Unveiling the World of Browsers: Nature’s Arboreal Architects

In the intricate tapestry of Earth’s ecosystems, life thrives through countless interactions, none more fundamental than how organisms acquire their sustenance. Among the vast array of feeding strategies, one group stands out for its unique approach to dining: the browsers. Far from mere eaters, browsers are pivotal forces that sculpt landscapes, influence plant evolution, and drive nutrient cycles. Understanding these fascinating creatures offers a profound glimpse into the delicate balance and dynamic nature of our planet’s biodiversity.

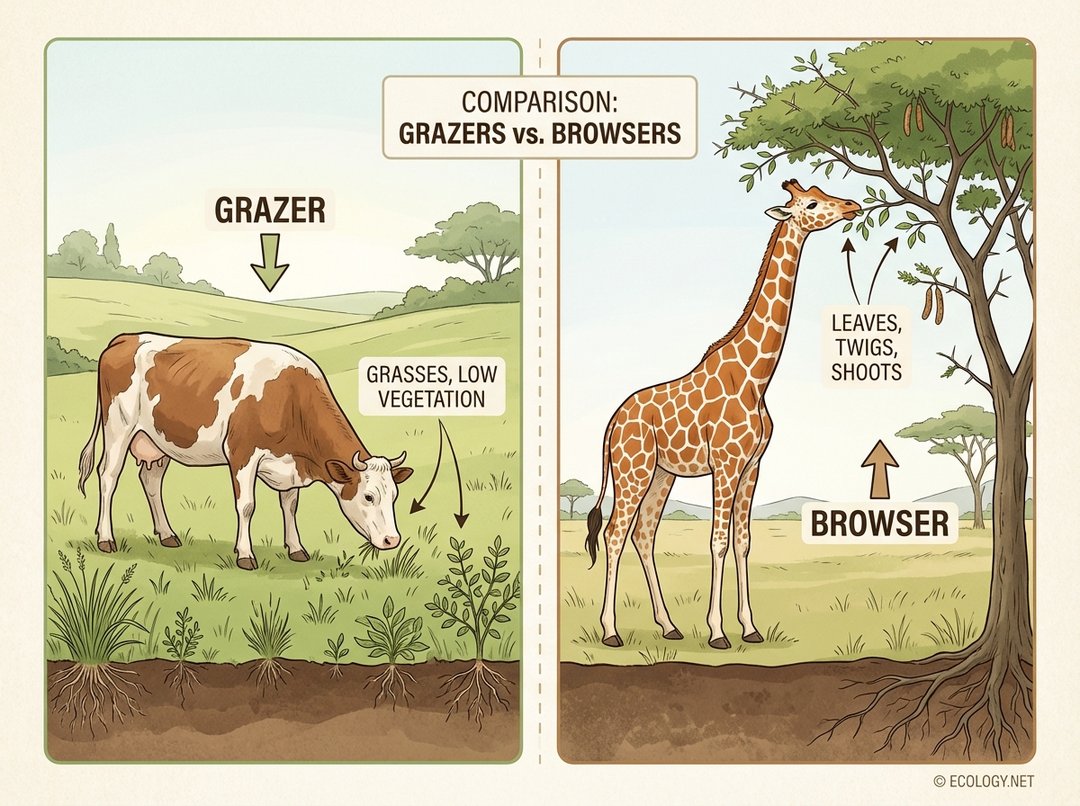

Browsers vs. Grazers: A Fundamental Distinction

To truly appreciate browsers, it is essential to first distinguish them from their close ecological relatives, the grazers. Both are herbivores, meaning they consume plant material, but their dietary preferences and feeding behaviors set them distinctly apart.

Grazers primarily feed on grasses and other low-lying vegetation. Think of a cow contentedly munching in a pasture, or a zebra sweeping across the savanna. Their mouths and digestive systems are typically adapted to process fibrous, often silica-rich grasses.

Browsers, on the other hand, specialize in consuming leaves, twigs, bark, and shoots from shrubs, trees, and other woody or tall herbaceous plants. They reach upwards, often selecting specific parts of plants rather than indiscriminately cropping large swathes of vegetation.

This fundamental difference in diet dictates everything from their physical adaptations to their ecological impact.

The Diverse World of the Browsing Guild

The term “browser” encompasses an astonishing array of species, ranging from the colossal to the microscopic. This diversity underscores the widespread success of this feeding strategy across various biomes and taxonomic groups.

Mammalian Browsers

- Large Mammals: Perhaps the most iconic browsers are large mammals.

- Giraffes are quintessential browsers, using their immense height and long necks to reach leaves high in acacia trees.

- Elephants are highly versatile, browsing on leaves, bark, and branches, often dramatically altering forest structure.

- Deer species, such as white-tailed deer and moose, are common browsers in temperate forests, feeding on twigs, buds, and leaves of shrubs and young trees.

- Goats are well-known domestic browsers, capable of consuming a wide variety of woody plants.

- Rhinoceroses, particularly black rhinos, are also dedicated browsers, using their prehenshensile upper lip to grasp branches.

- Smaller Mammals: Even smaller mammals contribute significantly to browsing.

- Rabbits and hares browse on young shoots and bark, especially in winter.

- Koalas are highly specialized browsers, feeding almost exclusively on eucalyptus leaves.

Insect and Invertebrate Browsers

The browsing guild extends far beyond mammals, with countless invertebrates playing crucial roles.

- Caterpillars are voracious browsers, consuming leaves and often defoliating entire plants.

- Beetles, particularly many species of leaf beetles, feed on plant foliage.

- Snails and slugs browse on tender leaves and plant tissues, leaving characteristic trails.

- Stick insects are masters of camouflage while they slowly browse on leaves.

This incredible diversity highlights that browsing is not merely a feeding habit but a fundamental ecological niche occupied by life forms of all sizes and complexities.

Adaptations for a Browsing Lifestyle

The specialized diet of browsers has led to a fascinating array of evolutionary adaptations, allowing them to efficiently locate, consume, and digest their chosen plant material.

Dental and Oral Adaptations

- Prehensile Lips and Tongues: Many browsers possess highly mobile lips or tongues, which act like nimble fingers to grasp and strip leaves from branches. Giraffes and black rhinos are prime examples.

- Specialized Teeth: Unlike grazers with broad, flat molars for grinding tough grasses, browsers often have narrower molars and sometimes specialized incisors for nipping off shoots and leaves. Some also have strong canines or incisors for stripping bark.

Digestive Systems

Plant material, especially woody parts, can be difficult to digest. Browsers have evolved sophisticated digestive systems to extract nutrients.

- Ruminants: Many mammalian browsers, such as deer and giraffes, are ruminants. They possess a four-chambered stomach that allows for fermentation of plant material by microbes, breaking down cellulose and extracting maximum nutrients. This process involves regurgitation and re-chewing (cud chewing).

- Hindgut Fermenters: Other browsers, like elephants, are hindgut fermenters. Their fermentation occurs in the large intestine and cecum. While less efficient at nutrient extraction than rumination, this system allows for faster processing of large volumes of food.

- Enzymatic Adaptations: Some insect browsers have specialized enzymes in their gut to neutralize plant toxins or break down specific compounds.

Sensory and Behavioral Adaptations

- Acute Sense of Smell: Browsers often rely on a keen sense of smell to detect palatable plants, identify nutrient-rich parts, and avoid toxic species.

- Selective Feeding: Browsers are often highly selective, choosing specific plant species, particular leaves, or even certain parts of a leaf. This selectivity can be driven by nutrient content, water availability, or the presence of defensive compounds.

- Tolerance to Plant Defenses: Plants have evolved various defenses against browsing, including thorns, tough leaves, and chemical toxins. Browsers, in turn, have developed mechanisms to cope, such as thick mouth linings, detoxification enzymes, or behavioral strategies to avoid highly defended plants.

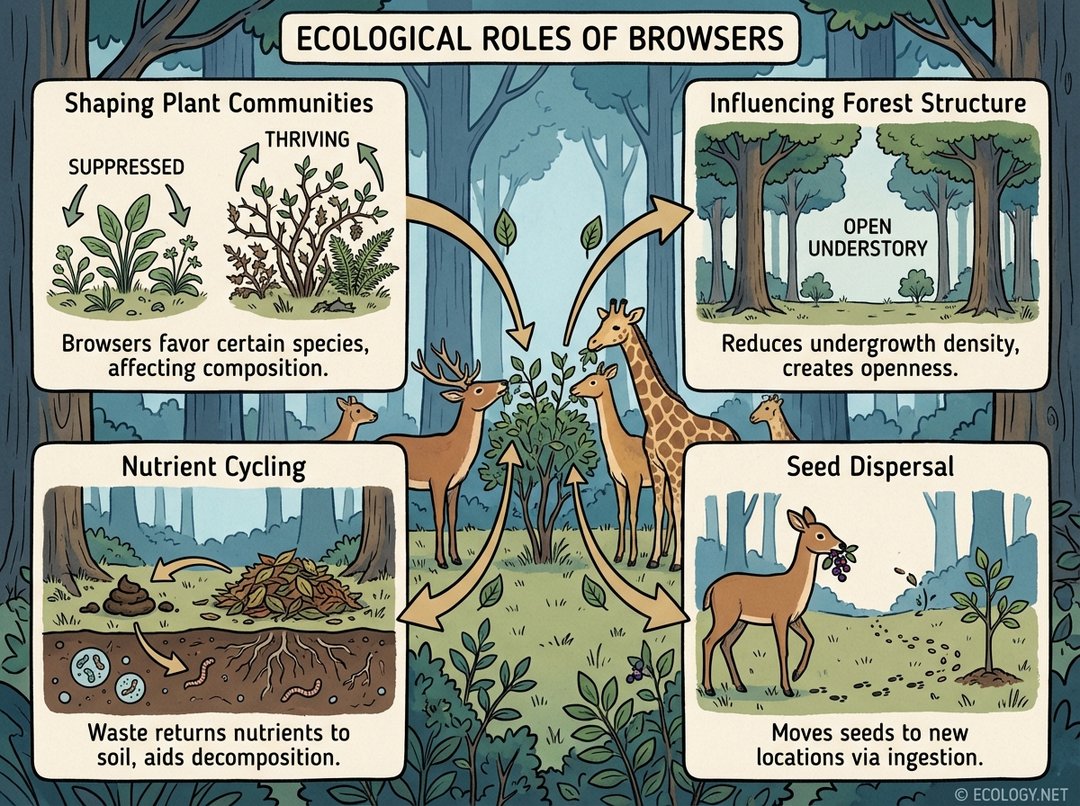

The Ecological Roles of Browsers: Shaping Ecosystems

Browsers are not passive consumers; they are active agents of change, profoundly influencing the structure, composition, and health of the ecosystems they inhabit. Their impact ripples through multiple trophic levels and ecological processes.

Shaping Plant Communities

By selectively feeding on certain plant species, browsers can:

- Alter Species Composition: They can suppress the growth of preferred species, allowing less palatable or more resistant plants to thrive. This can lead to shifts in the dominant plant types within an area.

- Promote Plant Diversity: In some cases, moderate browsing can prevent a few dominant plant species from outcompeting others, thereby increasing overall plant diversity.

- Influence Plant Evolution: The constant pressure from browsing drives the evolution of plant defenses, such as thorns, chemical toxins, and rapid regrowth strategies. This co-evolutionary arms race is a powerful force in nature.

Influencing Forest Structure

Browsers play a critical role in determining the physical architecture of forests and woodlands.

- Creating Open Understories: Heavy browsing can remove young trees and shrubs, leading to a more open understory layer in forests.

- Promoting Shrublands: In some environments, browsing can prevent the establishment of trees, maintaining areas as shrublands or savannas.

- “Browse Lines”: The distinct horizontal line visible on trees and shrubs, below which all foliage has been consumed, is a clear indicator of browsing pressure.

Nutrient Cycling

Browsers are integral to the movement of nutrients within an ecosystem.

- Decomposition: By consuming plant material, they convert plant biomass into waste products (feces and urine) that return nutrients to the soil in a more readily available form for other organisms and plants.

- Distribution of Nutrients: Browsers move nutrients across the landscape as they feed and excrete, influencing soil fertility in different areas.

Seed Dispersal

Many browsers inadvertently act as seed dispersers, a vital ecological service.

- Endozoochory: Seeds consumed along with plant material can pass through the digestive tract unharmed and be deposited in new locations, often with a ready supply of fertilizer (the animal’s waste). This is particularly important for plants with tough seed coats that benefit from scarification during digestion.

- Epizoochory: Some seeds may also attach to the fur or skin of browsers and be carried to new areas.

Challenges and Conservation of Browsers

Despite their ecological importance, browser populations worldwide face numerous threats, often linked to human activities.

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: The conversion of forests and shrublands for agriculture, urban development, and infrastructure directly reduces the available browsing habitat.

- Over-browsing: In areas where browser populations become too high due to a lack of predators or human intervention, they can exert excessive pressure on vegetation, leading to degradation of plant communities and reduced biodiversity. This can be a significant management challenge in protected areas.

- Climate Change: Shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns can alter plant growth, distribution, and palatability, impacting browser food sources.

- Poaching and Hunting: Illegal hunting and unsustainable hunting practices threaten many large browser species, such as elephants and rhinos.

Conservation efforts for browsers often involve habitat protection and restoration, sustainable land management practices, and population management strategies to maintain a healthy balance between browser numbers and vegetation health. Understanding the specific dietary needs and ecological roles of different browser species is crucial for effective conservation.

Conclusion: The Unsung Heroes of the Canopy and Shrubland

From the towering giraffe delicately plucking leaves to the humble caterpillar munching its way across a single blade, browsers are a diverse and indispensable component of nearly every terrestrial ecosystem. They are not just consumers; they are architects, engineers, and gardeners of the natural world, constantly shaping the environment through their feeding habits. Their adaptations are marvels of evolution, and their ecological roles are profound, influencing plant communities, nutrient cycles, and the very structure of forests. As we continue to navigate a changing world, recognizing and conserving these remarkable creatures is paramount to maintaining the health and resilience of our planet’s rich biodiversity.