Unraveling Forest Stagnation: A Silent Threat to Our Woodlands

Forests are dynamic, living systems, constantly growing, changing, and renewing themselves. We often picture them as timeless havens of green, but beneath the surface, a subtle yet profound process can take hold, transforming vibrant ecosystems into something far less resilient. This process is known as forest stagnation, a condition where a forest’s natural cycle of growth and regeneration grinds to a halt, leaving it vulnerable and diminished.

Understanding forest stagnation is crucial for anyone who cares about the health of our planet. It is not merely a cosmetic issue; it represents a fundamental breakdown in ecological processes, impacting everything from biodiversity to climate regulation. By exploring its causes, characteristics, and solutions, we can better appreciate the intricate balance required for a truly healthy forest.

What Exactly is Forest Stagnation?

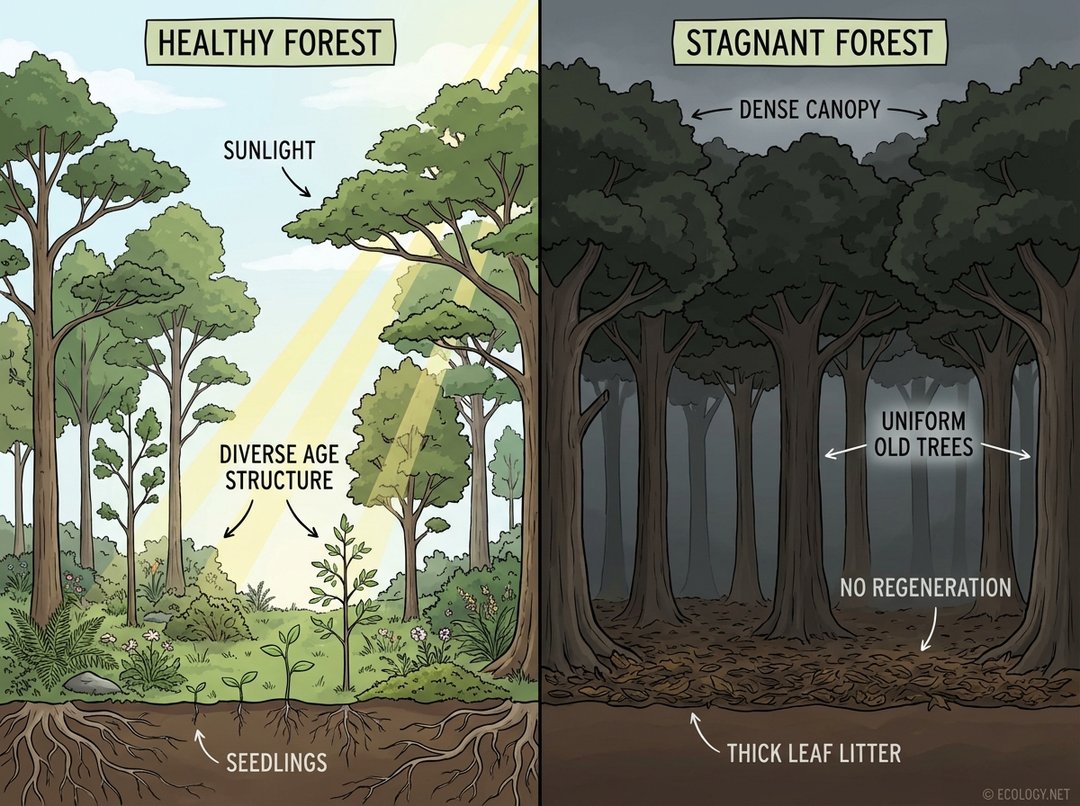

At its core, forest stagnation describes a state where a forest lacks the diversity in age and structure necessary for long-term health and regeneration. Imagine a forest where all the trees are roughly the same age and height, forming a dense, uniform canopy that blocks out most sunlight. The forest floor below is often dark, covered in a thick layer of leaf litter, with very few young seedlings or saplings struggling to grow. This is the hallmark of a stagnant forest.

In contrast, a healthy, thriving forest exhibits a diverse age structure. It is a mosaic of small seedlings, vigorous young trees, and majestic mature giants. Sunlight filters through the canopy, reaching the forest floor and nurturing a rich understory of shrubs, wildflowers, and new tree growth. This continuous cycle of birth, growth, and decay ensures resilience, adaptability, and a vibrant ecosystem.

The visual contrast is striking. A healthy forest buzzes with life at all levels, from the soil to the treetops, while a stagnant forest can feel eerily quiet, a testament to its arrested development.

The Ecological Ripple Effect: Why Stagnation Matters

The consequences of forest stagnation extend far beyond a lack of new trees. When a forest becomes stagnant, its ecological functions are severely compromised:

- Reduced Biodiversity: A uniform forest structure supports fewer species. Many plants and animals rely on specific light conditions, varied habitats, or diverse food sources that are absent in a stagnant environment.

- Increased Susceptibility to Pests and Diseases: Monocultures or stands of similarly aged trees are more vulnerable to widespread outbreaks. If one tree is susceptible, chances are its neighbors are too, allowing pests and diseases to spread rapidly.

- Altered Water Cycles: A dense, uniform canopy can intercept more rainfall, leading to less water reaching the forest floor and streams. The lack of undergrowth can also affect soil moisture retention and nutrient cycling.

- Reduced Carbon Sequestration: While old-growth forests store vast amounts of carbon, a stagnant forest with no new growth or dying trees not being replaced loses its capacity to actively sequester additional carbon, impacting climate regulation.

- Increased Fire Risk: In some ecosystems, the accumulation of dense undergrowth and dead organic matter due to a lack of natural disturbance can create a dangerous fuel ladder, leading to more intense and destructive wildfires.

Unmasking the Causes: How Forests Become Stagnant

Forest stagnation is rarely a natural phenomenon in healthy ecosystems. Instead, it is often a consequence of human activities or the suppression of natural processes. Several key drivers contribute to this ecological decline:

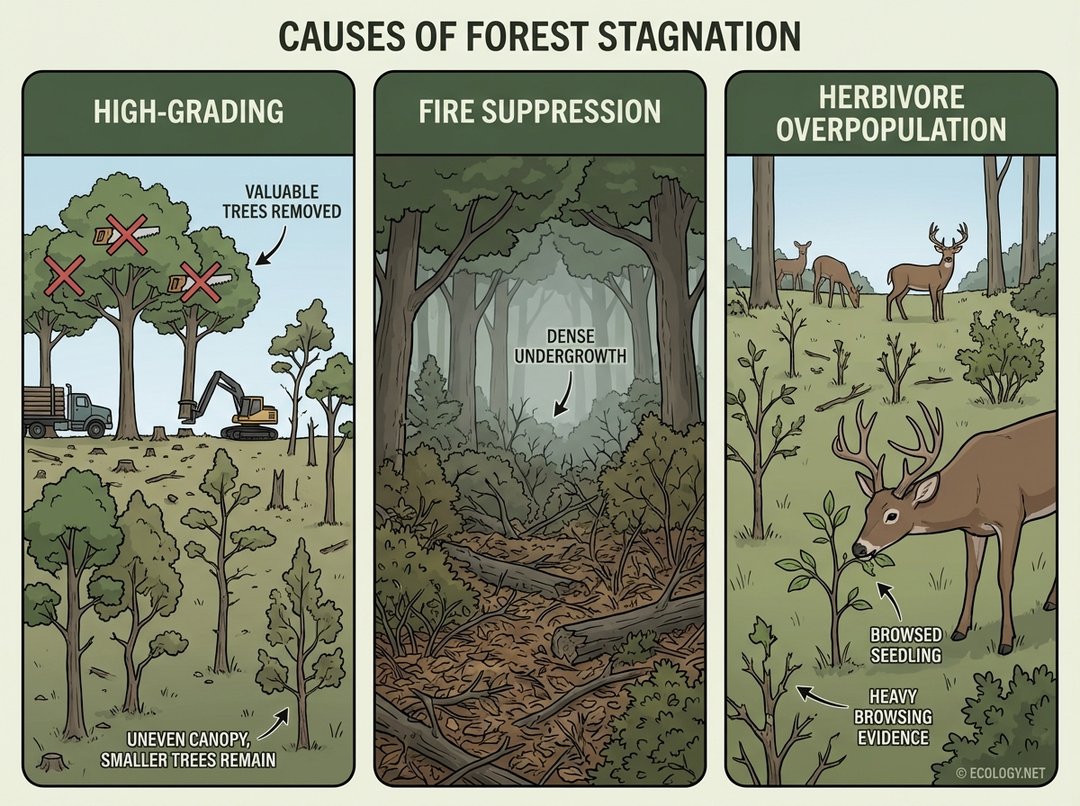

High-Grading: The Selective Removal of the Best

High-grading is a logging practice where only the most valuable, largest, and healthiest trees are harvested, leaving behind smaller, less desirable, or genetically inferior trees. This practice, often driven by short-term economic gains, has devastating long-term effects on forest health. By consistently removing the “best of the best,” the genetic quality of the remaining stand diminishes, and the forest’s capacity to produce strong, resilient offspring is severely hampered. It is akin to continuously breeding from the weakest stock, leading to a decline in the overall vigor of the population.

Fire Suppression: Disrupting Nature’s Cleansing Cycle

For millennia, fire has been a natural and essential component of many forest ecosystems. Low-intensity surface fires would periodically clear out accumulated leaf litter, dead branches, and dense undergrowth, creating space and light for new seedlings to emerge. These fires also released nutrients back into the soil. However, decades of aggressive fire suppression policies have prevented these natural cleansing cycles. The result is an unnatural buildup of fuel on the forest floor, leading to overly dense understories that choke out young growth and, ironically, create conditions for far more catastrophic, high-intensity wildfires when they do occur.

Herbivore Overpopulation: Browsing Away the Future

In many regions, populations of herbivores, such as white-tailed deer, have exploded due to a lack of natural predators and habitat changes. While herbivores are a natural part of the ecosystem, an overabundance can have a profound impact on forest regeneration. Deer, for example, preferentially browse on young seedlings and saplings, especially palatable species. When browsing pressure is too high, it can effectively eliminate an entire generation of young trees, preventing the forest from renewing itself and leading to a uniform, older stand with no future. This phenomenon is often referred to as “deer browse lines” where all vegetation below a certain height is consumed.

Signs of a Stagnant Forest: What to Look For

Identifying a stagnant forest requires a keen eye and an understanding of forest dynamics. Here are some key indicators:

- Uniform Tree Size and Age: Most trees in the stand appear to be of similar height and diameter, indicating they all started growing around the same time.

- Dense, Dark Understory: The forest floor is often dark and barren, with little to no herbaceous growth or young tree seedlings.

- Thick Leaf Litter and Woody Debris: An excessive accumulation of dead leaves, branches, and fallen logs suggests a lack of natural decomposition or disturbance.

- Lack of Regeneration: A noticeable absence of seedlings, saplings, or young trees attempting to grow into the canopy.

- Reduced Wildlife Diversity: Fewer bird species, insects, and other animals that rely on varied habitats may be present.

- Poor Tree Vigor: Individual trees may show signs of stress, such as slow growth, sparse canopies, or increased susceptibility to minor pests.

Breaking the Cycle: Strategies for Forest Restoration

The good news is that forest stagnation is not an irreversible condition. Through thoughtful and proactive forest management, these woodlands can be guided back to health and resilience. Restoration efforts often focus on reintroducing natural processes and creating conditions conducive to regeneration.

Prescribed Burns: Reintroducing Nature’s Fire

Carefully planned and executed prescribed burns are a powerful tool for restoration. By intentionally setting low-intensity fires under controlled conditions, forest managers can mimic natural fire regimes. These burns clear out accumulated fuel, reduce competition from undesirable undergrowth, and release nutrients into the soil. The increased sunlight reaching the forest floor, combined with nutrient-rich ash, creates ideal conditions for new seedlings to sprout and thrive, breaking the cycle of stagnation.

Regenerative Harvesting: Strategic Intervention for Renewal

Unlike high-grading, regenerative harvesting practices are designed to promote forest health and regeneration. Techniques such as variable retention harvesting or group selection involve strategically removing certain trees to create canopy gaps. These gaps allow sunlight to penetrate to the forest floor, stimulating the growth of new seedlings and fostering a diverse age structure. The goal is not just to extract timber, but to actively shape the forest for future health, ensuring a continuous cycle of growth and renewal.

Managing Herbivore Populations: Restoring Ecological Balance

Addressing herbivore overpopulation is critical for successful regeneration. This can involve a combination of strategies, including regulated hunting, predator reintroduction where feasible, or the use of protective measures like fencing for particularly vulnerable areas of new growth. The aim is to bring herbivore populations back into balance with the forest’s capacity to regenerate, allowing young trees to establish themselves without being excessively browsed.

The Path Forward: A Vision for Resilient Forests

Forest stagnation serves as a powerful reminder that our woodlands are not static backdrops, but intricate, living systems that require careful stewardship. By understanding the dynamics of forest health, recognizing the signs of stagnation, and implementing science-based restoration strategies, we can help these vital ecosystems regain their resilience and vitality.

The future of our forests depends on a commitment to active, informed management. It is a long-term endeavor, but the rewards are immense: healthier ecosystems, richer biodiversity, improved climate regulation, and more beautiful, vibrant landscapes for generations to come. By embracing these principles, we can ensure that our forests continue to thrive, providing invaluable benefits to both nature and humanity.