts formed under the influence of cold ocean currents.

Life in the Drylands: Desert Biodiversity

Despite the harsh conditions, deserts are home to an astonishing array of life, showcasing some of nature’s most ingenious adaptations. Plants and animals in these environments have evolved specialized strategies to cope with extreme temperatures and, most importantly, the scarcity of water.

Plant Adaptations

Desert plants, known as xerophytes, employ various tactics to survive:

- Succulence: Many plants, like cacti and aloes, store water in their fleshy stems, leaves, or roots. Their thick, waxy cuticles minimize water loss through evaporation.

- Deep Roots: Some plants, such as mesquite trees, develop extensive root systems that can reach deep into the ground to tap into underground water sources.

- Ephemeral Life Cycles: “Annuals” or “ephemerals” rapidly sprout, flower, and produce seeds only after rare rainfall events, completing their entire life cycle in a matter of weeks before the moisture disappears.

- Reduced or Absent Leaves: To minimize transpiration (water loss through leaves), many desert plants have small leaves, thorns (which are modified leaves), or no leaves at all, relying on their stems for photosynthesis, like the ocotillo.

Animal Adaptations

Desert animals exhibit equally remarkable adaptations:

- Nocturnal Behavior: Many desert animals, including fennec foxes, kangaroo rats, and many reptiles, are active primarily at night when temperatures are cooler, avoiding the scorching daytime heat.

- Water Conservation:

- Some animals, like the kangaroo rat, can survive without drinking water, obtaining all necessary moisture from the seeds they eat. They also produce highly concentrated urine and dry feces to minimize water loss.

- Camels are famous for their ability to go long periods without water, thanks to their efficient kidneys, ability to tolerate significant dehydration, and specialized fat storage in their humps.

- Burrowing: Many small animals, insects, and reptiles escape extreme temperatures by burrowing underground, where temperatures are more stable.

- Specialized Diets: Some animals derive moisture from their prey, while others have evolved to consume specific, water-rich plants.

Types of Deserts

Beyond the hot and cold classification, deserts can be further categorized by their geographical location and the specific climatic forces that shaped them:

- Subtropical Deserts: These are the largest and hottest deserts, located around 30 degrees latitude north and south. Examples include the Sahara, Arabian, and Australian Deserts.

- Coastal Deserts: Formed by cold ocean currents, these deserts are often characterized by fog but very little rain. The Atacama Desert in Chile and the Namib Desert in Africa are prime examples.

- Rain Shadow Deserts: Created by mountain ranges blocking moisture, such as the Great Basin Desert in the western United States.

- Continental (Mid-latitude) Deserts: Found deep within continents, far from oceanic moisture. The Gobi Desert and the Taklamakan Desert in Asia are notable examples.

- Polar Deserts: While not always recognized in the traditional sense, the vast, icy expanses of the Arctic and Antarctic are technically deserts due to their extremely low precipitation and dry air.

The Importance of Deserts

Deserts are far more than just empty spaces; they are vital components of Earth’s global ecosystems:

- Unique Biodiversity: They harbor species found nowhere else, contributing significantly to global biodiversity.

- Scientific Laboratories: Their extreme conditions make them natural laboratories for studying adaptation, resilience, and even astrobiology, as some desert environments on Earth mimic conditions on other planets.

- Resource Richness: Deserts are often rich in mineral resources, including oil, natural gas, and various metals. They also hold immense potential for renewable energy, particularly solar power, due to abundant sunshine.

- Cultural Significance: Many ancient civilizations and indigenous cultures have thrived in desert environments, developing unique knowledge systems and ways of life adapted to these landscapes.

Challenges and Conservation

Despite their resilience, deserts face significant threats. Desertification, the process by which fertile land becomes desert, is a growing concern, often driven by climate change, deforestation, and unsustainable land use practices. Water scarcity, exacerbated by human demand and changing rainfall patterns, poses a critical challenge to both desert ecosystems and human communities. Conservation efforts focus on sustainable water management, protecting vulnerable species, combating desertification, and promoting responsible tourism to preserve these extraordinary environments for future generations.

Conclusion

Deserts are truly wonders of the natural world, defying expectations with their vibrant life and complex ecological processes. From the colossal forces that shape their arid landscapes to the intricate adaptations of their inhabitants, deserts offer endless lessons in resilience and survival. By understanding and appreciating these unique ecosystems, we can better work towards their conservation, ensuring that the silent majesty and extraordinary biodiversity of the drylands continue to inspire and educate for years to come.