Imagine a tiny fish swimming in a seemingly clean stream. Over its lifetime, this fish might encounter various substances in its environment. Some of these substances, particularly certain pollutants, have a sneaky way of accumulating within the fish’s body, building up over time rather than being easily expelled. This fascinating and often concerning process is known as bioaccumulation.

Bioaccumulation is a fundamental concept in environmental science and ecology, explaining how chemicals can enter and persist within living organisms. It is a critical mechanism that can lead to significant ecological and health impacts, even when environmental concentrations of a pollutant appear low.

Understanding Bioaccumulation: A Closer Look

At its core, bioaccumulation describes the net uptake of a substance by an organism from all environmental sources, including water, food, and air, leading to a higher concentration of that substance in the organism than in its surrounding environment. This buildup occurs when the rate of uptake exceeds the rate of excretion or metabolism.

Bioaccumulation vs. Biomagnification: A Key Distinction

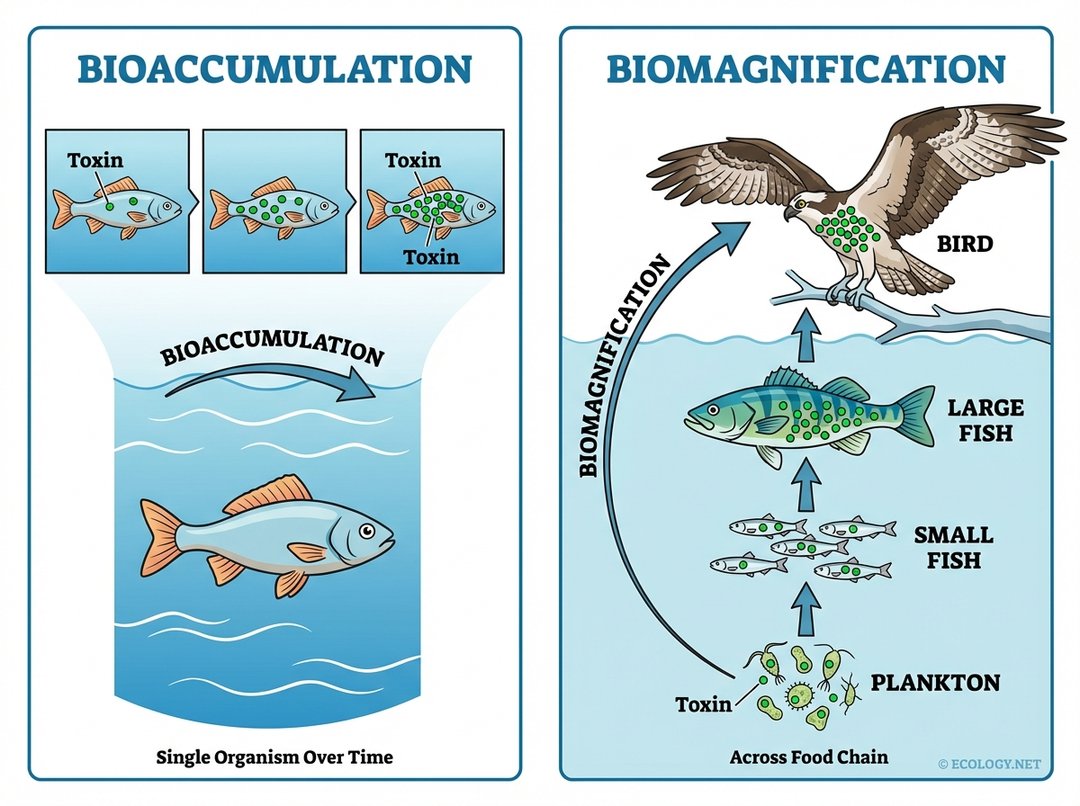

While often used interchangeably, bioaccumulation and biomagnification are distinct processes, though closely related. Understanding the difference is crucial for grasping how pollutants move through ecosystems.

Bioaccumulation, as we have discussed, refers to the increase in concentration of a substance in an organism over its lifetime. Think of a single fish gradually accumulating a toxin in its tissues from the water it swims in and the food it eats. The concentration within that individual fish increases with time.

Biomagnification, on the other hand, describes the increasing concentration of a substance in the tissues of organisms at successively higher levels in a food chain. This means that as you move up the food chain, from plankton to small fish, to large fish, and then to a predatory bird, the concentration of the toxin becomes progressively higher at each trophic level. Biomagnification is essentially bioaccumulation occurring across an entire food web, leading to apex predators having the highest concentrations.

Bioaccumulation is about an individual organism’s internal buildup, while biomagnification is about the escalating concentration of toxins across an entire food chain.

How Does Bioaccumulation Happen? Pathways and Properties

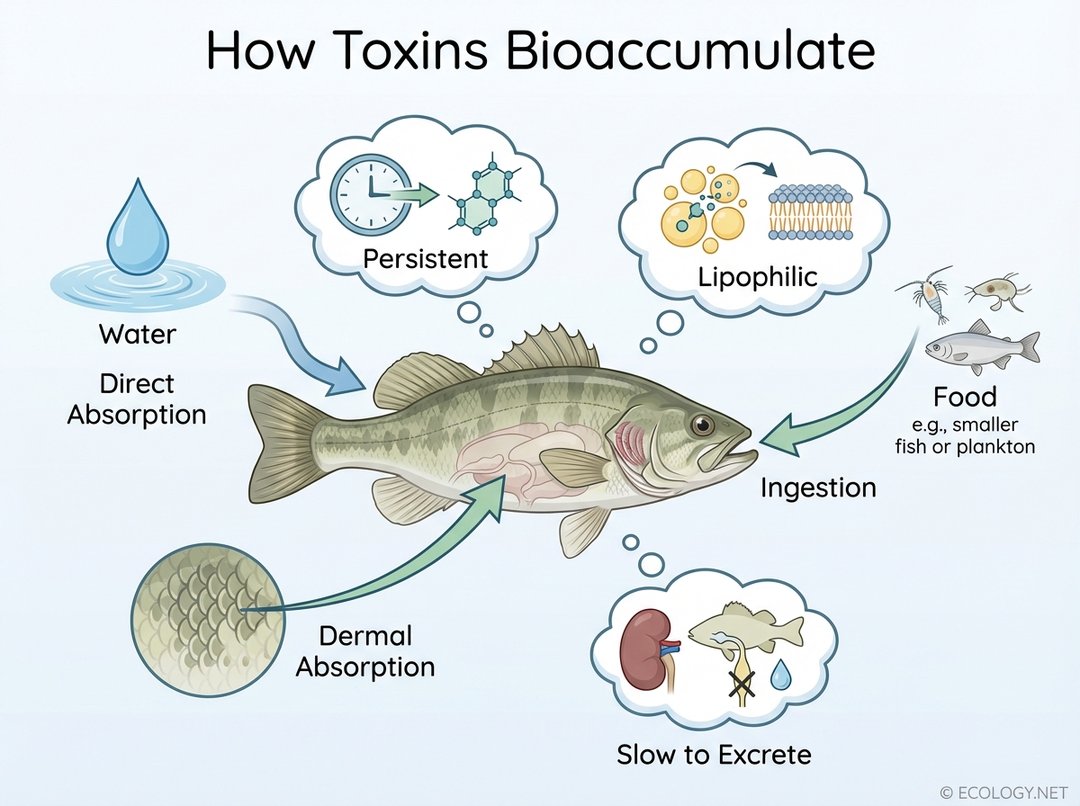

For a substance to bioaccumulate, it must enter an organism and then persist within its tissues. Several pathways facilitate this entry, and certain properties of the substance itself make it more prone to accumulation.

Pathways of Absorption

- Direct Absorption: Many aquatic organisms, like fish, can absorb substances directly from the surrounding water through their gills or skin. The concentration of the pollutant in the water directly influences the rate of uptake.

- Ingestion: This is a primary route for most organisms. When an animal consumes contaminated food, the toxins present in that food are absorbed into its body. For example, a fish eating contaminated plankton will ingest the toxins accumulated by the plankton.

- Dermal Absorption: While less common for aquatic organisms in terms of significant pollutant uptake compared to gills or ingestion, some substances can be absorbed through the skin, particularly in terrestrial animals or those with permeable skin.

Key Properties of Bioaccumulating Substances

Not all substances bioaccumulate equally. Those that pose the greatest risk typically share a few critical characteristics:

- Persistent: These substances do not easily break down in the environment or within an organism’s body. They resist degradation by biological, chemical, or photolytic processes, meaning they remain intact for long periods. Examples include certain pesticides and industrial chemicals.

- Lipophilic (Fat-Soluble): Many bioaccumulating toxins are highly soluble in fats and oils, rather than water. This property allows them to readily cross biological membranes (which are lipid-based) and accumulate in fatty tissues of organisms. Once stored in fat, they are difficult for the body to excrete.

- Slow to Excrete: Organisms have mechanisms to metabolize and excrete waste products. However, substances that bioaccumulate are often difficult for the body to process and eliminate efficiently. Their excretion rate is significantly slower than their uptake rate, leading to a net increase in concentration over time.

The Impact of Bioaccumulation: Why It Matters

The consequences of bioaccumulation extend far beyond individual organisms. It has profound implications for ecosystem health and human well-being.

Ecological Impacts

- Individual Organism Health: High concentrations of toxins can impair an organism’s physiological functions, leading to reproductive problems, developmental abnormalities, immune system suppression, behavioral changes, and even death. For example, birds exposed to high levels of DDT experienced eggshell thinning, leading to reproductive failure.

- Population and Ecosystem Effects: When individual organisms are affected, entire populations can decline. This can disrupt food webs, alter species composition, and reduce biodiversity. Apex predators are particularly vulnerable due to biomagnification, making them indicators of ecosystem health.

Human Health Impacts

Humans are often at the top of many food chains, making us susceptible to the effects of biomagnified toxins. Consuming contaminated seafood, meat, or produce can lead to the accumulation of these substances in our own bodies.

- Neurological Damage: Heavy metals like mercury are notorious for causing neurological problems, affecting brain development in children and cognitive function in adults.

- Reproductive Issues: Some persistent organic pollutants (POPs) can act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormonal systems and leading to reproductive and developmental problems.

- Cancer: Certain bioaccumulating chemicals are known carcinogens, increasing the risk of various cancers.

- Immune System Suppression: Exposure to some toxins can weaken the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to diseases.

Real-World Examples of Bioaccumulation

To truly appreciate the significance of bioaccumulation, it helps to look at concrete examples that have shaped our understanding of environmental toxicology.

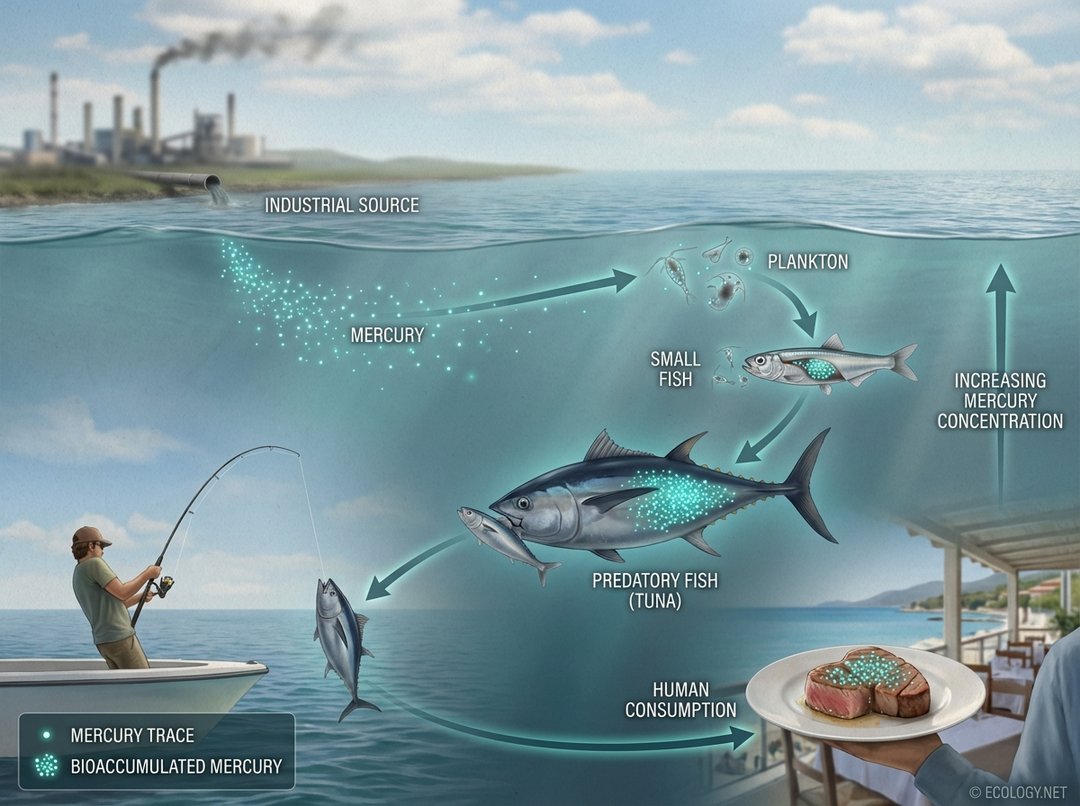

Mercury in Aquatic Food Webs

One of the most well-known examples of bioaccumulation and biomagnification involves mercury. Mercury is released into the environment from natural sources (like volcanoes) and human activities (such as coal combustion and gold mining). In aquatic environments, bacteria can convert inorganic mercury into methylmercury, a highly toxic and bioaccumulative form.

- Tiny aquatic organisms, like plankton, absorb small amounts of methylmercury from the water.

- Small fish eat many contaminated plankton, accumulating higher concentrations of mercury.

- Larger predatory fish, such as tuna, swordfish, and shark, consume numerous small fish, leading to significantly elevated mercury levels in their tissues.

- When humans consume these large predatory fish, they ingest the accumulated mercury, which can then build up in their bodies, posing risks, especially to pregnant women and young children.

DDT and its Legacy

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, is a synthetic pesticide that was widely used in the mid-20th century. While effective at controlling insect pests and disease vectors like mosquitoes, its persistent and lipophilic nature led to widespread environmental contamination. DDT bioaccumulated in insects, then biomagnified up the food chain, causing devastating effects on bird populations, particularly raptors like bald eagles and peregrine falcons. The thinning of their eggshells, a direct result of DDT exposure, led to reproductive failure and dramatic population declines. The global ban on DDT’s agricultural use is a testament to the severe consequences of bioaccumulation.

Factors Influencing Bioaccumulation: A Deeper Dive

Beyond the inherent properties of a substance, several other factors can influence the extent to which a chemical bioaccumulates in an organism.

Environmental Factors

- Temperature: Higher temperatures can increase an organism’s metabolic rate, potentially affecting both uptake and excretion rates.

- pH: The acidity or alkalinity of water can alter the chemical form of a pollutant, influencing its bioavailability and how readily it is absorbed.

- Salinity: In aquatic environments, salinity can affect the physiological stress on organisms, which in turn can impact their ability to process and excrete toxins.

- Sediment Composition: Pollutants can bind to sediments, making them less available for uptake by some organisms, but potentially more available to bottom-dwelling species.

Organismal Factors

- Species: Different species have varying metabolic capacities, diets, and life spans, all of which influence bioaccumulation. For example, a long-lived species will have more time to accumulate toxins.

- Age and Size: Older and larger organisms generally have had more time to accumulate substances, often showing higher concentrations than younger, smaller individuals of the same species.

- Lipid Content: Organisms with higher fat content tend to accumulate more lipophilic substances, as these toxins readily dissolve and store in fatty tissues.

- Metabolic Rate: An organism’s metabolic rate affects how quickly it can process and potentially excrete toxins.

Chemical Properties Revisited

While mentioned earlier, it is worth emphasizing specific chemical properties that scientists use to predict bioaccumulation potential:

- Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient (Kow): This value indicates how a chemical distributes between octanol (a lipid-like solvent) and water. A high Kow suggests high lipophilicity and a greater tendency to bioaccumulate.

- Bioconcentration Factor (BCF): This is a ratio of the concentration of a chemical in an organism to its concentration in the surrounding water. A high BCF indicates significant uptake directly from water.

- Biomagnification Factor (BMF): This ratio compares the concentration of a chemical in a predator to its concentration in its prey. A BMF greater than 1 indicates biomagnification.

- Half-Life: The environmental and biological half-life of a substance, which is the time it takes for half of the substance to degrade or be eliminated, is a direct measure of its persistence.

Mitigating the Risks of Bioaccumulation

Addressing bioaccumulation requires a multi-faceted approach, from policy and industry changes to individual consumer choices.

- Source Reduction: The most effective strategy is to prevent the release of persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic (PBT) substances into the environment in the first place. This involves developing safer alternatives, improving industrial processes, and responsible waste management.

- Regulation and Monitoring: Governments play a crucial role in regulating the production and release of hazardous chemicals, setting environmental quality standards, and monitoring pollutant levels in ecosystems and food sources.

- Consumer Awareness and Education: Informed consumers can make choices that reduce their exposure to bioaccumulating toxins. This includes understanding fish consumption advisories, choosing sustainably sourced products, and being aware of chemicals in household products.

- Remediation: In some cases, efforts can be made to clean up contaminated sites, though this is often challenging and costly, especially for widespread pollutants.

Conclusion: A Call for Awareness

Bioaccumulation is a powerful ecological process with far-reaching implications. It reminds us that our actions, even seemingly small ones, can have lasting impacts on the environment and our own health. From the microscopic plankton to the apex predator, and ultimately to humans, the intricate web of life is interconnected, and the fate of pollutants within it affects us all.

By understanding the mechanisms of bioaccumulation, the properties of concerning substances, and the pathways through which they enter our ecosystems and bodies, we can make more informed decisions. This knowledge empowers us to advocate for cleaner environments, support sustainable practices, and protect the delicate balance of life on Earth for generations to come.