Life on Earth is a tapestry woven from countless interactions. From fierce predator-prey dynamics to cooperative partnerships, every species is connected in a complex web. Among these fascinating relationships, one often flies under the radar, a subtle yet pervasive dance where one party benefits while the other remains seemingly untouched. This intriguing ecological arrangement is known as commensalism.

For anyone curious about the hidden workings of nature, understanding commensalism unlocks a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity and adaptability of life. It is a concept that challenges our assumptions about how species coexist, revealing a world where advantage can be gained without causing harm or offering direct reward.

Unpacking Commensalism: The Basics

At its core, commensalism describes a relationship between two different species where one organism benefits, and the other is neither helped nor harmed. The term itself originates from the Latin “com mensa,” meaning “at the same table,” aptly describing how one species might partake in the resources or opportunities created by another without altering the host’s experience.

This definition sets commensalism apart from other well-known symbiotic relationships:

- Mutualism: Both species benefit. Think of bees pollinating flowers.

- Parasitism: One species benefits at the expense of the other. A tick feeding on a dog is a classic example.

- Competition: Both species are harmed as they vie for the same limited resources.

- Amensalism: One species is harmed, while the other is unaffected. For instance, a large tree shading out smaller plants below it.

The key differentiator for commensalism is that crucial “unaffected” status of the second party. This neutrality is what makes it so intriguing and, at times, challenging to definitively prove in the wild.

Classic Examples of Commensalism in Action

The natural world is brimming with examples of commensalism, showcasing diverse strategies for one organism to gain an advantage without impacting its unwitting partner.

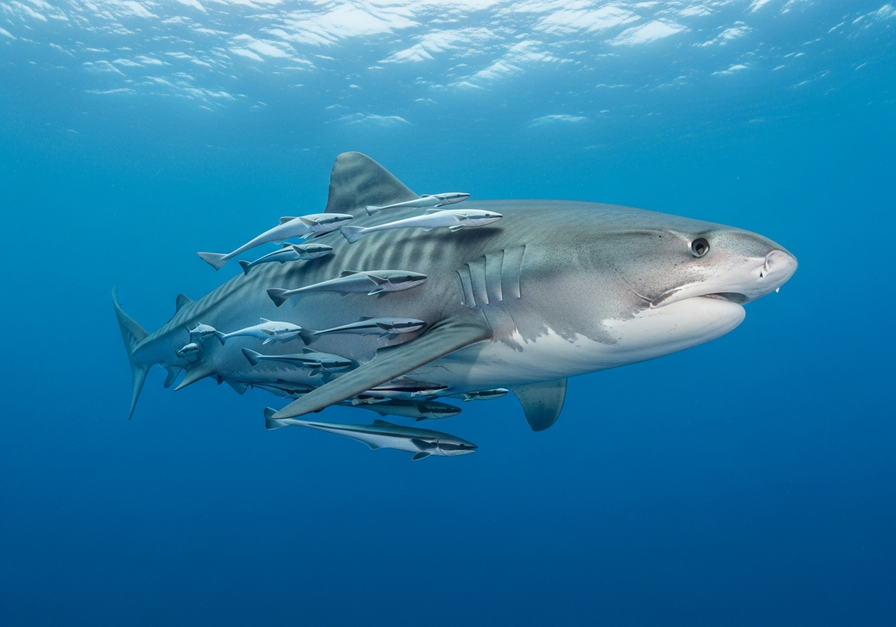

- Remoras and Sharks: Perhaps one of the most iconic examples. Remora fish possess a modified dorsal fin that acts as a powerful suction cup, allowing them to attach to larger marine animals like sharks, whales, or manta rays. The remoras benefit by gaining free transportation, protection from predators, and scraps of food left over from the shark’s meals. The shark, being large and powerful, is generally considered unaffected by the presence of a few remoras.

- Cattle Egrets and Livestock: These elegant white birds are frequently observed in fields alongside grazing cattle, horses, or other large mammals. As the livestock move through the grass, they stir up insects and other small invertebrates. The egrets, with their keen eyesight, then swoop in to catch these disturbed prey items. The egrets get an easy meal, and the livestock are typically unbothered by their avian companions.

- Barnacles on Whales: Barnacles are sessile crustaceans that attach themselves to hard surfaces. Many species of barnacles attach to the skin of whales. They benefit from constant access to nutrient-rich water currents as the whale swims, bringing them food particles. They also gain a mobile habitat and protection from predators. The whale, with its massive size and thick skin, is generally not harmed or inconvenienced by the barnacles.

- Tree Frogs and Plants: Many species of tree frogs use plants, particularly large-leafed tropical plants, for shelter and camouflage. They perch on leaves or hide in crevices, gaining protection from predators and the elements. The plant itself is not consumed or damaged by the frog’s presence.

- Scavengers Following Predators: Certain smaller scavengers, like jackals or some bird species, will follow large predators such as lions or wolves. They wait for the predator to finish its meal and then move in to consume the leftovers. The scavengers benefit from an easy food source, while the predator, having had its fill, is usually indifferent to the scavengers cleaning up.

The Many Faces of Commensalism: Types and Mechanisms

Commensalism is not a monolithic concept. Ecologists recognize several distinct ways in which one species can benefit without affecting another. These categories help us understand the specific mechanisms at play.

- Phoresy: This type of commensalism involves one organism using another for transportation. The “passenger” gains mobility, while the “host” is generally unaware or unaffected by the hitchhiker.

- Example: Mites attaching to insects like dung beetles for dispersal to new food sources. The mites get a ride, and the beetle’s flight or movement is not significantly impeded.

- Example: Pseudo-scorpions clinging to the legs of larger beetles or mammals to travel further distances.

- Inquilinism: Here, one organism lives in or on another organism, often using it as a permanent or semi-permanent habitat, without being a parasite.

- Example: Orchids and bromeliads growing as epiphytes on tree branches. They use the tree for support and access to sunlight, but they do not draw nutrients from the tree itself.

- Example: Birds nesting in holes in trees. The tree provides shelter, and the birds do not harm the tree.

- Example: Pearlfish living inside the cloaca of sea cucumbers. The fish gains shelter and protection, and the sea cucumber is typically unharmed.

- Metabiosis: This is an indirect form of commensalism where one organism creates or modifies a habitat that is then used by another species. The first organism is not directly involved in the second’s life but provides the necessary conditions.

- Example: Hermit crabs using discarded snail shells for protection. The snail’s death creates the shell, which the hermit crab then utilizes.

- Example: Maggots feeding on a dead animal carcass. The animal’s death provides a food source and habitat for the maggots.

- Nutritional Commensalism: This involves one organism benefiting from the food scraps, waste products, or undigested materials of another.

- Example: The aforementioned remoras and sharks, where remoras consume food scraps.

- Example: Scavenger birds following army ants to catch insects fleeing the ant column.

The Elusive “Unaffected”: Challenges in Identification

While the definition of commensalism seems straightforward, proving that the host is truly “unaffected” can be one of the greatest challenges for ecologists. Nature is rarely simple, and subtle costs or benefits can easily be overlooked.

The line between commensalism and other interactions is often blurred. What appears to be a neutral interaction today might, under different environmental conditions or over longer timescales, reveal a slight cost or benefit to the host.

- Subtle Costs: A small energetic cost for a shark carrying remoras, a minor increase in drag for a whale with barnacles, or a tiny amount of shade cast by an epiphyte on a tree branch could, theoretically, have an impact. These impacts might be negligible in most circumstances but could become significant under stress.

- Subtle Benefits: Conversely, what if the remoras clean parasites off the shark’s skin, or the barnacles provide a protective layer against some external threat? Such benefits would shift the relationship towards mutualism.

- Dynamic Nature: Ecological relationships are not static. A commensal relationship might become parasitic if the population of the beneficiary explodes, or it could evolve into mutualism over evolutionary time.

Because of these complexities, many interactions initially classified as commensal are subject to ongoing scientific scrutiny. Rigorous studies are required to measure even minute impacts on the host’s fitness, survival, or reproductive success.

Ecological Significance and Broader Implications

Despite the challenges in its precise definition, commensalism plays a vital role in shaping ecological communities and contributing to biodiversity.

- Facilitating Coexistence: Commensal relationships allow species to share habitats and resources without direct competition or conflict. This can increase the overall number of species that can thrive in a given area.

- Niche Expansion: For the benefiting species, commensalism can open up new ecological niches that would otherwise be inaccessible. For example, epiphytes can access sunlight high in the canopy without needing to develop a massive root system in the ground.

- Resource Utilization: Commensalism ensures that resources, such as discarded food or available shelter, are not wasted. It represents an efficient way for life to capitalize on every opportunity.

- Community Structure: These interactions contribute to the intricate web of life, adding layers of complexity and interdependence that define healthy ecosystems. They can influence food webs, habitat distribution, and even the spread of species.

Advanced Perspectives: From Obligate to Opportunistic

Just as with other symbiotic relationships, commensalism can exist along a spectrum of dependency.

- Facultative Commensalism: In this common scenario, the benefiting species can survive and reproduce without the host, but it gains an advantage by associating with it. Most of the examples discussed above, like cattle egrets or remoras, fall into this category. They can find food or transport independently, but it is easier with a host.

- Obligate Commensalism: This is a rarer and more extreme form where the benefiting species absolutely requires the host for survival, even though the host remains unaffected. Proving true obligate commensalism is exceptionally difficult because if the host is truly essential, any subtle harm to the host could eventually impact the commensal, blurring the lines towards parasitism or mutualism. However, some deep‑sea vent organisms that rely on specific chemical byproducts of other organisms might approach this.

The Microbial World: A Commensal Hotbed

When we think of commensalism, our minds often jump to large animals, but the microscopic world is arguably where these interactions are most prevalent and profound.

- Human Microbiome: Our bodies are teeming with trillions of microorganisms. Many bacteria living on our skin or in our gut are considered commensals. They benefit from a stable environment and abundant nutrients. While some gut bacteria are mutualistic (aiding digestion, producing vitamins), many others simply reside without causing harm or offering a direct, measurable benefit to us.

- Soil Microbes: Vast communities of bacteria and fungi in the soil live off the waste products or dead organic matter produced by plants and other soil organisms. Many of these are commensal, benefiting from the environment created by other life forms without directly impacting them.

Observing the Unseen: The Wonder of Commensalism

Commensalism reminds us that not all interactions in nature are about conflict or explicit cooperation. Sometimes, life simply finds a way to thrive by subtly leveraging the existence of another. It is a testament to the incredible adaptability of species and the intricate ways in which ecosystems are structured.

The next time a nature documentary highlights a shark and its remoras, or a bird foraging near grazing animals, take a moment to appreciate the silent, often overlooked, dance of commensalism. It is a relationship that challenges our perceptions and invites us to look closer, to question the obvious, and to marvel at the quiet ingenuity of life on Earth.