Unraveling Life’s Blueprint: An Introduction to Life History Strategies

Every living organism, from the tiniest bacterium to the colossal blue whale, faces a fundamental challenge: how to best allocate its limited time and energy to survive and reproduce. This isn’t a conscious decision, but rather a grand evolutionary gamble, refined over millennia through natural selection. The unique set of adaptations an organism evolves to navigate this challenge is known as its life history strategy.

Life history strategies encompass a wide array of traits, including an organism’s age at first reproduction, the number and size of its offspring, its reproductive frequency, and its lifespan. Understanding these strategies is crucial for ecologists, conservationists, and anyone curious about the incredible diversity and ingenuity of life on Earth. It helps us comprehend why some species live fast and die young, while others take their time, investing heavily in a few precious offspring.

The Fundamental Trade-offs: Life’s Balancing Act

At the heart of every life history strategy lies a series of unavoidable trade-offs. An organism has a finite amount of energy and resources available throughout its life. This energy must be distributed among competing demands: growth, maintenance (survival), and reproduction. Investing more in one area often means investing less in another.

Consider a young animal. Should it grow quickly to reach a size where it’s less vulnerable to predators, or should it mature early and start reproducing? If it reproduces, should it produce many small offspring with little individual investment, or a few large, well-provisioned offspring? These are the dilemmas that natural selection “solves” over evolutionary time, leading to the diverse strategies we observe.

This image visually represents the fundamental concept of trade-offs in life history strategies, showing how organisms must allocate limited energy among competing demands like growth, survival, and reproduction.

- Growth vs. Reproduction: Organisms that grow larger often delay reproduction, but their larger size might lead to more successful reproduction later. Conversely, early reproduction can limit growth.

- Survival vs. Reproduction: Investing heavily in reproduction can deplete an organism’s energy reserves, making it more vulnerable to disease, predation, or starvation, thereby reducing its chances of future survival.

- Number of Offspring vs. Offspring Quality: Producing many offspring often means each individual offspring receives less parental investment, making them smaller or less prepared for survival. Producing fewer offspring allows for greater investment in each, potentially increasing their individual survival chances.

The Great Divide: r-Selection and K-Selection

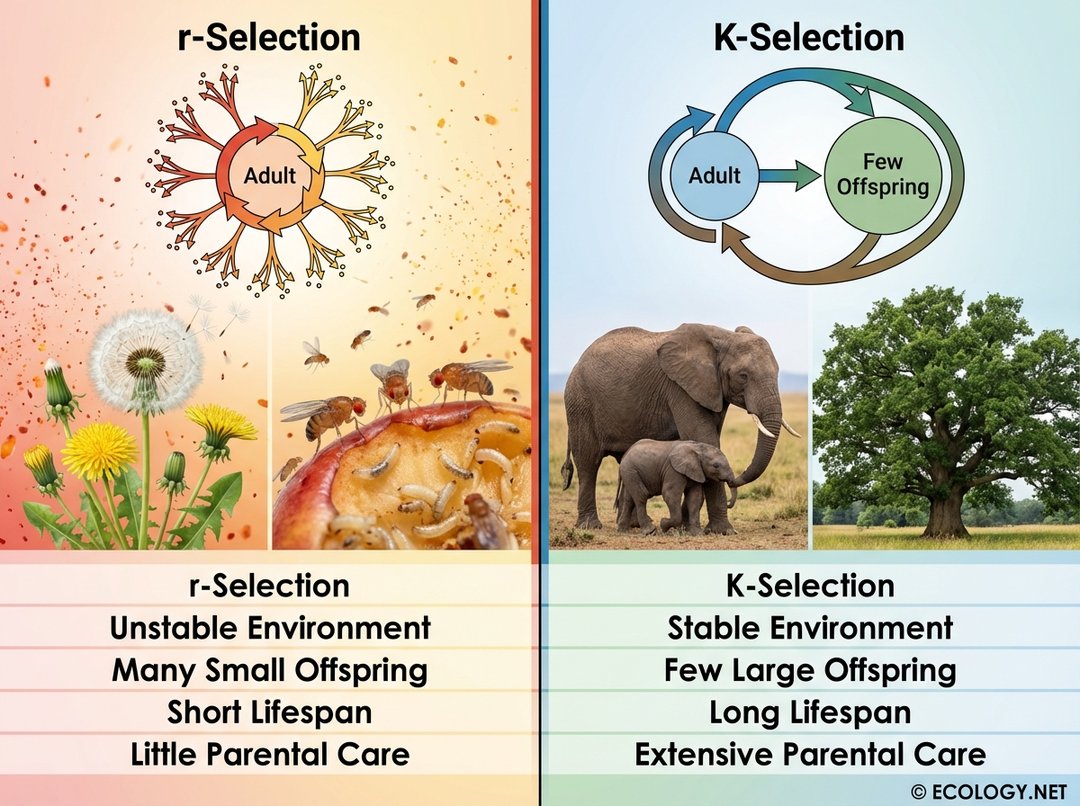

One of the most widely recognized frameworks for categorizing life history strategies is the distinction between r-selection and K-selection. These terms describe two ends of a continuum, representing adaptations to different environmental conditions.

This image provides a clear visual distinction between the two major life history strategies, r-selection and K-selection, by highlighting their key characteristics and providing concrete examples from the article.

r-Selected Species: The Opportunists

Species exhibiting r-selected strategies thrive in unpredictable, unstable environments where resources are often abundant but competition is low. Their strategy is to reproduce quickly and in vast numbers, capitalizing on fleeting opportunities.

- Rapid Growth and Early Reproduction: They mature quickly and begin reproducing at a young age.

- Many Small Offspring: They produce a large number of offspring, each typically small and requiring minimal parental care. The hope is that at least a few will survive.

- Short Lifespan: Individual organisms often have short lifespans, as their environment is not conducive to long-term survival.

- High Mortality Rates: Offspring mortality is very high, but the sheer numbers produced ensure some reach reproductive age.

- Examples: Dandelions, fruit flies, bacteria, many insects, annual plants, and most weeds. These organisms are excellent colonizers of new habitats.

K-Selected Species: The Strategists

K-selected species, in contrast, are adapted to stable, predictable environments where resources are limited and competition is intense. Their strategy emphasizes quality over quantity, with significant investment in each offspring.

- Slow Growth and Delayed Reproduction: They grow slowly, mature later, and typically have a longer juvenile period.

- Few Large Offspring: They produce a small number of offspring, each relatively large and receiving extensive parental care and investment.

- Long Lifespan: Individuals tend to have long lifespans, increasing their chances of multiple reproductive events.

- Low Mortality Rates: Offspring mortality is relatively low due to parental care and investment, increasing the survival rate of each individual.

- Examples: Elephants, oak trees, whales, humans, large mammals, and many birds of prey. These species are strong competitors in their established niches.

It is important to remember that r- and K-selection represent a spectrum, not strict categories. Many species exhibit traits that fall somewhere in between these two extremes, adapting to the specific pressures of their unique ecological niche.

Reproductive Timing: Semelparity vs. Iteroparity

Beyond the r/K framework, another critical aspect of life history strategies is the timing and frequency of reproduction. This leads to two distinct patterns: semelparity and iteroparity.

This image illustrates a crucial distinction in reproductive timing, semelparity (single reproduction) versus iteroparity (multiple reproductions), offering a deeper understanding of life history variations beyond the r/K framework.

Semelparity: The “Big Bang” Reproducers

Semelparous organisms reproduce only once in their lifetime, often in a single, massive reproductive effort, and then typically die shortly thereafter. This strategy is sometimes referred to as “big bang” reproduction.

- Single, Massive Reproductive Event: All available energy is channeled into one grand reproductive effort.

- High Investment: The single reproductive event often involves producing a very large number of offspring.

- Post-Reproductive Death: The organism’s body is so depleted by the reproductive effort that it cannot survive afterwards.

- Evolutionary Drivers: This strategy is favored in environments where the chances of surviving to reproduce again are very low, or where there is a strong advantage to synchronizing reproduction with a rare, favorable environmental window.

- Examples: Pacific salmon, which swim upstream to spawn and then die; annual plants like corn or wheat; many insects such as mayflies; and the agave plant, which flowers once after decades of growth and then perishes.

Iteroparity: The Repeated Reproducers

Iteroparous organisms, by contrast, reproduce multiple times throughout their lifespan. They spread their reproductive efforts over several seasons or years.

- Multiple Reproductive Events: Energy is allocated to reproduction in smaller, repeated installments.

- Lower Investment Per Event: Each reproductive event typically involves fewer offspring compared to a semelparous species’ single event.

- Survival Between Events: Organisms survive and recover between reproductive bouts, allowing for future opportunities.

- Evolutionary Drivers: This strategy is favored in stable environments where the chances of surviving to reproduce again are high, and where offspring survival might be unpredictable from year to year. Spreading out reproduction reduces the risk of total reproductive failure.

- Examples: Most mammals, including humans; most birds; perennial plants like oak trees; and many fish species like cod.

Factors Shaping Life History Strategies

The specific life history strategy adopted by a species is a complex outcome of various environmental and ecological pressures:

- Environmental Stability: Predictable, stable environments often favor K-selected, iteroparous strategies, while unpredictable, fluctuating environments favor r-selected, semelparous strategies.

- Predation Pressure: High predation rates can favor early reproduction and many offspring (r-selection) to ensure some genetic legacy before being consumed. Low predation might allow for greater investment in fewer, well-protected offspring (K-selection).

- Resource Availability: Abundant resources can support large numbers of offspring, while scarce resources necessitate careful allocation and often fewer, higher-quality offspring.

- Mortality Rates: If adult mortality is high, selection favors early and frequent reproduction. If juvenile mortality is high, selection favors parental investment to improve offspring survival.

- Competition: Intense competition for resources can favor traits that enhance competitive ability, often associated with K-selection.

The Dynamic Nature of Life Histories

It is crucial to understand that life history strategies are not static. They can exhibit plasticity, meaning an individual organism might adjust its reproductive timing or effort in response to changing environmental conditions. For instance, a plant might produce more seeds in a year with abundant rainfall. Furthermore, within a species, different populations living in varying environments might evolve slightly different life history traits.

The concept of life history strategies also highlights the interconnectedness of an organism’s traits. A long lifespan is often linked to delayed reproduction and fewer offspring, while a short lifespan is typically associated with early and prolific reproduction. These traits co-evolve as a cohesive package, optimized for survival and reproduction in a particular ecological context.

Why Life History Strategies Matter: Practical Insights

Understanding life history strategies is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for various real-world applications:

- Conservation Biology: Knowing a species’ life history helps conservationists design effective strategies. K-selected species, with their slow reproduction and long generation times, are often more vulnerable to extinction from habitat loss or overhunting, as their populations recover slowly. r-selected species, while resilient to local disturbances, can still be threatened by widespread habitat destruction.

- Pest Control: Many agricultural pests are r-selected species, characterized by rapid reproduction and high population growth rates. Effective pest control strategies must account for this, often targeting multiple life stages or preventing reproduction.

- Fisheries Management: Sustainable fishing practices require knowledge of fish life histories, including their age at maturity, reproductive output, and lifespan, to set appropriate catch limits and protect breeding populations.

- Human Health and Demography: Human life history, characterized by a long lifespan, delayed reproduction, and extensive parental care, has shaped our societies and cultures. Understanding these traits helps demographers predict population trends and public health needs.

- Evolutionary Biology: Life history theory provides a powerful framework for understanding the evolutionary forces that shape the incredible diversity of life on Earth, explaining why organisms look and behave the way they do.

Conclusion: The Tapestry of Life

Life history strategies represent the intricate blueprints that organisms follow to navigate the fundamental challenges of existence. From the frantic, prolific reproduction of an r-selected dandelion to the slow, deliberate investment of a K-selected elephant, each strategy is a testament to the power of natural selection to sculpt life in response to its environment. By appreciating these diverse approaches to survival and reproduction, we gain a deeper understanding of the ecological world around us and the remarkable adaptability of all living things.