Imagine a bustling city where every building, every street, and every citizen knows exactly what to do, when to do it, and how to react to changing conditions. Now, imagine this city is a plant. How does it manage such intricate coordination without a brain or a nervous system? The answer lies in a remarkable group of chemical messengers: plant hormones.

Often overlooked in favor of their animal counterparts, plant hormones, also known as phytohormones, are the silent architects of the plant world. They are powerful organic compounds produced in minute quantities that regulate virtually every aspect of plant life, from the moment a seed germinates to the eventual senescence of leaves and ripening of fruit. Understanding these molecular maestros unlocks a deeper appreciation for the incredible adaptability and resilience of flora around us.

The Major Players: A Symphony of Growth and Development

Just as a symphony orchestra relies on different sections to create a harmonious piece, plants depend on a diverse cast of hormones, each with its unique role. While many compounds influence plant growth, five major classes are universally recognized for their profound impact.

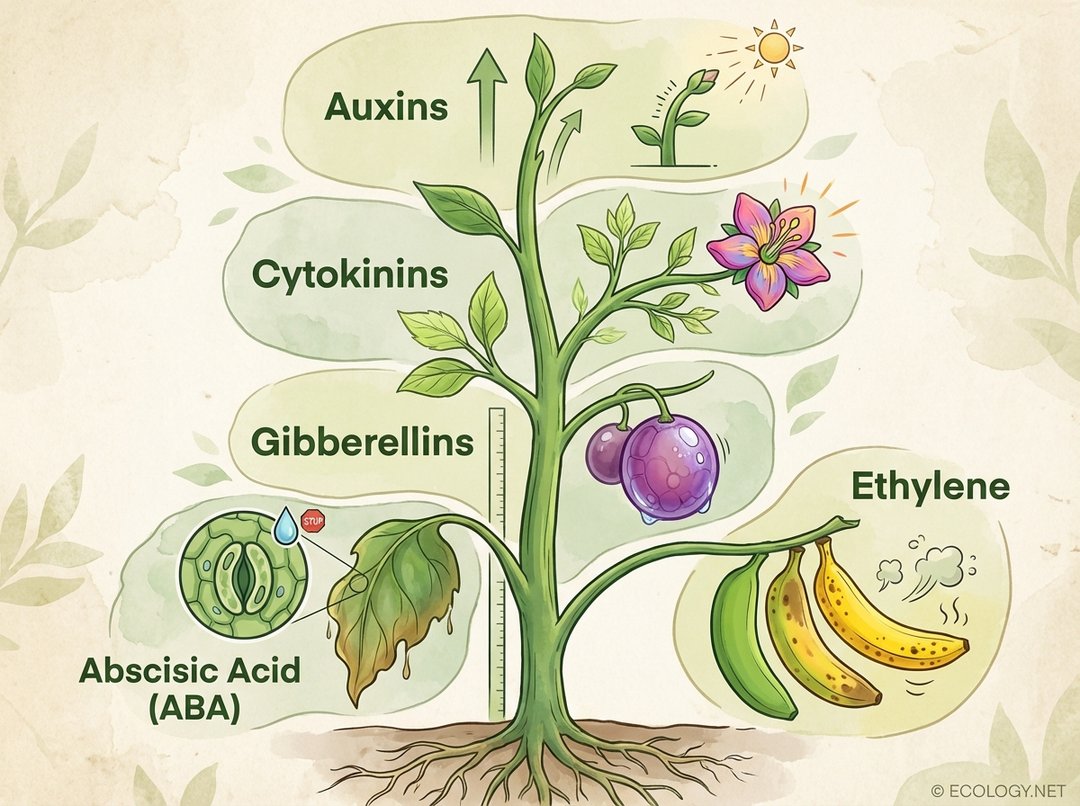

This image provides a quick visual summary of the five main plant hormones discussed in the article and their diverse roles, making the ‘Major Players’ section immediately understandable and engaging.

1. Auxins: The Architects of Direction and Dominance

Auxins were the first plant hormones discovered, and their name, derived from the Greek word “auxein” meaning “to grow,” perfectly encapsulates their primary function. Produced primarily in the apical meristems (the tips of shoots and roots) and young leaves, auxins are crucial for:

- Cell Elongation: They promote the stretching of cells, particularly in stems, leading to upward growth. This is why plants bend towards light (phototropism) and roots grow downwards (gravitropism), as auxins redistribute to shaded or lower sides, respectively, stimulating differential growth.

- Apical Dominance: Auxins produced by the apical bud inhibit the growth of lateral (side) buds. This ensures the plant grows taller rather than bushier, a strategy to reach sunlight. Pruning the apical bud removes this auxin source, allowing side branches to flourish.

- Root Initiation: In contrast to their shoot-promoting role, auxins are vital for initiating root formation, a principle widely used in horticulture for propagating plants from cuttings.

- Fruit Development: They play a role in the development of fruits, often preventing their premature abscission (shedding).

2. Cytokinins: The Stimulators of Cell Division

Cytokinins, primarily synthesized in the roots and transported upwards, are the hormones of proliferation. Their name reflects their key role in cytokinesis, the process of cell division. Their influence is widespread:

- Cell Division and Differentiation: They work in concert with auxins to regulate cell division and determine whether a mass of undifferentiated cells (callus) will develop into roots or shoots.

- Lateral Bud Growth: Cytokinins counteract auxin’s apical dominance, promoting the growth of lateral buds and contributing to a bushier plant habit.

- Delaying Senescence: They can delay the aging (senescence) of leaves and other plant parts, keeping them green and vibrant for longer.

3. Gibberellins: The Boosters of Growth and Germination

Gibberellins are a large family of chemically related compounds, best known for their dramatic effects on stem elongation and seed germination. They are found throughout the plant, with high concentrations in young leaves, roots, and developing seeds.

- Stem Elongation: Gibberellins cause significant increases in internode length, leading to taller plants. This effect is particularly noticeable in dwarf varieties, which often lack the ability to synthesize sufficient gibberellins.

- Seed Germination: They break seed dormancy, signaling to the embryo that conditions are right for growth. They stimulate the synthesis of enzymes that mobilize stored food reserves in the seed.

- Fruit Enlargement: Gibberellins are used commercially to increase the size of fruits like grapes, making them more appealing to consumers.

- Flowering: In some plants, gibberellins can induce flowering, especially in those requiring a cold period (vernalization).

4. Abscisic Acid (ABA): The Stress Manager and Dormancy Inducer

Often dubbed the “stress hormone,” Abscisic Acid (ABA) plays a critical role in helping plants cope with adverse environmental conditions and in regulating dormancy. It is produced in various plant parts, particularly in leaves, stems, and roots.

- Stomata Closure: Under drought conditions, ABA signals guard cells to close the stomata (pores on leaves), reducing water loss through transpiration. This is a crucial survival mechanism.

- Seed Dormancy: ABA maintains seed dormancy, preventing premature germination until favorable conditions arise. It acts antagonistically to gibberellins in this regard.

- Bud Dormancy: It promotes dormancy in buds, preparing plants for winter or other unfavorable periods.

- Leaf Abscission: While its name suggests a primary role in abscission (shedding of leaves), its direct involvement is less pronounced than once thought, though it does play a part in the overall process.

5. Ethylene: The Ripener and Senescence Accelerator

Unlike other plant hormones, ethylene is a simple gaseous hydrocarbon. Its unique gaseous nature allows it to diffuse rapidly through plant tissues and even into the surrounding air, influencing neighboring plants. It is produced by most plant tissues, especially during ripening, senescence, and in response to stress or injury.

- Fruit Ripening: Ethylene is the primary hormone responsible for fruit ripening, triggering changes in color, texture, and flavor. This is why one rotten apple can spoil the whole barrel, as the ethylene it releases accelerates ripening in others.

- Senescence and Abscission: It promotes the aging of flowers and leaves, and the shedding of leaves, flowers, and fruits.

- Triple Response: In seedlings, ethylene causes a characteristic “triple response” to mechanical stress: inhibition of stem elongation, thickening of the stem, and horizontal growth, helping the seedling navigate obstacles in the soil.

The Delicate Balance: Hormonal Ratios and Interactions

The true magic of plant hormones lies not just in their individual actions, but in their intricate interplay. They rarely act in isolation; instead, their effects are often determined by their relative concentrations, the sensitivity of target tissues, and their interactions with other hormones. This dynamic balance is what allows a plant to respond precisely to its internal state and external environment.

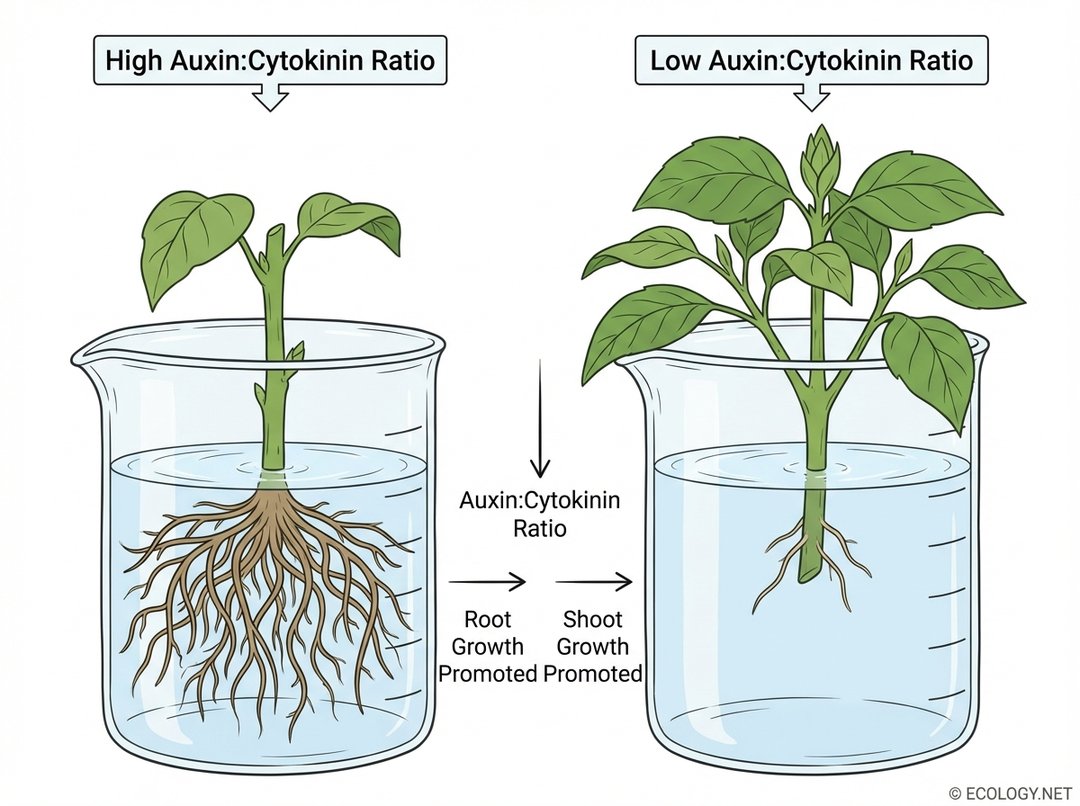

One of the most classic examples of this hormonal synergy is the auxin-cytokinin ratio, which dictates the developmental fate of plant cells.

This image visually explains the concept of hormonal balance, specifically the auxin-cytokinin ratio, which is crucial for understanding plant propagation and how different hormone concentrations dictate root versus shoot development.

- High Auxin:Cytokinin Ratio: Favors root development. This is why rooting hormones, which are synthetic auxins, are so effective in stimulating root growth on cuttings.

- Low Auxin:Cytokinin Ratio: Promotes shoot development. In tissue culture, adjusting this ratio allows scientists to regenerate entire plants from a few cells.

- Balanced Ratio: Often leads to undifferentiated cell growth (callus formation).

Beyond this ratio, hormones exhibit both synergistic (working together to enhance an effect) and antagonistic (opposing each other’s effects) relationships. For instance, gibberellins and auxins often work synergistically to promote stem elongation, while ABA and gibberellins are antagonistic in regulating seed dormancy.

Practical Applications: Harnessing Hormones for Human Benefit

Our understanding of plant hormones has moved beyond mere academic curiosity, leading to numerous practical applications in agriculture, horticulture, and even food storage. By manipulating these powerful compounds, humans can exert significant control over plant growth and development.

- Rooting Cuttings: Synthetic auxins are widely used as “rooting hormones” to stimulate root formation on plant cuttings, enabling easy propagation of desired plant varieties.

- Weed Control: Certain synthetic auxins, when applied in high concentrations, act as potent herbicides. They disrupt the normal growth patterns of broadleaf weeds, causing uncontrolled growth that ultimately leads to their demise, while leaving narrow-leaf crops like corn and wheat relatively unharmed.

- Fruit Production and Storage:

- Gibberellins are sprayed on grapes to increase berry size and loosen clusters, improving air circulation and reducing fungal diseases.

- Ethylene is used to ripen fruits like bananas, tomatoes, and citrus on demand after they have been harvested green for transport. Conversely, ethylene inhibitors are used to delay ripening and extend the shelf life of fruits.

- Auxins can be used to prevent premature fruit drop, ensuring a larger harvest.

- Dwarfism in Ornamentals: Gibberellin inhibitors are used to produce compact, aesthetically pleasing dwarf plants for ornamental purposes, such as poinsettias.

- Breaking Dormancy: Gibberellins can be applied to seeds to break dormancy and promote uniform germination, which is particularly useful in brewing (malting barley).

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

For those with a deeper curiosity, the world of plant hormones extends into fascinating areas of molecular biology and ecological interaction. While the five major hormones form the bedrock of understanding, research continues to uncover new phytohormones and complex signaling pathways.

Signal Transduction and Perception

How does a plant “sense” a hormone? It involves intricate signal transduction pathways. Hormones bind to specific receptor proteins, triggering a cascade of molecular events within the cell that ultimately lead to a physiological response. These pathways often involve secondary messengers and changes in gene expression, allowing for precise and regulated responses.

Hormone Transport

The movement of hormones within the plant is highly regulated. Auxins, for example, exhibit polar transport, moving actively and unidirectionally from the shoot apex downwards. Other hormones, like cytokinins, are primarily transported through the xylem from roots to shoots, while ethylene, being a gas, diffuses through air spaces and cell walls.

Environmental Interactions and Crosstalk

Plant hormones are not just internal regulators; they are also key mediators in a plant’s interaction with its environment. They play crucial roles in responses to:

- Light: Auxins mediate phototropism.

- Gravity: Auxins mediate gravitropism.

- Pathogens and Pests: Hormones like jasmonates and salicylates (often considered “defense hormones”) orchestrate complex defense responses, sometimes even attracting natural enemies of herbivores.

- Nutrient Availability: Hormones help plants optimize root growth to forage for nutrients.

The concept of hormone crosstalk highlights how different hormonal pathways interact and influence each other, creating a sophisticated regulatory network that allows plants to fine-tune their growth and development in response to multiple simultaneous cues.

Conclusion

From the humble seed to the towering tree, plant hormones are the unseen conductors of life’s symphony. They orchestrate every growth spurt, every turn towards the sun, every defense against adversity, and every sweet fruit that graces our tables. Their intricate dance of synthesis, transport, perception, and interaction reveals a level of biological sophistication that rivals any animal system, all without a brain. As we continue to unravel their secrets, our ability to cultivate, protect, and appreciate the plant kingdom only grows, promising a future where we can better harness these natural wonders for a sustainable world.