Unlocking a Sustainable Future: A Deep Dive into the Circular Economy

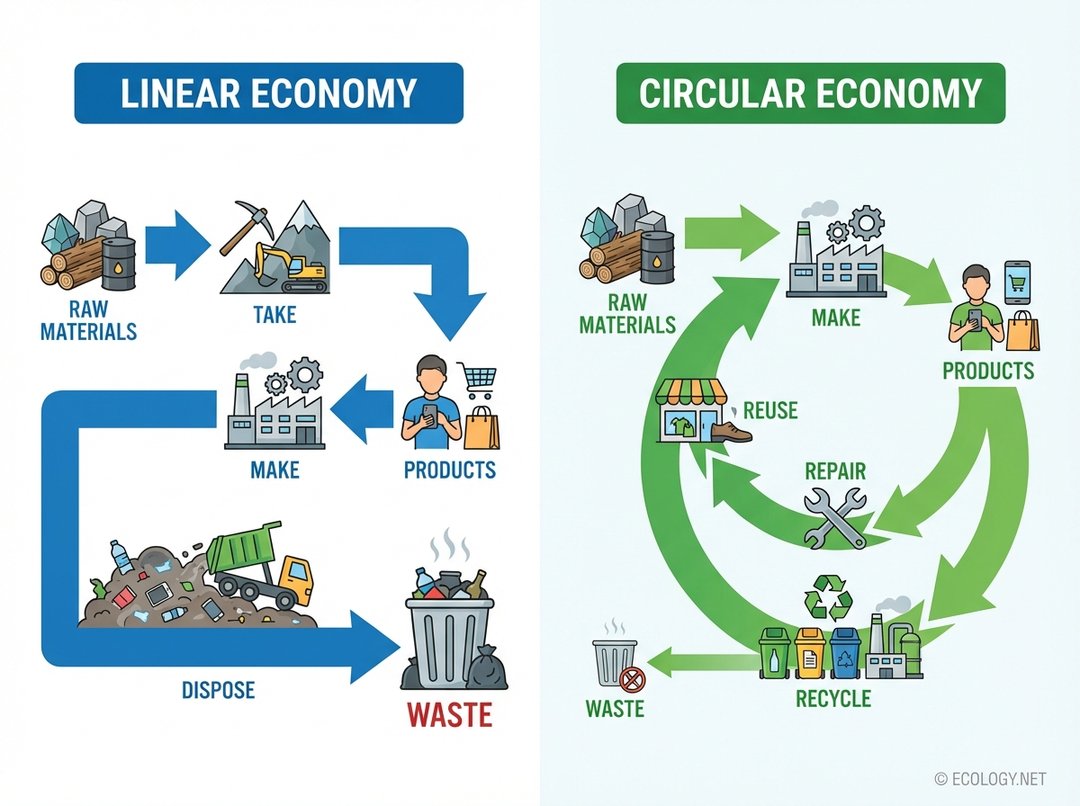

For centuries, humanity has operated on a simple, yet ultimately unsustainable, economic model: take, make, dispose. We extract raw materials, manufacture products, use them, and then discard them as waste. This linear approach has fueled industrial growth but has also led to alarming rates of resource depletion, pollution, and an ever-growing mountain of trash. But what if there was another way? What if we could design an economy that mimics nature itself, where waste is food, and resources are kept in continuous circulation? Welcome to the world of the circular economy, a revolutionary concept poised to redefine our relationship with materials, products, and the planet.

From Linear to Circular: A Fundamental Shift

To truly grasp the power of the circular economy, it is essential to understand what it seeks to replace. The traditional linear economy is a one-way street:

- Take: We extract virgin raw materials from the Earth, often through environmentally intensive processes like mining and logging.

- Make: These materials are then transformed into products in factories, consuming energy and often generating pollution.

- Dispose: After use, these products are typically thrown away, ending up in landfills or incinerators, where their valuable components are lost forever.

This model is inherently wasteful and unsustainable in a world with finite resources. It treats our planet as an endless quarry and a bottomless bin.

The circular economy, in stark contrast, envisions a system where products and materials are kept in use for as long as possible, extracting maximum value from them while in use, and then recovering and regenerating products and materials at the end of their service life. It is a closed-loop system designed to eliminate waste and pollution, circulate products and materials, and regenerate natural systems.

The Pillars of a Regenerative Future: Core Principles

The circular economy is not merely about recycling more. It is a holistic framework built upon three foundational principles, each designed to create a resilient and regenerative system:

- Design Out Waste and Pollution:

This principle is perhaps the most radical. Instead of managing waste after it is created, the circular economy advocates for designing products and systems in such a way that waste and pollution are never created in the first place. This means:

- Material Selection: Choosing non-toxic, durable, and renewable materials. For example, using biodegradable packaging instead of single-use plastics.

- Product Longevity: Designing products to be robust, easy to maintain, and long-lasting, like modular smartphones where components can be individually upgraded or replaced.

- Systemic Thinking: Considering the entire lifecycle of a product, from sourcing to end-of-life, to prevent negative impacts at every stage. Imagine a detergent bottle designed to be refilled at a local store, eliminating the need for a new bottle each time.

- Keep Products and Materials in Use:

Once a product is made, the goal is to keep it circulating in the economy for as long as possible. This principle emphasizes maximizing the utility of products and their components. Strategies include:

- Reuse: Directly using a product again for the same purpose, such as reusable coffee cups or refillable water bottles.

- Repair: Fixing broken items to extend their lifespan, like a local electronics repair shop bringing an old laptop back to life.

- Refurbish: Restoring an old product to a like-new condition, often seen with refurbished electronics or appliances.

- Remanufacture: Disassembling products, cleaning and inspecting components, and then reassembling them into new products, common in industries like automotive parts.

- Sharing and Leasing Models: Shifting from ownership to access, where products like tools, cars, or even clothing are shared or leased, ensuring they are used more intensively. Think of a tool library or a clothing rental service.

- Regenerate Natural Systems:

Beyond minimizing harm, the circular economy aims to actively improve and restore natural environments. This principle focuses on returning biological materials to the earth safely and enhancing ecosystems. Examples include:

- Composting and Anaerobic Digestion: Returning organic waste, like food scraps and garden clippings, to the soil to enrich it and sequester carbon.

- Sustainable Agriculture: Practices that build soil health, increase biodiversity, and reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

- Renewable Energy: Powering economic activities with solar, wind, and other renewable sources to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and minimize pollution.

- Water Stewardship: Designing systems that conserve water, treat wastewater effectively, and replenish freshwater sources.

Beyond Recycling: The Hierarchy of Circular Strategies

When many people first hear about the circular economy, their minds often jump straight to recycling. While recycling is an important component, it is far from the only, or even the most effective, strategy. The circular economy operates on a hierarchy of interventions, often visualized as a series of “R’s,” where some actions are significantly more impactful than others in preserving value and reducing environmental footprint.

Understanding this hierarchy is crucial for truly embracing circularity:

- Refuse: This is the most powerful “R.” It means saying “no” to products or practices that are inherently wasteful or harmful. For instance, refusing single-use plastic bags, straws, or excessive packaging. It is about preventing waste at its source by not consuming it in the first place.

- Reduce: Minimizing the amount of resources consumed and waste generated. This could involve buying less, choosing smaller portions, or opting for products with minimal packaging. For example, buying concentrated cleaning products or choosing digital subscriptions over physical magazines.

- Reuse: Using a product multiple times for its original purpose. Think of bringing your own reusable shopping bags, water bottles, or coffee cups. This extends the life of an item without significant processing.

- Repair: Fixing broken items instead of replacing them. This could be mending clothes, repairing electronics, or patching up furniture. It requires access to spare parts and skilled labor, fostering local economies.

- Refurbish: Restoring a used product to a good working condition, often involving cleaning, minor repairs, and aesthetic improvements. Refurbished smartphones or appliances are common examples, offering a more affordable and sustainable alternative to new purchases.

- Remanufacture: Taking a used product, disassembling it, inspecting and replacing worn components, and then reassembling it to meet original specifications. This is more intensive than refurbishing and is prevalent in industries like automotive parts, industrial machinery, and office furniture.

- Repurpose: Using an item for a different function than its original intent. An old tire becoming a planter, or glass jars becoming storage containers, are simple examples. This creative approach gives new life to items that might otherwise be discarded.

- Recycle: Processing waste materials to create new products. While vital, recycling is typically the last resort in the circular hierarchy because it often requires significant energy and can degrade material quality over time. For example, plastic bottles being recycled into new plastic products, or aluminum cans being melted down and reformed.

By prioritizing the higher-level strategies, we can significantly reduce our environmental footprint and maximize resource value.

The Multifaceted Benefits of Embracing Circularity

The shift to a circular economy offers a cascade of benefits that extend far beyond environmental protection:

Environmental Benefits:

- Reduced Waste and Pollution: By designing out waste and keeping materials in circulation, the volume of landfill waste and the release of pollutants into air and water are drastically cut.

- Resource Conservation: Less reliance on virgin raw materials means preserving natural habitats, reducing biodiversity loss, and mitigating the impacts of extraction industries.

- Climate Change Mitigation: A circular economy can significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions by reducing energy-intensive production of new materials, extending product lifespans, and regenerating natural carbon sinks.

- Ecosystem Restoration: The principle of regenerating natural systems actively works to heal degraded environments, improve soil health, and enhance biodiversity.

Economic Benefits:

- New Business Models and Innovation: The circular economy fosters innovation in product design, service models (like product-as-a-service), and reverse logistics, creating new markets and opportunities.

- Job Creation: New jobs emerge in areas like repair, remanufacturing, collection, and material processing, often localized and skilled.

- Cost Savings: Businesses can reduce material costs by reusing components, sourcing recycled content, and optimizing resource use. Consumers can save money through repair, rental, and second-hand markets.

- Increased Resource Security: By reducing dependence on volatile global supply chains for virgin materials, countries and companies can enhance their resilience to resource price fluctuations and scarcity.

Social Benefits:

- Improved Public Health: Less pollution from extraction and manufacturing processes leads to cleaner air and water, benefiting community health.

- Enhanced Community Resilience: Localized circular models can strengthen communities through local repair services, sharing initiatives, and robust local economies.

- Empowered Consumers: Consumers gain more choices for sustainable consumption, access to durable and repairable products, and opportunities to participate in a more responsible economy.

Implementing the Circular Economy: Practical Examples and Applications

The circular economy is not just a theoretical concept; it is being put into practice across various sectors, demonstrating its versatility and potential:

- Fashion Industry:

- Rental and Resale Platforms: Companies offering clothing rental services or platforms for buying and selling pre-owned garments, extending the life of fashion items.

- Design for Longevity and Repair: Brands creating durable clothing with timeless designs and offering repair services or guides.

- Material Innovation: Developing textiles from recycled content or biodegradable materials, and exploring closed-loop textile recycling.

- Electronics Sector:

- Modular Design: Laptops and smartphones designed with easily replaceable components, allowing users to upgrade or repair parts instead of buying a whole new device.

- Take-Back Programs: Manufacturers offering to collect old electronics for refurbishment, remanufacturing, or responsible recycling.

- Product-as-a-Service: Businesses leasing electronics to customers, maintaining them throughout their lifecycle, and then recovering them at the end for reuse or remanufacturing.

- Food Systems:

- Food Waste Reduction: Initiatives to minimize food loss from farm to fork, including better storage, redistribution of surplus food, and consumer education.

- Composting and Anaerobic Digestion: Converting unavoidable food waste into nutrient-rich compost or biogas, regenerating soil and producing renewable energy.

- Valorizing By-products: Turning what was once considered waste, like fruit peels or coffee grounds, into new valuable products such as ingredients, textiles, or biofuels.

- Construction and Built Environment:

- Designing for Disassembly: Buildings constructed with materials and components that can be easily deconstructed and reused at the end of the building’s life.

- Material Banks: Creating inventories of reusable building materials from demolition sites for new construction projects.

- Recycled Content: Using recycled concrete, steel, and other materials in new building projects.

Challenges and the Path Forward

While the vision of a circular economy is compelling, the transition from a deeply entrenched linear system presents significant challenges:

- Infrastructure Gaps: Building the necessary collection, sorting, repair, remanufacturing, and recycling infrastructure requires substantial investment.

- Consumer Behavior: Shifting consumer mindsets from ownership to access, and from disposable to durable, requires education and convenience.

- Policy and Regulation: Governments need to create supportive policies, incentives, and regulations that favor circular practices and discourage linear ones.

- Business Model Innovation: Companies must rethink their entire value chains, moving away from selling products to providing services or ensuring product longevity.

- Material Complexity: The increasing complexity of products with mixed materials can make disassembly, repair, and recycling more challenging.

Overcoming these hurdles requires a concerted effort from individuals, businesses, and governments. Individuals can make conscious purchasing decisions, support circular businesses, and embrace repair and reuse. Businesses can innovate in design, develop circular business models, and collaborate across supply chains. Governments can set ambitious targets, provide financial incentives, and establish clear regulatory frameworks.

A Circular Horizon: Our Collective Future

The circular economy offers a powerful and optimistic vision for the future. It is not merely an environmental strategy but a comprehensive economic framework that promises greater resource security, economic resilience, and social equity. By redesigning our systems to eliminate waste, keep products and materials in use, and regenerate natural systems, we can move beyond the limitations of the linear model and build an economy that thrives in harmony with our planet. The journey to a truly circular world is complex, but the destination is a sustainable and prosperous future for all.