Imagine a world so vast, so ancient, and so profoundly influential that it shapes the very air we breathe and the climate we experience. This is the realm of marine ecosystems, the intricate web of life found within our planet’s oceans, seas, and coastal waters. Far from being uniform, these underwater worlds are incredibly diverse, ranging from sunlit coral gardens to the crushing darkness of the deep sea, each teeming with unique life forms adapted to their specific environments.

Marine ecosystems are essentially life support systems found in saltwater. They encompass all living organisms, from microscopic plankton to colossal whales, interacting with their physical surroundings, including water, sunlight, temperature, salinity, and pressure. These interactions create complex food webs and cycles that are vital not only for marine life but for the entire planet.

The Diverse Tapestry of Marine Ecosystems

The ocean is not a single, monolithic environment. Instead, it is a mosaic of distinct ecosystems, each with its own characteristics and inhabitants. Understanding these different types helps us appreciate the incredible adaptability of life.

Coastal Ecosystems: Where Land Meets Sea

Coastal areas are dynamic zones where freshwater often mixes with saltwater, and land influences marine conditions. These regions are among the most productive on Earth, supporting an astonishing array of life.

-

Coral Reefs: The Rainforests of the Sea

These vibrant underwater cities are built by tiny polyps over thousands of years. Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots, providing shelter and food for a quarter of all marine species, despite covering less than one percent of the ocean floor. Their intricate structures support complex food webs, from grazing parrotfish to predatory sharks. However, these delicate ecosystems are highly sensitive to changes in ocean temperature and acidity, making them particularly vulnerable to climate change.

This image beautifully illustrates the rich biodiversity of coral reefs and the intricate relationships among producers, consumers, and decomposers, highlighting their sensitivity to temperature and acidity changes discussed in the article.

-

Estuaries and Mangrove Forests: Nurseries of the Ocean

Estuaries are semi enclosed coastal bodies of water where freshwater rivers or streams meet and mix with the ocean. This creates a unique brackish environment, fluctuating in salinity with the tides. Estuaries are incredibly productive, acting as vital nurseries for many fish, shellfish, and bird species. Mangrove forests, found in tropical and subtropical coastal areas, are a type of estuarine ecosystem characterized by salt tolerant trees with distinctive root systems. These roots provide critical habitat, stabilize coastlines, and filter pollutants from the water.

This image depicts estuarine ecosystems, their productivity, and the mix of fresh and saltwater habitats that support diverse life, as highlighted in the article.

-

Kelp Forests: Underwater Giants

In cooler waters, vast underwater forests of giant kelp sway with the currents. These towering algae provide shelter, food, and hunting grounds for a multitude of marine organisms, including sea otters, fish, and invertebrates. Kelp forests are highly productive and play a crucial role in coastal food webs.

Open Ocean Ecosystems: The Vast Blue

Beyond the coasts lies the expansive open ocean, often called the pelagic zone. This vast area is characterized by its depth, distance from land, and varying light levels.

-

Sunlit Zone (Epipelagic): The Ocean’s Surface

This uppermost layer, extending down to about 200 meters, receives enough sunlight for photosynthesis. It is home to phytoplankton, microscopic plants that form the base of most marine food webs, producing much of the oxygen we breathe. Zooplankton graze on phytoplankton, and in turn, are consumed by small fish, leading up to larger predators like tuna, dolphins, and whales.

-

Twilight Zone (Mesopelagic): A World of Dim Light

Below the sunlit zone, from 200 to 1,000 meters, light levels are too low for photosynthesis. Creatures here are often adapted with large eyes to capture faint light or possess bioluminescence, the ability to produce their own light. Many species migrate vertically, feeding in the sunlit zone at night and retreating to the depths during the day to avoid predators.

-

Midnight Zone (Bathypelagic) and Abyssal Zone: Eternal Darkness

From 1,000 meters downwards, the ocean is in perpetual darkness. Life here relies on food falling from above, known as marine snow, or on specialized adaptations. The abyssal zone, covering the deep ocean floor, is characterized by immense pressure, cold temperatures, and sparse food resources. Yet, even here, life persists, often with slow metabolisms and unique feeding strategies.

Deep Sea Ecosystems: Worlds Without Sun

The deep sea represents one of Earth’s most extreme environments, yet it harbors astonishing biodiversity and unique ecological processes.

-

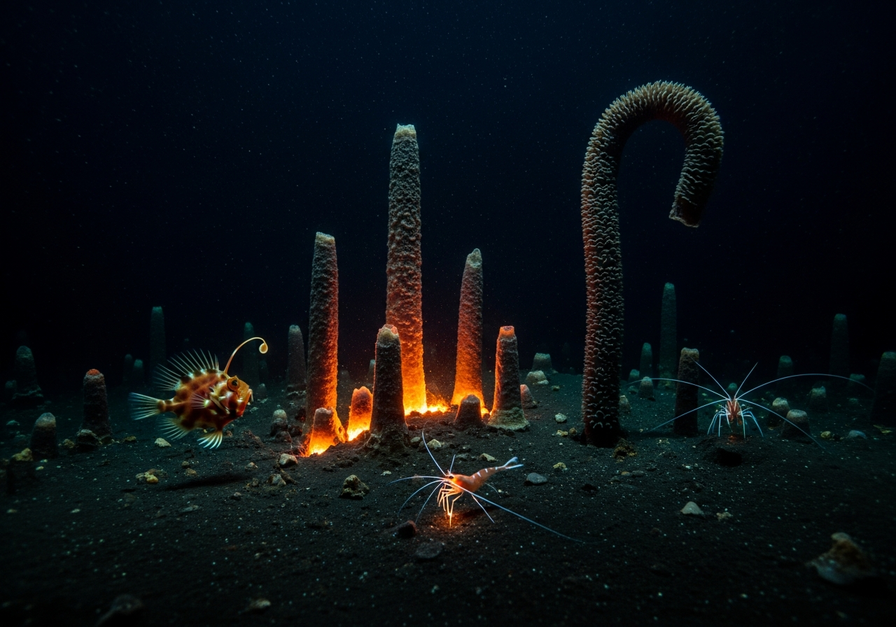

Hydrothermal Vents: Oases of Chemosynthesis

Perhaps the most extraordinary deep sea ecosystems are found around hydrothermal vents. These fissures in the seafloor release superheated, mineral rich water. Instead of relying on sunlight for energy, these ecosystems are powered by chemosynthesis, where specialized bacteria convert chemicals from the vents into organic matter. This supports a thriving community of unique organisms, including giant tube worms, specialized shrimp, and crabs, all living in conditions that would be toxic to most other life forms.

This image illustrates the deep sea ecosystem’s unique food sources, extreme abiotic conditions, and the role of hydrothermal vents in sustaining life without sunlight, reinforcing the article’s discussion of deep sea ecosystems.

-

Cold Seeps: Another Form of Chemosynthesis

Similar to hydrothermal vents, cold seeps also support chemosynthetic communities. However, instead of hot water, they release methane and hydrogen sulfide at ambient deep sea temperatures. These seeps host unique mussels, clams, and tube worms, demonstrating another pathway for life to flourish in the absence of sunlight.

The Interconnected Web of Life

Regardless of their specific location, all marine ecosystems are defined by the interplay of abiotic (non living) and biotic (living) factors.

Abiotic Factors: The Ocean’s Architects

- Temperature: Influences metabolic rates and species distribution.

- Salinity: The salt content of water, crucial for osmotic balance in marine organisms.

- Light: Essential for photosynthesis in the upper layers, dictating where primary production can occur.

- Pressure: Increases dramatically with depth, requiring specialized adaptations for deep sea life.

- Nutrients: Availability of nitrates, phosphates, and silicates drives primary productivity.

Biotic Factors: The Ocean’s Inhabitants

- Producers: Primarily phytoplankton and algae, which convert sunlight or chemicals into energy.

-

Consumers:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Zooplankton, grazing fish, and sea turtles that feed on producers.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores): Fish, seals, and seabirds that eat primary consumers.

- Tertiary Consumers (Top Predators): Sharks, killer whales, and large tuna that feed on other carnivores.

- Decomposers: Bacteria and fungi that break down dead organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem.

These components are intricately linked through complex food webs. For example, a tiny copepod grazing on phytoplankton might be eaten by a small fish, which in turn becomes prey for a larger fish, eventually feeding a marine mammal or seabird. Any disruption in one part of this web can have cascading effects throughout the entire ecosystem.

Threats and the Imperative for Conservation

Marine ecosystems, despite their vastness, are facing unprecedented threats from human activities. Understanding these challenges is the first step towards protecting these vital environments.

- Climate Change: Rising ocean temperatures lead to coral bleaching and alter species distributions. Ocean acidification, caused by increased absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide, makes it harder for shell forming organisms to build and maintain their shells, impacting everything from plankton to corals.

- Pollution: Plastic pollution chokes marine life and contaminates food chains. Chemical runoff from land, including pesticides and fertilizers, creates dead zones by fueling algal blooms that deplete oxygen. Oil spills devastate coastal habitats and marine animals.

- Overfishing: Depletion of fish stocks disrupts marine food webs and can lead to the collapse of entire populations. Destructive fishing practices, such as bottom trawling, destroy critical habitats like coral reefs and seafloor communities.

- Habitat Destruction: Coastal development, dredging, and unsustainable aquaculture practices destroy vital habitats like mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass beds, which serve as nurseries and protective barriers.

Protecting marine ecosystems requires a global effort. This includes reducing carbon emissions, managing fisheries sustainably, curbing pollution, and establishing marine protected areas. Every action, from reducing plastic use to supporting sustainable seafood choices, contributes to the health of our oceans.

Conclusion: Our Ocean, Our Future

Marine ecosystems are not just distant, exotic places; they are fundamental to the health of our planet and our own well being. They regulate climate, produce oxygen, provide food, and offer immense recreational and aesthetic value. From the dazzling complexity of a coral reef to the mysterious depths of a hydrothermal vent, these underwater worlds are testaments to life’s incredible resilience and diversity.

By deepening our understanding and fostering a sense of stewardship, we can work towards ensuring that these magnificent marine ecosystems continue to thrive, supporting life both within their waters and across the globe, for generations to come. The future of our blue planet depends on it.