The Incredible World of Adaptation: How Life Thrives Against All Odds

Life on Earth is a testament to resilience and ingenuity. From the scorching deserts to the frigid poles, from the deepest oceans to the highest mountains, organisms have found remarkable ways to survive and flourish. This incredible ability to adjust and thrive in diverse environments is known as adaptation. It is the cornerstone of evolution, a continuous process that shapes every living thing on our planet, allowing species to overcome challenges and exploit opportunities in their surroundings. Understanding adaptation unlocks a deeper appreciation for the intricate web of life and the powerful forces that drive its diversity.

What Exactly is Adaptation?

At its core, adaptation refers to a heritable trait or characteristic that increases an organism’s fitness, meaning its ability to survive and reproduce in a specific environment. These traits are not developed by an individual during its lifetime in response to a need. Instead, they arise through random genetic mutations over countless generations and are then favored by natural selection if they provide a survival advantage. Think of it as nature’s long-term design process, constantly refining species to better fit their ecological niches.

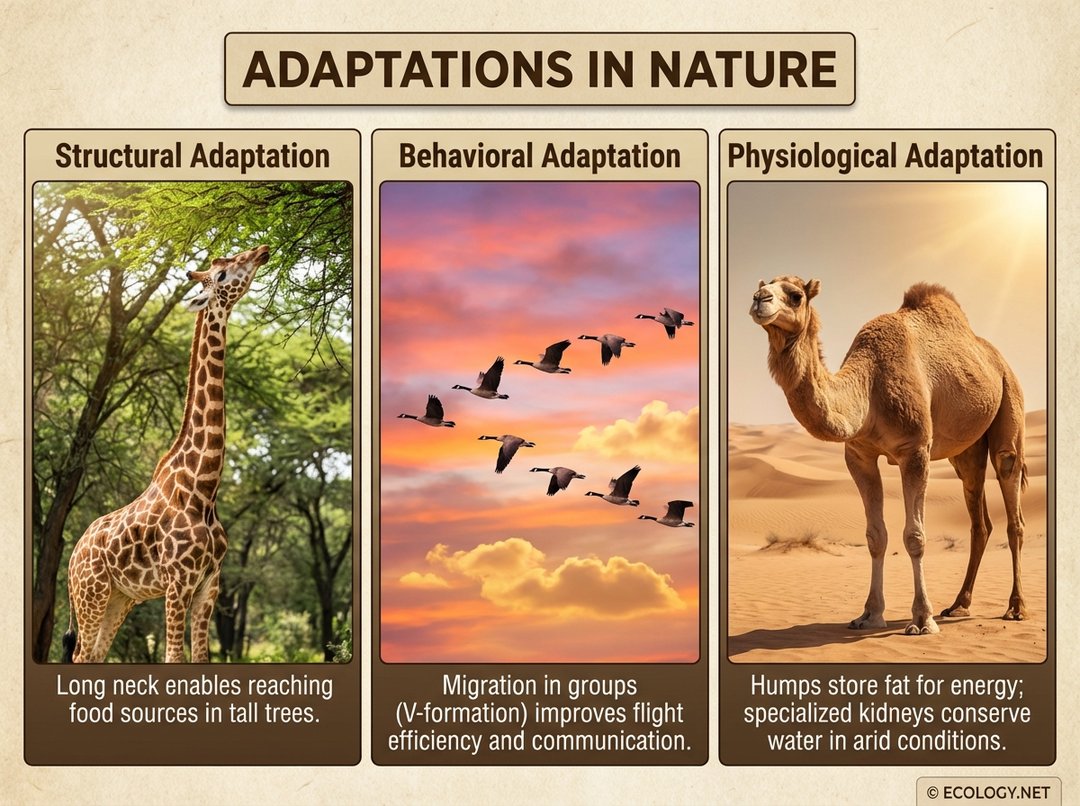

The Three Main Types of Adaptation

Adaptations manifest in a myriad of ways, but they can generally be categorized into three primary types: structural, behavioral, and physiological. Each type plays a crucial role in an organism’s survival strategy.

Structural Adaptations

These are physical features of an organism’s body that help it survive. They are often the most visible and easily recognizable forms of adaptation.

- Camouflage: The ability to blend in with the surroundings, like a chameleon changing its skin color or a polar bear’s white fur in the snow. This helps organisms avoid predators or ambush prey.

- Mimicry: When one species evolves to resemble another, often a more dangerous or unpalatable one. The harmless viceroy butterfly mimicking the toxic monarch butterfly is a classic example.

- Specialized Limbs: The long neck of a giraffe allows it to reach high leaves, while the powerful legs of a kangaroo are perfect for hopping across vast distances.

- Protective Coverings: The thick shell of a turtle, the spines of a porcupine, or the bark of a tree all serve as defenses against external threats.

Behavioral Adaptations

These are actions or patterns of activity that an organism performs to survive. They involve how an organism interacts with its environment and other organisms.

- Migration: The seasonal movement of animals from one region to another in search of food, mates, or more favorable climates, such as birds flying south for the winter.

- Hibernation: A state of inactivity and metabolic depression in endotherms, characterized by lower body temperature, slower breathing, and lower metabolic rate, allowing animals like bears to survive harsh winters.

- Nocturnal Activity: Many desert animals are active at night to avoid the extreme heat of the day.

- Social Behavior: Living in groups, like a pack of wolves hunting together or a colony of ants cooperating, can provide protection, aid in foraging, or improve reproductive success.

- Courtship Rituals: Elaborate dances or displays performed by animals to attract mates, ensuring successful reproduction.

Physiological Adaptations

These are internal body processes or functions that allow an organism to survive in its environment. They often involve biochemistry and metabolism.

- Venom Production: Snakes and spiders produce toxins to subdue prey or defend themselves.

- Antifreeze Proteins: Fish living in polar waters produce special proteins that prevent their blood from freezing.

- Water Conservation: The ability of a camel to store water and extract moisture from its food, or a desert plant’s specialized roots and waxy leaves to minimize water loss.

- Temperature Regulation: Sweating in humans or panting in dogs to cool down, or shivering to generate heat.

- Digestive Enzymes: Specialized enzymes that allow certain organisms to digest unique food sources, like bacteria in the gut of termites that break down cellulose.

The Engine of Adaptation: Natural Selection

While adaptations are traits, the driving force behind their prevalence and evolution is natural selection. This fundamental mechanism, first articulated by Charles Darwin, explains how populations change over time, becoming better suited to their environments. It is not a conscious choice by organisms, but rather a consequence of differential survival and reproduction.

The process of natural selection can be broken down into four key steps:

- Variation: Within any population of organisms, individuals exhibit natural differences in their traits. For example, some rabbits might have brown fur, while others have grey or white fur. This variation arises from random mutations in DNA.

- Inheritance: Many of these variations are heritable, meaning they can be passed down from parents to their offspring. A brown-furred rabbit is likely to have brown-furred kits.

- Selection: In any given environment, resources are limited, leading to a “struggle for existence.” Individuals with traits that make them better suited to their environment are more likely to survive, find food, avoid predators, and reproduce. For instance, brown rabbits might be better camouflaged in a forest than white rabbits, making them less likely to be caught by a fox.

- Time -> Adaptation: Over many generations, the advantageous traits become more common in the population because the individuals possessing them have greater reproductive success. The population as a whole gradually adapts to its environment, with the favored traits becoming widespread.

This continuous cycle of variation, inheritance, selection, and reproduction leads to the gradual refinement of species, allowing them to become incredibly well-suited to their specific ecological niches.

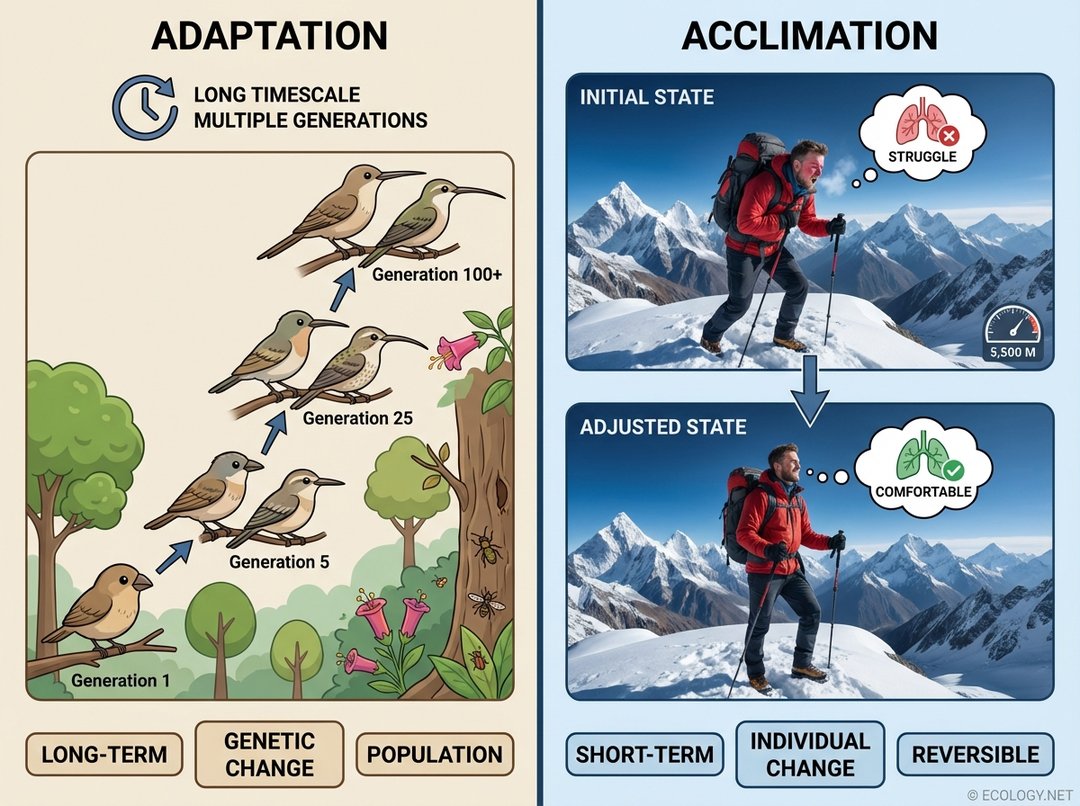

Adaptation vs. Acclimation: A Crucial Distinction

It is common to confuse adaptation with acclimation, but they represent fundamentally different biological processes. While both involve adjusting to environmental conditions, their mechanisms, timescales, and heritability differ significantly.

Adaptation is an evolutionary process that occurs over multiple generations, leading to a genetic change in a population. It is long-term and heritable.

Acclimation is a short-term, reversible physiological adjustment made by an individual organism in response to environmental changes. It is not genetic and cannot be passed to offspring.

Consider these examples:

- Adaptation Example: The thick fur coat of an arctic fox is an adaptation. Its ancestors with slightly thicker fur survived better in cold environments, reproduced more, and passed on their genes. This trait is now genetically encoded in the species.

- Acclimation Example: When a human travels from sea level to a high-altitude mountain, their body acclimates by producing more red blood cells over a few weeks to compensate for lower oxygen levels. This is a temporary, individual adjustment that is not passed on to their children. If they return to sea level, their red blood cell count will eventually return to normal.

Another way to think about it is that adaptation is a permanent, population-level change driven by evolution, while acclimation is a temporary, individual-level response to immediate environmental stress.

The Wonders of Adaptation: More Examples and Insights

The natural world is brimming with astonishing adaptations that highlight the power of natural selection.

- Deep-Sea Life: Organisms living in the abyssal plains have adapted to extreme pressure, perpetual darkness, and scarce food. Many have developed bioluminescence for communication or attracting prey, and some have slow metabolisms to conserve energy.

- Desert Plants: Cacti have evolved thick, waxy cuticles to reduce water loss, shallow but widespread root systems to quickly absorb surface water, and spines instead of leaves to minimize evaporation and deter herbivores.

- Predator-Prey Arms Race: The constant coevolution between predators and prey drives a fascinating cycle of adaptation. A gazelle’s speed is an adaptation to escape cheetahs, while the cheetah’s speed and agility are adaptations to catch gazelles.

- Symbiotic Relationships: The mutualistic relationship between clownfish and sea anemones is an adaptation where the clownfish develops immunity to the anemone’s stings, gaining protection, while the anemone benefits from the clownfish cleaning it and luring other fish.

Adaptation in a Changing World

While adaptation is a powerful force, its pace is often slow, unfolding over thousands or even millions of years. In our rapidly changing world, this presents significant challenges. Climate change, habitat destruction, and pollution are altering environments at an unprecedented rate, often too quickly for many species to adapt through natural selection.

Organisms with short generation times and high reproductive rates, like bacteria or insects, can sometimes adapt more quickly to new challenges, such as antibiotic resistance or pesticide resistance. However, long-lived species with slow reproductive cycles face a much greater hurdle. Understanding the mechanisms and limitations of adaptation is therefore crucial for conservation efforts and for predicting how ecosystems will respond to future environmental shifts.

Conclusion

Adaptation is not merely a biological concept; it is the very essence of life’s enduring journey. It is the story of how a tiny seed can grow into a towering tree in a specific climate, how a fish can navigate the crushing depths of the ocean, and how a bird can soar across continents. By understanding structural, behavioral, and physiological adaptations, and the engine of natural selection that drives them, we gain profound insights into the intricate beauty and resilience of the natural world. Every creature, in its unique form and function, is a living testament to the power of adaptation, a continuous dance between life and its ever-changing environment.