The natural world is full of fascinating and sometimes unsettling creatures, none perhaps more intriguing than those that have evolved to sustain themselves on the very essence of life: blood. These organisms, collectively known as sanguinivores, represent a diverse group across the animal kingdom, united by their specialized diet. Far from being mere villains in a horror story, sanguinivores play complex and often vital roles within their ecosystems, showcasing some of nature’s most remarkable adaptations.

Beyond the Myths: A Diverse Cast of Blood Feeders

When one thinks of blood-feeding creatures, mosquitoes or vampires often come to mind. However, the reality of sanguinivory is far more varied and extends across multiple phyla. It is a dietary strategy that has independently evolved many times, leading to an astonishing array of forms and behaviors.

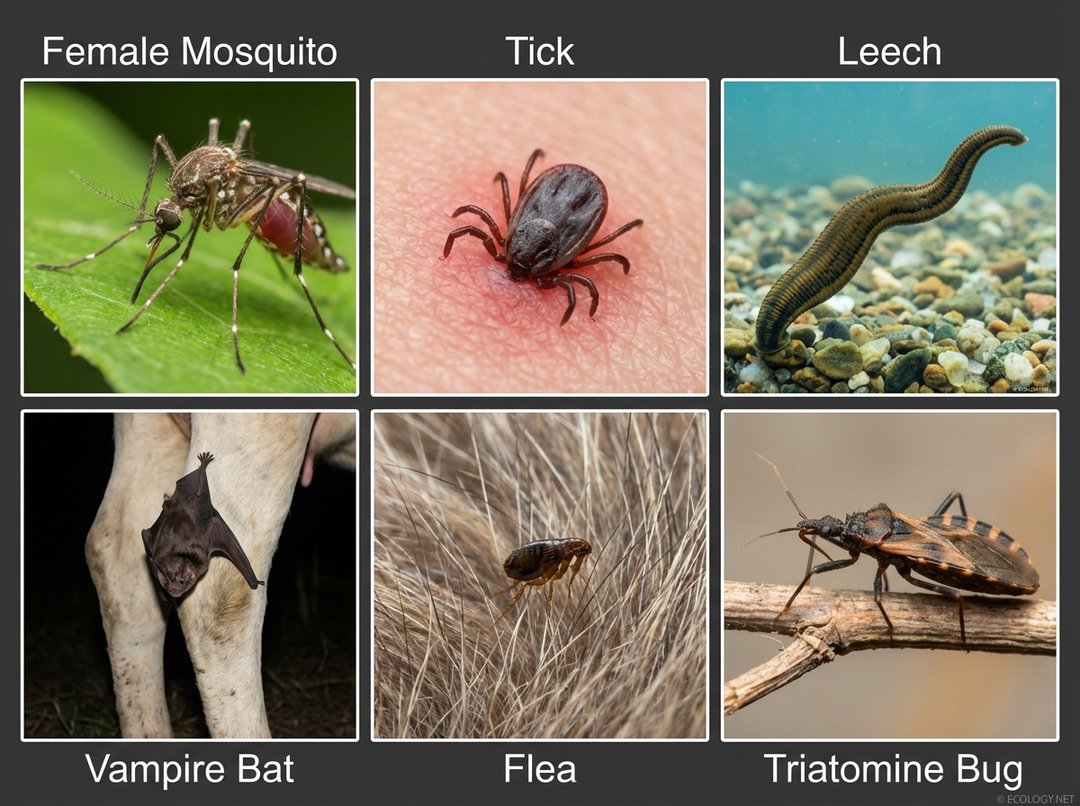

From microscopic parasites to flying mammals, the world of sanguinivores is truly global and encompasses a wide range of life forms. This diverse group includes:

- Insects: Mosquitoes, fleas, lice, bed bugs, and triatomine bugs (often called kissing bugs) are perhaps the most familiar.

- Arachnids: Ticks and mites are notorious blood feeders, often acting as vectors for diseases.

- Annelids: Leeches, with their segmented bodies, are ancient practitioners of sanguinivory, found in aquatic and terrestrial environments.

- Fish: Lampreys, an ancient lineage of jawless fish, are known for attaching to other fish and feeding on their blood.

- Mammals: The vampire bats of Central and South America are the only mammals known to feed exclusively on blood.

Each of these groups has developed unique methods to locate hosts, access blood, and overcome the challenges of this specialized diet.

Adaptations for a Liquid Diet

Sanguinivores face a unique set of challenges. Blood is a nutrient-rich fluid, but it is also protected within a host’s body, can clot rapidly, and is often defended by a robust immune system. To overcome these obstacles, sanguinivores have evolved an impressive suite of biological adaptations.

Specialized Mouthparts

The most obvious adaptation is the development of highly specialized mouthparts designed to pierce skin and access blood vessels. These vary greatly depending on the species:

- Piercing and Sucking Proboscis: Mosquitoes, for example, possess a delicate yet complex proboscis composed of several stylets. Some stylets are serrated to saw through skin, while others form channels for saliva injection and blood uptake.

- Barbed Hypostome: Ticks use a barbed structure called a hypostome to anchor themselves firmly into the host’s skin, allowing for prolonged feeding.

- Suckers and Jaws: Leeches attach with powerful suckers and use three small jaws to make a Y-shaped incision.

- Razor-Sharp Incisors: Vampire bats use their incredibly sharp incisors to make a small, precise incision, often without waking their sleeping prey.

Chemical Warfare: Anticoagulants and Anesthetics

Once a sanguinivore has breached the host’s defenses, it must contend with the blood’s natural clotting mechanisms. To ensure a steady flow, many sanguinivores inject a cocktail of biochemicals into the wound:

- Anticoagulants: These compounds prevent blood from clotting, keeping it liquid for easy consumption. Hirudin from leeches is a well-known example.

- Vasodilators: Some species inject substances that widen blood vessels, increasing blood flow to the feeding site.

- Anesthetics: To avoid detection, many sanguinivores release mild anesthetics that numb the host’s skin, allowing them to feed unnoticed for extended periods.

- Immunomodulators: Certain blood feeders also inject compounds that suppress the host’s immune response, preventing inflammation and facilitating feeding.

Host-Finding Strategies

Locating a suitable host is paramount for survival. Sanguinivores employ a variety of sophisticated sensory mechanisms:

- Chemical Cues: Many insects, like mosquitoes, are highly attuned to carbon dioxide exhaled by hosts, as well as specific body odors and lactic acid.

- Heat Detection: Vampire bats possess specialized heat sensors in their noses that can detect warm blood vessels close to the skin surface. Ticks also respond to body heat.

- Vibrations and Movement: Some species detect vibrations or air currents caused by moving hosts.

- Visual Cues: While less common for initial detection, some sanguinivores may use visual cues to pinpoint a host once they are in close proximity.

The Ecological Roles of Sanguinivores

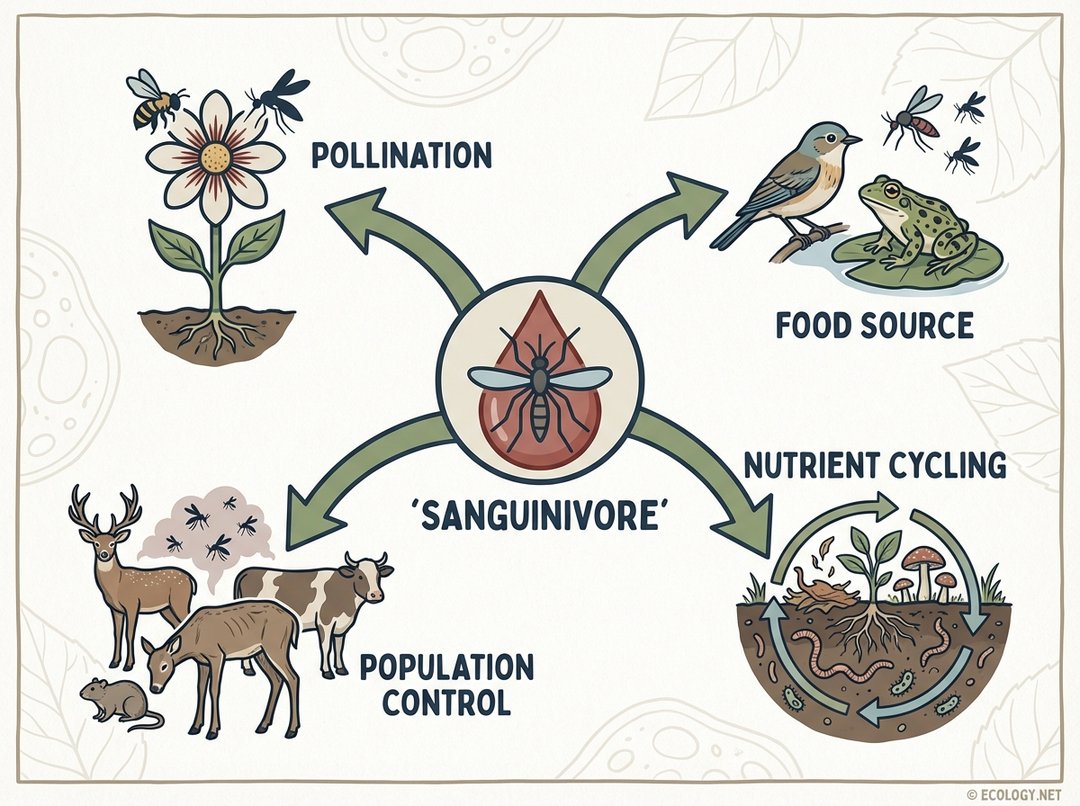

While often perceived solely as pests or disease vectors, sanguinivores are integral components of many ecosystems. Their roles extend far beyond simple parasitism, influencing population dynamics, food webs, and even nutrient cycling.

Food Source for Predators

Despite their often-small size, sanguinivores themselves serve as a crucial food source for a wide array of predators. Mosquitoes, for instance, are a primary food for dragonflies, birds, bats, and fish. Ticks are consumed by certain birds and reptiles. This positions them firmly within the food web, transferring energy from larger hosts to smaller predators.

Population Control

In some cases, heavy infestations of sanguinivores can exert significant pressure on host populations. While rarely the sole factor, chronic blood loss can weaken individuals, making them more susceptible to disease, predation, or environmental stressors. This can contribute to the natural regulation of host animal numbers, preventing overpopulation and maintaining ecosystem balance.

Disease Vectors

Perhaps the most impactful ecological role of many sanguinivores, particularly insects and arachnids, is their capacity to act as vectors for pathogens. Diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, Lyme disease, and Chagas disease are transmitted through the bite of infected blood feeders. This role has profound implications for host health, biodiversity, and even human societies, shaping the distribution and abundance of various species across landscapes.

Unexpected Contributions: Pollination and Nutrient Cycling

While not all sanguinivores directly contribute to these processes, the broader ecological context of some species reveals surprising connections:

- Pollination: Many male mosquitoes, and even some female mosquitoes when not seeking a blood meal, feed on nectar from flowers. In doing so, they inadvertently transfer pollen, contributing to the pollination of various plant species. This highlights that even within a blood-feeding group, dietary habits can vary and include beneficial interactions.

- Nutrient Cycling: The sheer biomass of sanguinivores and their waste products, along with the decomposition of their bodies after death, contribute to the cycling of nutrients within ecosystems. While a less direct role than for decomposers, their presence and life cycles are part of the continuous flow of matter and energy.

Co-evolution and Human Interactions

The relationship between sanguinivores and their hosts is a classic example of co-evolution, an ongoing biological arms race where each side develops new adaptations in response to the other. Hosts evolve better defenses, while sanguinivores develop more sophisticated ways to overcome them. This dynamic interplay drives evolutionary change in both groups.

For humans, understanding sanguinivores is critical for public health and wildlife management. While their ecological roles are undeniable, the transmission of diseases necessitates strategies for control and prevention. However, a holistic ecological perspective emphasizes that management efforts should consider the broader ecosystem impacts, recognizing that even the smallest blood feeder is part of a larger, interconnected web of life.

Conclusion

Sanguinivores, from the buzzing mosquito to the silent tick, are far more than just a nuisance. They are a testament to the incredible adaptability of life, showcasing a specialized dietary strategy that has shaped countless ecosystems. Their intricate adaptations for finding hosts, accessing blood, and evading defenses are marvels of natural selection. By understanding their diverse forms, complex biology, and multifaceted ecological roles, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate balance of nature and our place within it.